1160:) and the ends that they set. All ends that rational agents set have a price and can be exchanged for one another. Ends in themselves, however, have dignity and have no equivalent. In addition to being the basis for the Formula of Autonomy and the kingdom of ends, autonomy itself plays an important role in Kant's moral philosophy. Autonomy is the capacity to be the legislator of the moral law, in other words, to give the moral law to oneself. Autonomy is opposed to heteronomy, which consists of having one's will determined by forces alien to it. Because alien forces could only determine our actions contingently, Kant believes that autonomy is the only basis for a non-contingent moral law. It is in failing to see this distinction that Kant believes his predecessors have failed: their theories have all been heteronomous. At this point Kant has given us a picture of what a universal and necessary law would look like should it exist. However, he has yet to prove that it does exist, or, in other words, that it applies to us. That is the task of Section III.

1129:

such absolute worth, an end in itself, that would be the only possible ground of a categorical imperative. Kant asserts that, “a human being and generally every rational being exists as an end in itself.” The corresponding imperative, the

Formula of Humanity, commands that “you use humanity, whether in your own persona or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.” When we treat others merely as means to our discretionary ends, we violate a perfect duty. However, Kant thinks that we also have an imperfect duty to advance the end of humanity. For example, making a false promise to another person in order to achieve the end of getting some money treats their rational nature as a mere means to one's selfish end. This is, therefore, a violation of a perfect duty. By contrast, it is possible to fail to donate to charity without treating some other person as a mere means to an end, but in doing so we fail to advance the end of humanity, thereby violating an imperfect duty.

1102:

However, Kant thinks that all agents necessarily wish for the help of others from time to time. Therefore, it is impossible for the agent to will that his or her maxim be universally adopted. If an attempt to universalize a maxim results in a contradiction in conception, it violates what Kant calls a perfect duty. If it results in a contradiction in willing, it violates what Kant calls an imperfect duty. Perfect duties are negative duties, that is duties not to commit or engage in certain actions or activities (for example theft). Imperfect duties are positive duties, duties to commit or engage in certain actions or activities (for example, giving to charity).

913:

moral worth. Kant contrasts the shopkeeper with the case of a person who, faced with “adversity and hopeless grief”, and having entirely lost his will to live, yet obeys his duty to preserve his life. Because this person acts from duty, his actions have moral worth. Kant also notes that many individuals possess an inclination to do good; but however commendable such actions may be, they do not have moral worth when they are done out of pleasure. If, however, a philanthropist had lost all capacity to feel pleasure in good works but still did pursue them out of duty, only then would we say they were morally worthy.

1093:. For example, suppose a person in need of money makes it his or her maxim to attain a loan by making a false promise to pay it back. If everyone followed this principle, nobody would trust another person when he or she made a promise, and the institution of promise-making would be destroyed. However, the maxim of making a false promise in order to attain a loan relies on the very institution of promise-making that universalizing this maxim destroys. Kant calls this a "contradiction in conception" because it is impossible to conceive of the maxim being universalized.

1258:

and so too of its laws.” In this sense, the world of understanding is more fundamental than, or ‘grounds’, the world of sense. Because of this, the moral law, which clearly applies to the world of understanding, also applies to the world of sense as well, because the world of understanding has priority. As a result, and because the world of understanding is more fundamental and primary, its laws hold for the world of sense too. The categorical imperative, and therefore the moral law, binds us in the intelligible world and in the phenomenal world of appearances.

1245:. From this perspective, the world may be nothing like the way it appears to human beings. We cannot get out of our heads and leave our human perspective on the world to know what it is like independently of our own viewpoint; we can only know about how the world appears to us, not about how the world is in itself. Kant calls the world as it appears to us from our point of view the world of sense or of appearances. The world from a god's-eye perspective is the world of things in themselves or the “world of understanding.”

1072:), by definition, apply universally. From this observation, Kant derives the categorical imperative, which requires that moral agents act only in a way that the principle of their will could become a universal law. The categorical imperative is a test of proposed maxims; it does not generate a list of duties on its own. The categorical imperative is Kant's general statement of the supreme principle of morality, but Kant goes on to provide three different formulations of this general statement.

1266:

appearance, freedom is impossible. So we are committed to freedom on the one hand, and yet on the other hand we are also committed to a world of appearances that is run by laws of nature and has no room for freedom. We cannot give up on either. We cannot avoid taking ourselves as free when we act, and we cannot give up our picture of the world as determined by laws of nature. As Kant puts it, there is a contradiction between freedom and natural necessity. He calls this a dialectic of reason.

183:

1005:

and principles in order to guide their actions. Thus, only rational creatures have practical reason. The laws and principles that rational agents consult yield imperatives, or rules that necessitate the will. For example, if a person wants to qualify for nationals in ultimate frisbee, he will recognize and consult the rules that tell him how to achieve this goal. These rules will provide him with imperatives that he must follow as long as he wants to qualify for nationals.

1142:

are treating the person with whom you are interacting. The

Formula of Autonomy combines the objectivity of the former with the subjectivity of the latter and suggests that the agent ask what he or she would accept as a universal law. To do this, he or she would test his or her maxims against the moral law that he or she has legislated. The Principle of Autonomy is, “the principle of every human will as a will universally legislating through all its maxims.”

1274:

understanding to explain how freedom is possible or how pure reason could have anything to say about practical matters because we simply do not and cannot have a clear enough grasp of the world of the understanding. The notion of an intelligible world does point us towards the idea of a kingdom of ends, which is a useful and important idea. We just have to be careful not to get carried away and make claims that we are not entitled to.

1822:

122:

3424:

1001:

when it comes to evaluating their motivations for acting, and therefore even in circumstances where individuals believe themselves to be acting from duty, it is possible they are acting merely in accordance with duty and are motivated by some contingent desire. However, the fact that we see ourselves as often falling short of what morality demands of us indicates we have some functional concept of the moral law.

1021:. Hypothetical imperatives provide the rules an agent must follow when he or she adopts a contingent end (an end based on desire or inclination). So, for example, if I want ice cream, I should go to the ice cream shop or make myself some ice cream. However, notice that this imperative only applies if I want ice cream. If I have no interest in ice cream, the imperative does not apply to me.

25:

1232:, Kant, examining phenomena with a philosophical eye, is forced to “admit that no interest impels me to do so.” He says that we clearly do “regard ourselves as free in acting and so to hold ourselves yet subject to certain laws,” but wonders how this is possible. He then explains just how it is possible, by appealing to the two perspectives that we can consider ourselves under.

2193:

1262:

cannot be derived from our phenomenal experience. We can be sure that this concept of freedom doesn't come from experience because experience itself contradicts it. Our experience is of everything in the sensible world and in the sensible world, everything that happens does so in accord with the laws of nature and there is no room for a free will to influence events.

1836:

458:

961:

this law is only binding on the person who wants to qualify for nationals in ultimate frisbee. In this way, it is contingent upon the ends that he sets and the circumstances that he is in. We know from the third proposition, however, that the moral law must bind universally and necessarily, that is, regardless of ends and circumstances.

1249:

understanding that it makes sense to talk of free wills. In the world of appearances, everything is determined by physical laws, and there is no room for a free will to change the course of events. If you consider yourself as part of the world of appearances, then you cannot think of yourself as having a will that brings things about.

1270:

the perspective of the world of the senses or appearances, natural laws determine everything that happens. There is no contradiction because the claim to freedom applies to one world, and the claim of the laws of nature determining everything applies to the other. The claims do not conflict because they have different targets.

565:, followed by three sections. Kant begins from common-sense moral reason and shows by analysis the supreme moral law that must be its principle. He then argues that the supreme moral law in fact obligates us. The book is famously difficult, and it is partly because of this that Kant later, in 1788, decided to publish the

2196:

917:

interpretation asserts that the proposition is that an act has moral worth only if the principle acted upon generates moral action non-contingently. If the shopkeeper in the above example had made his choice contingent upon what would serve the interests of his business, then his act has no moral worth.

1265:

So, Kant argues, we are committed to two incompatible positions. From the perspective of practical reason, which is involved when we consider how to act, we have to take ourselves as free. But from the perspective of speculative reason, which is concerned with investigating the nature of the world of

987:

Later, at the beginning of

Section Two, Kant admits that it is in fact impossible to give a single example of an action that could be certainly said to have been done from duty alone, or ever to know one's own mind well enough to be sure of one's own motives. The important thing, then, is not whether

1257:

On Kant's view, the categorical imperative is possible because, although we as rational agents can be thought of as members of both the intelligible and the phenomenal world (understanding and appearance), it is the intelligible world of understanding that “contains the ground of the world of sense

1227:

thesis, which states that a will is bound by the moral law if and only if it is free. That means that if you know that someone is free, then you know that the moral law applies to them, and vice versa. Kant then asks why we have to follow the principle of morality. Although we all may feel the force

1101:

Second, a maxim might fail by generating what Kant calls a "contradiction in willing." This sort of contradiction comes about when the universalized maxim contradicts something that rational agents necessarily will. For example, a person might have a maxim never to help others when they are in need.

1080:

The first formulation states that an action is only morally permissible if every agent could adopt the same principle of action without generating one of two kinds of contradiction. This is called the

Formula for the Universal Law of Nature, which states that one should, “act as if the maxim of your

1063:

What would the categorical imperative look like? We know that it could never be based on the particular ends that people adopt to give themselves rules of action. Kant believes that this leaves us with one remaining alternative, namely that the categorical imperative must be based on the notion of a

1004:

Kant begins his new argument in

Section II with some observations about rational willing. All things in nature must act according to laws, but only rational beings act in accordance with the representation of a law. In other words, only rational beings have the capacity to recognize and consult laws

960:

Kant believes that all of our actions, whether motivated by inclination or morality, must follow some law. For example, if a person wants to qualify for nationals in ultimate frisbee, he will have to follow a law that tells him to practice his backhand pass, among other things. Notice, however, that

932:

n action from duty has its moral worth not in the purpose to be attained by it but in the maxim in accordance with which it is decided upon, and therefore does not depend upon the realization of the object of the action but merely upon the principle of volition in accordance with which the action is

1269:

The way Kant suggests that we should deal with this dialectic is through an appeal to the two perspectives we can take on ourselves. This is the same sort of move he made earlier in this section. On one perspective, the perspective of the world of understanding, we are free, whereas from the other,

1204:

of freedom: a free will, Kant argues, gives itself a law—it sets its own ends, and has a special causal power to bring them about. A free will is one that has the power to bring about its own actions in a way that is distinct from the way that normal laws of nature cause things to happen. According

1128:

The second formulation of the categorical imperative is the

Formula of Humanity, which Kant arrives at by considering the motivating ground of the categorical imperative. Because the moral law is necessary and universal, its motivating ground must have absolute worth. Were we to find something with

1036:

are determined by the particular ends we set and tell us what is necessary to achieve those particular ends. However, Kant observes that there is one end that we all share, namely our own happiness. Unfortunately, it is difficult, if not impossible, to know exactly what will make us happy or how to

1000:

by criticizing attempts to begin moral evaluation with empirical observation. He states that even when we take ourselves to be behaving morally, we cannot be at all certain that we are purely motivated by duty and not by inclinations. Kant observes that humans are quite good at deceiving themselves

682:

rational reflection. Thus, a correct theoretical understanding of morality requires a metaphysics of morals. Kant believes that, until we have completed this sort of investigation, “morals themselves are liable to all kinds of corruption” because the “guide and supreme norm for correctly estimating

1141:

takes something important from both the

Formula for the Universal Law of Nature and the Formula of Humanity. The Formula for the Universal Law of Nature involves thinking about your maxim as if it were an objective law, while the Formula of Humanity is more subjective and is concerned with how you

945:

Kant combines these two propositions into a third proposition, a complete statement of our common sense notions of duty. This proposition is that ‘duty is necessity of action from respect for law.’ This final proposition serves as the basis of Kant's argument for the supreme principle of morality,

636:

phenomena, like what kind of physical entities there are and the relations in which they stand; the non-empirical part deals with fundamental concepts like space, time, and matter. Similarly, ethics contains an empirical part, which deals with the question of what—given the contingencies of human

912:

who chooses not to overcharge an inexperienced customer. The shopkeeper treats his customer fairly, but because it is in his prudent self-interest to do so, in order to preserve his reputation, we cannot assume that he is motivated by duty, and thus the shopkeeper's action cannot be said to have

1261:

Kant argues that autonomous rational agents, like ourselves, think of themselves as having free will. This permits such beings to make judgments such as “you ought to have done that thing that you did not do.” Kant claims, in both this work and in the first

Critique, that this notion of freedom

1248:

It is the distinction between these two perspectives that Kant appeals to in explaining how freedom is possible. Insofar as we take ourselves to be exercising our free will, Kant argues, we have to consider ourselves from the perspective of the world of understanding. It is only in the world of

1180:

These two different viewpoints allow Kant to make sense of how we can have free wills, despite the fact that the world of appearances follows laws of nature deterministically. Finally, Kant remarks that whilst he would like to be able to explain how morality ends up motivating us, his theory is

1055:

Recall that the moral law, if it exists, must apply universally and necessarily. Therefore, a moral law could never rest on hypothetical imperatives, which only apply if one adopts some particular end. Rather, the imperative associated with the moral law must be a categorical imperative. The

1337:

always already prioritizing the sick, the weakly over the healthy and strong – those capable of valid self-legislation to begin with –, thereby undermining the very possibility of human greatness at its root. But others have stressed many deeper similarities that adherents to a framework of

916:

Scholars disagree about the precise formulation of the first proposition. One interpretation asserts that the missing proposition is that an act has moral worth only when its agent is motivated by respect for the law, as in the case of the man who preserves his life only from duty. Another

1273:

Kant cautions that we cannot feel or intuit this world of the understanding. He also stresses that we are unable to make interesting positive claims about it because we are not able to experience the world of the understanding. Kant argues that we cannot use the notion of the world of the

964:

At this point, Kant asks, "what kind of law can that be, the representation of which must determine the will, even without regard for the effect expected from it...?" He concludes that the only remaining alternative is a law that reflects only the form of law itself, namely that of

1168:

In section three, Kant argues that we have a free will and are thus morally self-legislating. The fact of freedom means that we are bound by the moral law. In the course of his discussion, Kant establishes two viewpoints from which we can consider ourselves; we can view ourselves:

675:

The content and the bindingness of the moral law, in other words, do not vary according to the particularities of agents or their circumstances. Given that the moral law, if it exists, is universal and necessary, the only appropriate means to investigate it is through

855:

is widely taken to be problematic: it is based on the assumption that our faculties have distinct natural purposes for which they are most suitable, and it is questionable whether Kant's critical philosophy could be consistent with this sort of argument.

546:, which states that one must act only according to maxims which one could will to become a universal law. Kant argues that the rightness of an action is determined by the principle that a person chooses to act upon. This stands in stark contrast to the

1240:

According to Kant, human beings cannot know the ultimate structure of reality. Whilst humans experience the world as having three spatial dimensions and as being extended in time, we cannot say anything about how reality ultimately is, from a

1297:

1328:

A nation goes to pieces when it confounds its duty with the general concept of duty. Nothing works a more complete and penetrating disaster than every "impersonal" duty, every sacrifice before the Moloch of abstraction.

795:, but it can be disastrous if a corrupt mind is behind it. In a similar vein, we often desire intelligence and take it to be good, but we certainly would not take the intelligence of an evil genius to be good. The

1208:

Because a free will is not merely pushed around by external forces, external forces do not provide laws for a free will. The only source of law for a free will is that will itself. This is Kant's notion of

1037:

achieve the things that will make us happy. We can only know through experience what certain things will please us and even then, that could change over time. Therefore, Kant argues, we can at best have

3217:

799:, by contrast, is good in itself. Kant writes, “A good will is not good because of what it effects or accomplishes, because of its fitness to attain some proposed end, but only because of its

1120:, Kant suggests that imperfect duties only allow for flexibility in how one chooses to fulfill them. Kant believes that we have perfect and imperfect duties both to ourselves and to others.

920:

Kant states that this is how we should understand the

Scriptural command to love even one's enemy: love as inclination or sentiment cannot be commanded, only rational love as duty can be.

687:

to which human moral reasoning is prone. The search for the supreme principle of morality—the antidote to confusion in the moral sphere—will occupy Kant for the first two chapters of the

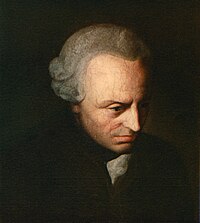

937:

A maxim of an action is its principle of volition. By this, Kant means that the moral worth of an act depends not on its consequences, intended or real, but on the principle acted upon.

265:

1219:

requires that we are morally self-legislating; that we impose the moral law on ourselves. Kant thinks that the positive understanding of freedom amounts to the same thing as the

971:. Thus, Kant arrives at his well-known categorical imperative, the moral law referenced in the above discussion of duty. Kant defines the categorical imperative as the following:

757:’, and ‘moral worth’, will yield the supreme principle of morality (i.e., the categorical imperative). Kant's discussion in section one can be roughly divided into four parts:

908:

Kant thinks our actions only have moral worth and deserve esteem when they are motivated by duty. Kant illustrates the distinction between (b) and (c) with the example of a

1060:

holds for all rational agents, regardless of whatever varying ends a person may have. If we could find it, the categorical imperative would provide us with the moral law.

1205:

to Kant, we need laws to be able to act. An action not based on some sort of law would be arbitrary and not the sort of thing that we could call the result of willing.

610:

is purely formal—it deals only with the form of thought itself, not with any particular objects. Physics and ethics, on the other hand, deal with particular objects:

3458:

through rational means. However, he also further elaborates what this feeling consists in within his other ethical writings. The most notable discussions are in the

811:

Kant believes that a teleological argument may be given to demonstrate that the “true vocation of reason must be to produce a will that is good.” As with other

1598:

Ethical philosophy: the complete texts of

Grounding for the metaphysics of morals, and Metaphysical principles of virtue, part II of The metaphysics of morals

3193:

1189:

Kant opens section III by defining the will as the cause of our actions. According to Kant, having a will is the same thing as being rational, and having a

672:: “That there must be such a philosophy is evident from the common idea of duty and of moral laws.” The moral law must “carry with it absolute necessity.”

1176:

as members of the intellectual world, which is how we view ourselves when we think of ourselves as having free wills and when we think about how to act.

35:

244:

93:

996:

In Section II, Kant starts from scratch and attempts to move from popular moral philosophy to a metaphysics of morals. Kant begins Section II of the

65:

1320:

philosophy, he was quick and unrelenting in his analysis of the inconsistencies throughout Kant's long body of work. Schopenhauer's early admirer,

251:

223:

72:

1181:

unable to do so. This is because the intellectual world—in which morality is grounded—is something that we cannot make positive claims about.

1109:, Kant says that perfect duties never admit of exception for the sake of inclination, which is sometimes taken to imply that imperfect duties

753:. Kant thinks that uncontroversial premises from our shared common-sense morality, and analysis of common sense concepts such as ‘the good’, ‘

1782:

369:

205:

988:

such pure virtue ever actually exists in the world; the important thing is that that reason dictates duty and that we recognize it as such.

819:, Kant's teleological argument is motivated by an appeal to a belief or sense that the whole universe, or parts of it, serve some greater

525:—one that clears the ground for future research by explaining the core concepts and principles of moral theory, and showing that they are

79:

3241:

2223:

735:

is to explain what the moral law would have to be like if it existed and to show that, in fact, it exists and is authoritative for us.

337:

1806:

1081:

action were to become by your will a universal law of nature.” A proposed maxim can fail to meet such requirement in one of two ways.

628:

do not depend on any particular experience for their justification. By contrast, physics and ethics are mixed disciplines, containing

3539:

3529:

2341:

1988:

1963:

1742:

1738:

1711:

1684:

1680:

1651:

1647:

1632:

1628:

1613:

1609:

1590:

1586:

1538:

1472:

1415:

1392:

61:

2253:

888:

Although Kant never explicitly states what the first proposition is, it is clear that its content is suggested by the following

3524:

3519:

1224:

1223:, and that “a free will and a will under moral laws are one and the same.” This is the key notion that later scholars call the

3209:

1640:

Ethical philosophy : the complete texts of grounding for the metaphysics of morals and metaphysical principles of virtue

1563:

833:

or achievement of happiness, which are better served by their natural inclinations. What guides the will in those matters is

50:

581:, motivating the need for pure moral philosophy, Kant makes some preliminary remarks to situate his project and explain his

3026:

2443:

397:

3273:

3233:

3146:

511:

230:

42:

2208:

Modified texts and modern "translations" for easier reading (always consult the original translated source texts first)

2905:

1089:

First, one might encounter a scenario in which one's proposed maxim would become impossible in a world in which it is

699:

In essence, Kant's remarks in the preface prepare the reader for the thrust of the ideas he goes on to develop in the

684:

182:

86:

3544:

3201:

1849:

1798:

1672:

521:. It remains one of the most influential in the field. Kant conceives his investigation as a work of foundational

3392:

1797:

2019. 'Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals', edited and translated by Christopher Bennett, Joe Saunders and

1699:

1115:

966:

620:

517:

407:

326:

258:

3408:

2895:

2552:

2308:

1555:

1284:

712:

633:

589:

214:

1703:

1574:

1453:

1354:

1014:

357:

299:

198:

1621:

Grounding for the metaphysics of morals; with, On a supposed right to lie because of philanthropic concerns

1551:

1300:

is an attempt to prove, among other things, that actions are not moral when they are performed solely from

2885:

2486:

2438:

1481:

1358:

1220:

1057:

1050:

1018:

955:

880:. Kant's argument proceeds by way of three propositions, the last of which is derived from the first two.

841:

791:

or derive their goodness from something else. For example, wealth can be extremely good if it is used for

749:

542:

451:

392:

352:

166:

3534:

3265:

3257:

3185:

3141:

2503:

2498:

2393:

1859:

1730:

1515:

1373:

865:

812:

800:

765:

1427:

803:, that is, it is good in itself.” The precise nature of the good will is subject to scholarly debate.

3382:

3046:

2522:

2512:

2493:

2471:

2433:

2371:

2283:

2246:

1526:

869:

834:

707:

is to prepare a foundation for moral theory. Because Kant believes that any fact that is grounded in

237:

1601:

3352:

3313:

3289:

3156:

3076:

3056:

3031:

3001:

2413:

2293:

1755:

1668:

1442:

1431:

1321:

1289:

708:

551:

412:

374:

304:

1695:

1324:, also criticized the Categorical Imperative as "dangerous to life", in that, among other things:

3347:

3342:

3177:

3116:

2986:

2574:

2481:

2466:

2418:

2366:

1384:

976:

727:) ethics. Such an ethics explains the possibility of a moral law and locates what Kant calls the

678:

629:

547:

1369:

683:

them are missing.” A fully specified account of the moral law will guard against the errors and

903:

the case in which a person's actions coincide with duty because he or she is motivated by duty.

3402:

3387:

3377:

3357:

3106:

2937:

2840:

2830:

2559:

2517:

1984:

1959:

1841:

1802:

1778:

1734:

1707:

1676:

1643:

1624:

1605:

1582:

1559:

1534:

1530:

1511:

1468:

1411:

1388:

1242:

851:, or, in Kant's own words, to “produce a will that is...good in itself.” Kant's argument from

830:

540:

and show that it applies to us. Central to the work is the role of what Kant refers to as the

462:

3372:

3297:

3281:

3111:

3096:

3041:

2820:

2602:

2569:

2564:

2461:

2361:

2298:

2278:

2270:

1794:, two translations (one for scholars, one for students) in multiple formats, by Stephen Orr.

1500:

1090:

816:

526:

900:

the case in which a person's actions coincide with duty, but are not motivated by duty; and

3427:

3161:

2900:

2855:

2815:

2763:

2708:

2698:

2622:

2597:

2579:

2532:

2423:

2356:

2351:

2239:

2218:

2178:

1774:

1726:

1407:

1173:

as members of the world of appearances, which operates according to the laws of nature; or

1151:

476:

435:

363:

347:

316:

1338:

unqualified liberalism, prone to condemning Nietzsche from the canon, have overlooked.

3397:

3151:

3051:

3036:

3011:

3006:

2890:

2780:

2718:

2637:

2627:

2617:

2527:

2408:

2403:

2388:

2328:

2313:

2288:

1770:

1664:

1578:

1489:

1305:

1157:

825:, or end/purpose. If nature's creatures are so purposed, Kant thinks their capacity to

788:

530:

506:

440:

417:

292:

121:

3513:

3081:

3021:

2971:

2810:

2748:

2733:

2632:

2547:

2476:

2428:

2336:

2318:

1722:

980:

792:

638:

625:

502:

321:

274:

174:

132:

1821:

1316:. While he publicly called himself a Kantian, and made clear and bold criticisms of

3362:

3305:

3136:

3131:

3126:

3101:

3071:

2805:

2678:

2612:

2607:

2542:

2398:

2383:

1827:

1197:

of freedom—it tells us that freedom is freedom from determination by alien forces.

889:

876:. That will which is guided by reason, Kant will argue, is the will that acts from

783:

Kant thinks that, with the exception of the good will, all goods are qualified. By

744:

1150:

Kant believes that the Formula of Autonomy yields another “fruitful concept,” the

2214:

3061:

2865:

2642:

2303:

582:

310:

24:

2207:

3121:

3091:

3086:

3066:

3016:

2927:

2785:

2728:

2688:

2683:

2453:

2376:

1854:

1817:

1403:

1309:

1301:

1229:

909:

844:, Kant argues that the capacity to reason must serve another purpose, namely,

668:

Kant proceeds to motivate the need for the special sort of inquiry he calls a

402:

288:

1525:(2nd ed., revised), translated with an introduction by L. W. Beck. New York:

868:, if flawed, still offers that critical distinction between a will guided by

3337:

3249:

2981:

2961:

2860:

2770:

2743:

2723:

2668:

2537:

2346:

1464:

1190:

852:

1312:

and specifically targeted the Categorical Imperative, labeling it cold and

1156:. The kingdom of ends is the “systematic union” of all ends in themselves (

1113:

admit of exception for the sake of inclination. However, in a later work (

3367:

3332:

2966:

2951:

2875:

2870:

2835:

2825:

2738:

2673:

2647:

2202:

1317:

1211:

1193:

means having a will that is not influenced by external forces. This is a

1138:

975:

I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my

537:

342:

1349:

656:. It corresponds to the non-empirical part of physics, which Kant calls

2991:

2880:

2845:

2800:

2795:

2790:

2703:

2693:

1548:

Kant on the foundation of morality; a modern version of the Grundlegung

597:

562:

3492:

719:

reasoning. It is with this significance of necessity in mind that the

2976:

2917:

2850:

2775:

2652:

2262:

1333:

He takes it to be a peculiar expression of "slavish" egalitarianism,

1313:

873:

826:

601:

522:

1497:

Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, and What is Enlightenment?

1486:

The philosophy of Kant; Immanuel Kant's moral and political writings

715:, he can only derive the necessity that the moral law requires from

509:

and the first of his trilogy of major works on ethics alongside the

2186:

1790:

2956:

2946:

1750:

1523:

Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals and What is Enlightenment

821:

747:

morality to the supreme principle of morality, which he calls the

632:

and non-empirical parts. The empirical part of physics deals with

593:

2996:

2912:

2758:

2753:

2713:

1024:

Kant posits that there are two types of hypothetical imperative—

877:

754:

2235:

1623:(3rd ed.), tr. J. W. Ellington. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co.

2922:

933:

done without regard for any object of the faculty of desire.”

554:

that dominated moral philosophy at the time of Kant's career.

18:

1981:

Kant's Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals: A Commentary

1956:

Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals: A Commentary

1461:

The Moral Law: Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals

1450:

The Moral Law; Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals

3218:

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation

2187:

Groundlaying: Kant's Search for the Highest Moral Principle

3446:

For an idea of what Kant means by the feeling of respect (

2231:

897:

the case in which a person clearly acts contrary to duty;

645:

investigation into the nature and substance of morality.

787:, Kant means that those goods are good insofar as they

652:, Kant calls this latter, non-empirical part of ethics

641:, and a non-empirical part, which is concerned with an

536:

Kant proposes to lay bare the fundamental principle of

46:

2198:

The Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals

1424:

The fundamental principles of the metaphysic of ethics

618:

with the laws of freedom. Additionally, logic is an

3325:

3170:

2936:

2661:

2590:

2452:

2327:

2269:

1381:

Fundamental principles of the metaphysics of ethics

1350:

Fundamental principles of the metaphysics of ethics

150:

138:

128:

1642:, tr. J. W. Ellington. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub.

1366:Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals

588:Kant opens the preface with an affirmation of the

1510:, tr. L. W. Beck, with critical essays edited by

1480:1949. "Metaphysical Foundations of Morals," tr.

592:idea of a threefold division of philosophy into

1600:, tr. J. W. Ellington, with an introduction by

1133:The Formula of Autonomy and the Kingdom of Ends

892:observation. Common sense distinguishes among:

1958:. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27.

3454:4:401 where he says that this feeling arises

2247:

1983:. Oxford University Press. pp. 122–126.

1791:Groundlaying toward the Metaphysics of Morals

1402:, tr. T. K. Abbott, edited with revisions by

8:

3194:Fifteen Sermons Preached at the Rolls Chapel

142:

114:

51:introducing citations to additional sources

1445:. London: Hutchinson's University Library.

731:. The aim of the following sections of the

2254:

2240:

2232:

1076:The Formula of the Universal Law of Nature

771:the three propositions regarding duty; and

181:

161:

120:

113:

1777:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1488:, edited by Carl J. Friedrich. New York:

245:Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason

62:"Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals"

1719:Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals

1692:Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals

1508:Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals

1400:Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals

486:Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals

217: Question: What Is Enlightenment?

115:Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

41:Relevant discussion may be found on the

3439:

3226:Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

1871:

1763:Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

1751:Groundwork for the Metaphysic of Morals

1661:Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals

1571:Grounding for the metaphysics of morals

1452:, translated by H. J. Paton. New York:

829:would certainly not serve a purpose of

498:Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

472:Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

173:

1045:Categorical Imperative: Laws of nature

614:is concerned with the laws of nature,

492:Grounding of the Metaphysics of Morals

224:Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals

2074:

2072:

2047:

2045:

2032:

2030:

2017:

2015:

1979:Allison, Henry E. (October 6, 2011).

1954:Timmermann, Jens (December 9, 2010).

1499:, translated with an introduction by

860:The Three Propositions Regarding Duty

815:, such as the case with that for the

481:Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten

266:On a Supposed Right to Tell Lies from

144:Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten

7:

3493:"Nietzsche's Radicalization of Kant"

2002:

2000:

1913:

1911:

1368:, tr. T. K. Abbott, introduction by

950:Categorical Imperative: Universality

16:Philosophical tract by Immanuel Kant

3242:Elements of the Philosophy of Right

2224:Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

1801:. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1292:presents a careful analysis of the

14:

1604:. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co.

1383:, tr. T. K. Abbott. Mineola, NY:

1342:English editions and translations

928:Kant's second proposition states:

743:In section one, Kant argues from

3423:

3422:

2213:Cureton, Adam; Johnson, Robert.

2191:

1834:

1820:

1550:, translated with commentary by

1503:. New York: Liberal Arts Press.

1041:, as opposed to outright rules.

456:

34:relies largely or entirely on a

23:

1754:, edited for easier reading by

3210:The Theory of Moral Sentiments

2580:Value monism – Value pluralism

1236:Gods-eye and human perspective

1200:However, Kant also provides a

723:attempts to establish a pure (

338:Analytic–synthetic distinction

208: Any Future Metaphysics

1:

3491:Sokoloff, William W. (2006).

3476:Nietzsche, Friedrich (1895).

729:supreme principle of morality

3460:Critique of Practical Reason

3274:On the Genealogy of Morality

3234:Critique of Practical Reason

946:the categorical imperative.

567:Critique of Practical Reason

512:Critique of Practical Reason

231:Critique of Practical Reason

2201:public domain audiobook at

1769:, edited and translated by

1463:, tr. H. J. Paton. London:

1310:Kant's philosophical system

1085:Contradiction in conception

774:the categorical imperative.

552:teleological moral theories

3561:

3202:A Treatise of Human Nature

1850:Immanuel Kant bibliography

1702:and Arnulf Zweig. Oxford:

1673:Cambridge University Press

1667:, with an introduction by

1048:

953:

268: Benevolent Motives

3418:

2215:"Kant's Moral Philosophy"

1306:Kant's ethical philosophy

1215:. Thus, Kant's notion of

1116:The Metaphysics of Morals

807:The Teleological Argument

518:The Metaphysics of Morals

507:works on moral philosophy

259:The Metaphysics of Morals

119:

3540:German non-fiction books

3530:Enlightenment philosophy

2553:Universal prescriptivism

1767:A German-English Edition

1556:Indiana University Press

1454:Barnes & Noble Books

1285:On the Basis of Morality

1097:Contradiction in willing

637:nature—tends to promote

3450:), see the footnote in

2342:Artificial intelligence

1704:Oxford University Press

1355:Thomas Kingsmill Abbott

1124:The Formula of Humanity

1013:Imperatives are either

583:method of investigation

358:Hypothetical imperative

300:Transcendental idealism

199:Critique of Pure Reason

3525:Books by Immanuel Kant

3520:1785 non-fiction books

1575:James Wesley Ellington

1359:Longmans, Green and Co

1331:

1304:. Schopenhauer called

1221:categorical imperative

1058:categorical imperative

1051:Categorical imperative

985:

956:Categorical imperative

935:

813:teleological arguments

750:categorical imperative

577:In the preface to the

543:categorical imperative

480:

353:Categorical imperative

143:

3464:Metaphysics of Morals

3266:The Methods of Ethics

2504:Divine command theory

2499:Ideal observer theory

1860:Pure practical reason

1731:Yale University Press

1552:Brendan E. A. Liddell

1326:

1308:the weakest point in

1243:god's-eye perspective

973:

930:

872:and a will guided by

866:teleological argument

842:method of elimination

766:teleological argument

670:metaphysics of morals

664:Metaphysics of morals

658:metaphysics of nature

654:metaphysics of morals

463:Philosophy portal

3462:(5:71–5:76) and the

3383:Political philosophy

1729:, et al. New Haven:

1406:. Peterborough, ON:

1372:. Indianapolis, NY:

1253:Occupying Two Worlds

1039:counsels of prudence

1030:counsels of prudence

548:moral sense theories

483:; also known as the

370:Political philosophy

238:Critique of Judgment

47:improve this article

3353:Evolutionary ethics

3314:Reasons and Persons

3290:A Theory of Justice

2444:Uncertain sentience

1756:Jonathan F. Bennett

1700:Thomas E. Hill, Jr.

1669:Christine Korsgaard

1443:Herbert James Paton

1432:D. Appleton-Century

1322:Friedrich Nietzsche

1290:Arthur Schopenhauer

1217:freedom of the will

1202:positive definition

1195:negative definition

1185:Freedom and Willing

709:empirical knowledge

703:The purpose of the

413:Arthur Schopenhauer

305:Critical philosophy

139:Original title

116:

3348:Ethics in religion

3343:Descriptive ethics

3178:Nicomachean Ethics

1385:Dover Publications

924:Second proposition

624:discipline, i.e.,

501:) is the first of

454: •

291: •

3545:Metaphysics books

3436:

3435:

3403:Social philosophy

3388:Population ethics

3378:Philosophy of law

3358:History of ethics

2841:Political freedom

2518:Euthyphro dilemma

2309:Suffering-focused

1842:Philosophy portal

1783:978-0-521-51457-6

1725:, with essays by

1531:Collier Macmillan

1512:Robert Paul Wolff

1482:Carl J. Friedrich

1428:Otto Manthey-Zorn

1278:Critical reaction

941:Third proposition

884:First proposition

849:produce good will

831:self-preservation

634:contingently true

561:is broken into a

468:

467:

160:

159:

112:

111:

97:

3552:

3505:

3504:

3488:

3482:

3481:

3473:

3467:

3444:

3426:

3425:

3373:Moral psychology

3318:

3310:

3302:

3298:Practical Ethics

3294:

3286:

3282:Principia Ethica

3278:

3270:

3262:

3254:

3246:

3238:

3230:

3222:

3214:

3206:

3198:

3190:

3186:Ethics (Spinoza)

3182:

2821:Moral imperative

2279:Consequentialism

2256:

2249:

2242:

2233:

2228:

2219:Zalta, Edward N.

2195:

2194:

2166:

2160:

2154:

2148:

2142:

2136:

2130:

2124:

2118:

2112:

2106:

2100:

2094:

2088:

2082:

2076:

2067:

2061:

2055:

2049:

2040:

2034:

2025:

2019:

2010:

2004:

1995:

1994:

1976:

1970:

1969:

1951:

1945:

1939:

1933:

1927:

1921:

1915:

1906:

1900:

1894:

1888:

1882:

1876:

1844:

1839:

1838:

1837:

1830:

1825:

1824:

1727:J. B. Schneewind

1663:, translated by

1577:. Indianapolis:

1573:, translated by

1514:. Indianapolis:

1501:Lewis White Beck

1441:, translated by

1426:, translated by

1353:, translated by

979:should become a

817:existence of God

461:

460:

459:

267:

216:

207:

185:

162:

152:Publication date

146:

124:

117:

107:

104:

98:

96:

55:

27:

19:

3560:

3559:

3555:

3554:

3553:

3551:

3550:

3549:

3510:

3509:

3508:

3490:

3489:

3485:

3480:. pp. §11.

3475:

3474:

3470:

3445:

3441:

3437:

3432:

3414:

3321:

3316:

3308:

3300:

3292:

3284:

3276:

3268:

3260:

3252:

3244:

3236:

3228:

3220:

3212:

3204:

3196:

3188:

3180:

3166:

2939:

2932:

2856:Self-discipline

2816:Moral hierarchy

2764:Problem of evil

2709:Double standard

2699:Culture of life

2657:

2586:

2533:Non-cognitivism

2448:

2323:

2265:

2260:

2212:

2192:

2175:

2170:

2169:

2161:

2157:

2149:

2145:

2137:

2133:

2125:

2121:

2113:

2109:

2101:

2097:

2089:

2085:

2077:

2070:

2062:

2058:

2050:

2043:

2035:

2028:

2020:

2013:

2005:

1998:

1991:

1978:

1977:

1973:

1966:

1953:

1952:

1948:

1940:

1936:

1928:

1924:

1916:

1909:

1901:

1897:

1889:

1885:

1877:

1873:

1868:

1840:

1835:

1833:

1826:

1819:

1816:

1775:Jens Timmermann

1579:Hackett Pub. Co

1554:. Bloomington:

1408:Broadview Press

1344:

1280:

1255:

1238:

1187:

1166:

1158:rational agents

1153:kingdom of ends

1148:

1146:Kingdom of ends

1137:The Formula of

1135:

1126:

1099:

1087:

1078:

1053:

1047:

1011:

994:

958:

952:

943:

926:

906:

886:

862:

809:

781:

741:

697:

685:rationalization

666:

575:

531:rational agents

457:

455:

446:

445:

436:German idealism

431:

423:

422:

388:

380:

379:

364:Kingdom of Ends

317:Thing-in-itself

295:

281:

280:

252:Perpetual Peace

193:

153:

108:

102:

99:

56:

54:

40:

28:

17:

12:

11:

5:

3558:

3556:

3548:

3547:

3542:

3537:

3532:

3527:

3522:

3512:

3511:

3507:

3506:

3483:

3478:The Antichrist

3468:

3438:

3434:

3433:

3431:

3430:

3419:

3416:

3415:

3413:

3412:

3405:

3400:

3398:Secular ethics

3395:

3393:Rehabilitation

3390:

3385:

3380:

3375:

3370:

3365:

3360:

3355:

3350:

3345:

3340:

3335:

3329:

3327:

3323:

3322:

3320:

3319:

3311:

3303:

3295:

3287:

3279:

3271:

3263:

3258:Utilitarianism

3255:

3247:

3239:

3231:

3223:

3215:

3207:

3199:

3191:

3183:

3174:

3172:

3168:

3167:

3165:

3164:

3159:

3154:

3149:

3144:

3139:

3134:

3129:

3124:

3119:

3114:

3109:

3104:

3099:

3094:

3089:

3084:

3079:

3074:

3069:

3064:

3059:

3054:

3049:

3044:

3039:

3034:

3029:

3024:

3019:

3014:

3009:

3004:

2999:

2994:

2989:

2984:

2979:

2974:

2969:

2964:

2959:

2954:

2949:

2943:

2941:

2934:

2933:

2931:

2930:

2925:

2920:

2915:

2910:

2909:

2908:

2903:

2898:

2888:

2883:

2878:

2873:

2868:

2863:

2858:

2853:

2848:

2843:

2838:

2833:

2828:

2823:

2818:

2813:

2808:

2803:

2798:

2793:

2788:

2783:

2778:

2773:

2768:

2767:

2766:

2761:

2756:

2746:

2741:

2736:

2731:

2726:

2721:

2716:

2711:

2706:

2701:

2696:

2691:

2686:

2681:

2676:

2671:

2665:

2663:

2659:

2658:

2656:

2655:

2650:

2645:

2640:

2635:

2630:

2625:

2620:

2618:Existentialist

2615:

2610:

2605:

2600:

2594:

2592:

2588:

2587:

2585:

2584:

2583:

2582:

2572:

2567:

2562:

2557:

2556:

2555:

2550:

2545:

2540:

2530:

2525:

2520:

2515:

2513:Constructivism

2510:

2509:

2508:

2507:

2506:

2501:

2491:

2490:

2489:

2487:Non-naturalism

2484:

2469:

2464:

2458:

2456:

2450:

2449:

2447:

2446:

2441:

2436:

2431:

2426:

2421:

2416:

2411:

2406:

2401:

2396:

2391:

2386:

2381:

2380:

2379:

2369:

2364:

2359:

2354:

2349:

2344:

2339:

2333:

2331:

2325:

2324:

2322:

2321:

2316:

2314:Utilitarianism

2311:

2306:

2301:

2296:

2291:

2286:

2281:

2275:

2273:

2267:

2266:

2261:

2259:

2258:

2251:

2244:

2236:

2230:

2229:

2210:

2205:

2189:

2184:

2174:

2173:External links

2171:

2168:

2167:

2155:

2143:

2131:

2119:

2107:

2095:

2083:

2068:

2056:

2041:

2026:

2011:

1996:

1989:

1971:

1964:

1946:

1934:

1922:

1907:

1895:

1883:

1870:

1869:

1867:

1864:

1863:

1862:

1857:

1852:

1846:

1845:

1831:

1815:

1812:

1811:

1810:

1807:978-0198786191

1795:

1786:

1759:

1746:

1715:

1688:

1665:Mary J. Gregor

1657:

1656:

1655:

1636:

1617:

1602:Warner A. Wick

1567:

1544:

1543:

1542:

1519:

1493:

1490:Modern Library

1478:

1477:

1476:

1457:

1435:

1420:

1419:

1418:

1396:

1377:

1343:

1340:

1279:

1276:

1254:

1251:

1237:

1234:

1186:

1183:

1178:

1177:

1174:

1165:

1162:

1147:

1144:

1134:

1131:

1125:

1122:

1098:

1095:

1086:

1083:

1077:

1074:

1049:Main article:

1046:

1043:

1034:Rules of skill

1026:rules of skill

1010:

1007:

993:

990:

954:Main article:

951:

948:

942:

939:

925:

922:

905:

904:

901:

898:

894:

885:

882:

861:

858:

808:

805:

780:

777:

776:

775:

772:

769:

762:

761:the good will;

740:

737:

696:

693:

665:

662:

648:Because it is

626:logical truths

574:

571:

466:

465:

448:

447:

444:

443:

441:Neo-Kantianism

438:

432:

430:Related topics

429:

428:

425:

424:

421:

420:

418:Baruch Spinoza

415:

410:

405:

400:

398:G. W. F. Hegel

395:

389:

386:

385:

382:

381:

378:

377:

372:

367:

360:

355:

350:

345:

340:

335:

324:

319:

314:

307:

302:

296:

293:Kantian ethics

287:

286:

283:

282:

279:

278:

271:

262:

255:

248:

241:

234:

227:

220:

211:

206:Prolegomena to

202:

194:

191:

190:

187:

186:

178:

177:

171:

170:

158:

157:

154:

151:

148:

147:

140:

136:

135:

130:

126:

125:

110:

109:

45:. Please help

31:

29:

22:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

3557:

3546:

3543:

3541:

3538:

3536:

3533:

3531:

3528:

3526:

3523:

3521:

3518:

3517:

3515:

3503:(4): 501–518.

3502:

3498:

3494:

3487:

3484:

3479:

3472:

3469:

3466:(6:399–6:418)

3465:

3461:

3457:

3453:

3449:

3443:

3440:

3429:

3421:

3420:

3417:

3411:

3410:

3406:

3404:

3401:

3399:

3396:

3394:

3391:

3389:

3386:

3384:

3381:

3379:

3376:

3374:

3371:

3369:

3366:

3364:

3361:

3359:

3356:

3354:

3351:

3349:

3346:

3344:

3341:

3339:

3336:

3334:

3331:

3330:

3328:

3324:

3315:

3312:

3307:

3304:

3299:

3296:

3291:

3288:

3283:

3280:

3275:

3272:

3267:

3264:

3259:

3256:

3251:

3248:

3243:

3240:

3235:

3232:

3227:

3224:

3219:

3216:

3211:

3208:

3203:

3200:

3195:

3192:

3187:

3184:

3179:

3176:

3175:

3173:

3169:

3163:

3160:

3158:

3155:

3153:

3150:

3148:

3145:

3143:

3140:

3138:

3135:

3133:

3130:

3128:

3125:

3123:

3120:

3118:

3115:

3113:

3110:

3108:

3105:

3103:

3100:

3098:

3095:

3093:

3090:

3088:

3085:

3083:

3080:

3078:

3075:

3073:

3070:

3068:

3065:

3063:

3060:

3058:

3055:

3053:

3050:

3048:

3045:

3043:

3040:

3038:

3035:

3033:

3030:

3028:

3025:

3023:

3020:

3018:

3015:

3013:

3010:

3008:

3005:

3003:

3000:

2998:

2995:

2993:

2990:

2988:

2985:

2983:

2980:

2978:

2975:

2973:

2970:

2968:

2965:

2963:

2960:

2958:

2955:

2953:

2950:

2948:

2945:

2944:

2942:

2940:

2935:

2929:

2926:

2924:

2921:

2919:

2916:

2914:

2911:

2907:

2904:

2902:

2899:

2897:

2894:

2893:

2892:

2889:

2887:

2884:

2882:

2879:

2877:

2874:

2872:

2869:

2867:

2864:

2862:

2859:

2857:

2854:

2852:

2849:

2847:

2844:

2842:

2839:

2837:

2834:

2832:

2829:

2827:

2824:

2822:

2819:

2817:

2814:

2812:

2811:Moral courage

2809:

2807:

2804:

2802:

2799:

2797:

2794:

2792:

2789:

2787:

2784:

2782:

2779:

2777:

2774:

2772:

2769:

2765:

2762:

2760:

2757:

2755:

2752:

2751:

2750:

2749:Good and evil

2747:

2745:

2742:

2740:

2737:

2735:

2734:Family values

2732:

2730:

2727:

2725:

2722:

2720:

2717:

2715:

2712:

2710:

2707:

2705:

2702:

2700:

2697:

2695:

2692:

2690:

2687:

2685:

2682:

2680:

2677:

2675:

2672:

2670:

2667:

2666:

2664:

2660:

2654:

2651:

2649:

2646:

2644:

2641:

2639:

2636:

2634:

2631:

2629:

2626:

2624:

2621:

2619:

2616:

2614:

2611:

2609:

2606:

2604:

2601:

2599:

2596:

2595:

2593:

2589:

2581:

2578:

2577:

2576:

2573:

2571:

2568:

2566:

2563:

2561:

2558:

2554:

2551:

2549:

2548:Quasi-realism

2546:

2544:

2541:

2539:

2536:

2535:

2534:

2531:

2529:

2526:

2524:

2521:

2519:

2516:

2514:

2511:

2505:

2502:

2500:

2497:

2496:

2495:

2492:

2488:

2485:

2483:

2480:

2479:

2478:

2475:

2474:

2473:

2470:

2468:

2465:

2463:

2460:

2459:

2457:

2455:

2451:

2445:

2442:

2440:

2437:

2435:

2432:

2430:

2427:

2425:

2422:

2420:

2417:

2415:

2412:

2410:

2407:

2405:

2402:

2400:

2397:

2395:

2392:

2390:

2387:

2385:

2382:

2378:

2375:

2374:

2373:

2372:Environmental

2370:

2368:

2365:

2363:

2360:

2358:

2355:

2353:

2350:

2348:

2345:

2343:

2340:

2338:

2335:

2334:

2332:

2330:

2326:

2320:

2317:

2315:

2312:

2310:

2307:

2305:

2302:

2300:

2297:

2295:

2294:Particularism

2292:

2290:

2287:

2285:

2282:

2280:

2277:

2276:

2274:

2272:

2268:

2264:

2257:

2252:

2250:

2245:

2243:

2238:

2237:

2234:

2226:

2225:

2220:

2216:

2211:

2209:

2206:

2204:

2200:

2199:

2190:

2188:

2185:

2183:

2182:

2177:

2176:

2172:

2164:

2159:

2156:

2152:

2147:

2144:

2140:

2135:

2132:

2128:

2123:

2120:

2116:

2111:

2108:

2104:

2099:

2096:

2092:

2087:

2084:

2080:

2075:

2073:

2069:

2065:

2060:

2057:

2053:

2048:

2046:

2042:

2038:

2033:

2031:

2027:

2023:

2018:

2016:

2012:

2008:

2003:

2001:

1997:

1992:

1990:9780199691548

1986:

1982:

1975:

1972:

1967:

1965:9780521175081

1961:

1957:

1950:

1947:

1943:

1938:

1935:

1931:

1926:

1923:

1919:

1914:

1912:

1908:

1904:

1899:

1896:

1892:

1887:

1884:

1880:

1875:

1872:

1865:

1861:

1858:

1856:

1853:

1851:

1848:

1847:

1843:

1832:

1829:

1823:

1818:

1813:

1808:

1804:

1800:

1796:

1793:

1792:

1787:

1784:

1780:

1776:

1772:

1768:

1764:

1760:

1757:

1753:

1752:

1747:

1744:

1743:0-300-09487-6

1740:

1739:0-300-09486-8

1736:

1732:

1728:

1724:

1723:Allen W. Wood

1721:, translated

1720:

1716:

1713:

1712:0-19-875180-X

1709:

1705:

1701:

1697:

1694:, translated

1693:

1689:

1686:

1685:0-521-62695-1

1682:

1681:0-521-62235-2

1678:

1674:

1671:. Cambridge:

1670:

1666:

1662:

1658:

1653:

1652:0-87220-320-4

1649:

1648:0-87220-321-2

1645:

1641:

1637:

1634:

1633:0-87220-166-X

1630:

1629:0-87220-167-8

1626:

1622:

1618:

1615:

1614:0-915145-44-8

1611:

1610:0-915145-43-X

1607:

1603:

1599:

1595:

1594:

1592:

1591:0-915145-00-6

1588:

1587:0-915145-01-4

1584:

1580:

1576:

1572:

1568:

1565:

1561:

1557:

1553:

1549:

1545:

1540:

1539:0-02-307825-1

1536:

1532:

1528:

1524:

1520:

1517:

1516:Bobbs-Merrill

1513:

1509:

1505:

1504:

1502:

1498:

1494:

1491:

1487:

1483:

1479:

1474:

1473:0-415-07843-1

1470:

1466:

1462:

1458:

1455:

1451:

1447:

1446:

1444:

1440:

1439:The Moral Law

1436:

1433:

1429:

1425:

1421:

1417:

1416:1-55111-539-5

1413:

1409:

1405:

1401:

1397:

1394:

1393:0-486-44309-4

1390:

1386:

1382:

1378:

1375:

1374:Bobbs-Merrill

1371:

1367:

1363:

1362:

1360:

1356:

1352:

1351:

1346:

1345:

1341:

1339:

1336:

1330:

1325:

1323:

1319:

1315:

1311:

1307:

1303:

1299:

1298:His criticism

1295:

1291:

1287:

1286:

1277:

1275:

1271:

1267:

1263:

1259:

1252:

1250:

1246:

1244:

1235:

1233:

1231:

1226:

1222:

1218:

1214:

1213:

1206:

1203:

1198:

1196:

1192:

1184:

1182:

1175:

1172:

1171:

1170:

1164:Section Three

1163:

1161:

1159:

1155:

1154:

1145:

1143:

1140:

1132:

1130:

1123:

1121:

1119:

1117:

1112:

1108:

1103:

1096:

1094:

1092:

1091:universalized

1084:

1082:

1075:

1073:

1071:

1067:

1061:

1059:

1052:

1044:

1042:

1040:

1035:

1031:

1027:

1022:

1020:

1016:

1008:

1006:

1002:

999:

991:

989:

984:

982:

981:universal law

978:

972:

970:

969:

962:

957:

949:

947:

940:

938:

934:

929:

923:

921:

918:

914:

911:

902:

899:

896:

895:

893:

891:

883:

881:

879:

875:

871:

867:

859:

857:

854:

850:

847:

843:

838:

836:

832:

828:

824:

823:

818:

814:

806:

804:

802:

798:

794:

793:human welfare

790:

786:

779:The Good Will

778:

773:

770:

767:

763:

760:

759:

758:

756:

752:

751:

746:

738:

736:

734:

730:

726:

722:

718:

714:

710:

706:

702:

694:

692:

690:

686:

681:

680:

673:

671:

663:

661:

659:

655:

651:

646:

644:

640:

639:human welfare

635:

631:

627:

623:

622:

617:

613:

609:

605:

603:

599:

595:

591:

590:Ancient Greek

586:

584:

580:

572:

570:

568:

564:

560:

555:

553:

549:

545:

544:

539:

534:

532:

528:

524:

520:

519:

514:

513:

508:

504:

503:Immanuel Kant

500:

499:

494:

493:

488:

487:

482:

478:

474:

473:

464:

453:

450:

449:

442:

439:

437:

434:

433:

427:

426:

419:

416:

414:

411:

409:

406:

404:

401:

399:

396:

394:

391:

390:

384:

383:

376:

373:

371:

368:

365:

361:

359:

356:

354:

351:

349:

346:

344:

341:

339:

336:

334:

333:

329:

325:

323:

320:

318:

315:

313:

312:

308:

306:

303:

301:

298:

297:

294:

290:

285:

284:

277:

276:

275:Opus Postumum

272:

269:

263:

261:

260:

256:

254:

253:

249:

247:

246:

242:

240:

239:

235:

233:

232:

228:

226:

225:

221:

218:

215:Answering the

212:

210:

209:

203:

201:

200:

196:

195:

189:

188:

184:

180:

179:

176:

175:Immanuel Kant

172:

168:

164:

163:

155:

149:

145:

141:

137:

134:

133:Immanuel Kant

131:

127:

123:

118:

106:

95:

92:

88:

85:

81:

78:

74:

71:

67:

64: –

63:

59:

58:Find sources:

52:

48:

44:

38:

37:

36:single source

32:This article

30:

26:

21:

20:

3535:Ethics books

3500:

3496:

3486:

3477:

3471:

3463:

3459:

3455:

3451:

3447:

3442:

3407:

3363:Human rights

3306:After Virtue

3225:

3032:Schopenhauer

2806:Moral agency

2679:Common sense

2575:Universalism

2543:Expressivism

2523:Intuitionism

2494:Subjectivism

2439:Terraforming

2414:Professional

2222:

2197:

2180:

2162:

2158:

2150:

2146:

2138:

2134:

2126:

2122:

2114:

2110:

2102:

2098:

2090:

2086:

2078:

2063:

2059:

2051:

2036:

2021:

2006:

1980:

1974:

1955:

1949:

1941:

1937:

1929:

1925:

1917:

1902:

1898:

1890:

1886:

1878:

1874:

1828:Books portal

1799:Robert Stern

1789:

1766:

1762:

1749:

1718:

1698:, edited by

1696:Arnulf Zweig

1691:

1660:

1639:

1620:

1597:

1570:

1547:

1522:

1507:

1496:

1485:

1460:

1449:

1438:

1430:. New York:

1423:

1399:

1380:

1365:

1348:

1334:

1332:

1327:

1293:

1283:

1282:In his book

1281:

1272:

1268:

1264:

1260:

1256:

1247:

1239:

1216:

1210:

1207:

1201:

1199:

1194:

1188:

1179:

1167:

1152:

1149:

1136:

1127:

1114:

1110:

1106:

1104:

1100:

1088:

1079:

1069:

1065:

1064:law itself.

1062:

1054:

1038:

1033:

1029:

1025:

1023:

1015:hypothetical

1012:

1003:

997:

995:

986:

974:

968:universality

967:

963:

959:

944:

936:

931:

927:

919:

915:

907:

890:common-sense

887:

863:

848:

845:

839:

820:

810:

796:

784:

782:

748:

745:common-sense

742:

732:

728:

724:

720:

716:

704:

701:Groundwork.

700:

698:

688:

677:

674:

669:

667:

657:

653:

649:

647:

642:

619:

615:

611:

607:

606:

587:

578:

576:

566:

558:

556:

541:

535:

516:

510:

497:

496:

491:

490:

485:

484:

471:

470:

469:

408:F. H. Jacobi

393:J. G. Fichte

332:a posteriori

331:

327:

309:

273:

257:

250:

243:

236:

229:

222:

204:

197:

100:

90:

83:

76:

69:

57:

33:

3181:(c. 322 BC)

3047:Kierkegaard

2866:Stewardship

2643:Rousseauian

2560:Rationalism

2472:Cognitivism

2419:Programming

2394:Meat eating

2367:Engineering

1771:Mary Gregor

1230:consciences

1225:reciprocity

1019:categorical

1009:Imperatives

992:Section Two

870:inclination

835:inclination

739:Section One

695:Pure ethics

311:Sapere aude

192:Major works

3514:Categories

3452:Groundwork

3077:Bonhoeffer

2786:Immorality

2729:Eudaimonia

2689:Conscience

2684:Compassion

2570:Skepticism

2565:Relativism

2482:Naturalism

2462:Absolutism

2434:Technology

2284:Deontology

2181:Groundwork

2179:About the

2163:Groundwork

2151:Groundwork

2139:Groundwork

2127:Groundwork

2115:Groundwork

2103:Groundwork

2091:Groundwork

2079:Groundwork

2064:Groundwork

2052:Groundwork

2037:Groundwork

2022:Groundwork

2007:Groundwork

1942:Groundwork

1930:Groundwork

1918:Groundwork

1903:Groundwork

1891:Groundwork

1879:Groundwork

1855:Kantianism