237:

No. 58 of Asher's genuine responsa). "Besamim Rosh" ascribes the following opinions to the neo-Talmudists of the thirteenth century: "Articles of faith must be adapted to the times; and at present the most essential article is that we all are utterly worthless and depraved, and that our only duty consists in loving truth and peace and learning to know God and His works" (l.c.). One of the controversial responsum in the "Besamim Rosh" stated that the historical Jewish customs against mourning for someone who committed suicide and likewise not burying someone who committed suicide in a Jewish cemetery were not applicable because of the terrible difficulties facing the Jews. In other words, it would be permissible to mourn for someone who committed suicide due to depression. This ruling on laws of mourning for death from suicide from the "Besamim Rosh" would be cited by

203:, and then argued deception in a circular letter addressed to Berlin's father, by critically analyzing the responsa and arguing that they were spurious. Levin tried in vain to defend his son. Berlin resigned his rabbinate and, to end the dispute, went to London where he died a few months later. In a letter found in his pocket, he warned everybody against looking into his papers, requesting that they be sent to his father. He expressed the wish to be buried not in a cemetery, but in some lonely spot, and in the same garments in which he died.

242:

to be the author of the two responsa concerning the modification of the ceremonial laws, especially of such that were apparently especially burdensome to the Berlin youth. For instance, it gives permission to Jewish men to shave their beards (No. 18), to drink non-kosher wine, "yayin nesek" (No. 36), and to continue traveling on Friday night if one is in the middle of a journey and can't stop before

183:

171:, where Raphael was chief rabbi, the work and its author was placed under the ban. The dispute that then arose concerning the validity of the ban turned entirely on the question of whether a personal element, like the attack upon the rabbi of Altona, justified such a punishment. Some Polish rabbis supported the ban, while some declared the ban invalid as did

163:

Talmudist, and had considered it their duty to print it and submit it to the judgment of specialists. To secure the anonymity more thoroughly, Berlin and his father were named among those who were to pass upon it. Berlin's statements, especially his personal attacks against those he disagreed with, undermined his cause. When it reached

316:

241:

in a responsum written in Cairo in 1950. Yosef would later also write a haskamah for the 1984 edition of

Besamim Rosh. Ovadia Yosef was aware that the work was considered a forgery but determined that there were valuable teachings in it which were of use in deciding Jewish law. Berlin is also alleged

236:

and its commands can not be gained directly from it or from tradition, but only by means of the philosophico-logical training derived from non-Jewish sources. However, Asher ben Jehiel had condemned the study of philosophy and even of the natural sciences as being un-Jewish and pernicious (compare

231:

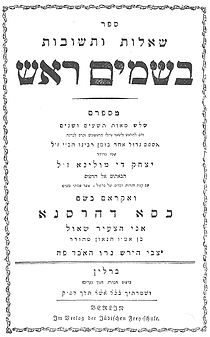

wrote an approbation. Berlin said that the work "Besamim Rosh" had been compiled from Asher ben Jehiel's writings in the sixteenth century by Isaac de Molina. Some responsa that arouse suspicion in the work are, for instance, responsum No. 251, that states an insight into the principles of the

162:

Under the name "Ovadiah b. Baruch of Poland," Berlin attempted in this work to ridicule

Talmudic science, and to stigmatize one of its foremost exponents not only as ignorant, but also as dishonest. The publishers declared in the preface that they had received the work from a traveling Polish

226:

attributed to Asher ben Jehiel of the thirteenth century, but which is widely considered a forgery composed by Saul Berlin himself. Besamim Rosh was first published in Berlin in 1793. Berlin added glosses and comments that he called "Kassa de-Harsna" (Fish Fare).

259:

The exact historicity of "Besamim Rosh" is still disputed, with it being unclear which parts are forgeries. The

Besamim Rosh was reprinted in 1881 and 1984, but some of the texts considered most controversial were removed from the later printings of the work.

127:

warmly defended in his own contention with the rabbis while pleading for German education among the Jews. Berlin used humor to describe what he viewed as the absurd methods of the Jewish schools, and alleges how the rabbinic

195:. Berlin said that the work "Besamim Rosh" had been compiled from Asher ben Jehiel's writings in the sixteenth century by Isaac de Molina. However, rabbinic critics of his day suspected that Berlin had forged the work.

190:

Before the excitement over this affair had subsided, Berlin created a new sensation by another work. In 1793 he published in Berlin, under the title "Besamim Rosh" (Incense of Spices), 392 responsa purporting to be by

159:. The latter, one of the most zealous advocates of rabbinic piety, was a rival candidate with Levin for the Berlin rabbinate, which induced Levin's son to represent ha-Kohen as a forbidding example of rabbinism.

409:

Fishman, Talya (1998). "Forging Jewish Memory: Besamim Rosh and the

Invention of Pre-Emancipation Jewish Culture". In Carlebach, E.; Efron, J.; Meyers, D. (eds.).

256:

later wrote that it was prohibited to keep the

Besamim Rosh in one's home and it was permitted to burn it even on a Yom Kippur that falls on Sabbath.

290:

Jost, Gesch. des

Judenthums und Seiner Sekten, iii. 396-400 (curiously enough a defense of the authenticity of the responsa collection Besamim Rosh);

248:. Berlin aroused a storm of indignation from authorities who accused him of fraudulently using the name of one of the most famous rabbis of the

132:—which then constituted the greater part of the curriculum—injures the sound common sense of the pupils and deadens their noblest aspirations.

420:

488:

366:

355:

Anafim : proceedings of the

Australasian Jewish Studies Forum held at Mandelbaum House, University of Sydney, 8-9 February 2004

503:

179:

and a near relation of Berlin. Even the former censured Berlin's actions after circumstances forced him to acknowledge authorship.

513:

518:

103:(where he frequently went to visit his father-in-law), he came into personal contact with the representatives of the

58:

498:

334:

353:

299:

Zunz, Ritus, pp. 226–228, who thinks that Isaac

Satanow had a part in the fabrication of the responsa.

508:

272:

Benet, in

Literaturblatt des Orients, v. 53-55, 140-141 (fragment of his above-mentioned letter to Levin);

390:

309:

81:

483:

478:

144:

104:

329:

493:

253:

416:

362:

70:

192:

80:

Saul Berlin was ordained as a rabbi at age 20. By 1768, aged 28, he had a rabbinic post in

228:

215:

164:

124:

325:

196:

172:

54:

437:

472:

320:

156:

74:

35:

238:

148:

249:

85:

458:

129:

412:

Jewish

History and Jewish Memory: Essays in Honor of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

391:"Benefits of the Internet: Besamim Rosh and its History – The Seforim Blog"

182:

223:

319: This article incorporates text from a publication now in the

244:

200:

168:

100:

89:

42:

361:. Australia: Mandelbaum Publishing, University of Sydney. p. 5.

176:

96:

66:

62:

38:

31:

27:

115:

Berlin began his literary career with an anonymous circular letter,

410:

233:

123:) (printed in Berlin, 1794, after the death of the author), which

88:. He married Sarah, the daughter of Rabbi Joseph Jonas Fränkel of

41:

scholar who published a number of works in opposition to rabbinic

53:

He received his general education principally from his father,

65:. Saul, the eldest son, was given an education in both the

296:

M. Straschun, in Fuenn, Kiryah Neemanah, pp. 295–298;

275:

Brann, in the Grätz Jubelschrift, 1887, pp. 255–257;

293:

Landshuth, Toledot Anshe ha-Shem, pp. 84–106, 109;

287:

Horwitz, in Kebod ha-Lebanon, x., part 4, pp. 2–9;

199:

first attempted to prevent the printing of the book in

107:, and became one of its most enthusiastic adherents.

278:Carmoly, Ha-'Orebim u-Bene Yonah, pp. 39–41;

384:

382:

380:

378:

269:Azulai, Shem ha-Gedolim, ed. Wilna, ii. 20, 21;

139:(two place-names in Jos. 15:38; by way of pun

404:

402:

400:

252:to combat rabbinism. The Sochatchover Rebbe,

8:

222:; lit."Choice Spices") is a work of legal

284:Grätz, Gesch. der Juden, xi. 89, 151-153;

438:"Four Methods of Ovadia Yosef (in Heb.)"

181:

143:"Superseder of Yekutiel") (published by

344:

281:Chajes, Minḥat Kenaot, pp. 14, 21;

151:, Berlin, 1789), a polemic against the

135:He later wrote the pseudonymous work,

7:

219:

73:, eventually became Chief Rabbi of

69:and secular subjects. His brother,

14:

459:"Besamim Rosh – The Seforim Blog"

389:Rabinowitz, Dan; Brodt, Eliezer.

328:; et al., eds. (1901–1906).

57:, who had served as rabbi of the

338:. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

314:

264:Jewish Encyclopedia bibliography

1:

310:Saul Berlin - Heretical Rabbi

30:– November 16, 1794 in

84:in the Prussian province of

535:

489:18th-century German rabbis

26:after his father; 1740 at

186:Besamim Rosh, Berlin 1793

59:Great Synagogue of London

415:. UPNE. pp. 70–88.

16:German rabbi (1740–1794)

352:Apple, Raymond (2006).

335:The Jewish Encyclopedia

147:and his brother-in-law

187:

61:and as chief rabbi of

514:Forgery controversies

185:

82:Frankfort-on-the-Oder

445:Yaacov Herzog Center

105:Jewish Enlightenment

519:Literary forgeries

504:People from Głogów

254:Avrohom Bornsztain

188:

422:978-0-87451-871-9

175:, chief rabbi of

145:David Friedländer

141:Mitzpah Yekutiel,

71:Solomon Hirschell

526:

463:

462:

455:

449:

448:

442:

433:

427:

426:

406:

395:

394:

386:

373:

372:

360:

349:

339:

318:

317:

221:

193:Asher ben Jehiel

534:

533:

529:

528:

527:

525:

524:

523:

469:

468:

467:

466:

457:

456:

452:

440:

436:Lau, Binyamin.

435:

434:

430:

423:

408:

407:

398:

388:

387:

376:

369:

358:

351:

350:

346:

326:Singer, Isidore

324:

315:

306:

266:

229:Yehezkel Landau

209:

137:Mitzpeh Yokt'el

125:Hartwig Wessely

113:

51:

17:

12:

11:

5:

532:

530:

522:

521:

516:

511:

506:

501:

499:Pseudepigraphy

496:

491:

486:

481:

471:

470:

465:

464:

450:

428:

421:

396:

374:

367:

343:

342:

341:

340:

330:"Berlin, Saul"

312:

305:

302:

301:

300:

297:

294:

291:

288:

285:

282:

279:

276:

273:

270:

265:

262:

208:

205:

197:Mordecai Benet

173:Ezekiel Landau

153:Torat Yekutiel

112:

109:

55:Hirschel Levin

50:

47:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

531:

520:

517:

515:

512:

510:

509:Silesian Jews

507:

505:

502:

500:

497:

495:

492:

490:

487:

485:

482:

480:

477:

476:

474:

460:

454:

451:

446:

439:

432:

429:

424:

418:

414:

413:

405:

403:

401:

397:

392:

385:

383:

381:

379:

375:

370:

368:9780646469591

364:

357:

356:

348:

345:

337:

336:

331:

327:

322:

321:public domain

313:

311:

308:

307:

303:

298:

295:

292:

289:

286:

283:

280:

277:

274:

271:

268:

267:

263:

261:

257:

255:

251:

247:

246:

240:

235:

230:

225:

217:

213:

206:

204:

202:

198:

194:

184:

180:

178:

174:

170:

166:

160:

158:

157:Raphael Cohen

154:

150:

146:

142:

138:

133:

131:

126:

122:

121:Written Truth

118:

110:

108:

106:

102:

98:

93:

91:

87:

83:

78:

76:

75:Great Britain

72:

68:

64:

60:

56:

48:

46:

44:

40:

37:

33:

29:

25:

24:Saul Hirschel

21:

453:

444:

431:

411:

354:

347:

333:

258:

243:

239:Ovadia Yosef

212:Besamim Rosh

211:

210:

207:Besamim Rosh

189:

161:

152:

140:

136:

134:

120:

117:Katuv Yosher

116:

114:

94:

79:

52:

23:

19:

18:

484:1794 deaths

479:1740 births

250:Middle Ages

86:Brandenburg

20:Saul Berlin

494:Talmudists

473:Categories

447:. netu'im.

304:References

49:Early life

220:בשמים ראש

130:casuistry

224:Responsa

34:) was a

323::

245:Shabbat

201:Austria

169:Hamburg

101:Breslau

90:Breslau

43:Judaism

419:

365:

216:Hebrew

177:Prague

165:Altona

111:Career

97:Berlin

67:Talmud

63:Berlin

39:Jewish

36:German

32:London

28:Glogau

22:(also

441:(PDF)

359:(PDF)

234:Torah

149:Itzig

417:ISBN

363:ISBN

167:and

99:and

155:of

95:In

475::

443:.

399:^

377:^

332:.

218::

92:.

77:.

45:.

461:.

425:.

393:.

371:.

214:(

119:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.