30:

78:

56:

263:, off the coast of Turkey. The remains included a substantial amount of copper oxhide ingot material: 34 in full, five in half, 12 corners, and 75 kilograms (165 lb) of random fragments. Twenty-four full copper oxhide ingots have stamps on their centers—usually of a circle containing intersecting lines. These stamps were likely made when the metal was soft. In addition, the ship contained numerous complete and incomplete copper bun-shaped ingots, rectangular tin bars, and Cypriot agricultural tools made of scrap bronze.

210:

standard and thus the ingots were not a currency. Another theory is that the oxhide shape, as well as the bun shape that some ingots took, was a visual statement that the ingot at hand is part of a legitimate trade. In

Sardinia, oxhide ingot fragments have been found in hoards with bun ingots and scrap metal and, in some cases, in a metallurgical workshop. Citing this evidence, Vasiliki Kassianidou argues that the oxhide ingots "were meant to be used rather than to be kept as prestige goods".

230:

from 20.1 to 29.5 kilograms (44 to 65 lb) after being cleaned of their corrosion. These ingots were found stacked in four rows following a herringbone pattern. The smooth sides of the ingots faced downwards, and the lowest layer rested on brushwood. There are three whole tin oxhide ingots, and there are many tin ingots cut into quarters or halves, with their corner protrusion(s) still intact. Besides metal ingots, the cargo included ivory, metal jewelry, and

369:. Archaeologists found burnt copper droplets around the mold. In spite of the questionable durability of limestone, Paul Craddock et al. concluded that limestone can be used for casting “large simple shapes” such as oxhide ingots. Evolution of carbon dioxide from the limestone would damage the metal surface that touched the mold. Thus, metal objects requiring surface detail could not be produced successfully.

1053:

1058:

229:

In 1982, a diver discovered a shipwreck off the shore of

Uluburun, Turkey. The ship contained 317 copper ingots in the normal oxhide shape, 36 with only two corner protrusions, 121 shaped like buns, and five shaped like pillows. The oxhide ingots (ingots with two or four protrusions) range in weight

336:

Some scholars worry that the 1250 BC date is too limiting. They note that Cyprus was smelting copper on a large scale in the early LBA and had the potential to export the metal to Crete and other places at this time. Furthermore, copper ore is more plentiful on Cyprus than on

Sardinia and far more

394:

While only one oxhide ingot fragment has been recovered from Egypt (in the context of a LBA smelting workshop), there is a wide array of painted scenes in Egypt that show oxhide ingots. The earliest scene dates to the 15th century BC and the latest scene to the 12th century BC. The ingots display

316:

analysis (LIA) suggests that the late LBA ingots (that is, after 1250 BC) are composed of

Cypriot copper, specifically copper from the Apilki mine and its surrounding area. The Gelidonya ingots' ratios are consistent with Cypriot ores while the Uluburun ingots fall on the periphery of the Cypriot

385:

In the Late Bronze Age, Cyprus produced numerous bronze stands that depicted a man carrying an oxhide ingot. The stands were designed to hold vases, and they were cast through the lost-wax process. The ingots show the familiar shape of four protruding handles, and the men carry them over their

242:

of firewood from the ship gives an approximate date of 1300 BC. More than 160 copper oxhide ingots, 62 bun ingots, and some of the tin oxhide ingots have incised marks typically on their rough sides. Some of these marks—resembling fish, oars, and boats—relate to the sea, and they were probably

209:

ingots are similar enough to have allowed "a rough but quick reckoning of a given quantity of raw metal prior to weighing". But George Bass proposes, via the

Gelidonya ingots, whose weights are approximately the same if somewhat lower than the Uluburun ingot weights, that the weights were not

295:

Macroscopic observation of the

Uluburun copper ingots indicates that they were cast through multiple pours; there are distinct layers of metal in each ingot. Furthermore, the relatively high weight and high purity of the ingots would be difficult to achieve even today in only one pour.

246:

Recently Yuval Goren proposed that the ten tons of copper ingots, one ton of tin ingots, and the resin stored in the

Canaanite jars aboard the ship were one complete package. The recipients of the copper, tin, and resin would have used these materials for bronze casting through the

279:

content of less than one weight percent. The few tin oxhide ingots that have been available to study are also exceptionally pure. Microscopic analysis of the

Uluburun copper oxhide ingots reveals that they are highly porous. This feature results from the

189:, approximately 1500 BC to 1450 BC. The latest oxhide ingots date to approximately 1000 BC, and were found on Sardinia. The copper trade was largely maritime: the principal sites where oxhide ingots are found are at sea, on the coast, and on islands.

299:

The porosity of the copper ingots and the natural brittleness of tin suggest that both metal ingots were easy to break. As Bass et al. proposes, a metalsmith could simply break off a piece of the ingot whenever he liked for a new casting.

344:

of tin oxhide ingots and the limited data for lead isotopic studies of tin, the provenance of the tin ingots has been uncertain. The fact that scholars have been unable to pinpoint Bronze Age tin ore deposits compounds this problem.

181:

The appearance of oxhide ingots in the archaeological record corresponds with the beginning of the bulk copper trade in the

Mediterranean—approximately 1600 BC. The earliest oxhide ingots found come from Crete and date to the Late

376:

clay mold, Bass et al. argue that the ingot's smooth side was in contact with the mold while its rough side was exposed to the atmosphere. The roughness results from the interaction of the atmosphere and the cooling metal.

116:

was equivalent to the value of one ox. However, the similarity in shape is simply a coincidence. The ingots' producers probably designed these protrusions to make the ingots easily transportable overland on the backs of

333:. The controversy settles on the validity of LIA. Paul Budd argues that LBA copper is the product of such extensive mixing and recycling that LIA, which works best for metals from a single ore deposit, is unfeasible.

395:

their typical four protrusions, and red paint (which suggests they are copper) is preserved on them. The captions accompanying the scenes explain that the men who bring the ingots come from the north, specifically

809:

Yuval Goren, "International

Exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean: Food and Ships, Sealing-Wax and Kings as Seen Under the Petrographic Microscope," Institute of Archaeology Kenyon Lecture, London, 13 Nov.

564:

Muhly, J. D.; et al. (1988). "Cyprus, Crete, and Sardinia: Copper Oxhide Ingots and the Bronze Age Metals Trade". Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus, Part 1 (Nicosia) (Report).

863:

Stos-Gale, Z. A.; Maliotis, G.; Gale, N. H.; Annetts, N. (1997). "Lead Isotope Characteristics of the Cyprus Copper Ore Deposits Applied to Provenance Studies of Copper Oxhide Ingots".

578:

Stos-Gale, Zofia A.; Gale, Noël H. (1992). "New Light on the Provenience of the Copper Oxhide Ingots Found on Sardinia". In Tykot, Robert H.; Andrews, Tamsey K. (eds.).

426:

to Egypt. Some scholars identify Cyprus with Alashiya. In particular, the Uluburun cargo is similar to the goods that, according to the letters, Alashiya sent to Egypt.

403:(unidentified). They are shown being carried on the shoulders of men, sitting with other goods in storage, or as part of scenes in smelting workshops. In a relief from

634:

Bass, George F.; Throckmorton, Peter; Taylor, Joan Du Plat; Hennessy, J. B.; Shulman, Alan R.; Buchholz, Hans-Günter (1967). "Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck".

767:

Hauptmann, Andreas; Maddin, Robert; Prange, Michael (2002). "On the Structure and Composition of Copper and Tin Ingots Excavated from the Shipwreck of Uluburun".

422:” dating to the mid-14th century BC refer to hundreds of copper talents—in addition to goods such as elephant tusks and glass ingots—sent from the kingdom of

666:

Kassianidou, Vasiliki (2005). "Cypriot Copper in Sardinia: Yet Another Case of Bringing Coals to Newcastle?". In Lo Schiavo, Fulvia; et al. (eds.).

1043:

337:

plentiful than on Crete. Archaeologists have discovered numerous Cypriot exports to Sardinia including metalworking tools and prestige metal objects.

1083:

112:(LBA). Their shape resembles the hide of an ox with a protruding handle in each of the ingot’s four corners. Early thought was that each

386:

shoulders. These Cypriot stands were exported to Crete and Sardinia, and both islands created similar stands in local bronze workshops.

989:

844:

677:

589:

537:

510:

484:

526:

Lo Schiavo, Fulvia (2005). "Oxhide Ingots in the Mediterranean and Central Europe". In Lo Schiavo, Fulvia; et al. (eds.).

66:

1088:

415:

and spearing an oxhide ingot with five arrows. A laudatory caption emphasizing the pharaoh’s strength accompanies the scene.

997:

473:

Pulak, Cemal (2000), "The Copper and Tin Ingots from the Late Bronze Age Shipwreck at Uluburun", in Yalçin, Ünsal (ed.),

502:

Acts of the International Archaeological Symposium "Cyprus between the Orient and the Occident" Nicosia, 8–14 Sept. 1985

84:

29:

202:

44:

1078:

499:

Muhly, J. D. (1986). "The Role of Cyprus in the Economy of the Eastern Mediterranean". In Karageorghis, V. (ed.).

281:

833:

Merkel, John (1986). "Ancient Smelting and Casting of Copper for 'Oxhide' Ingots". In Balmuth, Miriam S. (ed.).

373:

77:

55:

955:

169:. Archaeologists have recovered many oxhide ingots from two shipwrecks off the coast of Turkey (one off

197:

It is uncertain whether the oxhide ingots served as a form of currency. Ingots found in excavations at

1073:

183:

134:

1026:

967:

792:

784:

734:

726:

643:

275:

Typically the copper oxhide ingots are highly pure (approximately 99 weight percent copper) with

264:

224:

206:

170:

840:

673:

585:

533:

506:

480:

354:

288:

inclusions are also present. Their existence implies that slag was not fully removed from the

186:

1059:

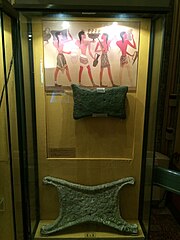

Bronze stand showing oxhide ingot-bearer, found at Kourion, Cyprus, now in the British Museum

1031:

1006:

872:

776:

718:

366:

248:

239:

231:

109:

1047:

876:

419:

260:

372:

This is not to say that oxhide ingots were normally cast in limestone molds. Using an

1067:

971:

796:

738:

276:

106:

709:

Bass, George F. (1986). "A Bronze Age Shipwreck at Ulu Burun (Kaş): 1984 Campaign".

408:

358:

330:

915:, eds. Fulvia Lo Schiavo et al., (Montagnac: Éditions Monique Mergoil, 2005), 313.

834:

579:

527:

500:

474:

322:

158:

130:

118:

309:

1010:

341:

318:

317:

isotopic field. On the other hand, Late Minoan I ingots found on Crete have

839:. Vol. II. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. p. 260.

423:

289:

166:

150:

122:

788:

647:

412:

400:

396:

313:

198:

162:

146:

40:

819:

George F. Bass, "Bronze Age Shipwrecks on the Eastern Mediterranean,"

730:

357:

for casting an oxhide ingot was discovered in the LBA north palace at

404:

235:

142:

138:

98:

62:

902:, trans. Ünsal Yalçin, (Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 2006), 72.

780:

823:, trans. Ünsal Yalçin, (Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 2006), 3.

722:

696:, trans. Ünsal Yalçin, (Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 2006), 6.

667:

362:

154:

126:

113:

36:

267:

of brushwood from the ship gives an approximate date of 1200 BC.

326:

321:

lead isotope ratios and are more consistent with ore sources in

285:

243:

incised after casting, when the ingot was received or exported.

1054:

Oxhide ingot found at Enkomi, Cyprus, now in the British Museum

898:

James D. Muhly, "Copper and Bronze in the Late Bronze Aegean,"

292:

metal and thus that the ingots were made from remelted copper.

259:

In the early 1950s, divers found the remains of a shipwreck in

102:

505:. Nicosia: Department of Antiquities, Cyprus. pp. 55–6.

121:. Complete or partial oxhide ingots have been discovered in

769:

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research

581:

Sardinia in the Mediterranean: A Footprint in the Sea

672:. Montagnac: Éditions Monique Mergoil. p. 336.

532:. Montagnac: Éditions Monique Mergoil. p. 307.

762:

760:

758:

756:

754:

752:

750:

748:

636:Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

97:are heavy (20–30 kg) metal slabs, usually of

988:Karageorghis, Vassos; Papasavvas, George (2001).

479:, Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, p. 138,

983:

981:

858:

856:

629:

627:

625:

623:

621:

559:

557:

555:

553:

551:

549:

468:

466:

464:

462:

460:

458:

205:. Cemal Pulak argues that the weights of the

105:, produced and widely distributed during the

8:

619:

617:

615:

613:

611:

609:

607:

605:

603:

601:

456:

454:

452:

450:

448:

446:

444:

442:

440:

438:

949:

947:

945:

943:

941:

939:

661:

659:

657:

573:

571:

911:Fulvia Lo Schiavo, "Cyprus and Sardinia,"

381:Bronze stands with oxhide ingot depictions

365:. It is made of fine-grained "ramleh", a

16:Mediterranean Late Bronze Age metal slabs

954:Craddock, Paul T.; et al. (1997).

692:Cemal Pulak, "The Uluburun Shipwreck,"

584:. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

434:

704:

702:

284:of gases as the molten metal cooled.

7:

956:"Casting Metals in Limestone Moulds"

201:are now part of the exhibits of the

990:"A Bronze Ingot-bearer from Cyprus"

308:Controversy has swirled around the

877:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1997.tb00792.x

312:of the copper oxhide ingots. Lead

14:

1046:in the shape of an oxhide at the

836:Studies in Sardinian Archaeology

83:Protector of the ingot, bronze,

76:

54:

28:

711:American Journal of Archaeology

67:Heraklion Archaeological Museum

271:Composition and microstructure

1:

1084:Archaeological artefact types

998:Oxford Journal of Archaeology

960:Historical Metallurgy Journal

913:Archaeometallurgy in Sardinia

669:Archaeometallurgy in Sardinia

529:Archaeometallurgy in Sardinia

173:and one in Cape Gelidonya).

203:Numismatic Museum of Athens

45:Numismatic Museum of Athens

1105:

222:

65:, Crete, displayed at the

933:Pulak 2006: 11–12.

255:Cape Gelidonya shipwreck

1011:10.1111/1468-0092.00141

1089:History of metallurgy

900:The Ship of Uluburun

821:The Ship of Uluburun

694:The Ship of Uluburun

390:Egyptian connections

153:capital), Qantir in

43:, displayed at the

35:Copper ingots from

1027:Uluburun shipwreck

265:Radiocarbon dating

249:lost-wax technique

225:Uluburun shipwreck

219:Uluburun shipwreck

61:Copper ingot from

1079:Bronze Age Europe

476:Anatolian Metal I

411:is seen riding a

340:Due to the heavy

101:but sometimes of

1096:

1032:History of money

1015:

1014:

994:

985:

976:

975:

951:

934:

931:

925:

922:

916:

909:

903:

896:

890:

887:

881:

880:

860:

851:

850:

830:

824:

817:

811:

807:

801:

800:

764:

743:

742:

706:

697:

690:

684:

683:

663:

652:

651:

631:

596:

595:

575:

566:

565:

561:

544:

543:

523:

517:

516:

496:

490:

489:

470:

418:Several of the “

367:shelly limestone

240:Tree-ring dating

137:, Cannatello in

80:

58:

32:

1104:

1103:

1099:

1098:

1097:

1095:

1094:

1093:

1064:

1063:

1040:

1023:

1018:

992:

987:

986:

979:

953:

952:

937:

932:

928:

924:Pulak 2006: 12.

923:

919:

910:

906:

897:

893:

888:

884:

862:

861:

854:

847:

832:

831:

827:

818:

814:

808:

804:

781:10.2307/1357777

766:

765:

746:

708:

707:

700:

691:

687:

680:

665:

664:

655:

633:

632:

599:

592:

577:

576:

569:

563:

562:

547:

540:

525:

524:

520:

513:

498:

497:

493:

487:

472:

471:

436:

432:

392:

383:

351:

306:

273:

257:

234:, Cypriot, and

227:

221:

216:

195:

179:

110:Late Bronze Age

92:

91:

90:

89:

88:

81:

72:

71:

70:

59:

50:

49:

48:

33:

24:

23:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1102:

1100:

1092:

1091:

1086:

1081:

1076:

1066:

1065:

1062:

1061:

1056:

1051:

1048:British Museum

1039:

1038:External links

1036:

1035:

1034:

1029:

1022:

1019:

1017:

1016:

1005:(4): 339–354.

977:

935:

926:

917:

904:

891:

889:Pulak 2006: 9.

882:

852:

845:

825:

812:

802:

744:

723:10.2307/505687

717:(3): 269–296.

698:

685:

678:

653:

597:

590:

567:

545:

538:

518:

511:

491:

485:

433:

431:

428:

420:Amarna letters

407:, the pharaoh

391:

388:

382:

379:

350:

347:

305:

302:

272:

269:

261:Cape Gelidonya

256:

253:

223:Main article:

220:

217:

215:

212:

194:

191:

178:

175:

141:, Boğazköy in

82:

75:

74:

73:

60:

53:

52:

51:

34:

27:

26:

25:

21:

20:

19:

18:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1101:

1090:

1087:

1085:

1082:

1080:

1077:

1075:

1072:

1071:

1069:

1060:

1057:

1055:

1052:

1049:

1045:

1042:

1041:

1037:

1033:

1030:

1028:

1025:

1024:

1020:

1012:

1008:

1004:

1000:

999:

991:

984:

982:

978:

973:

969:

965:

961:

957:

950:

948:

946:

944:

942:

940:

936:

930:

927:

921:

918:

914:

908:

905:

901:

895:

892:

886:

883:

878:

874:

870:

866:

859:

857:

853:

848:

846:9780472100811

842:

838:

837:

829:

826:

822:

816:

813:

806:

803:

798:

794:

790:

786:

782:

778:

775:(328): 1–30.

774:

770:

763:

761:

759:

757:

755:

753:

751:

749:

745:

740:

736:

732:

728:

724:

720:

716:

712:

705:

703:

699:

695:

689:

686:

681:

679:9782907303958

675:

671:

670:

662:

660:

658:

654:

649:

645:

641:

637:

630:

628:

626:

624:

622:

620:

618:

616:

614:

612:

610:

608:

606:

604:

602:

598:

593:

591:9781850753865

587:

583:

582:

574:

572:

568:

560:

558:

556:

554:

552:

550:

546:

541:

539:9782907303958

535:

531:

530:

522:

519:

514:

512:9789963364077

508:

504:

503:

495:

492:

488:

486:9783921533796

482:

478:

477:

469:

467:

465:

463:

461:

459:

457:

455:

453:

451:

449:

447:

445:

443:

441:

439:

435:

429:

427:

425:

421:

416:

414:

410:

406:

402:

398:

389:

387:

380:

378:

375:

370:

368:

364:

360:

356:

348:

346:

343:

338:

334:

332:

328:

324:

320:

315:

311:

303:

301:

297:

293:

291:

287:

283:

282:effervescence

278:

277:trace element

270:

268:

266:

262:

254:

252:

250:

244:

241:

237:

233:

226:

218:

213:

211:

208:

204:

200:

192:

190:

188:

185:

176:

174:

172:

168:

164:

160:

156:

152:

148:

144:

140:

136:

132:

128:

124:

120:

115:

111:

108:

107:Mediterranean

104:

100:

96:

95:Oxhide ingots

86:

79:

68:

64:

57:

46:

42:

38:

31:

1044:Copper ingot

1002:

996:

963:

959:

929:

920:

912:

907:

899:

894:

885:

871:: 107, 109.

868:

865:Archaeometry

864:

835:

828:

820:

815:

805:

772:

768:

714:

710:

693:

688:

668:

642:(8): 1–177.

639:

635:

580:

528:

521:

501:

494:

475:

417:

409:Amenhotep II

399:(Syria) and

393:

384:

374:experimental

371:

359:Ras Ibn Hani

352:

339:

335:

331:Central Asia

307:

298:

294:

274:

258:

245:

228:

196:

180:

119:pack animals

94:

93:

323:Afghanistan

214:Major finds

159:Pi-Ramesses

131:Peloponnese

1074:Bronze Age

1068:Categories

430:References

310:provenance

304:Provenance

972:138087661

797:163526572

739:192966981

342:corrosion

319:Paleozoic

238:pottery.

236:Canaanite

232:Mycenaean

157:(ancient

145:(ancient

87:, Cyprus.

1050:website.

1021:See Also

424:Alashiya

207:Uluburun

193:Purposes

171:Uluburun

167:Bulgaria

123:Sardinia

789:1357777

648:1005978

413:chariot

314:isotope

290:smelted

199:Mycenae

177:Context

163:Sozopol

161:), and

151:Hittite

147:Hattusa

41:Mycenae

970:

843:

795:

787:

737:

731:505687

729:

676:

646:

588:

536:

509:

483:

405:Karnak

401:Keftiu

184:Minoan

149:, the

143:Turkey

139:Sicily

135:Cyprus

99:copper

85:Enkomi

63:Zakros

22:Ingots

993:(PDF)

968:S2CID

810:2008.

793:S2CID

785:JSTOR

735:S2CID

727:JSTOR

644:JSTOR

397:Retnu

363:Syria

349:Molds

329:, or

155:Egypt

127:Crete

114:ingot

37:Crete

841:ISBN

674:ISBN

586:ISBN

534:ISBN

507:ISBN

481:ISBN

355:mold

327:Iran

286:Slag

39:and

1007:doi

873:doi

777:doi

773:328

719:doi

361:in

165:in

103:tin

1070::

1003:20

1001:.

995:.

980:^

966:.

964:31

962:.

958:.

938:^

869:39

867:.

855:^

791:.

783:.

771:.

747:^

733:.

725:.

715:90

713:.

701:^

656:^

640:57

638:.

600:^

570:^

548:^

437:^

353:A

325:,

251:.

187:IB

133:,

129:,

125:,

1013:.

1009::

974:.

879:.

875::

849:.

799:.

779::

741:.

721::

682:.

650:.

594:.

542:.

515:.

69:.

47:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.