445:

353:"The most important factor in the loss of Chiriguano independence was the reestablishment of the Franciscan missions" beginning in 1845. After more than two centuries of failure, Christian missions enjoyed some success among the Chiriguanos. The reasons for this success seemed to be that many Chiriguanos turned to the missions for protection from internal disputes and conflict with the Creole ranchers and settlers, the Bolivian government, and other Indian peoples. The missions and the Bolivian government benefited from the labor of the mission Chiriguanos and also recruited many of them as soldiers against independent Chiriguanos and other Indians. The numbers and the independence of the Chiriguano also declined beginning in the 1850s when many of them began migrating to Argentina to work on sugar plantations. By the 1860s, the Bolivian government was taking a more aggressive stand against the Chiriguanos, awarding large grants of land to ranchers in their territory. Outright massacres of Chiriguanos became more common. Chiriguano fighters were routinely executed when captured and women and children sold into servitude.

485:

461:

473:

20:

191:, living mostly at elevations between 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and 2,000 metres (6,600 ft). The climate is sub-tropical and precipitation during the rainy season is adequate for growing crops. The region is characterized by steep ridges and deep river valleys making access and communication difficult. The Chiriguanos were never united as a people into a single political unit, but instead functioned on the village level and formed loosely-organized regional coalitions headed by a paramount chieftain, or

332:

Spanish expeditions into

Chiriguano territory in 1729 and 1731 were less successful. In 1735 the Chiriguano besieged Santa Cruz but the siege was broken by 340 Chiquitano warriors sent from Jesuit missions. In that same year, the Chiriguanos destroyed two reestablished Jesuit missions near Tarija. The Chiriguano integrated some of their captives into their society; others on both sides were released or ransomed, with slavery being a common fate of captives of the Spanish, especially women and children.

115:

350:

Chiriguano maize crops failed during a drought from 1839 to 1841 and the

Chiriguanos resorted to increased raids on cattle herds, both eating the cattle and killing them to halt the advances of the Hispanic ranchers. As the demand for meat increased in the rest of Bolivia, the pressure on the Chiriguanos by the ranchers and soldiers became more intense. Also, it appears that the population of the Chiriguanos declined after the 18th century.

365:(Eunuch of God) and said that he had been sent to earth to save the Chiriguanos from Christianity and the Franciscan missionaries. With an army of 1,300 Chiriguanos, Apiaguaiki led a failed attack against the mission on January 21. The Creoles led a counter-attack on January 28 with 50 soldiers, 140 Creole militia, and 1,500 friendly Indians armed with bows and arrows. In the

444:

279:. By about 1620, however, the Spanish had given up ambitious attempts to advance the frontier. Records are lacking for the next 100 years, but it appears it was a period of relative peace in which Spaniard and indigenous allies enjoyed an uneasy co-existence with the Chiriguanos, although punctuated by mutual raids on each other.

369:, the Creole army killed more than 600 Chiriguanos with losses of their own of only four killed, all Indians. Following the battle, the Creole army massacred Chiriguanos who surrendered and sold women and children into slavery. The 2,000 Chiriguanos resident at the Santa Rosa de Cuevo mission mostly supported the Creole army.

202:

The

Chiriguanos had a warrior ethos, fighting among themselves as well as outsiders. They said they were "men without masters" and considered themselves superior to other peoples whom they called "tapua" or slaves. The Spanish described them in the most unfavorable terms possible: without religion

246:

and surrounding areas. The

Spanish also wished to establish links between their settlements in the Andes and those in Paraguay. In 1564, under a leader named Vitapue, the Chriguanos destroyed two Spanish settlements in eastern Bolivia and a generalized war between the Spaniards and the Chiriguanos

331:

in eastern

Bolivia. The Spanish army destroyed many Chiriguano villages, killed more than 200 people, and took more than 1,000 prisoners. Violating a truce to negotiate an exchange of prisoners, the Spanish captured 62 Chiriguano leaders, including Aruma, and enslaved them in the silver mines.

217:

Until the 19th century the

Chiriguanos proved impervious to the attempts of missionaries to convert them to Christianity. A Jesuit mission in 1767 had only 268 Chiriguano converts, as compared to the tens of thousands the Jesuits had converted eastward in Paraguay among other Guarani speaking

349:

According to scholar Erick Langer, the

Chiriguanos held the upper hand in the Andes borderlands until the 1860s. Spanish-speaking communities, called Creole or "karai" as most of the people were of mixed Spanish/Indian heritage, survived by paying tribute to local Chiriguano groups. However,

335:

After the

General Uprising, additional wars in the 18th century between the Chiriguano and Spanish occurred in 1750 and from 1793 to 1799. The brush-fire wars between Spaniard and Chiriguano were largely conflicts about resources. The Chiriguanos were farmers who grew corn; the Spanish and

251:

led a large—and unsuccessful invasion—into

Chiriguano territory and in 1584 the Spanish declared a "war of fire and blood" against the Chiriguanos. In 1594, the Chiriguano forced the abandonment of the Spanish settlement of Santa Cruz and its relocation to the present site of the city of

174:

Some Ava Guaraní peoples may still have been migrating into the eastern Andes at the time of the

Spanish conquest in the 1530s, possibly drawn by the riches of the Incas and Spanish and in search of the mythical land of "Candire", the "land without evil", rich with gold and other wealth.

226:

Spanish estimates of the number of Chiriguano warriors between 1558 and 1623 range from 500 to 4,000. Despite epidemics of European diseases, the Chiriguano population, probably due in part to the incorporation of the Chané, rose to a high of more than 100,000 in the late 18th century.

306:

at Jesuit and Dominican missions, especially that of Juan Bautista Aruma, who became one of the three principal leaders of the uprising. However, during the war, the Chiriguanos were not united. Their leaders pursued different strategies and some Chiriguanos did not join the uprising.

484:

410:

was attempting to foment revolution among the Chiriguanos when he was captured and executed by Bolivian soldiers on October 9, 1967. Guevara and his Cuban followers had studied Quechua to communicate with Bolivian peasants, but the Chiriguanos spoke

356:

The Chiriguanos made two last attempts to retain their independence: the Huacaya War of 1874-1877, in which rebellious Chiriguanos were defeated, and the rebellion of 1892. The 1892 rebellion broke out in January at the mission of Santa Rosa de

152:" means "cold" in Quechua, the word chirihuano has been interpreted with the pejorative meaning of "people who die from freezing". In the late 16th century, the Quechua term was Hispanized to Chiriguanos. Although Chiriguanos usually refers to

400:(1932-1935) resulted in the dispossession of much of the remaining land belonging to the missions and the Chiriguanos. The Chiriguanos largely became migrant, landless workers, many in Argentina. The missions were finally dissolved in 1949.

318:

peoples, the Chiriguanos attacked with an army of 7,000 men, destroying Christian missions and Spanish ranches east of Tarija, killing more than 200 Spaniards and taking many women and children prisoner. In March 1728, they attacked

340:

settlers encroaching upon or living in Chiriguano territory were ranchers who raised cattle. The ranchers and their cattle destroyed Chiriguano settlements and corn fields and the Chiriguanos killed cattle and often ranchers.

635:

Scholl, Jonathan (2015), "At the Limits of Empire: Incas, Spaniards, and the Ava-Guarani (Chiriguanaes) on the Charca-Chiriguana Frontier, Southeastern Andes (1450s-1620s)", Dissertation, University of Florida, pp. 12,

472:

203:

and government, dedicated to war and cannibalism, naked and sexually promiscuous. That litany of offenses justified, in Spanish eyes, undertaking wars of "fire and blood" against the Chiriguanos and enslaving them.

460:

70:

The Chiriguanos of history nearly disappeared from public consciousness after their 1892 defeat—but were reborn beginning in the 1970s. In the 21st century the descendants of the Chiriguanos call themselves

210:. The Spanish by contrast preferred to fight on horseback and with guns, although guns were in short supply on the frontier for much of history. The Chiriguanos were an agricultural people, cultivating

294:

What historian Thierry Saignes called the "General Uprising" of the Chiriguanos began in 1727. The underlying causes of the uprising were the Spanish colonization of areas near Tarija, led by Jesuit,

415:. In 2005, to attract tourists, the Guarani created the "Trail of Che Guevara" which extends for 300 kilometres (190 mi) through the territory in which Guevara and his mini-army operated.

156:

speaking peoples in eastern Bolivia, the Spanish sometimes applied the term to all Guarani peoples and other lowland people speaking non-Guarani languages living in the eastern Andes and the

263:

The Spanish in the early 17th century followed a policy of attempting to populate the Andean foothills where the Chiriguanos lived and established three main centers as frontier defense:

302:

missionaries and Spanish cattle ranchers who coveted the rich pasture lands of the Andes foothills. The spark that ignited the war was the punishment by the missionaries of Chiriguano

536:

937:

433:

found that 600 Guaraní families in Bolivia continue to live in conditions of "debt bondage and forced labor, which are practices that comprise contemporary forms of slavery."

419:

214:

and other crops. They initially lived in very large longhouses in villages, but, probably for defense, they came to live in small dispersed settlements of individual houses.

422:, founded in 1987, a pan-national organization which represents the Guaraní people in the several countries in which they live. The Guaraní are also represented in the

323:(then called Sauces), burned the Church and took 80 Spanish prisoners. The Spanish counterattacked from Santa Cruz in July 1728 with an army of 1200 Spaniards and 200

396:

in 1930 and asserted that the Chiriguanos had rights as citizens of Bolivia. Cundeye campaigned for the Chiriguanos to reclaim land from the missions. However, the

423:

392:

The influence of the Fransciscan missions declined during the 20th century. A Chiriguano leader named Ubaldino Cundeye, his wife, Octavia, and relatives moved to

90:

The census of 2001 counted 81,011 Guaraní, mostly Chiriguanos, over 15 years of age living in Bolivia. A 2010 census counted 18,000 Ava Guarani in Argentina. The

230:

Large-scale Chiriguano raids against the Inca began in the 1520s. The Inca established defensive settlements, including what are now the archaeological sites of

372:

Apiaguaiki was later captured and on March 29, 1892 was tortured and executed by Bolivian authorities. The movement he led was similar to other contemporary

167:

and migrated southward at an uncertain date. Equally uncertain is the date they arrived in eastern Bolivia. The historical Chirguano were a synthesis of the

171:

and the Guaraní. The Chiroguanos migrated from Paraguay to Bolivia in the beginning of the 16th century absorbing, assimilating, and enslaving the Chané.

163:

The Chiriguanos called themselves "ava," meaning humans. The Guarani people are believed by archaeologists to have originated in the central part of the

19:

430:

1030:

1020:

286:, successful in their missionary enterprises in Paraguay, attempted to Christianize the Chiriguanos as early as the 1630s, but had little success.

1015:

418:

The Eastern Bolivian or Ava Guaraní, as they are increasingly called rather than Chiriguano (which has pejorative origins), participate in the

952:

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, "The Guarani People and the Situation of the Captive Communities in the Bolivian Chaco", pp. 1-2,

522:

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, "The Guarani People and the Situation of the Captive Communities in the Bolivian Chaco", pp. 1-2,

618:

Alconini, Sonia (2004), "The Southeastern Inka Frontier against the Chiriguanos: Structure and Dynamics of the Inka Imperial Borderlands,"

373:

543:

91:

48:

934:

755:. Accessed 23 Sep 2016; Parssinen, Martti, Suriainen, Ari, and Korpisaari, Antti, "Western Amazonia-Amazonia Ocidental", pp. 32. 45-53.

238:, to fend off the Chiriguanos. The Spanish became concerned with the raids of the Chiriguanos in the 1540s because they threatened the

994:

1010:

426:. Their aim is to recover some of their ancestral lands and promote economic development, education, and health among their people.

239:

36:

122:

The common name for the Eastern Bolivian Guaraní since the 16th century has been variations of the name "Chirihuano", a word of

1025:

328:

407:

206:

The Chiriguanos acquired horses and guns from the Spanish, but their preferred method of fighting was on foot and with

537:"Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010: Pueblos Originarios: Región Noroeste Argentino: Serie D N 1"

1035:

118:

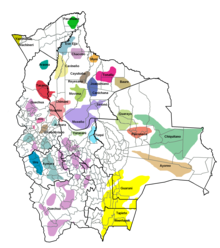

Ethnic groups of Bolivia (2006). The Guarani (Chiriguanos) occupied a larger area in the 16th through 19th century.

51:. Noted for their warlike character, the Chiriguanos retained their lands in the Andes foothills of southeastern

756:

264:

253:

451:

235:

953:

523:

44:

412:

320:

248:

114:

366:

243:

509:

Combés, Isabelle (2005), "Las batallas de Kuruyuki. Variaciones sobre una derrota chiriguana,"

324:

164:

131:

123:

599:

579:

362:

315:

153:

941:

381:

295:

567:

72:

60:

24:

1004:

583:

207:

603:

490:

Interior of Chiriguano hut, Yumbía, Rio Pilcomayo. Photo: E. Nordenskiöld 1913-1914.

650:

257:

890:

377:

311:

75:

which links them with millions of speakers of Guarani dialects and languages in

56:

299:

188:

157:

757:

https://www.academia.edu/7322394/Fortifications_Related_to_the_Inca_Expansion

450:

Chief Mandepora (Mandeponay). In front of him a pot with maizeflour. Photo:

403:

397:

303:

184:

144:

127:

99:

80:

990:

361:. It was led by a 28 year old man named Chapiaguasu, who styled himself

231:

168:

103:

76:

788:

Land without Evil: Utopian Journeys across the South American Watershed

649:, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, pp. 26-34. Downloaded from

337:

283:

95:

64:

52:

183:

The Chiriguanos occupied the foothills between the high Andes and the

752:

393:

276:

268:

84:

954:

http://www.cidh.org/countryrep/ComunidadesCautivas.eng/Chap.Iv.htm

623:

524:

http://www.cidh.org/countryrep/ComunidadesCautivas.eng/Chap.Iv.htm

358:

272:

211:

149:

113:

18:

826:

Gott, pp. 180-182; Saignes, pp 92-94, 220-22; 236; Langer, p. 44

478:

Scene from Chiriguano village. Photo: E. Nordenskiöld 1908-1909.

256:. Some of the settlers abandoned the area and floated down the

126:

origin which referred to itinerant doctors or medicine vendors (

55:

from the 16th to the 19th centuries by fending off, first, the

585:

Contributions towards a grammar and dictionary of Quichua

733:, Lima: Institution Frances de Estudias Andinas, p. 73

647:

Southeast Inka Frontiers: Boundaries and Interactions

466:

Hut and storehouse. Photo: E. Nordenskiöld 1913-1914.

965:

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, pp. 3, 17

751:"Fuerte de Samaipata--UNESCO World Heritage Centre"

729:

Saignes, Thierry, edited by Isabelle Combés (n.d.),

67:. The Chiriguanos were finally subjugated in 1892.

891:http://www.biblioteca.org.ar/libros/153112.pdf

424:Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia

242:(Indian) workers of the rich silver mines at

8:

889:Hurtado Guzman, Emilio, "Apiaguaiqui Tumpa"

684:, Durham: Duke University Press, p. 13, 290

310:In October 1727, with cooperation from the

622:, Vol. 15, No. 4, p. 394. Downloaded from

431:Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

222:Early wars against the Incas and Spanish

511:Bulletin de l'Institut d'Etudes Andines

502:

440:

376:movements around the world such as the

568:Eastern Bolivian Guaraní at Ethnologue

247:began. In 1574, The Viceroy of Peru,

271:, 80 kilometres (50 mi) east of

7:

582:(1864), "Collahuayas, Chirihuanos",

260:to its mouth and returned to Spain.

43:or Chiriguano Indians who speak the

542:(in Spanish). INDEC. Archived from

995:Intercontinental Dictionary Series

753:https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/883

49:Eastern Bolivian Guaraní languages

14:

682:Expecting Pears from an Elm Tree,

92:Eastern Bolivian Guaraní language

513:, Vol 34, No. 2, p. 221, 230-231

483:

471:

459:

443:

63:, and, still later, independent

1031:Santa Cruz Department (Bolivia)

1021:Indigenous peoples in Argentina

437:Pictures by Erland Nordenskiöld

94:was spoken by 33,000 people in

871:Langer, pp. 48-49, 60, 114-117

731:Historia del Pueblo Chiriguano

420:Assembly of the Guaraní People

1:

1016:Indigenous peoples in Bolivia

935:"On the Trail of Che Guevara"

924:, Cooper Square Press, p. 224

902:Langer, pp. 256, 266, 281-282

380:in the United States and the

110:Origin of the name and people

790:, London: Verso, pp. 161-163

429:A 2009 investigation by the

329:Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos

16:Indigenous people in Bolivia

799:Scholl pp. 23, 451, 472-496

327:archers recruited from the

187:and the flat plains of the

1052:

974:Combes, Isabelle (2014),

680:Langer, Erick D. (2009),

605:Travels in Peru and India

1011:Ethnic groups in Bolivia

645:Alconini, Sonia (2016),

620:Latin American Antiquity

662:Alconini (2004), p. 395

388:20th and 21st centuries

265:Santa Cruz de la Sierra

254:Santa Cruz de la Sierra

102:, and a few hundred in

956:, accessed 24 Oct 2016

920:James, Daniel (2001),

893:, accessed 23 Oct 2016

786:Gott, Richard (1993),

759:, accessed 24 Sep 2016

526:, accessed 24 Oct 2016

119:

28:

23:Ava Guaraní people in

1026:Chuquisaca Department

408:Ernesto "Che" Guevara

117:

22:

978:Cochabamba: ILAMIS.

132:province of Larecaja

130:) from the Bolivian

880:Langer, pp. 186-195

768:Scholl, pp. 18, 259

249:Francisco de Toledo

940:2016-10-25 at the

844:Langer, pp. 45--47

817:Saignes, pp. 92-94

693:Scholl, pp. 50, 53

608:, pp. 247–248

588:, pp. 86, 112

367:Battle of Kuruyuki

120:

39:formerly known as

37:Indigenous peoples

29:

1036:Tarija Department

933:Atkinson, David,

853:Langer, pp. 41-47

742:Langer, pp. 15-16

711:Langer, pp. 14-15

702:Scholl, pp. 50-51

165:Amazon rainforest

1043:

979:

972:

966:

963:

957:

950:

944:

931:

925:

918:

912:

909:

903:

900:

894:

887:

881:

878:

872:

869:

863:

860:

854:

851:

845:

842:

836:

833:

827:

824:

818:

815:

809:

806:

800:

797:

791:

784:

778:

775:

769:

766:

760:

749:

743:

740:

734:

727:

721:

718:

712:

709:

703:

700:

694:

691:

685:

678:

672:

669:

663:

660:

654:

643:

637:

633:

627:

616:

610:

609:

600:Clements Markham

596:

590:

589:

580:Clements Markham

576:

570:

565:

559:

558:

556:

554:

548:

541:

533:

527:

520:

514:

507:

487:

475:

463:

447:

363:Apiaguaiki Tumpa

154:Guarani language

1051:

1050:

1046:

1045:

1044:

1042:

1041:

1040:

1001:

1000:

987:

982:

973:

969:

964:

960:

951:

947:

942:Wayback Machine

932:

928:

919:

915:

910:

906:

901:

897:

888:

884:

879:

875:

870:

866:

861:

857:

852:

848:

843:

839:

834:

830:

825:

821:

816:

812:

807:

803:

798:

794:

785:

781:

777:Saignes, p. 193

776:

772:

767:

763:

750:

746:

741:

737:

728:

724:

719:

715:

710:

706:

701:

697:

692:

688:

679:

675:

670:

666:

661:

657:

644:

640:

634:

630:

617:

613:

598:

597:

593:

578:

577:

573:

566:

562:

552:

550:

549:on 9 April 2016

546:

539:

535:

534:

530:

521:

517:

508:

504:

500:

491:

488:

479:

476:

467:

464:

455:

452:E. Nordenskiöld

448:

439:

390:

382:Boxer Rebellion

347:

292:

224:

193:tubicha rubicha

181:

112:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1049:

1047:

1039:

1038:

1033:

1028:

1023:

1018:

1013:

1003:

1002:

999:

998:

986:

985:External links

983:

981:

980:

967:

958:

945:

926:

913:

904:

895:

882:

873:

864:

855:

846:

837:

835:Combés, p. 223

828:

819:

810:

801:

792:

779:

770:

761:

744:

735:

722:

713:

704:

695:

686:

673:

664:

655:

638:

628:

611:

591:

571:

560:

528:

515:

501:

499:

496:

493:

492:

489:

482:

480:

477:

470:

468:

465:

458:

456:

449:

442:

438:

435:

406:revolutionary

389:

386:

346:

343:

291:

288:

223:

220:

197:capitán grande

180:

177:

134:, called also

111:

108:

61:Spanish Empire

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1048:

1037:

1034:

1032:

1029:

1027:

1024:

1022:

1019:

1017:

1014:

1012:

1009:

1008:

1006:

996:

992:

989:

988:

984:

977:

971:

968:

962:

959:

955:

949:

946:

943:

939:

936:

930:

927:

923:

917:

914:

908:

905:

899:

896:

892:

886:

883:

877:

874:

868:

865:

859:

856:

850:

847:

841:

838:

832:

829:

823:

820:

814:

811:

805:

802:

796:

793:

789:

783:

780:

774:

771:

765:

762:

758:

754:

748:

745:

739:

736:

732:

726:

723:

720:Langer, p. 16

717:

714:

708:

705:

699:

696:

690:

687:

683:

677:

674:

668:

665:

659:

656:

652:

648:

642:

639:

632:

629:

625:

621:

615:

612:

607:

606:

601:

595:

592:

587:

586:

581:

575:

572:

569:

564:

561:

545:

538:

532:

529:

525:

519:

516:

512:

506:

503:

497:

495:

486:

481:

474:

469:

462:

457:

453:

446:

441:

436:

434:

432:

427:

425:

421:

416:

414:

409:

405:

401:

399:

395:

387:

385:

383:

379:

375:

370:

368:

364:

360:

354:

351:

344:

342:

339:

333:

330:

326:

322:

317:

313:

308:

305:

301:

297:

289:

287:

285:

280:

278:

274:

270:

266:

261:

259:

255:

250:

245:

241:

237:

233:

228:

221:

219:

215:

213:

209:

208:bow and arrow

204:

200:

199:in Spanish).

198:

194:

190:

186:

178:

176:

172:

170:

166:

161:

159:

155:

151:

147:

146:

141:

137:

133:

129:

125:

116:

109:

107:

105:

101:

97:

93:

88:

86:

82:

78:

74:

68:

66:

62:

59:, later, the

58:

54:

50:

46:

42:

38:

34:

26:

21:

975:

970:

961:

948:

929:

921:

916:

907:

898:

885:

876:

867:

858:

849:

840:

831:

822:

813:

808:Gott, p. 180

804:

795:

787:

782:

773:

764:

747:

738:

730:

725:

716:

707:

698:

689:

681:

676:

671:Google Earth

667:

658:

651:Project MUSE

646:

641:

631:

619:

614:

604:

594:

584:

574:

563:

551:. Retrieved

544:the original

531:

518:

510:

505:

494:

428:

417:

402:

391:

371:

355:

352:

348:

345:19th century

334:

309:

293:

290:18th century

281:

262:

258:Amazon River

229:

225:

216:

205:

201:

196:

192:

182:

173:

162:

143:

139:

135:

121:

98:, 15,000 in

89:

69:

40:

32:

30:

27:, Argentina.

922:Che Guevara

911:Gott, p. xi

378:Ghost Dance

374:Millenarian

148:. Because "

136:Collahuayas

57:Inca Empire

45:Ava Guarani

41:Chiriguanos

33:Ava Guaraní

1005:Categories

991:Chiriguano

862:Langer, 50

553:5 December

498:References

454:1908-1909.

384:in China.

325:Chiquitano

321:Monteagudo

300:Franciscan

240:indigenous

189:Gran Chaco

158:Gran Chaco

145:Charasanis

128:curanderos

976:Kuruyuki,

404:Communist

398:Chaco War

304:neophytes

296:Dominican

236:Samaipata

218:peoples.

185:Altiplano

100:Argentina

81:Argentina

938:Archived

602:(1862),

232:Oroncota

160:region.

140:Yungeños

104:Paraguay

77:Paraguay

73:Guaranis

413:Guarani

338:Mestizo

284:Jesuits

275:), and

179:Culture

124:Quechua

96:Bolivia

65:Bolivia

53:Bolivia

35:are an

394:La Paz

316:Mocoví

298:, and

277:Tarija

269:Tomina

244:Potosí

85:Brazil

83:, and

636:78-85

624:JSTOR

547:(PDF)

540:(PDF)

359:Cuevo

273:Sucre

212:maize

169:Chané

150:chiri

25:Jujuy

555:2015

314:and

312:Toba

282:The

234:and

142:and

47:and

31:The

1007::

267:,

138:,

106:.

87:.

79:,

997:)

993:(

653:.

626:.

557:.

195:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.