200:), which many researchers now believe control the light entrainment effect of the phase response curve. In the human eye, the ipRGCs have the greatest response to light in the 460–480 nm (blue) range. In one experiment, 400 lux of blue light produced the same effects as 10,000 lux of white light from a fluorescent source. A theory of spectral opponency, in which the addition of other spectral colors renders blue light less effective for circadian phototransduction, was supported by research reported in 2005.

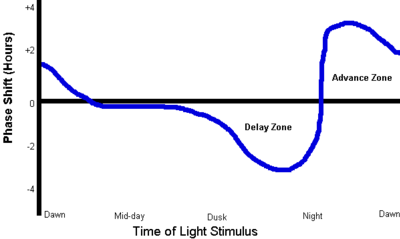

128:-axis is vague: dawn – mid-day – dusk – night – dawn. These times do not refer to actual sun-up etc. nor to specific clock times. Each individual has their own circadian "clock" and chronotype, and dawn in the illustration refers to an individual's time of spontaneous awakening when well-rested and sleeping regularly. The PRC shows when a stimulus, in this case light to the eyes, will effect a change, an advance or a delay. The curve's highest point coincides with the subject's lowest body temperature.

108:, usually taken orally. Either or both can be used daily. The phase adjustment is generally cumulative with consecutive daily administrations, and — at least partially — additive with concurrent administrations of distinct treatments. If the underlying disturbance is stable in nature, ongoing daily intervention is usually required. For jet lag, the intervention serves mainly to accelerate natural alignment, and ceases once desired alignment is achieved.

212:(externally administered) melatonin has a slight phase-delaying effect. The amount of phase-delay increases until about eight hours after wake-up time, when the effect swings abruptly from strong phase delay to strong phase advance. The phase-advance effect diminishes as the day goes on until it reaches zero about bedtime. From usual bedtime until wake-up time, exogenous melatonin has no effect on circadian phase.

282:, kept in constant darkness, responded to pulses of light exposure. The response varied according to the time of day – that is, the animals' subjective "day" – when light was administered. When DeCoursey plotted all her data relating the quantity and direction (advance or delay) of phase-shift on a single curve, she created the PRC. It has since been a standard tool in the study of biological rhythms.

300:. The neuronal PRCs can be classified as being purely positive (PRC type I) or as having negative parts (PRC type II). Importantly, the PRC type exhibited by a neuron is indicative of its input–output function (excitability) as well as synchronization behavior: networks of PRC type II neurons can synchronize their activity via mutual excitatory connections, but those of PRC type I can not.

112:

be specific to the experimental setting and not generally available in clinical practice (e.g. for melatonin, one sustained-release formulation might differ in its release rate as compared to another); also, while the magnitude is dose-dependent, not all PRC graphs cover a range of doses. The discussions below are restricted to the PRCs for the light and melatonin in humans.

83:-axis. Each curve has one peak and one trough in each 24-hour cycle. Relative circadian time is plotted against phase-shift magnitude. The treatment is usually narrowly specified as a set intensity and colour and duration of light exposure to the retina and skin, or a set dose and formulation of melatonin.

173:

Light therapy, typically with a light box producing 10,000 lux at a prescribed distance, can be used in the evening to delay or in the morning to advance an individual's sleep timing. Because losing sleep to obtain bright light exposure is considered undesirable by most people, and because it is

140:

About five hours after usual bedtime, coinciding with the body temperature trough (the lowest point of the core body temperature during sleep) the PRC peaks and the effect changes abruptly from phase delay to phase advance. Immediately after this peak, light exposure has its greatest phase-advancing

111:

Note that phase response curves from the experimental setting are usually aggregates of the test population, that there can be mild or significant variation within the test population, that individuals with sleep disorders often respond atypically, and that the formulation of the chronobiotic might

86:

These curves are often consulted in the therapeutic setting. Normally, the body's various physiological rhythms will be synchronized within an individual organism (human or animal), usually with respect to a master biological clock. Of particular importance is the sleep–wake cycle. Various sleep

253:

hours. All times are approximate and vary from one individual to another. In particular, there is no convenient way to accurately determine the times of the peaks and zero-crossings of these curves in an individual. Administration of light or melatonin close to the time at which the effect is

303:

Experimental estimation of PRC in living, regular-spiking neurons involves measuring the changes in inter-spike interval in response to a small perturbation, such as a transient pulse of current. Notably, the PRC of a neuron is not fixed but may change when firing frequency or

132:

Starting about two hours before an individual's regular bedtime, exposure of the eyes to light will delay the circadian phase, causing later wake-up time and later sleep onset. The delaying effect gets stronger as evening progresses; it is also dependent on the wavelength and

99:

usually maintain a consistent clock, but find that their natural clock does not align with the expectations of their social environment. PRC curves provide a starting point for therapeutic intervention. The two common treatments used to shift the timing of sleep are

63:

to a regular periodicity in the external environment (usually governed by the solar day). In most organisms, a stable phase relationship is desired, though in some cases the desired phase will vary by season, especially among mammals with seasonal mating habits.

174:

very difficult to estimate exactly when the greatest effect (the PRC peak) will occur in an individual, the treatment is usually applied daily just prior to bedtime (to achieve phase delay), or just after spontaneous awakening (to achieve phase advance).

121:

52:

75:'s time of administration (relative to the internal circadian clock) and the magnitude of the treatment's effect on circadian phase. Specifically, a PRC is a graph showing, by convention, time of the subject's endogenous day along the

242:

showed that a combination of morning bright light and afternoon melatonin, both timed to phase advance according to the respective PRCs, produce a larger phase advance shift than bright light alone, for a total of up to

148:

During the period between two hours after usual wake-up time and two hours before usual bedtime, light exposure has little or no effect on circadian phase (slight effects generally cancelling each other out).

1103:

Rosenthal NE, Joseph-Vanderpool JR, Levendosky AA, Johnston SH, Allen R, Kelly KA, et al. (August 1990). "Phase-shifting effects of bright morning light as treatment for delayed sleep phase syndrome".

197:

266:, showed that in humans "Exercise elicits circadian phase‐shifting effects, but additional information is needed. Significant phase–response curves were established for

223:, DLMO. This stimulates the phase-advance portion of the PRC and helps keep the body on a regular sleep-wake schedule. It also helps prepare the body for sleep.

1125:

Lewy A, Sack R, Fredrickson R (1983). "The use of bright light in the treatment of chronobiologic sleep and mood disorders: The phase-response curve".

864:

208:

The phase response curve for melatonin is roughly twelve hours out of phase with the phase response curve for light. At spontaneous wake-up time,

141:

effect, causing earlier wake-up and sleep onset. Again, illuminance greatly affects results; indoor light may be less than 500 lux while

145:

uses up to 10,000 lux. The effect diminishes until about two hours after spontaneous wake-up time, when it reaches approximately zero.

270:

onset and acrophase with large phase delays from 7:00 pm to 10:00 pm and large phase advances at both 7:00 am and from 1:00 pm to 4:00 pm"

92:

554:

Figueiro MG, Bullough JD, Bierman A, Rea MS (October 2005). "Demonstration of additivity failure in human circadian phototransduction".

1138:

Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM, Sack RL (October 1992). "Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve".

581:

Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM, Sack RL (October 1992). "Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve".

989:

278:

The first published usage of the term "phase response curve" was in 1960 by

Patricia DeCoursey. The "daily" activity rhythms of her

254:

expected to change sense abruptly may, if the changeover time is not accurately known, produce an opposite effect to that desired.

322:

1227:

900:

Gutkin BS, Ermentrout GB, Reyes AD (August 2005). "Phase-response curves give the responses of neurons to transient inputs".

1169:"Lack of short-wavelength light during the school day delays dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) in middle school students"

327:

182:

296:

Phase response curve analysis can be used to understand the intrinsic properties and oscillatory behavior of regular-

508:

59:

In humans and animals, there is a regulatory system that governs the phase relationship of an organism's internal

39:

at which it is received. PRCs are used in various fields; examples of biological oscillations are the heartbeat,

1232:

1217:

305:

177:

In addition to its use in the adjustment of circadian rhythms, light therapy is used as treatment for several

872:

1222:

1212:

909:

32:

990:"Layer and frequency dependencies of phase response properties of pyramidal neurons in rat motor cortex"

1041:"Cholinergic neuromodulation changes phase response curve shape and type in cortical pyramidal neurons"

495:

1052:

360:

230:(sleep-inducing) effect. The expected effect on sleep phase timing, if any, is predicted by the PRC.

914:

219:) melatonin starting about two hours before bedtime, provided the lighting is dim. This is known as

438:

153:

767:"Advancing human circadian rhythms with afternoon melatonin and morning intermittent bright light"

509:"Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder with blue narrow-band light-emitting diodes (LEDs)"

1017:

970:

536:

267:

1025:

1190:

1155:

1113:

1080:

1009:

962:

927:

885:

845:

796:

747:

696:

647:

598:

563:

528:

419:

1180:

1147:

1070:

1060:

1001:

954:

919:

835:

827:

786:

778:

737:

727:

686:

678:

637:

629:

590:

520:

469:

409:

401:

368:

291:

189:

68:

40:

279:

60:

137:("brightness") of the light. The effect is small if indoor lighting is dim (< 3 Lux).

1056:

364:

1185:

1168:

1075:

1040:

840:

815:

791:

766:

742:

715:

691:

666:

642:

617:

414:

389:

297:

43:, and the regular, repetitive firing observed in some neurons in the absence of noise.

28:

1206:

1005:

945:

Ermentrout B (July 1996). "Type I membranes, phase resetting curves, and synchrony".

457:

317:

178:

142:

101:

36:

974:

540:

1021:

524:

72:

1065:

633:

405:

192:

researchers led by David Berson announced the discovery of special cells in the

134:

765:

Revell VL, Burgess HJ, Gazda CJ, Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI (January 2006).

618:"A three pulse phase response curve to three milligrams of melatonin in humans"

390:"A three pulse phase response curve to three milligrams of melatonin in humans"

95:

often experience an inability to maintain a consistent internal clock. Extreme

1151:

958:

594:

373:

348:

216:

96:

51:

732:

209:

193:

105:

1194:

1084:

1013:

931:

849:

800:

751:

716:"Timing of sleep and its relationship with the endogenous melatonin rhythm"

700:

651:

567:

532:

423:

1159:

1117:

966:

923:

602:

782:

682:

227:

474:

88:

120:

831:

714:

Sletten TL, Vincenzi S, Redman JR, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SM (2010).

507:

Glickman G, Byrne B, Pineda C, Hauck WW, Brainard GC (March 2006).

884:

the single most important methodological tool in the study of all

119:

50:

1039:

Stiefel KM, Gutkin BS, Sejnowski TJ (2008). Ermentrout B (ed.).

55:

Phase response curves for light and for melatonin administration

667:"Clinical implications of the melatonin phase response curve"

79:-axis and the amount of the phase shift (in hours) along the

104:, directed at the eyes, and administration of the hormone

496:

Brown

Scientists Uncover Inner Workings of Rare Eye Cells

226:

Administration of melatonin at any time may have a mild

167:

Advance region: morning light shifts sleepiness earlier

71:

research, a PRC illustrates the relationship between a

458:"An insight into light as a chronobiological therapy"

816:"Human circadian phase-response curves for exercise"

771:

The

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

671:

The

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

814:Youngstedt SD, Elliott JA, Kripke DF (April 2019).

198:

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells

161:

Delay region: evening light shifts sleepiness later

988:Tsubo Y, Takada M, Reyes AD, Fukai T (June 2007).

616:Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Eastman CI (January 2008).

456:Walsh J, Atkinson LA, Corlett SA, Lall GS (2014).

388:Burgess HJ, Revell VL, Eastman CI (January 2008).

35:induced by a perturbation as a function of the

156:. Within that image, the explanatory text is

8:

87:disorders and externals stresses (such as

1184:

1074:

1064:

913:

839:

790:

741:

731:

690:

641:

473:

413:

372:

339:

91:) can interfere with this. Humans with

152:Another image of the PRC for light is

865:"Clock Tutorial #3c - Darwin On Time"

7:

994:The European Journal of Neuroscience

262:In a 2019 study Shawn D. Youngstedt

27:) illustrates the transient change (

238:In a 2006 study Victoria L. Revell

871:. ScienceBlogs LLC. Archived from

14:

215:The human body produces its own (

1006:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05579.x

308:state of the neuron is changed.

323:Circadian rhythm sleep disorder

93:non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder

525:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.006

1:

437:Kripke DF, Loving RT (2001).

1167:Figueiro MG, Rea MS (2010).

1066:10.1371/journal.pone.0003947

634:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143180

462:ChronoPhysiology and Therapy

406:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143180

328:Delayed sleep phase disorder

31:) in the cycle period of an

1173:Neuro Endocrinology Letters

1140:Chronobiology International

583:Chronobiology International

556:Neuro Endocrinology Letters

439:"Bringing Therapy to Light"

183:seasonal affective disorder

1249:

902:Journal of Neurophysiology

289:

268:aMT6(melatonin derivative)

1152:10.3109/07420529209064550

959:10.1162/neco.1996.8.5.979

820:The Journal of Physiology

622:The Journal of Physiology

595:10.3109/07420529209064550

394:The Journal of Physiology

374:10.4249/scholarpedia.1332

221:dim-light melatonin onset

733:10.3389/fneur.2010.00137

869:A Blog Around the Clock

16:Graph of phase response

720:Frontiers in Neurology

349:"Phase response curve"

129:

124:The time shown on the

56:

1228:Neuroscience of sleep

924:10.1152/jn.00359.2004

513:Biological Psychiatry

290:Further information:

123:

54:

1127:Psychopharmacol Bull

783:10.1210/jc.2005-1009

683:10.1210/jc.2010-1031

665:Lewy A (July 2010).

347:Canavier CC (2006).

47:In circadian rhythms

21:phase response curve

1057:2008PLoSO...3.3947S

863:Zivkovic B (2007).

365:2006SchpJ...1.1332C

179:affective disorders

947:Neural Computation

886:biological rhythms

475:10.2147/CPT.S56589

130:

57:

41:circadian rhythms

1240:

1233:Sleep physiology

1218:Circadian rhythm

1198:

1188:

1163:

1134:

1121:

1089:

1088:

1078:

1068:

1036:

1030:

1029:

1024:. Archived from

985:

979:

978:

942:

936:

935:

917:

897:

891:

890:

881:

880:

860:

854:

853:

843:

832:10.1113/JP276943

826:(8): 2253–2268.

811:

805:

804:

794:

762:

756:

755:

745:

735:

711:

705:

704:

694:

662:

656:

655:

645:

613:

607:

606:

578:

572:

571:

551:

545:

544:

504:

498:

493:

487:

486:

484:

482:

477:

453:

447:

446:

434:

428:

427:

417:

385:

379:

378:

376:

344:

292:Phase precession

280:flying squirrels

252:

251:

247:

234:Additive effects

190:Brown University

69:circadian rhythm

1248:

1247:

1243:

1242:

1241:

1239:

1238:

1237:

1203:

1202:

1201:

1166:

1137:

1124:

1102:

1098:

1096:Further reading

1093:

1092:

1038:

1037:

1033:

1000:(11): 3429–41.

987:

986:

982:

953:(5): 979–1001.

944:

943:

939:

915:10.1.1.232.4206

899:

898:

894:

878:

876:

862:

861:

857:

813:

812:

808:

764:

763:

759:

713:

712:

708:

664:

663:

659:

615:

614:

610:

580:

579:

575:

553:

552:

548:

506:

505:

501:

494:

490:

480:

478:

455:

454:

450:

436:

435:

431:

387:

386:

382:

346:

345:

341:

336:

314:

306:neuromodulatory

298:spiking neurons

294:

288:

276:

260:

249:

245:

244:

236:

206:

154:here (Figure 1)

118:

61:circadian clock

49:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1246:

1244:

1236:

1235:

1230:

1225:

1220:

1215:

1205:

1204:

1200:

1199:

1164:

1135:

1122:

1099:

1097:

1094:

1091:

1090:

1031:

1028:on 2013-01-05.

980:

937:

908:(2): 1623–35.

892:

855:

806:

757:

706:

677:(7): 3158–60.

657:

608:

573:

546:

499:

488:

448:

429:

380:

338:

337:

335:

332:

331:

330:

325:

320:

313:

310:

287:

284:

275:

272:

259:

256:

235:

232:

205:

202:

171:

170:

164:

117:

114:

48:

45:

29:phase response

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1245:

1234:

1231:

1229:

1226:

1224:

1223:Neural coding

1221:

1219:

1216:

1214:

1213:Chronobiology

1211:

1210:

1208:

1196:

1192:

1187:

1182:

1178:

1174:

1170:

1165:

1161:

1157:

1153:

1149:

1146:(5): 380–92.

1145:

1141:

1136:

1132:

1128:

1123:

1119:

1115:

1112:(4): 354–61.

1111:

1107:

1101:

1100:

1095:

1086:

1082:

1077:

1072:

1067:

1062:

1058:

1054:

1051:(12): e3947.

1050:

1046:

1042:

1035:

1032:

1027:

1023:

1019:

1015:

1011:

1007:

1003:

999:

995:

991:

984:

981:

976:

972:

968:

964:

960:

956:

952:

948:

941:

938:

933:

929:

925:

921:

916:

911:

907:

903:

896:

893:

889:

887:

875:on 2012-05-19

874:

870:

866:

859:

856:

851:

847:

842:

837:

833:

829:

825:

821:

817:

810:

807:

802:

798:

793:

788:

784:

780:

776:

772:

768:

761:

758:

753:

749:

744:

739:

734:

729:

725:

721:

717:

710:

707:

702:

698:

693:

688:

684:

680:

676:

672:

668:

661:

658:

653:

649:

644:

639:

635:

631:

628:(2): 639–47.

627:

623:

619:

612:

609:

604:

600:

596:

592:

589:(5): 380–92.

588:

584:

577:

574:

569:

565:

561:

557:

550:

547:

542:

538:

534:

530:

526:

522:

518:

514:

510:

503:

500:

497:

492:

489:

476:

471:

467:

463:

459:

452:

449:

444:

440:

433:

430:

425:

421:

416:

411:

407:

403:

400:(2): 639–47.

399:

395:

391:

384:

381:

375:

370:

366:

362:

358:

354:

350:

343:

340:

333:

329:

326:

324:

321:

319:

318:Chronobiology

316:

315:

311:

309:

307:

301:

299:

293:

285:

283:

281:

273:

271:

269:

265:

257:

255:

241:

233:

231:

229:

224:

222:

218:

213:

211:

203:

201:

199:

195:

191:

186:

184:

180:

175:

168:

165:

162:

159:

158:

157:

155:

150:

146:

144:

143:light therapy

138:

136:

127:

122:

115:

113:

109:

107:

103:

102:light therapy

98:

94:

90:

84:

82:

78:

74:

70:

65:

62:

53:

46:

44:

42:

38:

34:

30:

26:

22:

1176:

1172:

1143:

1139:

1130:

1126:

1109:

1105:

1048:

1044:

1034:

1026:the original

997:

993:

983:

950:

946:

940:

905:

901:

895:

883:

877:. Retrieved

873:the original

868:

858:

823:

819:

809:

774:

770:

760:

723:

719:

709:

674:

670:

660:

625:

621:

611:

586:

582:

576:

562:(5): 493–8.

559:

555:

549:

519:(6): 502–7.

516:

512:

502:

491:

479:. Retrieved

465:

461:

451:

443:Sleep Review

442:

432:

397:

393:

383:

359:(12): 1332.

356:

353:Scholarpedia

352:

342:

302:

295:

277:

263:

261:

239:

237:

225:

220:

214:

207:

187:

176:

172:

166:

160:

151:

147:

139:

131:

125:

110:

85:

80:

76:

73:chronobiotic

66:

58:

24:

20:

18:

1179:(1): 92–6.

777:(1): 54–9.

135:illuminance

97:chronotypes

33:oscillation

1207:Categories

879:2007-11-03

334:References

286:In neurons

217:endogenous

196:, ipRGCs (

181:including

910:CiteSeerX

468:: 79–85.

210:exogenous

204:Melatonin

194:human eye

106:melatonin

1195:20150866

1133:: 523–5.

1085:19079601

1045:PLOS ONE

1014:17553012

975:17168880

932:15829595

850:30784068

801:16263827

752:21188265

701:20610608

652:18006583

568:16264413

541:42586876

533:16165105

424:18006583

312:See also

258:Exercise

228:hypnotic

188:In 2002

1186:3349218

1160:1394610

1118:2267478

1076:2596483

1053:Bibcode

1022:1232793

967:8697231

841:6462487

792:3841985

743:3008942

726:: 137.

692:2928905

643:2375577

603:1394610

415:2375577

361:Bibcode

248:⁄

185:(SAD).

89:jet lag

1193:

1183:

1158:

1116:

1083:

1073:

1020:

1012:

973:

965:

930:

912:

848:

838:

799:

789:

750:

740:

699:

689:

650:

640:

601:

566:

539:

531:

481:31 May

422:

412:

274:Origin

264:et al.

240:et al.

1106:Sleep

1018:S2CID

971:S2CID

537:S2CID

116:Light

37:phase

1191:PMID

1156:PMID

1114:PMID

1081:PMID

1010:PMID

963:PMID

928:PMID

846:PMID

797:PMID

748:PMID

697:PMID

648:PMID

599:PMID

564:PMID

529:PMID

483:2015

445:(1).

420:PMID

1181:PMC

1148:doi

1071:PMC

1061:doi

1002:doi

955:doi

920:doi

836:PMC

828:doi

824:597

787:PMC

779:doi

738:PMC

728:doi

687:PMC

679:doi

638:PMC

630:doi

626:586

591:doi

521:doi

470:doi

410:PMC

402:doi

398:586

369:doi

163:and

67:In

25:PRC

1209::

1189:.

1177:31

1175:.

1171:.

1154:.

1142:.

1131:19

1129:.

1110:13

1108:.

1079:.

1069:.

1059:.

1047:.

1043:.

1016:.

1008:.

998:25

996:.

992:.

969:.

961:.

949:.

926:.

918:.

906:94

904:.

882:.

867:.

844:.

834:.

822:.

818:.

795:.

785:.

775:91

773:.

769:.

746:.

736:.

722:.

718:.

695:.

685:.

675:95

673:.

669:.

646:.

636:.

624:.

620:.

597:.

585:.

560:26

558:.

535:.

527:.

517:59

515:.

511:.

464:.

460:.

441:.

418:.

408:.

396:.

392:.

367:.

355:.

351:.

19:A

1197:.

1162:.

1150::

1144:9

1120:.

1087:.

1063::

1055::

1049:3

1004::

977:.

957::

951:8

934:.

922::

888:.

852:.

830::

803:.

781::

754:.

730::

724:1

703:.

681::

654:.

632::

605:.

593::

587:9

570:.

543:.

523::

485:.

472::

466:4

426:.

404::

377:.

371::

363::

357:1

250:2

246:1

243:2

169:.

126:x

81:y

77:x

23:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.