335:

430:

347:

mate attraction, although horn size is not positively correlated with territorial factors of mate selection. Their bodies are chestnut brown. The fronts of their faces and their tail tufts are black; the forelimbs and thigh are greyish or bluish-black. Their hindlimbs are brownish-yellow to yellow and their bellies are white. In the wild, tsessebe usually live a maximum of 15 years, but in some areas, their average lifespan is drastically decreased due to overhunting and the destruction of habitat.

80:

31:

55:

449:. Leks are established by the congregation of adult males in an area that females visit only for mating. Lekking is of particular interest since the female choice of a mate in the lek area is independent of any direct male influence. Several options are available to explain how females choose a mate, but the most interesting is in the way the male's group in the middle of a lek.

457:

middle of the lek, it is maintained for quite a while; even if an area opens up at the center, males rarely move to fill it unless they can outcompete the large males already present. However, maintaining central lek territory has many physical drawbacks. For example, males are often wounded in the process of defending their territory from hyenas and other males.

413:

afternoon after 4:00 pm. The periods before and after feeding are spent resting and digesting or watering during dry seasons. Tsessebe can travel up to 5 km to reach a viable water source. To avoid encounters with territorial males or females, tsessebe usually travel along territorial borders, though it leaves them open to attacks by lions and leopards.

422:

629:

industry, began to grow quickly, with large jumps seen in the 2010s. As a large percentage of these animals are found in wild conditions in their natural areas of distribution, this is seen as contributing to the recovery of the species in South Africa. Nonetheless, there are some questions as to the

452:

The grouping of males can appeal to females for several reasons. First, groups of males can protect from predators. Secondly, if males group in an area with a low food supply, it prevents competition between males and females for resources. Finally, the grouping of males provides females with a wider

395:

The most important aggressive display of territorial dominance is in the horning of the ground. Another far more curious form of territory marking is through the anointing of their foreheads and horns with secretions from glands near their eyes. Tsessebe accomplish this by inserting grass stems into

612:

declined significantly, especially in the

National Parks. In 1999 the populations stabilised and began to grow again, especially in private game reserves. There were a number of different theories advanced as to what was causing this decline, while other species were doing well. One 2006 theory for

441:

Tsessebe reproduce at a rate of one calf per year per mating couple. Calves reach sexual maturity in two to three and half years. After mating, the gestation period of a tsessebe cow lasts seven months. The rut, or period when males start competing for females, starts in mid-February and stretches

412:

Tsessebe are primarily grazing herbivores in grasslands, open plains, and lightly wooded savannas, but they are also found in rolling uplands and very rarely in flat plains below 1500 m above sea level. Tsessebe found in the

Serengeti usually feed in the morning between 8:00 and 9:00 am and in the

403:

Several of their behaviors strike scientists as peculiar. One such behavior is the habit of sleeping tsessebe to rest their mouths on the ground with their horns sticking straight up into the air. Male tsessebe has also been observed standing in parallel ranks with their eyes closed, bobbing their

621:

is believed to have played a primary role, with the decline in tsessebe being caused by the proliferation of other antelope species, which was itself due to the opening of man-made watering holes in the game parks. Closing watering holes is believed to increase habitat heterogeneity in the parks,

456:

A study by Bro-Jorgensen (2003) allowed a closer look into lek dynamics. The closer a male is to the center of the lek, the greater his mating success rate. For a male to reach the center of the lek, he must be strong enough to outcompete other males. Once a male's territory is established in the

346:

Adult tsessebe are 150 to 230 cm in length. They are quite large animals, with males weighing 137 kg and females weighing 120 kg, on average. Their horns range from 37 cm for females to 40 cm for males. For males, horn size plays an important role in territory defense and

383:

Tsessebe are social animals. Females form herds composed of six to 10, with their young. After males turn one year of age, they are ejected from the herd and form bachelor herds that can be as large as 30 young bulls. Territorial adult bulls form herds the same size as young bulls, although the

605:, the minimum South African population was estimated as 2,256–2,803 individuals, of which the total minimum mature population size was 1,353–1,962; this was believed to be a significant underestimate, due to not getting enough responses from private game reserves on time for publication.

226:

634:

which are common throughout its range, and with which hybrids have been recorded in both ranches and in

National Parks. Such hybrids are likely fully fertile, and some fear such miscegenation could potentially pollute the gene pool in the future.

374:

are on average the darkest-coloured and have the most robust horns, although differences are slight and individuals in both populations show variation in these characteristics which almost completely overlap each other.

453:

variety of mates to choose from, as they are all located in one central area. Dominant males occupy the center of the leks, so females are more likely to mate at the center than at the periphery of the lek.

400:

to coat them with secretion, then waving it around, letting the secretions fall onto their heads and horns. This process is not as commonly seen as ground-horning, nor is its purpose as well known.

392:

through a variety of behaviors. Territorial behavior includes moving in an erect posture, high-stepping, defecating in a crouch stance, ground-horning, mud packing, shoulder-wiping, and grunting.

354:

is the incline of the horns, with the tsessebe having horns which are placed further apart from each other as one moves distally. This has the effect of the space between them having a more

684:, a type of leather mantle, both for the suppleness and the pleasing colour. The tail would be positioned at the back of the neck, like a ponytail, and would be opened and squeezed flat.

601:

In 1998 the IUCN estimated a total tsessebe population of 30,000, including the

Bangweulu animals. It was assessed as 'lower risk (conservation dependent)'. In the 2016 update to the

1707:

677:

in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, in the some of these countries in game management concessions, in others in game ranches and in some in both.

1578:

1643:

1308:

1767:

1697:

469:, who painted it in "Boosh-wana", and recorded it as the "sassayby". The painting of the animal was first published posthumously in 1820 by his brother.

1552:

1591:

625:

Initially an uncommon animal, in the 2000s the population on private game reserves in both South Africa and

Zimbabwe, primarily stocked for the

1110:

362:. Tsessebe populations show variation as one moves from South Africa to Botswana, with southerly populations having on average the lightest

1046:

404:

heads back and forth. These habits are peculiar because scientists have yet to find a proper explanation for their purposes or functions.

334:

1762:

646:

in particular. A study compared the situation with around Lake Rukwa in

Tanzania in the 1950s, a paper about game populations and the

429:

1026:

903:

865:

1293:

1617:

1348:

497:, by 1895 it was thought that this was the origin for the anglicised word. Other names for the antelope which were recorded by

1635:

1596:

1752:

1742:

1717:

1355:

663:

1732:

1630:

1513:

1207:

743:

1126:

Bro-Jorgensen, Jakob; Sarah M Durant (2003). "Mating

Strategies of Topi Bulls: Getting in the centre of attention".

79:

1747:

1727:

1757:

1737:

1722:

1648:

618:

522:

470:

1712:

1327:

614:

1505:

638:

In northern

Botswana, on the other hand, populations declined from 1996 to 2013, tsessebe populations in the

582:

526:

263:, although some authorities have recognised it as an independent species. It is most closely related to the

1478:

1440:

1378:

1221:

198:

1518:

1669:

215:

1429:

366:

colour, smallest size and the least robust horns. Common tsessebe do not differ significantly from the

1323:

893:

680:

Tsessebe hides were formerly (1840) locally much in demand in South Africa to make a garment called a

1539:

1487:

860:. van den Berg, Philip, van den Berg, Heinrich. Cascades, South Africa: HPH Publishing. p. 102.

434:

339:

489:

for this antelope in

Southern Africa by the end of the 19th century. The English later recorded the

326:

Common tsessebe are among the fastest antelopes in Africa and can run at speeds up to 90 km/h.

1702:

1252:

832:

769:(Bovidae: Alcelaphini) in south-central Africa: with the description of a new evolutionary species"

643:

389:

254:

44:

922:

Bro-Jorgensen, J (2007). "The

Intensity of Sexual Selection Predicts Weapon Size in Male Bovids".

1143:

1069:

947:

651:

367:

351:

350:

The most significant difference between the tsessebe, the southernmost subspecies, and the other

264:

259:

175:

74:

1674:

1583:

1077:

1656:

1526:

1233:

1185:

1106:

1022:

939:

899:

871:

861:

1225:

1177:

1135:

1061:

931:

814:

498:

478:

474:

465:

The first known person in the Western world to record this antelope was the English painter

397:

280:

1661:

1492:

1609:

1167:

578:

490:

1218:

The animal kingdom : arranged in conformity with its organization The class Mammalia

1203:

674:

667:

647:

639:

631:

626:

466:

1691:

1604:

935:

818:

764:

711:

510:

506:

446:

385:

64:

59:

1211:

1171:

1147:

1073:

951:

1531:

1400:

987:

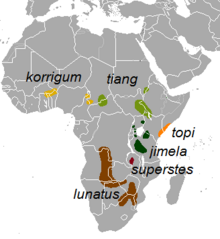

320:

276:

151:

30:

1105:. New York, NY: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 109–112.

358:

profile when seen from a certain angle, as opposed to lyrate, more like that of a

225:

1016:

1622:

1565:

1472:

486:

370:, the northernmost population, but in general the populations from that part of

131:

1065:

574:

482:

442:

through March. The female estrous cycle is shorter, but happens in this time.

359:

161:

1463:

1047:"The Significance of Hotspots to Lekking Topi Antelopes (Damaliscus lunatus)"

875:

702:

1229:

1181:

570:

91:

1237:

1189:

1139:

943:

1349:"17/3/1/1/1 Kimberley Wildlife Sales 2016 –KWS-007-2016 Offer to Purchase"

1457:

609:

542:

534:

316:

312:

308:

288:

272:

111:

1557:

562:

554:

485:

Hills, and renders the name as "sassaybe". Sassaby had thus become the

304:

141:

970:

The Collins Field Guide to the Mammals of African Including Madagascar

421:

1570:

1500:

1021:. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. pp. 142–146.

371:

363:

355:

300:

296:

121:

101:

1434:

384:

formation of adult bull herds is mainly seen in the formation of a

590:

428:

420:

333:

292:

716:

608:

During 1980s and 1990s tsessebe populations in South Africa and

268:

1544:

1438:

917:

915:

670:

under Section 55(2) (b) of the Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003.

1305:

The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho

972:. New York, NY: The Stephen Greene Press, Inc. pp. 81–82.

801:

Dorgeloh, Werner G. (2006). "Habitat Suitability for tsessebe

16:

Subspecies of the subfamily Alcelaphinae in the family Bovidae

603:

Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho

267:, sometimes also seen as a separate species, less to the

1292:

Nel, P.; Schulze, E.; Goodman, P.; Child, M. F. (2016).

1260:

Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission

630:

potential danger of it hybridising with the also native

1251:

East, Rod; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1998).

445:

The breeding process starts with the development of a

963:

961:

796:

794:

701:

IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (7 January 2016).

533:

was the Sekuba name given by the Makuba of northern

1447:

981:

979:

898:. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 428–431.

765:"Insights into the taxonomy of tsessebe antelopes,

573:, indeed it looks somewhat like a cross between a

1176:. Vol. 1. London: R.H. Porter. p. 86.

758:

756:

754:

1224:. London: Geo. B. Whittaker. pp. 352–354.

1161:

1159:

1157:

763:Cotterill, Fenton Peter David (January 2003).

1430:Ultimate Ungulate - Topi (Damaliscus lunatus)

1309:South African National Biodiversity Institute

654:required through their bulldozing behaviour.

477:, was quite familiar with the species in the

8:

1311:and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa.

642:declined by 73%, with a 87% decline in the

1435:

1287:

1285:

1283:

1281:

1040:

1038:

895:The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals

224:

53:

29:

20:

887:

885:

589:to distinguish it from the new Bangweulu

1010:

1008:

1006:

1004:

617:was playing a primary role. As of 2016,

505:in the language of the Masubians of the

1708:Mammals of the Central African Republic

693:

739:

737:

735:

733:

557:. The antelope was recorded as called

1377:Watson, Bruce; Schultz, Dawn (2021).

1018:The Behavior Guide to African Mammals

7:

833:"Tsessebe | Botswana Wildlife Guide"

1768:Taxa named by William John Burchell

1698:IUCN Red List least concern species

1054:Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology

662:Excess tsessebe can be bought from

1220:]. Vol. 4. Translated by

581:'common tsessebe' was invented by

14:

622:which would favour the tsessebe.

936:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00111.x

819:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00654.x

78:

1170:; Wolf, Joseph (January 1895).

295:. Common tsessebe are found in

1294:"A conservation assessment of

1:

856:van den Berg, Ingrid (2015).

1356:South African National Parks

1354:(Press release). Kimberley:

664:South African National Parks

425:Common tsessebes in Botswana

1324:"Okavango Tsessebe Project"

1253:"African Antelope Database"

1784:

1296:Damaliscus lunatus lunatus

807:African Journal of Ecology

803:Damaliscus lunatus lunatus

587:Damaliscus lunatus lunatus

319:(formerly Swaziland), and

250:Damaliscus lunatus lunatus

208:Damaliscus lunatus lunatus

1763:Mammals described in 1824

1328:Wilderness Wildlife Trust

1101:Bateson, Patrick (1985).

1066:10.1007/s00265-002-0573-0

1045:Bro-Jorgensen, J (2003).

892:Kingdon, J (2015-04-23).

673:Legally, tsessebe may be

619:interspecific competition

493:name for the antelope as

473:, in his 1840 book about

471:William Cornwallis Harris

417:Breeding and reproduction

232:

223:

204:

197:

75:Scientific classification

73:

51:

42:

37:

28:

23:

1322:Reeves, Harriet (2018).

1166:Sclater, Philip Lutley;

615:woody plant encroachment

1230:10.5962/bhl.title.45021

1222:Hamilton-Smith, Charles

1182:10.5962/bhl.title.65969

773:Durban Museum Novitates

652:create the open habitat

390:declare their territory

1381:. Bruce Watson Safaris

1140:10.1006/anbe.2003.2077

990:. Kruger National Park

968:Haltenorth, T (1980).

613:this decline was that

501:around this time were

438:

426:

343:

1670:Paleobiology Database

1173:The Book of Antelopes

577:and a horse. The new

432:

424:

337:

38:Tsessebe in Botswana

1753:Fauna of East Africa

1015:Estes, R.D. (1991).

585:in 2005 to refer to

435:Kruger National Park

340:Kruger National Park

338:The close-up at the

1743:Mammals of Tanzania

1718:Mammals of Ethiopia

644:Moremi Game Reserve

597:Conservation status

567:bastaard hartebeest

253:) is the southern,

45:Conservation status

1733:Mammals of Somalia

1506:damaliscus-lunatus

1493:Damaliscus_lunatus

1479:Damaliscus lunatus

1449:Damaliscus lunatus

1401:"Tsessebe hunting"

1379:"Tsessebe Hunting"

837:www.botswana.co.za

767:Damaliscus lunatus

745:Damaliscus lunatus

705:Damaliscus lunatus

439:

427:

368:Bangweulu tsessebe

344:

287:, and less to the

265:Bangweulu tsessebe

260:Damaliscus lunatus

190:D. l. lunatus

1748:Mammals of Uganda

1728:Mammals of Rwanda

1685:

1684:

1657:Open Tree of Life

1441:Taxon identifiers

1112:978-0-521-27207-0

858:Kruger self-drive

398:preorbital glands

237:

236:

68:

1775:

1758:Bovids of Africa

1738:Mammals of Sudan

1723:Mammals of Kenya

1678:

1677:

1665:

1664:

1652:

1651:

1639:

1638:

1626:

1625:

1613:

1612:

1600:

1599:

1587:

1586:

1574:

1573:

1561:

1560:

1548:

1547:

1535:

1534:

1522:

1521:

1509:

1508:

1496:

1495:

1483:

1482:

1481:

1468:

1467:

1466:

1436:

1417:

1416:

1414:

1412:

1397:

1391:

1390:

1388:

1386:

1374:

1368:

1367:

1365:

1363:

1353:

1345:

1339:

1338:

1336:

1334:

1319:

1313:

1312:

1302:

1289:

1276:

1275:

1273:

1271:

1257:

1248:

1242:

1241:

1208:Griffith, Edward

1200:

1194:

1193:

1168:Thomas, Oldfield

1163:

1152:

1151:

1128:Animal Behaviour

1123:

1117:

1116:

1098:

1092:

1091:

1089:

1088:

1082:

1076:. Archived from

1051:

1042:

1033:

1032:

1012:

999:

998:

996:

995:

983:

974:

973:

965:

956:

955:

930:(6): 1316–1326.

919:

910:

909:

889:

880:

879:

853:

847:

846:

844:

843:

829:

823:

822:

798:

789:

788:

786:

784:

760:

749:

741:

728:

727:

725:

723:

698:

648:elephant problem

499:Frederick Selous

479:Cashan Mountains

475:big game hunting

408:Diet and habitat

228:

210:

83:

82:

62:

57:

56:

33:

24:Common tsessebe

21:

1783:

1782:

1778:

1777:

1776:

1774:

1773:

1772:

1713:Mammals of Chad

1688:

1687:

1686:

1681:

1673:

1668:

1660:

1655:

1647:

1642:

1634:

1629:

1621:

1616:

1608:

1603:

1595:

1590:

1582:

1577:

1569:

1564:

1556:

1551:

1543:

1538:

1530:

1525:

1517:

1512:

1504:

1499:

1491:

1486:

1477:

1476:

1471:

1462:

1461:

1456:

1443:

1426:

1421:

1420:

1410:

1408:

1399:

1398:

1394:

1384:

1382:

1376:

1375:

1371:

1361:

1359:

1351:

1347:

1346:

1342:

1332:

1330:

1321:

1320:

1316:

1300:

1291:

1290:

1279:

1269:

1267:

1255:

1250:

1249:

1245:

1204:Cuvier, Georges

1202:

1201:

1197:

1165:

1164:

1155:

1125:

1124:

1120:

1113:

1100:

1099:

1095:

1086:

1084:

1080:

1049:

1044:

1043:

1036:

1029:

1014:

1013:

1002:

993:

991:

985:

984:

977:

967:

966:

959:

921:

920:

913:

906:

891:

890:

883:

868:

855:

854:

850:

841:

839:

831:

830:

826:

800:

799:

792:

782:

780:

762:

761:

752:

742:

731:

721:

719:

700:

699:

695:

690:

660:

599:

579:vernacular name

463:

433:A young at the

419:

410:

381:

352:topi subspecies

332:

241:common tsessebe

233:Range in brown

219:

212:

206:

193:

179:

176:D. lunatus

77:

69:

58:

54:

47:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1781:

1779:

1771:

1770:

1765:

1760:

1755:

1750:

1745:

1740:

1735:

1730:

1725:

1720:

1715:

1710:

1705:

1700:

1690:

1689:

1683:

1682:

1680:

1679:

1666:

1653:

1640:

1627:

1614:

1601:

1588:

1575:

1562:

1549:

1536:

1523:

1510:

1497:

1484:

1469:

1453:

1451:

1445:

1444:

1439:

1433:

1432:

1425:

1424:External links

1422:

1419:

1418:

1405:Book Your Hunt

1392:

1369:

1340:

1314:

1277:

1243:

1195:

1153:

1134:(3): 585–594.

1118:

1111:

1093:

1060:(5): 324–331.

1034:

1027:

1000:

975:

957:

911:

904:

881:

866:

848:

824:

813:(3): 329–336.

790:

750:

729:

692:

691:

689:

686:

659:

656:

650:, which might

640:Okavango Delta

632:red hartebeest

627:trophy hunting

598:

595:

467:Samuel Daniell

462:

459:

437:, South Africa

418:

415:

409:

406:

380:

377:

342:, South Africa

331:

328:

283:subspecies of

257:subspecies of

235:

234:

230:

229:

221:

220:

213:

202:

201:

199:Trinomial name

195:

194:

187:

185:

181:

180:

173:

171:

167:

166:

159:

155:

154:

149:

145:

144:

139:

135:

134:

129:

125:

124:

119:

115:

114:

109:

105:

104:

99:

95:

94:

89:

85:

84:

71:

70:

52:

49:

48:

43:

40:

39:

35:

34:

26:

25:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1780:

1769:

1766:

1764:

1761:

1759:

1756:

1754:

1751:

1749:

1746:

1744:

1741:

1739:

1736:

1734:

1731:

1729:

1726:

1724:

1721:

1719:

1716:

1714:

1711:

1709:

1706:

1704:

1701:

1699:

1696:

1695:

1693:

1676:

1671:

1667:

1663:

1658:

1654:

1650:

1645:

1641:

1637:

1632:

1628:

1624:

1619:

1615:

1611:

1606:

1602:

1598:

1593:

1589:

1585:

1580:

1576:

1572:

1567:

1563:

1559:

1554:

1550:

1546:

1541:

1537:

1533:

1528:

1524:

1520:

1515:

1511:

1507:

1502:

1498:

1494:

1489:

1485:

1480:

1474:

1470:

1465:

1459:

1455:

1454:

1452:

1450:

1446:

1442:

1437:

1431:

1428:

1427:

1423:

1406:

1402:

1396:

1393:

1380:

1373:

1370:

1357:

1350:

1344:

1341:

1329:

1325:

1318:

1315:

1310:

1306:

1299:

1297:

1288:

1286:

1284:

1282:

1278:

1265:

1261:

1254:

1247:

1244:

1239:

1235:

1231:

1227:

1223:

1219:

1215:

1214:

1209:

1205:

1199:

1196:

1191:

1187:

1183:

1179:

1175:

1174:

1169:

1162:

1160:

1158:

1154:

1149:

1145:

1141:

1137:

1133:

1129:

1122:

1119:

1114:

1108:

1104:

1097:

1094:

1083:on 2017-12-12

1079:

1075:

1071:

1067:

1063:

1059:

1055:

1048:

1041:

1039:

1035:

1030:

1028:9780520080850

1024:

1020:

1019:

1011:

1009:

1007:

1005:

1001:

989:

982:

980:

976:

971:

964:

962:

958:

953:

949:

945:

941:

937:

933:

929:

925:

918:

916:

912:

907:

905:9781472921352

901:

897:

896:

888:

886:

882:

877:

873:

869:

867:9780994675125

863:

859:

852:

849:

838:

834:

828:

825:

820:

816:

812:

808:

804:

797:

795:

791:

778:

774:

770:

768:

759:

757:

755:

751:

747:

746:

740:

738:

736:

734:

730:

718:

714:

713:

712:IUCN Red List

708:

706:

697:

694:

687:

685:

683:

678:

676:

675:trophy hunted

671:

669:

668:game auctions

665:

657:

655:

653:

649:

645:

641:

636:

633:

628:

623:

620:

616:

611:

606:

604:

596:

594:

592:

588:

584:

580:

576:

572:

568:

564:

560:

556:

552:

548:

544:

540:

536:

532:

528:

524:

520:

516:

512:

508:

507:Caprivi Strip

504:

500:

496:

492:

488:

484:

480:

476:

472:

468:

460:

458:

454:

450:

448:

443:

436:

431:

423:

416:

414:

407:

405:

401:

399:

393:

391:

387:

378:

376:

373:

369:

365:

361:

357:

353:

348:

341:

336:

329:

327:

324:

322:

318:

314:

310:

306:

302:

298:

294:

290:

286:

282:

278:

274:

270:

266:

262:

261:

256:

252:

251:

246:

242:

231:

227:

222:

217:

211:

209:

203:

200:

196:

192:

191:

186:

183:

182:

178:

177:

172:

169:

168:

165:

164:

160:

157:

156:

153:

150:

147:

146:

143:

140:

137:

136:

133:

130:

127:

126:

123:

120:

117:

116:

113:

110:

107:

106:

103:

100:

97:

96:

93:

90:

87:

86:

81:

76:

72:

66:

61:

60:Least Concern

50:

46:

41:

36:

32:

27:

22:

19:

1448:

1409:. Retrieved

1404:

1395:

1383:. Retrieved

1372:

1360:. Retrieved

1343:

1331:. Retrieved

1317:

1304:

1295:

1268:. Retrieved

1263:

1259:

1246:

1217:

1213:Règne animal

1212:

1198:

1172:

1131:

1127:

1121:

1102:

1096:

1085:. Retrieved

1078:the original

1057:

1053:

1017:

992:. Retrieved

969:

927:

923:

894:

857:

851:

840:. Retrieved

836:

827:

810:

806:

802:

781:. Retrieved

776:

772:

766:

744:

720:. Retrieved

710:

704:

696:

681:

679:

672:

661:

637:

624:

607:

602:

600:

586:

566:

558:

550:

546:

538:

530:

518:

514:

509:(related to

502:

494:

464:

455:

451:

444:

440:

411:

402:

394:

382:

349:

345:

325:

321:South Africa

291:in the same

284:

277:coastal topi

258:

249:

248:

244:

240:

238:

207:

205:

189:

188:

184:Subspecies:

174:

162:

152:Alcelaphinae

132:Artiodactyla

18:

1566:iNaturalist

1473:Wikispecies

1103:Mate Choice

986:Anonymous.

583:Peter Grubb

487:common name

388:. Tsessebe

330:Description

148:Subfamily:

1703:Damaliscus

1692:Categories

1087:2017-12-11

994:2011-11-24

988:"Tsessebe"

842:2017-10-28

688:References

575:hartebeest

571:Afrikaners

523:isiNdebele

483:Kurrichane

360:hartebeest

285:D. lunatus

163:Damaliscus

1266:: 200–207

924:Evolution

876:934195661

519:incomazan

461:Etymology

170:Species:

98:Kingdom:

92:Eukaryota

1636:14200521

1584:10228144

1458:Wikidata

1411:27 April

1385:22 April

1362:24 April

1333:24 April

1270:23 April

1206:(1827).

1148:54229602

1074:52829538

952:24278541

944:17542842

783:18 April

722:23 April

610:Zimbabwe

565:and the

543:Makalaka

535:Botswana

527:Matebele

515:incolomo

495:tsessĕbe

379:Behavior

317:Eswatini

313:Zimbabwe

309:Botswana

289:bontebok

273:korrigum

255:nominate

216:Burchell

138:Family:

122:Mammalia

112:Chordata

108:Phylum:

102:Animalia

88:Domain:

65:IUCN 3.1

1623:1006135

1558:2441041

1464:Q545071

1238:1947779

1210:(ed.).

1190:1236807

779:: 11–30

703:"Topi (

569:by the

563:isiZulu

555:Masaras

553:by the

541:by the

539:inyundo

531:unchuru

521:in the

503:inkweko

305:Namibia

245:sassaby

218:, 1824)

158:Genus:

142:Bovidae

128:Order:

118:Class:

63: (

1675:380406

1597:625082

1545:308534

1519:503076

1501:ARKive

1407:. 2021

1358:. 2016

1236:

1188:

1146:

1109:

1072:

1025:

950:

942:

902:

874:

864:

748:, MSW3

559:myanzi

545:, and

491:Tswana

396:their

372:Zambia

364:pelage

356:lunate

301:Zambia

297:Angola

1662:19010

1579:IRMNG

1571:42276

1532:342XZ

1352:(PDF)

1301:(PDF)

1256:(PDF)

1216:[

1144:S2CID

1081:(PDF)

1070:S2CID

1050:(PDF)

948:S2CID

591:taxon

551:lechu

547:luchu

293:genus

281:tiang

1649:9929

1644:NCBI

1610:6235

1605:IUCN

1592:ITIS

1553:GBIF

1514:BOLD

1413:2021

1387:2021

1364:2021

1335:2021

1272:2021

1234:OCLC

1186:OCLC

1107:ISBN

1023:ISBN

940:PMID

900:ISBN

872:OCLC

862:ISBN

785:2021

724:2021

717:IUCN

682:kobo

666:via

658:Uses

525:of "

517:and

511:Lozi

481:and

279:and

269:topi

239:The

1631:MSW

1618:MDD

1540:EoL

1527:CoL

1488:ADW

1226:doi

1178:doi

1136:doi

1062:doi

932:doi

815:doi

805:".

561:in

549:or

529:",

513:),

447:lek

386:lek

323:.

243:or

1694::

1672::

1659::

1646::

1633::

1620::

1607::

1594::

1581::

1568::

1555::

1542::

1529::

1516::

1503::

1490::

1475::

1460::

1403:.

1326:.

1307:.

1303:.

1280:^

1264:21

1262:.

1258:.

1232:.

1184:.

1156:^

1142:.

1132:65

1130:.

1068:.

1058:53

1056:.

1052:.

1037:^

1003:^

978:^

960:^

946:.

938:.

928:61

926:.

914:^

884:^

870:.

835:.

811:44

809:.

793:^

777:28

775:.

771:.

753:^

732:^

715:.

709:.

707:)"

593:.

537:,

315:,

311:,

307:,

303:,

299:,

275:,

271:,

1415:.

1389:.

1366:.

1337:.

1298:"

1274:.

1240:.

1228::

1192:.

1180::

1150:.

1138::

1115:.

1090:.

1064::

1031:.

997:.

954:.

934::

908:.

878:.

845:.

821:.

817::

787:.

726:.

247:(

214:(

67:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.