27:

523:) held that logical statements such as these contained the most formal reality, since they are always true and unchanging, Hume held that, while true, they contain no formal reality, because the truth of the statements rests on the definitions of the words involved, and not on actual things in the world, since there is no such thing as a true triangle or exact equality of length in the world. So for this reason, relations of ideas cannot be used to prove matters of fact.

527:

cannot be used to prove matters of fact. Because of this, matters of fact have no certainty and therefore cannot be used to prove anything. Only certain things can be used to prove other things for certain, but only things about the world can be used to prove other things about the world. But since we can't cross the fork, nothing is both certain and about the world, only one or the other, and so it is impossible to prove something about the world with certainty.

534:(for example) as a matter of fact. If God is not literally made up of physical matter, and does not have an observable effect on the world , making a statement about God is not a matter of fact. Therefore, a statement about God must be a relation of ideas. In this case if we prove the statement "God exists," it doesn't really tell us anything about the world; it is just playing with words. It is easy to see how Hume's fork voids the causal argument and the

511:

dropped on Earth it went down, this does not make it logically necessary that in the future rocks will fall when in the same circumstances. Things of this nature rely upon the future conforming to the same principles which governed the past. But that isn't something that we can know based on past experience—all past experience could tell us is that in the past, the future has resembled the past.

510:

Second, Hume claims that our belief in cause-and-effect relationships between events is not grounded on reason, but rather arises merely by habit or custom. Suppose one states: "Whenever someone on earth lets go of a stone it falls." While we can grant that in every instance thus far when a rock was

514:

Third, Hume notes that relations of ideas can be used only to prove other relations of ideas, and mean nothing outside of the context of how they relate to each other, and therefore tell us nothing about the world. Take the statement "An equilateral triangle has three sides of equal length." While

526:

The results claimed by Hume as consequences of his fork are drastic. According to him, relations of ideas can be proved with certainty (by using other relations of ideas), however, they don't really mean anything about the world. Since they don't mean anything about the world, relations of ideas

538:

for the existence of a non-observable God. However, this does not mean that the validity of Hume's fork would imply that God definitely does not exist, only that it would imply that the existence of God cannot be proven as a matter of fact without worldly evidence.

351:

Hume's fork remains basic in Anglo-American philosophy. Many deceptions and confusions are foisted by surreptitious or unwitting conversion of a synthetic claim to an analytic claim, rendered true by necessity but merely a tautology, for instance the

554:, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but

402:

discoverable by the mere operation of thought ... Matters of fact, which are the second object of human reason, are not ascertained in the same manner; nor is our evidence of their truth, however great, of a like nature with the foregoing.

503:

does not exist in science. First, Hume notes that statements of the second type can never be entirely certain, due to the fallibility of our senses, the possibility of deception (see e.g. the modern

286:—combining meanings of terms with states of facts, yet known true without experience of the particular instance—replacing the two prongs of Hume's fork with a three-pronged-fork thesis (

316:

entailing both necessity and aprioricity via logic on one side and, on the other side, demand empirical verification, altogether restricting philosophical discourse to claims

1126:

332:, as every term in any statement has its meaning contingent on a vast network of knowledge and belief, the speaker's conception of the entire world. By the early 1970s,

312:

and asserted Hume's fork, so called, while hinging it at language—the analytic/synthetic division—while presuming that by holding to analyticity, they could develop a

979:

972:

560:

410:

291:

214:

792:

986:

771:

1120:

1000:

941:

708:

197:—that no amount of examination of cases will logically entail the conformity of unexamined cases—and supported Hume's aim to position

507:

theory) and other arguments made by philosophical skeptics. It is always possible that any given statement about the world is false.

1147:

359:. Simply put, Hume's fork has limitations. Related concerns are Hume's distinction of demonstrative versus probable reasoning and

1157:

1096:

1152:

677:

628:

426:

226:

101:

746:

348:

are the same star, they are the same star by necessity, but this is known true by a human only through relevant experience.

614:

1014:

1007:

297:

301:

899:

595:

965:

767:

1074:

438:

79:

73:

934:

446:

117:

649:

619:

473:

325:

270:

265:

206:

1086:

703:

329:

234:

20:

1033:

464:

1064:

1043:

205:

while combatting allegedly rampant "sophistry and illusion" by philosophers and religionists. Being a

1038:

787:

645:

535:

460:

253:

194:

1162:

1059:

927:

42:

1167:

993:

451:

305:

275:

218:

129:

68:

49:'s emphatic, 1730s division between "relations of ideas" and "matters of fact." (Alternatively,

725:

542:

Hume rejected the idea of any meaningful statement that did not fall into this schema, saying:

721:

202:

143:

531:

379:

All the objects of human reason or enquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds, to wit,

353:

155:

150:, whereas a synthetic statement, concerning external states of affairs, may be false, like

729:

317:

421:

Hume's fork is often stated in such a way that statements are divided up into two types:

189:, whereas assertions of "real existence" and traits, being synthetic, are contingent and

668:

610:

504:

313:

222:

159:

26:

282:

into the experience of space and time. Kant thus reasoned existence of the synthetic

1141:

468:

360:

261:

64:

55:

1113:

257:

137:

121:

38:

240:. Still, Hume's fork is a useful starting point to anchor philosophical scrutiny.

488:, and ideas of mathematics and logic. Into the second class fall statements like

1091:

1080:

699:

587:

551:

430:

333:

321:

230:

210:

182:

163:

113:

109:

221:." In the 1930s, the logical empiricists staked Hume's fork. Yet in the 1950s,

950:

396:

364:

279:

249:

46:

624:

555:

520:

500:

434:

96:

71:, Hume's fork asserts that all statements are exclusively either "analytic

67:

1780s characterization of Hume's thesis, and furthered in the 1930s by the

905:

547:

388:

198:

672:

392:

375:

The first distinction is between two different areas of human study:

142:. An analytic statement is true via its terms' meanings alone, hence

60:

516:

345:

341:

278:

by the mind's aligning the environmental input by arranging those

178:

25:

363:. Hume makes other, important two-category distinctions, such as

530:

If accepted, Hume's fork makes it pointless to try to prove the

923:

459:

In modern terminology, members of the first group are known as

87:

or, however apparently probable, are unknowable without exact

919:

726:"The problem of metaphysics: The 'new' metaphysics; Modality"

174:

is knowable only upon, experience in the area of interest.

328:

undermined the analytic/synthetic division by explicating

177:

By Hume's fork, sheer conceptual derivations (ostensibly,

162:, whereas the contingent hinges on the world's state, a

615:

ch. 2 "Hume's theory of knowledge (I): 'Hume's fork' "

274:, where Kant attributed to the mind a causal role in

83:," which, respectively, are universally true by mere

620:

30:

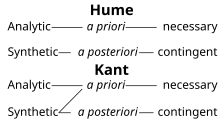

Hume's fork contrasted with Kant's trident/pitchfork

1127:

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence

1105:

1052:

1026:

957:

833:

745:Leah Henderson, "The problem of induction", sec. 2

594:, rev 2nd edn (New York: St Martin's Press, 1984),

818:Nicholas Bunnin & Jiyuan Yu. "Hume's Fork".

445:Statements about the world. These are synthetic,

193:. Hume's own, simpler, distinction concerned the

640:Nicholas Bunnin & Jiyuan Yu, "Hume's fork",

807:Kant and the Foundations of Analytic Philosophy

980:An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

844:Nicholas Bunnin and Jiyuan Yu, "Hume's Fork".

642:The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy

631:introducing Kant's formulation of Hume's fork.

1034:Argument for the existence of God from design

935:

480:Into the first class fall statements such as

8:

846:Blackwell's Dictionary of Western Philosophy

820:Blackwell's Dictionary of Western Philosophy

724:& Meghan Sullivan, "Metaphysics", § 3.1

942:

928:

920:

973:An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

901:An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

561:An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

411:An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

515:some earlier philosophers (most notably

387:. Of the first kind are the sciences of

209:, Kant asserted both the hope of a true

793:The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

573:

217:by defying Hume's fork to declare the "

987:Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary

870:Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

858:Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

583:

581:

579:

577:

546:If we take in our hand any volume; of

371:Relations of ideas and matters of fact

252:, as in Hume's fork as well as Hume's

53:may refer to what is otherwise termed

1121:A Treatise of Human Nature (Abstract)

1001:Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

300:, Newton's theory fell to Einstein's

292:Newton's law of universal gravitation

215:Newton's law of universal gravitation

185:), being analytic, are necessary and

7:

881:

782:

780:

704:"The analytic/synthetic distinction"

695:

693:

691:

664:

662:

660:

658:

606:

604:

19:For the novel of the same name, see

904:. London: A. Millar. Archived from

751:Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

734:Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

709:Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

425:Statements about ideas. These are

14:

367:and as impressions versus ideas.

170:is knowable without, whereas the

120:, and the statement's purported

884:, p. 166, emphasis removed

809:. Clarendon Press, 2004. p. 28.

678:History of Philosophy Quarterly

158:, the necessary is true in all

490:"the sun rises in the morning"

467:. This terminology comes from

227:analytic/synthetic distinction

94:By Hume's fork, a statement's

41:, is a tenet elaborating upon

1:

764:The Suasive Art of David Hume

486:"all bachelors are unmarried"

463:and members of the latter as

1015:The History of Great Britain

302:general theory of relativity

1097:Price–specie flow mechanism

790:, in Edward N. Zalta, ed.,

749:, in Edward N. Zalta, ed.,

706:, in Edward N. Zalta, ed.,

256:, was taken as a threat to

1184:

966:A Treatise of Human Nature

768:Princeton University Press

592:A Dictionary of Philosophy

336:established the necessary

308:rejected Kant's synthetic

18:

1075:The Missing Shade of Blue

499:Hume wants to prove that

482:"all bodies are extended"

304:. In the late 1920s, the

1148:Concepts in epistemology

623:(London & New York:

213:, and a literal view of

102:analytic or is synthetic

1158:Conceptual distinctions

673:"Hume's fork revisited"

474:Critique of Pure Reason

326:Willard Van Orman Quine

324:. In the early 1950s,

271:Critique of Pure Reason

266:Transcendental Idealism

207:transcendental idealist

148:Bachelors are unmarried

1153:Philosophy of language

1087:Scottish Enlightenment

1008:The History of England

835:, 2nd Edition, p. 218.

565:

494:"all bodies have mass"

465:synthetic propositions

365:beliefs versus desires

330:ontological relativity

260:'s theory of motion.

31:

898:Hume, David (1777) .

872:, Section IV, Part I.

544:

461:analytic propositions

29:

1039:Problem of induction

646:Blackwell Publishing

536:ontological argument

254:problem of induction

229:. And in the 1970s,

195:problem of induction

108:—its agreement with

822:. Blackwell, 2004.

747:"Hume on induction"

306:logical positivists

264:responded with his

152:Bachelors age badly

69:logical empiricists

21:Hume's Fork (novel)

994:Four Dissertations

848:. Blackwell, 2004.

381:relations of ideas

290:) and thus saving

276:sensory experience

219:synthetic a priori

154:. By mere logical

144:true by definition

104:, the statement's

43:British empiricist

32:

16:English philosophy

1135:

1134:

831:Garrett Thomson,

722:Peter van Inwagen

471:(Introduction to

203:empirical science

63:.) As phrased in

1175:

1060:Hume's principle

1044:Is–ought problem

944:

937:

930:

921:

916:

914:

913:

885:

879:

873:

867:

861:

855:

849:

842:

836:

829:

823:

816:

810:

803:

797:

784:

775:

766:(Princeton, NJ:

760:

754:

743:

737:

719:

713:

697:

686:

666:

653:

638:

632:

608:

599:

585:

558:and illusion. —

532:existence of God

355:No true Scotsman

288:Kant's pitchfork

233:established the

141:

133:

77:" or "synthetic

1183:

1182:

1178:

1177:

1176:

1174:

1173:

1172:

1138:

1137:

1136:

1131:

1101:

1048:

1022:

953:

948:

911:

909:

897:

894:

889:

888:

880:

876:

868:

864:

856:

852:

843:

839:

830:

826:

817:

813:

805:Hanna, Robert,

804:

800:

785:

778:

761:

757:

744:

740:

730:Edward N. Zalta

720:

716:

698:

689:

667:

656:

639:

635:

609:

602:

586:

575:

570:

477:, Section IV).

449:, and knowable

385:matters of fact

373:

340:, since if the

246:

225:undermined its

166:basis. And the

160:possible worlds

135:

127:

65:Immanuel Kant's

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1181:

1179:

1171:

1170:

1165:

1160:

1155:

1150:

1140:

1139:

1133:

1132:

1130:

1129:

1124:

1117:

1109:

1107:

1103:

1102:

1100:

1099:

1094:

1089:

1084:

1077:

1072:

1067:

1062:

1056:

1054:

1050:

1049:

1047:

1046:

1041:

1036:

1030:

1028:

1024:

1023:

1021:

1020:

1019:

1018:

1004:

997:

990:

983:

976:

969:

961:

959:

955:

954:

949:

947:

946:

939:

932:

924:

918:

917:

893:

890:

887:

886:

874:

862:

850:

837:

824:

811:

798:

796:(Spring 2013).

786:James Fetzer,

776:

755:

753:(Spring 2020).

738:

736:(Spring 2020).

714:

687:

669:Georges Dicker

654:

633:

611:Georges Dicker

600:

572:

571:

569:

566:

505:brain in a vat

457:

456:

443:

419:

418:

417:

416:

415:

414:

372:

369:

314:logical syntax

248:Hume's strong

245:

242:

110:the real world

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1180:

1169:

1166:

1164:

1161:

1159:

1156:

1154:

1151:

1149:

1146:

1145:

1143:

1128:

1125:

1123:

1122:

1118:

1116:

1115:

1111:

1110:

1108:

1104:

1098:

1095:

1093:

1090:

1088:

1085:

1082:

1078:

1076:

1073:

1071:

1068:

1066:

1063:

1061:

1058:

1057:

1055:

1051:

1045:

1042:

1040:

1037:

1035:

1032:

1031:

1029:

1025:

1017:

1016:

1012:

1011:

1010:

1009:

1005:

1003:

1002:

998:

996:

995:

991:

989:

988:

984:

982:

981:

977:

975:

974:

970:

968:

967:

963:

962:

960:

956:

952:

945:

940:

938:

933:

931:

926:

925:

922:

908:on 2018-07-10

907:

903:

902:

896:

895:

891:

883:

878:

875:

871:

866:

863:

860:, Section II.

859:

854:

851:

847:

841:

838:

834:

828:

825:

821:

815:

812:

808:

802:

799:

795:

794:

789:

788:"Carl Hempel"

783:

781:

777:

773:

769:

765:

759:

756:

752:

748:

742:

739:

735:

731:

727:

723:

718:

715:

711:

710:

705:

701:

696:

694:

692:

688:

684:

680:

679:

674:

670:

665:

663:

661:

659:

655:

651:

647:

644:(Malden, MA:

643:

637:

634:

630:

626:

622:

621:

616:

612:

607:

605:

601:

597:

593:

589:

584:

582:

580:

578:

574:

567:

564:

563:

562:

557:

553:

549:

543:

540:

537:

533:

528:

524:

522:

518:

512:

508:

506:

502:

497:

495:

491:

487:

483:

478:

476:

475:

470:

466:

462:

454:

453:

448:

444:

441:

440:

436:

432:

428:

424:

423:

422:

413:

412:

407:

406:

405:

404:

401:

398:

394:

390:

386:

382:

378:

377:

376:

370:

368:

366:

362:

358:

356:

349:

347:

343:

339:

335:

331:

327:

323:

322:false or true

319:

315:

311:

307:

303:

299:

295:

293:

289:

285:

281:

277:

273:

272:

267:

263:

262:Immanuel Kant

259:

255:

251:

243:

241:

239:

238:

232:

228:

224:

223:W. V. O Quine

220:

216:

212:

208:

204:

200:

196:

192:

188:

184:

180:

175:

173:

169:

165:

161:

157:

153:

149:

145:

140:

139:

132:

131:

125:

124:

119:

115:

111:

107:

103:

99:

98:

92:

90:

86:

82:

81:

76:

75:

70:

66:

62:

59:, a tenet of

58:

57:

52:

48:

44:

40:

36:

28:

22:

1119:

1114:Hume Studies

1112:

1069:

1013:

1006:

999:

992:

985:

978:

971:

964:

910:. Retrieved

906:the original

900:

877:

869:

865:

857:

853:

845:

840:

832:

827:

819:

814:

806:

801:

791:

763:

758:

750:

741:

733:

717:

712:(Fall 2018).

707:

685:(4):327–342.

682:

676:

641:

636:

618:

591:

559:

545:

541:

529:

525:

513:

509:

498:

493:

489:

485:

481:

479:

472:

458:

452:a posteriori

450:

437:

420:

409:

400:

384:

380:

374:

354:

350:

346:Evening Star

342:Morning Star

338:a posteriori

337:

309:

296:

287:

283:

269:

268:in his 1781

247:

237:a posteriori

236:

201:on par with

191:a posteriori

190:

186:

176:

172:a posteriori

171:

167:

164:metaphysical

151:

147:

138:a posteriori

136:

128:

122:

105:

95:

93:

88:

84:

80:a posteriori

78:

72:

54:

50:

45:philosopher

39:epistemology

34:

33:

1081:Of Miracles

1070:Hume's fork

762:M. A. Box,

700:Georges Rey

681:, 1991 Oct;

588:Antony Flew

552:metaphysics

334:Saul Kripke

231:Saul Kripke

211:metaphysics

183:mathematics

112:—either is

51:Hume's fork

35:Hume's fork

1163:David Hume

1142:Categories

1092:Empiricism

1065:Hume's law

1053:Philosophy

951:David Hume

912:2015-08-31

892:References

550:or school

447:contingent

397:Arithmetic

361:Hume's law

320:as either

318:verifiable

280:sense data

250:empiricism

235:necessary

126:either is

118:contingent

100:either is

89:experience

85:definition

56:Hume's law

47:David Hume

1168:Humeanism

1027:Criticism

882:Hume 1777

772:pp. 39–41

770:, 1990),

648:, 2004),

627:, 1998),

625:Routledge

556:sophistry

521:Descartes

501:certainty

431:necessary

123:knowledge

114:necessary

548:divinity

439:a priori

435:knowable

427:analytic

389:Geometry

344:and the

310:a priori

284:a priori

199:humanism

187:a priori

168:a priori

156:validity

130:a priori

74:a priori

1106:Related

732:, ed.,

393:Algebra

298:In 1919

244:History

146:, like

97:meaning

596:p. 156

492:, and

433:, and

395:, and

383:, and

258:Newton

134:or is

116:or is

61:ethics

958:Books

728:, in

650:p 314

629:p. 41

568:Notes

517:Plato

179:logic

106:truth

37:, in

519:and

469:Kant

357:move

181:and

399:...

1144::

779:^

702:,

690:^

675:,

671:,

657:^

617:,

613:,

603:^

590:,

576:^

496:.

484:,

429:,

408:—

391:,

294:.

91:.

1083:"

1079:"

943:e

936:t

929:v

915:.

774:.

683:8

652:.

598:.

455:.

442:.

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.