108:

443:

685:

183:

attempted to control them with strict rules—applying his "musical conscience", as he called it. In this sense, he was both a progressive and a conservative composer. The whole tone and octatonic scales were both considered adventurous in the

Western classical tradition, and Rimsky-Korsakov's use of them made his harmonies seem radical. Conversely, his care about how or when in a composition he used these scales made him seem conservative compared with later composers like

199:

718:

Maes, in reviewing

Mussorgsky's scores, wrote that Rimsky-Korsakov allowed his "musical conscience" to dictate his editing, and he changed or removed what he considered musical over-experimentation or poor form. Because of this, Rimsky-Korsakov has been accused of pedantry in "correcting", among other things, matters of harmony. Rimsky-Korsakov may have foreseen questions over his efforts when he wrote,

430:

in these works often lacks dramatic power, a seemingly fatal flaw in an operatic composer. This may have been consciously done, as he repeatedly stated in his scores that he felt operas were first and foremost musical works rather than mainly dramatic ones. Ironically, the operas succeed in most cases by being deliberately non-dramatic.

31:

439:

in a painting or events reported through another non-musical source. The second category of works are more academic, such as his First and Third

Symphonies and his Sinfonette. In these, Rimsky-Korsakov still employed folk themes; however, he subjected these them to abstract rules of musical composition.

722:

If

Mussorgsky's compositions are destined to live unfaded for fifty years after their author's death (when all his works will become the property of any and every publisher), such an archeologically accurate edition will always be possible, as the manuscripts went to the Public Library on leaving me.

717:

More debatable, according to Maes, is Rimsky-Korsakov's editing of

Mussorgsky's works. After Mussorgsky's death in 1881, Rimsky-Korsakov revised and completed several of Mussorgsky's works for publication and performance, helping to spread Mussorgsky's works throughout Russia and to the West. However

713:

cite an analysis of

Borodin's manuscripts by musicologist Pavel Lamm, which showed that Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov discarded nearly 20 percent of Borodin's score. According to Maes, the result is more a collaborative effort by all three composers than a true representation of Borodin's intent. Lamm

438:

The purely orchestral works fall into two categories. The best-known ones in the West and perhaps the finest in overall quality are mainly programmatic in nature—in other words, the musical content and how it is handled in the piece is determined by the plot or characters in a story, the action

291:

While Rimsky-Korsakov is best known in the West for his orchestral works, his operas are more complex, offering a wider variety of orchestral effects than in his instrumental works and fine vocal writing. Excerpts and suites from them have proved as popular in the West as the purely orchestral works.

650:

Rimsky-Korsakov's editing of works by The Five are significant. It was a practical extension of the collaborative atmosphere of The Five during the 1860s and 1870s, when they heard each other's compositions in progress and worked on them together, and was an effort to save works that would otherwise

585:

Rimsky-Korsakov taught theory and composition to 250 students over his 35-year tenure at the Saint

Petersburg Conservatory, "enough to people a whole 'school' of composers." This does not include pupils at the two other schools where he taught, including Glazunov, or those he taught privately at his

429:

wrote that the operas "open up a delightful new world, the world of the

Russian East, the world of supernaturalism and the exotic, the world of Slavic pantheism and vanished races. Genuine poetry suffuses them, and they are scored with brilliance and resource." Nevdertheless, Rimsky-Korsakov's music

517:

pale compared to the luxuriance of the more popular works of the 1880s. While a principle of highlighting "primary hues" of instrumental color remained in place, it was augmented in the later works by a sophisticated cachet of orchestral effects, some gleaned from other composers including Wagner,

636:

Rimsky-Korsakov felt talented students needed little formal dictated instruction. His teaching method included distinct steps: show the students everything needed in harmony and counterpoint; direct them in understanding the forms of composition; give them a year or two of systematic study in the

777:

world of folk rites. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that his interest in these songs was heightened by his study of them while compiling his folk song collections. He wrote that he "was captivated by the poetic side of the cult of sun-worship, and sought its survivals and echoes in both the tunes and the

641:

remembered that Rimsky-Korsakov began the first class of the term by saying, "I will speak, and you will listen. Then I will speak less, and you will start to work. And finally I will not speak at all, and you will work." Malko added that his class followed exactly this pattern. "Rimsky-Korsakov

541:

Rimsky-Korsakov's non-programmic music, though well-crafted, do not come up to the same level of inspiration; he needed fantasy to bring out the best in him. The First

Symphony follows the outlines of Schumann's Fourth extremely closely and is slighter in its thematic material than what he would

422:

Of this range Rimsky-Korsakov wrote in 1902, "In every new work of mine I am trying to do something that is new for me. On the one hand, I am pushed on by the thought that in this way, will retain freshness and interest, but at the same time I am prompted by my pride to think that many facets,

182:

Rimsky-Korsakov maintained an interest in harmonic experiments and continues exploring new idioms throughout his career. However, he tempered this interest with an abhorrence of excess and kept his tendency to experiment under constant control. The more radical his harmonies became, the more he

778:

words of the songs. The pictures of the ancient pagan period and spirit loomed before me, as it then seemed, with great clarity, luring me on with the charm of antiquity. These occupations subsequently had a great influence in the direction of my own activity as a composer".

152:

Rimsky-Korsakov was open about the influences in his music, telling Vasily

Yastrebtsev, "Study Liszt and Balakirev more closely, and you'll see that a great deal in me is not mine". He followed Balakirev in his use of the whole tone scale, treatment of folk songs and musical

558:

and piano music. While the piano music is relatively inimportant, many of the art songs possess a delicate beauty. While they yield in overy lyricism to Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, otherwise they reserve their place in the standard repertory of Russian singers.

709:, Rimsky-Korsakov edited and orchestrated the existing fragments of the opera while Glazunov composed and added missing parts, including most of the third act and the overture. This was exactly what Rimsky-Korsakov stated in his memoirs. However, both Maes and

727:

Maes stated that time proved Rimsky-Korsakov correct when it came to posterity's re-evaluation of Mussorgsky's work. Mussorgsky's musical style, once considered unpolished, is now admired for its originality. While Rimsky-Korsakov's arrangement of

637:

development of technique, exercises in free composition and orchestration; instill a good knowledge of the piano. Once these were properly completed, studies would be over. He carried this attitude into his conservatory classes. Conductor

773:", which were written for specific ritual occasions. The ties to folk culture was what interested him most in folk music, even in his days with The Five; these songs formed a part of rural customs, echoed old Slavic paganism, and the

453:

Program music came naturally to Rimsky-Korsakov. To him, "even a folk theme has a program of sorts." He composed the majority of his orchestral works in this genre at two periods of his career—at the beginning, with

265:

748:

Rimsky-Korsakov may have saved the most personal side of his creativity for his approach to Russian folklore. Folklorism as practiced by Balakirev and the other members of The Five had been based largely on the

331:

723:

For the present, though, there was need of an edition for performances, for practical artistic purposes, for making his colossal talent known, and not for the mere studying of his personality and artistic sins.

505:

Where Rimsky-Korsakov changed between these two sets of works was in orchestration. While his pieces were always celebrated for their imaginative use of instrumental forces, the sparer textures of

220:

518:

but many invented by himself. As a result, these works resemble brightly colored mosaics, striking in their own right and often scored with a juxtaposition of pure orchestral groups. The final

137:, possibly his best known work. He proved a prolific composer but also a perpetually self-critical one. He revised every orchestral work up to and including his Third Symphony—some, like

256:

179:

do demonstrate his originality. He developed both these compositional devices for the "fantastic" sections of his operas, which depicted magical or supernatural characters and events.

244:

714:

stated that because of the extremely chaotic state of Borodin's manuscripts, a modern alternative to Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov's edition would be extremely difficult to complete.

264:

211:

303:

which has often been heard by itself in orchestral programs, and in countless arrangements and transcriptions, most famously in a piano version made by Russian composer

681:

three times—in 1869–70, 1892 and 1902. While not a member of The Five himself, Dargomyzhsky was closely associated with the group and shared their musical philosophy.

102:

1314:

1156:

1134:

1109:

859:

219:

157:

and Liszt for harmonic adventurousness. (The violin melody used to portray Scheherazade is very closely related to its counterpart in Balakirev's symphonic poem

235:

243:

407:

705:

Musicologist Francis Maes wrote that while Rimsky-Korsakov's efforts are laudable, they are also controversial. It was generally assumed that with

474:. Despite the gap between these two periods, the composer's overall approach and the way he used his musical themes remained consistent. Both

76:

Finished writing a draft article? Are you ready to request review of it by an experienced editor for possible inclusion in Knowledge?

542:

compose later. The Third Symphony and Sinfonette each contains a series of variations on less-than-best music that lead to tedium.

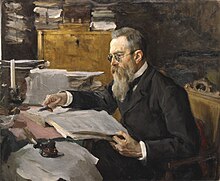

121:

673:

447:

133:

661:, which Rimsky-Korsakov undertook with the help of Glazunov after Borodin's death, and the orchestration of passages from

401:

793:, in which he helped fill out Gogol's story by using folk dances and calendar songs. He went further down this path in

168:

293:

347:

698:

145:, more than once. These revisions range from minor changes of tempo, phrasing and instrumental detail to wholesale

70:

119:

Rimsky-Korsakov followed the musical ideals espoused by The Five. He employed Orthodox liturgical themes in the

272:

563:

513:

507:

313:

298:

730:

678:

667:

736:

693:

595:

146:

107:

697:, which launched the work in the world's opera houses, but has since fallen out of favor. Portrait by

535:

49:

782:

770:

426:

325:

304:

761:

elaborated lyric song. The characteristics of this song exhibit extreme rhythmic flexibility, an

734:

is still the version generally performed, Rimsky-Korsakov's other revisions, like his version of

626:

607:

159:

127:

789:, became Rimsky-Korsakov's pantheistic bible. The composer first applied Afanasyev's ideas in

652:

603:

531:

651:

either have languished unheard or become lost entirely. This work included the completion of

710:

688:

619:

599:

172:

642:

explained everything so clearly and simply that all we had to do was to do our work well."

630:

587:

569:

442:

395:

184:

176:

40:

684:

611:

591:

112:

482:

use a robust "Russian" theme to portray the male progagonists (the title character in

307:. Other selections familiar to listeners in the West are "Dance of the Tumblers" from

638:

555:

319:

66:

44:

17:

781:

Rimsky-Korsakov's interest in pantheism was whetted by the folkloristic studies of

623:

171:.) Nevertheless, while he took Glinka and Liszt as his harmonic models, his use of

662:

263:

242:

218:

657:

154:

250:

Arrangement for two pianos by Russel Warner, performed by Neal and Nancy O'Doan

615:

385:

283:

590:. Apart from Glazunov and Stravinsky, students who later found fame included

534:

patterns. Meanwhile, another pattern alternates with chromatic scales in the

317:, and "Song of the Indian Guest" (or, less accurately, "Song of India") from

52:. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is

774:

671:

for its first production in 1869. He also completely orchestrated the opera

375:

271:

1929 recording of transcription for violin and piano, featuring violinist

762:

551:

527:

562:

Rimsky-Korsakov also wrote a body of choral works, both secular and for

758:

574:

389:

332:

The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya

683:

441:

106:

423:

devices, moods and styles, if not all, should be with my reach."

491:

490:) and a more sinuous "Eastern" theme for the female ones (the

25:

797:, where he made extensive use of seasonal calendar songs and

526:

is a prime example of this scoring. The theme is assigned to

187:, though they were often building on Rimsky-Korsakov's work.

197:

691:

was a powerful exponent of the Rimsky-Korsakov version of

530:

playing in unison, and is accompanied by a combination of

566:

service. The latter include settings of portions of the

538:

and a third pattern of rhythms is played by percussion.

79:

59:

769:, however, Rimsky-Korsakov was increasingly drawn to "

765:

phrase structure and tonal ambiguity. After composing

740:, have been replaced by Mussorgsky's original.

622:. Other students included the music critic and

103:List of compositions by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

946:

944:

292:The best-known of these excerpts is probably "

8:

48:. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's

1122:

1120:

980:

978:

831:

829:

801:(ceremonial dances) in the folk tradition.

167:follows the design and plan of Balakirev's

1268:

1266:

1264:

1262:

1260:

1258:

1256:

1254:

1213:

1211:

1088:

1086:

930:

928:

827:

825:

823:

821:

819:

817:

815:

813:

811:

809:

1280:

1278:

909:

907:

905:

847:

845:

787:The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs

338:The Operas fall into several categories:

1313:was invoked but never defined (see the

1155:was invoked but never defined (see the

1133:was invoked but never defined (see the

1108:was invoked but never defined (see the

858:was invoked but never defined (see the

805:

111:Portrait of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov by

281:

757:literally meant "drawn-out song", or

7:

1305:

1147:

1125:

1100:

850:

550:Rimsky-Korsakov composed dozens of

311:, "Procession of the Nobles" from

282:Problems playing these files? See

24:

446:Opening themes of the Sultan and

169:Second Overture on Russian Themes

261:

240:

216:

122:Russian Easter Festival Overture

58:Create or edit your own sandbox

29:

1021:The New Grove Russian Masters 2

785:. That author's standard work,

554:, arrangements of folk songs,

1:

81:Submit your draft for review!

646:Editing the work of The Five

257:The Song of the Indian Guest

149:and complete recomposition.

1045:Morrison, 116–117, 168–169.

498:and the title character in

294:The Flight of the Bumblebee

236:The Flight of the Bumblebee

54:not an encyclopedia article

1346:

100:

462:, and in the 1880s, with

323:, as well as suites from

229:performed by US Army Band

1034:Studies in Russian Music

165:Russian Easter Overtures

564:Russian Orthodox Church

472:Russian Easter Overture

408:The Tale of Tsar Saltan

299:The Tale of Tsar Saltan

227:Flight of the Bumblebee

212:Flight of the Bumblebee

744:Folklore and pantheism

731:Night on Bald Mountain

725:

702:

679:Alexander Dargomyzhsky

450:

417:Stylistic experiments.

202:

116:

720:

687:

596:Alexander Spendiaryan

573:(despite his staunch

445:

402:Kashchey the Immortal

201:

110:

1309:The named reference

1151:The named reference

1129:The named reference

1104:The named reference

854:The named reference

783:Alexander Afanasyev

629:, and the composer

546:Smaller-scale works

427:Harold C. Schonberg

326:The Golden Cockerel

305:Sergei Rachmaninoff

131:and orientalism in

703:

627:Alexander Ossovsky

608:Witold Maliszewski

468:Capriccio Espagnol

451:

203:

128:Capriccio Espagnol

117:

1293:Rimsky-Korsakov,

1235:Rimsky-Korsakov,

1192:Rimsky-Korsakov,

1076:Rimsky-Korsakov,

699:Aleksandr Golovin

653:Alexander Borodin

604:Ottorino Respighi

343:Historical drama.

266:

245:

221:

89:

88:

65:Other sandboxes:

63:

1337:

1329:

1326:

1320:

1319:

1318:

1312:

1304:

1298:

1291:

1285:

1282:

1273:

1270:

1249:

1246:

1240:

1233:

1227:

1224:

1218:

1215:

1206:

1203:

1197:

1190:

1184:

1177:

1171:

1168:

1162:

1161:

1160:

1154:

1146:

1140:

1139:

1138:

1132:

1124:

1115:

1114:

1113:

1107:

1099:

1093:

1090:

1081:

1074:

1068:

1065:

1059:

1052:

1046:

1043:

1037:

1030:

1024:

1017:

1011:

1008:New Grove (1980)

1004:

998:

995:

989:

986:New Grove (1980)

982:

973:

970:New Grove (2001)

968:Frolova-Walker,

966:

960:

957:

951:

948:

939:

936:New Grove (1980)

932:

923:

920:

914:

911:

900:

899:Yastrebtsev, 37.

897:

891:

884:

878:

871:

865:

864:

863:

857:

849:

840:

837:New Grove (2001)

835:Frolova-Walker,

833:

711:Richard Taruskin

689:Fyodor Chaliapin

668:William Ratcliff

620:Konstanty Gorski

600:Sergei Prokofiev

486:; the sultan in

434:Orchestral works

348:The Tsar's Bride

268:

267:

247:

246:

223:

222:

200:

177:octatonic scales

85:

84:

82:

71:Template sandbox

57:

33:

32:

26:

1345:

1344:

1340:

1339:

1338:

1336:

1335:

1334:

1333:

1332:

1327:

1323:

1310:

1308:

1306:

1301:

1295:My Musical Life

1292:

1288:

1283:

1276:

1271:

1252:

1247:

1243:

1237:My Musical Life

1234:

1230:

1225:

1221:

1216:

1209:

1204:

1200:

1194:My Musical Life

1191:

1187:

1178:

1174:

1169:

1165:

1152:

1150:

1148:

1143:

1130:

1128:

1126:

1118:

1105:

1103:

1101:

1096:

1091:

1084:

1078:My Musical Life

1075:

1071:

1067:Schonberg, 365.

1066:

1062:

1053:

1049:

1044:

1040:

1031:

1027:

1018:

1014:

1005:

1001:

996:

992:

983:

976:

967:

963:

958:

954:

950:Schonberg, 364.

949:

942:

933:

926:

922:Maes, 180, 195.

921:

917:

912:

903:

898:

894:

885:

881:

872:

868:

855:

853:

851:

843:

834:

807:

795:The Snow Maiden

746:

674:The Stone Guest

648:

631:Lazare Saminsky

588:Igor Stravinsky

583:

570:John Chrysostom

568:Liturgy of St.

548:

436:

396:The Snow Maiden

309:The Snow Maiden

289:

288:

280:

278:

277:

276:

275:

269:

262:

259:

253:

252:

251:

248:

241:

238:

232:

231:

230:

224:

217:

214:

208:

204:

198:

193:

185:Igor Stravinsky

125:, folk song in

105:

99:

94:

80:

78:

77:

75:

74:

30:

22:

21:

20:

12:

11:

5:

1343:

1341:

1331:

1330:

1321:

1299:

1286:

1274:

1250:

1241:

1228:

1219:

1207:

1205:Maes, 182–183.

1198:

1185:

1172:

1163:

1141:

1116:

1094:

1082:

1069:

1060:

1047:

1038:

1025:

1012:

999:

997:Maes, 82, 175.

990:

974:

961:

959:Maes, 176–180.

952:

940:

924:

915:

901:

892:

879:

866:

841:

804:

803:

771:calendar songs

759:melismatically

745:

742:

647:

644:

612:Mykola Lysenko

592:Anatoly Lyadov

586:home, such as

582:

579:

547:

544:

435:

432:

420:

419:

413:

412:

381:

380:

367:

366:

360:

359:

353:

352:

279:

270:

260:

255:

254:

249:

239:

234:

233:

225:

215:

210:

209:

206:

205:

196:

195:

194:

192:

189:

113:Valentin Serov

101:Main article:

98:

95:

93:

90:

87:

86:

55:

36:

34:

23:

15:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1342:

1325:

1322:

1316:

1303:

1300:

1296:

1290:

1287:

1281:

1279:

1275:

1269:

1267:

1265:

1263:

1261:

1259:

1257:

1255:

1251:

1245:

1242:

1238:

1232:

1229:

1223:

1220:

1214:

1212:

1208:

1202:

1199:

1195:

1189:

1186:

1182:

1176:

1173:

1167:

1164:

1158:

1145:

1142:

1136:

1123:

1121:

1117:

1111:

1098:

1095:

1089:

1087:

1083:

1079:

1073:

1070:

1064:

1061:

1057:

1051:

1048:

1042:

1039:

1035:

1029:

1026:

1022:

1016:

1013:

1009:

1003:

1000:

994:

991:

987:

981:

979:

975:

971:

965:

962:

956:

953:

947:

945:

941:

937:

931:

929:

925:

919:

916:

910:

908:

906:

902:

896:

893:

889:

883:

880:

876:

870:

867:

861:

848:

846:

842:

838:

832:

830:

828:

826:

824:

822:

820:

818:

816:

814:

812:

810:

806:

802:

800:

796:

792:

788:

784:

779:

776:

772:

768:

764:

760:

756:

752:

743:

741:

739:

738:

737:Boris Godunov

733:

732:

724:

719:

715:

712:

708:

700:

696:

695:

694:Boris Godunov

690:

686:

682:

680:

677:

675:

670:

669:

664:

660:

659:

654:

645:

643:

640:

639:Nikolai Malko

634:

632:

628:

625:

621:

617:

613:

609:

605:

601:

597:

593:

589:

580:

578:

576:

572:

571:

565:

560:

557:

553:

545:

543:

539:

537:

533:

529:

525:

521:

516:

515:

510:

509:

503:

501:

497:

494:Gul-Nazar in

493:

489:

485:

481:

477:

473:

469:

465:

461:

457:

449:

444:

440:

433:

431:

428:

424:

418:

415:

414:

410:

409:

404:

403:

398:

397:

392:

391:

387:

383:

382:

378:

377:

372:

369:

368:

365:

362:

361:

358:

357:Gogol operas.

355:

354:

350:

349:

344:

341:

340:

339:

336:

334:

333:

328:

327:

322:

321:

316:

315:

310:

306:

302:

300:

295:

287:

285:

274:

258:

237:

228:

213:

207:Music samples

190:

188:

186:

180:

178:

174:

170:

166:

162:

161:

156:

150:

148:

147:transposition

144:

140:

136:

135:

130:

129:

124:

123:

114:

109:

104:

96:

91:

83:

73:

72:

68:

61:

53:

51:

47:

46:

42:

35:

28:

27:

19:

18:User:Jonyungk

1324:

1307:Cite error:

1302:

1294:

1289:

1244:

1236:

1231:

1222:

1201:

1193:

1188:

1180:

1175:

1166:

1149:Cite error:

1144:

1127:Cite error:

1102:Cite error:

1097:

1077:

1072:

1063:

1055:

1050:

1041:

1033:

1028:

1020:

1015:

1007:

1002:

993:

985:

969:

964:

955:

935:

918:

895:

887:

882:

874:

869:

852:Cite error:

836:

798:

794:

790:

786:

780:

766:

763:asymmetrical

755:Protyazhnaya

754:

753:dance song.

751:protyazhnaya

750:

747:

735:

729:

726:

721:

716:

706:

704:

692:

672:

666:

656:

649:

635:

624:musicologist

584:

567:

561:

549:

540:

524:Scheherazade

523:

519:

512:

506:

504:

500:Scheherezade

499:

495:

488:Scheherezade

487:

483:

480:Scheherezade

479:

475:

471:

467:

464:Scheherezade

463:

459:

455:

452:

448:Scheherazade

437:

425:

421:

416:

406:

400:

394:

384:

374:

371:Folk operas.

370:

363:

356:

346:

342:

337:

330:

324:

318:

312:

308:

297:

290:

273:Váša Příhoda

226:

181:

164:

163:, while the

158:

151:

142:

138:

134:Scheherazade

132:

126:

120:

118:

97:Compositions

67:Main sandbox

64:

38:

1010:, 16:32–33.

775:pantheistic

707:Prince Igor

658:Prince Igor

386:Fairy tales

155:orientalism

1328:Maes, 188.

1311:ReferenceB

1297:, 165–166.

1272:Maes, 187.

1248:Maes, 115.

1226:Maes, 181.

1217:Maes, 183.

1179:Taruskin,

1170:Maes, 182.

1092:Malko, 49.

1056:Stravinsky

1054:Taruskin,

913:Maes, 180.

890:, 197–198.

616:Artur Kapp

284:media help

173:whole tone

1315:help page

1284:Maes, 65.

1157:help page

1135:help page

1110:help page

1032:Abraham,

1019:Abraham,

1006:Abraham,

984:Abraham,

972:, 21:405.

934:Abraham,

886:Abraham,

873:Abraham,

860:help page

839:, 21:409.

799:khorovodi

791:May Night

767:May Night

663:César Cui

655:'s opera

552:art songs

536:woodwinds

528:trombones

376:May Night

50:user page

39:the user

1153:mfw21401

1131:abng1628

1058:, 1:163.

988:, 16:33.

938:, 16:32.

888:Slavonic

875:Slavonic

581:Students

470:and the

45:Jonyungk

37:This is

1106:maes171

856:maes175

575:atheism

556:chamber

390:legends

296:" from

69:|

41:sandbox

1239:, 249.

1196:, 283.

1183:, 185.

877:, 197.

618:, and

532:string

364:Epics.

191:Operas

160:Tamara

115:(1898)

92:Legacy

1181:Music

1080:, 34.

1036:, 288

1023:, 27.

520:tutti

514:Antar

508:Sadko

496:Antar

484:Antar

476:Antar

460:Antar

456:Sadko

320:Sadko

314:Mlada

143:Sadko

139:Antar

16:<

511:and

492:peri

478:and

458:and

405:and

388:and

329:and

175:and

141:and

60:here

676:by

665:'s

577:).

522:of

502:).

43:of

1317:).

1277:^

1253:^

1210:^

1159:).

1137:).

1119:^

1112:).

1085:^

977:^

943:^

927:^

904:^

862:).

844:^

808:^

633:.

614:,

610:,

606:,

602:,

598:,

594:,

466:,

411:).

399:,

379:),

335:.

56:.

701:.

393:(

373:(

351:)

345:(

301:,

286:.

62:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.