849:

Sureste and Gran Plaza

Suroeste by the excavators. These platforms are similar to those in the Northeast plaza, but they are up against the side of the main pyramid, which was done to amplify the patio's hierarchical and ritual nature. The area was mostly likely used for large, spectacular ceremonies as well as for rites associated with the passing of power. The taluds are wide, which is characteristic of Cholula, and decorated with moldings consisting of T formations. The tableros were painted with aquatic symbols and bands of red, blue, yellow and black. The access to the two main platforms and the side of the pyramid are marked by wide stairs. The Gran Plaza Suroeste shows strong Teotihuacan influence, with four rooms over taluds that surround a patio. One of these rooms contains a model of a pyramid base that may represent the Gran Pyramid in miniature. Excavations have revealed that these annexes were built up in a series of at least six construction phases, enclosing a central courtyard. As new phases of construction took place, newer versions of buildings were built over the pre-existing version, covering the lower part and adding a new or modified facade, resulting in the reduction of the courtyard area by the gradual encroachment of the surrounding structures and added several metres to the original platform height. These are buildings were arranged on the east and west sides of an early 82-metre (270 ft) wide platform. Further structures were built against the rear facades of these buildings, forming two wide side plazas. The buildings that can be seen today date to the latest construction phase of the courtyard. Buildings on this south side contain significant mural work, including patterns on the various constructions associated with Building 3 (Building 3-1-A, Building 3–2, etc.). It also includes the only mural with anthropomorphic figures, called the Mural of the Drinkers.

761:

an adobe nucleus. It was finished with adobe and rock, and smoothed with earth mixed with lime to create a painting surface. The architecture is significant because of its talud-tablero structure, and its mural-decorated walls. This structure was constructed in two phases. The first created a rectangular platform 113 meters by 107 meters. On top of this is a two-story structure, eighteen meters high with stairs on the west. This structure is made of adobe bricks, which stone and clay used in the areas with stairs. Marquina determined that this structure had an east–west orientation, similar to the

Pyramid of the Sun, coinciding with the Teotihuacan civilization, and later ceramic studies placed it with Teotihuacan II. Only the murals of the upper two stories of this pyramid have been studied, on the taluds and tableros of the north side as well as those on the northeast corner. The talud has traces of black and the two-meter tableros consist of a frieze measuring 46 cm wide with a double frame or border that juts out from the frieze. This is characteristic of Cholula architecture. These tableros usually have one color as the base, but with stripes of other colors on top, such as yellow, red and blue. The north side is completely free of paint on the left side, but on the right, there are pockets of color remaining. The highest story contains nine skulls painted on it, which the lower one had seven. These skulls were initially thought to be the heads of grasshoppers facing forward, but later studies determined that they depict highly stylized human skulls. These skulls look forward and are painted yellow and red over a black background. Above the skulls are decorative markers that look like arrows, which indicate the direction of the scene. Those on the left side point east, and those on the right point west. To the sides are stylized wings in red, green and ochre.

958:

level of the

Courtyard of the Altars. The section where this mural work is found consists of a long talud, with a tablero with double moldings, similar to those in Buildings 2, 3, and 4. The mural occupies the tablero, which is topped by a double cornice. The design consists of diagonal bands of various colors such as red, green yellow and blue, outlined in black and white. Some sections contains stars. Building 3-1 was built over the second level of the building containing the Mural of the Drinkers, running north–south, and facing northeast like the older structure. It is one of the oldest borders of the Plaza Sureste and only two sections have been explored. It is sixty meters long but only about thirty is exposed. The visible area divides into three sections, divided by stairways. The upper part of this building, where the stairs lead, has a low talud that supports a frieze topped by a cornice, which juts out. This building contains mural work on a tablero measuring 71 cm by 2.6 meters in length, but there is no evidence of painting on the talud. The first mural consists of horizontal bands in a reddish ochre and a hook like design in red surrounded by an ellipsis in the same tone over a black background. Others consist of diagonal bands of greens and reds bordered and connected by black lines simulating a woven mat, which has led to it being called the "Petatillo" (small palm frond mat). The lower areas have diagonal lines of various colors such as black, green, ochre and red with some lines in white. Some areas have red stars. Mural work on Buildings 3.2 and 4 are similar in their use of multicolored diagonal bands with stars painted in some areas.

954:

due to being the work of different artists. However, all relate to ritualistic drinking of pulque. These figures along the center are then divided into two sections by a blue band seen on walls 3, 4, 5 and 6. There is also evidence that the mural had been retouched several times. The mural contains 110 figures organized into pairs. The pairs are then separated by images of jars. Four can be identified as seated women and some of the figures appear to have wrinkles to depict age. Most of the men in the work are shown seated, facing front (but with faces in profile) with a bulging belly, with arms and legs in various positions, most with cups or other containers in hand to serve or to drink. There are a total of 168 jars, cups and other containers in the mural of various sizes and colors. There is also a depiction of an insect and two of dogs. The people are outlined in black, along with a number of other images. Most have their skin painted in ochre, but some are brown, red or black. Traces of liquid is in white. Some have earrings done in red or blue. However, there are some differences in quality and technique in the work. Section Six is more masterfully done, with the people depicted in masks painted in red and black with some ochre. Dogs and jars with complex designs can also be seen. Scene One is more brusque with far fewer details, mostly done in ochre.

930:

the pre-Hispanic city of

Cholula have reflected the political, economic and social changes over time. They also help to ascertain Cholula's relevance with the rest of Mesoamerica. There have been twenty one painted areas discovered by archaeologists, with eight mostly lost and thirteen still existing in situ. Most of the works belong to the Classic period, excepting those in the Edificio Rojo, which are from the Pre classic. The way that taluds, tableros and other surfaces were painted show changes over time in colors used as representations. The oldest have no representations, just the color red, but after 200 AD, there appear new colors such as different tones of red, as well as green, ochre, blue, black, and brown. Human like figures, animals and geometric shapes begin to appear as well. However, the Mural of the Drinkers is the only preserved mural that depicts human figures. So far, all of the discovered murals have been on outside walls, with the exception of an area called Edificio D (Building D), which has its murals inside. This indicates that most murals were created for the public and probably to teach and reinforce the religious and political symbols of the time. The best conserved murals have been found on the layers inside the main pyramid and in the Courtyard of the Altars, the two most important areas of the site.

1031:("Nine Rain"). She was replaced with an image of the Virgin of the Remedies, keeping the 8 September date for the veneration of the old rain goddess but transferring it to this image of the Virgin Mary. The Spanish built a church to this image on top of the pyramid. This church was struck and damaged by lightning several times, which was attributed in the early colonial period to the old goddess. However, the change allowed the pyramid to keep its sacred nature to this day. The Virgin of the Remedies is the patron of the city of Cholula, and there are two major annual events related to it and the pyramid. The first is 8 September, when thousands come to honor the image, starting on the night of the 7th, when people spend the night with small lanterns so they can greet the image early on the eighth. The other is called the "Bajada" when the image comes down the pyramid to visit the various neighborhoods of the city for two weeks in May and June. Closer to the pyramid's pre-Hispanic roots is the Quetzalcoatl ritual, which is held each year on the spring equinox. This event can draw up to 20,000 visitors, leading authorities to restrict access to the exposed archeological ruins on the south side. The ritual is performed on the pyramid with poetry, indigenous dance and music and fireworks.

811:

surface of earth and lime, this pyramid was finished with rock and stucco, which is more durable. Its architectural style is distinct from the one before. It consists of nine stories with talud only, covered in stucco. Each story above is smaller than below, leaving a space of two meters. The entrance stairs were those on the southeast corner, with those on the other three serving as exits. These walls were painted black with the stucco serving as white. Associated with the

Stepped Pyramid is the Jaguar Altar, which is located on the southeast corner. The west and south sides of the altar's two levels have been explored. There is evidence that this altar was covered in decoration. On the west side of the first level, there is evidence of black, red, green and ochre paint. On the lower part of the south wall, there are fragments of red, black and ochre. Above this, there is a well conserved section of 3.15 m by 53 cm, with a black and green background with red stripes. There are also the profiles of a jaguar and two serpents. (chapter 4 135)

706:

993:

placing them like a mosaic. For this reason, the structure is also referred to as the Piedra

Laborada (Worked Stone) building. Using stone found from both the taluds and the tableros, the archeologists set about reconstructing this structure, using commercially made cement, leading to the structure being called the Tolteca pyramid, after the brand used. This pyramid has since been criticized for being overly reconstructed. The process yielded a large number of ceramics figurines and vessels, which were studied by Florence Müller and range from the Pre Classic to the Postclassic. It has also lost most of its coloration, with only fragments of red, ochre, white and black remaining. The best conserved fragments are on the first level on the south and north where paint was applied directly onto rock. However, it is still difficult to discern the skulls and snails, because they have severely deteriorated.

44:

795:

adobe, decorated with interlocked designs in low relief painted red, yellow and green. The talud is painted black as well as the bottom part of the tablero, with some minor details in ochre. The north side only shows the jaw and eye of a skull and some of the arrow and other effects seen on the pyramid it is associated with. The west side contains two skulls. One conserves about half of the original to see its open mouth and white teeth. The figure is outlined in ochre and black. The other skull contains only traces of these colors. The lower cornice on the north side is divided by horizontal bands, black above and red below. The interior cornice has double bands of green and red. To the extreme west of the painting, there are skull designs.

1047:

travelers. The attraction consists of three parts: the tunnels inside the pyramid, the complex on the south side and the site museum. About eight km of tunnels were dug into the pyramid by archaeologists but only 800 meters are open to the public. The tunnel entrance is on the north side and it goes through the center of the structure. This tour passes by the Mural of the

Drinkers, which is one of the most famous aspects of the site. The structures on the south side are dominated by the Courtyard of the Altars. Separated from the site by the Camino Real road is the site museum, which contains a model of the pyramid's layers, a room dedicated to ceramics and other finds from the site and the recreation of two of the site's murals.

365:

938:

was exploring

Edificio 3-1-A. One of this building's taluds collapsed and exposed a portion of the mural behind it to view. Excavation of this building then continued until 1971. The building's main facade, which faces east towards the Courtyard of the Altars, contains the mural. This work also rescued one of the first foundations of Edificio 3. The foundation is formed by a frieze that measures ninety cm by 2.25 m in the best preserved areas. It was painted over a small talud only sixty cm long. It is possible there was a cornice here above it. The building corresponds to around 200 AD.

520:

745:

Pyramid, but rather under a structure known as the

Edificio Rojo (Red Building) in the northeast corner. This makes the oldest pyramid of the site "off-center" in relation to the later pyramids. It was built with an adobe core with a base of about ten meters square. It has a wall in talud topped with a 57 cm cornice. Over this, a two-story chamber faced south. One side of La Conejera, eight rounded steps made of earth with a stone core lead to the west side of the structure, into a hallway. This bears some resemblance to the rounded pyramid of

93:

65:

749:. From the ceramics found with it, the structure has been dated to about 200 BC, contemporary with sites such as Zacatenco and El Arbolillo in the Valley of Mexico. La Conejera's base, cornice and chamber were all painted. Black paint remains on the base. The cornice on the northwest corner had white squares painted over a black background. Investigators have assumed that this pattern was repeated over the rest of the cornice. Both the outer and inner walls of the chamber were painted red several times with no designs.

86:

665:(200 to 800 AD) and the beginnings of the Post-classic, during the occupation of the Olmecas Xicallancas. These structures were later reconstructed. The most important elements unearthed during this time were the Courtyard of the Altars and Edificio F (Building F). By the official end of the project in 1974, interest in the pyramid waned again as it could not be reconstructed in its entirety, like other major pyramids in Mexico. The project was abandoned, leaving only fragmentary knowledge about it.

58:

320:. This division originates in the Toltec-Chichimeca conquest of the city in the twelfth century. These pushed the former dominant ethnicity of the Olmeca-Xicalanca, to the south of the city. These people kept the pyramid as their primary religious center, but the newly dominant Toltec-Chichimecas founded a new temple to Quetzalcoatl where the San Gabriel monastery is now. The Toltec-Chichimec people who settled in the area around the twelfth century AD named Cholula as

721:

these tunnels are open to the public, which have been made into well-lit, arched passages. Visitors enter on the north side, through the center of the pyramid and exit on the south side. There are few signs explaining the structures within, but in one section allows a view of main staircases of one of the pyramids, whose nine floors have been excavated from bottom to top. There are also two famous murals. One is called "Chapulines," which consists of images of

1039:

922:

836:

127:

1023:

985:

872:

571:, a Swiss-born American archaeologist with an interest in Mexico. He arrived at Cholula in 1881 and published his findings about the site in 1884. Most of Bandelier's work involved the unearthing of various burials in the area around the pyramid, principally collecting skulls, which was standard practice at the time. Many of these wound up in storerooms in U.S. museums.

348:

950:

one vomiting and one defecating. The figures are in vignettes along the strip of wall with the elements evenly distributed along its length. A number of the elements, such as the cups and jars, are associated with the drinking of pulque. It has been claimed by

Florencia Muller that this mural is the oldest known representation of the ritual of the pulque gods.

555:. Some of the pyramid constructions have had burials, with skeletons found in various positions, with many offerings, especially ceramics. The last state of construction has stairs on the west side leading to a temple on top, which faced Iztaccíhuatl. During the colonial period, the pyramid was severely damaged on its north side to build the Camino Real to

609:. These techniques were based on mining, even using small tracks and miniature coal cars to carry out debris. Examples of these are at the site museum. The base of the pyramid was constructed of sun-dried adobe bricks, which contained ceramic, obsidian and gravel for better compacting. This solid foundation allowed the excavators to only need to create "

1051:

Quetzalcoatl Ritual. Certain large fireworks have been banned by the city and the Catholic Church because they cause serious vibrations in the pyramid's tunnels. Some of the land around the pyramid has been bought by authorities and made into soccer fields, and sown with flowers to create a buffer between the construction of homes and the pyramid.

967:

murals on the tableros have no figures on them and the cornices are painted black. The building was constructed over an area, whose interior is covered with stone pieces with red, ochre and green paint over black. This area was filled in because later constructions around it were putting pressure on it and it was in danger of collapse.

272:'s height of 146.6 metres (481 ft), but much wider, measuring 300 by 315 metres (984 by 1,033 ft) in its final form, compared to the Great Pyramid's base dimensions of 230.3 by 230.3 metres (756 by 756 ft). The pyramid is a temple that traditionally has been viewed as having been dedicated to the god

976:

momoztli and contained three burials. The ceramics found with these are similar to those found at the Altar of the Sculpted Skulls, dating the structure as late into Cholula's pre Hispanic period. These two finds show that while the pyramid was in process of abandonment, it had not lost its ritual character.

957:

Other buildings in this area such as the later levels of Building 3 and Building 4, also have mural work, but this mostly consists of geometric patterns, lines or bands and in some places, stars. Building 3-1-A was superimposed over the Mural of the Drinkers at a depth of six meters below the current

949:

sashes, and most of them wear zoomorphic masks. The figures sit in facing pairs, serving themselves from vessels placed between them. The subject of the mural is a ceremony where the participants appear relaxed as they realize various activities, which include drinking, making offerings, serving with

937:

was discovered buried at a depth of almost 7.6 metres (25 ft) and is one of the longest pre-Columbian murals found in Mexico, with a total length of 57 metres (187 ft). The building containing the Mural of the Drinkers was discovered accidentally in 1969 by Ponciano Salazar Ortegón while he

912:

Other large stone sculptures were found in the area. One is the head of a serpent with geometric designs that correspond to the Niuñe tradition in Oaxaca. There is also a giant human head, with the edges of its eyes and mouth marked in a way that resembles Xipe, which could correspond to a post-Olmec

908:

may have been the most important as it is next to the pyramid. It faces south and is similar to Altar 1 as it is a vertical stone. Its shape is that of a rectangle topped by a triangle. Its decoration consists of a lateral band with relieves similar to those of Altar One, that is El Tajín style. When

794:

dog was also found. Pre-Hispanic people considered dogs guides to the underworld. The function of this mausoleum was mostly likely to perpetuate the memory of the male warrior. It has two levels. One is a pyramidal platform and the other is a talud-tablero structure with a double cornice and crest in

1034:

The pyramid site accounts for only six hectares of an archeological heritage site believed to extend over 154 hectares. However, 90 hectares of this land is privately owned, and there is resistance to major archeological exploration. Despite the ancient city's and pyramid's importance to the history

1001:

During the course of excavations of the Great Pyramid over 400 human burials have been uncovered. Most of these burials date to the Postclassic Period, showing that the Great Pyramid was an important centre of worship well after its use as a temple was discontinued. These burials include a number of

953:

The work has parts missing, but there is enough to discern three horizontal sections. The ones above and below are lines or borders framing the main central level containing the drinking figures. The mural divides into six "walls" (muros), which show differences in technique and content, most likely

929:

Painting and mural work was found on various levels of the main pyramid, on the Edificio Rojo, the La Conejera, the Pyramid of the Painted Skulls, the Altar of the Painted Skulls, the Stepped Pyramid, the Jaguar Altar, Edificio D and Edificio F. Studies of the various mural fragments found so far in

768:

in 1937. This building is located in one of the lower levels of the northeast patio area, attached to the base of the Pyramid of the Painted Skulls. The architectural aspects of this altar, however, correspond to the Post classic period. The altar sits on a platform and faces east, in front of which

692:

along with information from the various major sites of the country. However, interest waned in the Cholula site in the 1950s. One reason for this was that, at the time, it was common to reconstruct the major buildings, especially pyramids, even though these reconstructions were often exaggerated. No

639:

The first round of excavation work ended in the 1950s. The second round of excavations took place from 1966 to 1974 under the name of Proyecto Cholula. This was spurred, in part, by reconstructed pyramids in Mexico, which had become tourist attractions. This project was sponsored by both the federal

458:

took over the city, religious focus shifted away from the pyramid and to a new temple. Even during the Postclassic period, long after locals abandoned the pyramid, they continued to bury their deceased around the structure, demonstrating its continued importance. By the time the Spanish arrived, the

1050:

The pyramid's importance has led to a number of measures taken to protect it. The archaeological zone is patrolled by a police equestrian unit from the municipality of San Ándres. This to keep motor vehicles from damaging the site. Access to parts of the site is restricted during events such as the

992:

Building F dates from the next to last building phase of the pyramid, between 500 and 700 AD. It is a stone stairway, consisting of three levels with large taluds facing west. The tableros are decorated with a motif that looks like a woven palm mat. This effect was created by sculpting stones, then

822:

Marquina's first publication about the site in 1939 notes the existence of a Northeast Plaza, which was an unusual find at the time. This plaza contains three pyramid shaped structures in talud-tablero but in extremely poor condition. However, one important find about them was that their bases were

810:

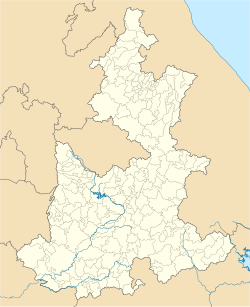

at Teotihuacan. This latter phase was a radial pyramid, with stairways climbing all four sides of the structure. The Pyramid of the Nine Stories was built over the oldest structure using adobe again for expansion to a pyramid with a base of 190 meters squared and a height of 34 meters. Instead of a

760:

or the Pyramid of the Painted Skulls was centered in a spot a few meters from La Conejera. Later expansions of this pyramid eventually covered La Conejera and the Edificio Rojo built over it. The Pyramid of the Painted Skulls was built between 200 and 350 AD, consisting of seven stepped levels with

720:

Excavations have resulted in about eight kilometers of tunnels inside the pyramid, which began with two in 1931 to prove that the hill was an archeological find. Within, altars with offerings, floors, walls and buried human remains from around 900 AD were discovered. Today, only about 800 meters of

696:

Most of the publications that do exist are technical field reports with few syntheses of data gathered. For this reason, it has not played a significant role in the understanding of Mesoamerica as to date. Due to the condition of the surface and the large number of artifacts just under the surface,

664:

The project began to focus on the south side of the pyramid, excavating the remains of plazas and buildings that made up a large complex. However, it was difficult to link these structures to those in the interior of the pyramid. The patios were unearthed in layers as far back as the Classic period

574:

Bandelier also took the first precise measurements of the structure, made some headway into how it was constructed and worked on domestic structures that coincide with the pyramid. He made the first precise field notes at the site and the earliest plan of the site. Bandelier also showed interest in

1030:

The pyramid remains important to modern Cholula as a religious site, an archeological site and a tourist attraction. The site receives about 220,000 visitors each year on average. Just before the arrival of the Spanish, the pyramid was considered sacred to a rain goddess called Chiucnāuhquiyahuitl

966:

Building D is located on the south side of the Pyramid of the Nine Stories. It consists of pyramid like levels of talud-tablero topped with three moldings on the east and two on the west. The levels are rectangles with rounded corners, painted black on three sides with the east side in orange. The

890:

consists of a large vertical stone measuring 3.85 meters in height and 2.12 in width. When it was found, it was in twenty-two pieces. It is known that it was found in situ looking west although its offerings had long since been looted. Shortly after, its base was found. Its purpose is not clear as

1046:

The pyramid is the main tourist attraction in Cholula, receiving 496,518 visitors in 2017. Images of this church on top of the pyramid with Popocatepetl in the background is frequently used in Mexico's promotion of tourism. It is one of the better known destinations in central Mexico for foreign

975:

Building I was unearthed during a brief period of six months at the beginning of the second round of excavation, mostly by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Pablo López Valdéz. This building is located on a platform affixed onto the southwest side of the pyramid. It has four means of access, common to

848:

had begun to touch on this area with his excavation of Edifico I in 1966 and 1967. The structure consists of a very large open area measuring seventy by fifty-four meters, bordered by the pyramid proper to the north, and on the east and west sides by two complicated raised platforms, named Patio

616:

The first two tunnels were built to criss-cross the centre, one north–south and the other east–west. When the tunnels reached substructure, they then followed the contour of the structure, and eventually the various tunnels created an underground labyrinth. By 1939, there were four kilometers of

744:

is the earliest version of the pyramid also called "La Conejera". This structure was discovered in the 1950s, near the end of the first round of excavations. It is a pre-Teotihuacan structure, relatively simple with an adobe core. However, it was not found directly under the other layers of the

660:

In 1967, INAH decided to replace Messmacher with Ignacio Marquina as head of the team excavating the site, which prompted most of the younger researchers to leave the project. While the focus was placed back on the pyramid proper, the project did not lose all of its interdisciplinary character,

527:

The pyramid consists of six superimposed structures, one for each ethnic group that dominated it. However, only three have been studied in any depth. The pyramid itself is just a small part of the greater archaeological zone of Cholula, which is estimated at 154 hectares (0.59 sq mi).

601:

While credit is given to Marquina, he spent little time at the site. Most of the work was really done by Marino Gómez, the site guardian, who directed the digging of the tunnels. These tunnels allowed for the mapping and modelling of the pyramid's successive layers. The pyramid had no obvious

532:

and over time was built over six times to its final dimensions of 300 by 315 metres on each side at the base and 25 metres tall. The base covers a total area of 94,500 square meters (1,016,669 square feet), nearly twice the size of the 53,108 square meter (571,356 square feet) base of Pharaoh

418:

At its peak, Cholula had the second largest population in Mexico of an estimated 100,000 people living at this site. Though the ancient city of Cholula remained inhabited, residents abandoned the Great Pyramid in the 8th century as the city suffered a drastic population drop. Even after this

790:, bone needles, spindles, and pots. The male skeleton probably belonged to a renowned warrior. His grave goods are far richer, with ritual vessels, and elegant vase with a multicolored design, obsidian arrowheads, and a musical instrument called an omexicahuaztli. A jawbone of a

1014:(the god of rain) due to the drought occurring at this site. The disarticulated remains of at least 46 individuals were found in the area of an altar in the centre of a plaza at the southwest corner of the pyramid. These remains included individuals of all ages and both sexes.

355:

The Great Pyramid was an important religious and mythical centre in preinvasion times. Over a period of a thousand years prior to the Spanish Invasion, consecutive construction phases gradually built up the bulk of the pyramid until it became the largest in Mexico by volume.

897:

is a more traditional ritual monument for Mesoamerica and fits the altar genre. It is a narrow rectangular stone, oriented to the east, in a horizontal position. It functioned as a kind of pedestal, with each of the sides richly ornamented. On one side, there are two

652:

and others in the project worked on more multidisciplinary tasks, such as determining agricultural patterns of the site, ceramic development and water distribution systems. However, this put them in conflict with the sponsors of the project, along with the

624:. The pieces ranged from clay figures made when the settlement was just a village, to the Pre-classic. The latter ones include figures that are definitely nude females with complicated hair styles. Figures from later periods, such as those coinciding with

773:

type of altar, which are placed on ceremonial platforms. It has a square base with its north, south, and west sides done in talud that rise up to a decorated section that is topped with a cornice. The access stairs have parallel beams that culminate in

647:

in 1966. After only six months of work, Messmacher released a preliminary report in 1967. One of the main finds during this time was that of Edificio I (Building I). In addition to the excavating of the main structures of the pyramid, Messmacher,

578:

The pyramid was excavated in two phases. The first began in 1931 and ended in the 1950s. Excavations began again in 1966 and officially ended in 1970, with the publication of the reports of the various academics who worked on Proyecto Cholula.

1009:

The remains of eight individuals were found under the slab flooring of the Courtyard of Altars. These included the remains of a number of children that were deposited in ceramic pots. These children were thought to have been messengers to

732:

Initial excavations eventually indicated that the main access to the pyramid was on the west side, which latter excavations confirmed. Both also showed that there usually were minor accesses on the northeast and southwest corners.

602:

entrance, due to its deteriorated condition, but the archaeologists decided to begin tunnelling on the north side, where colonial construction had damaged it. On this side, the remains of walls and other structures could be seen.

729:. Around the pyramid are a number of other structures and patios, which form a massive complex. The Patio of the Altars was the main access to the pyramid and is named for the various altars that surround a main courtyard.

843:

The Courtyard of Altars is a complex of buildings adjoining the south side of the pyramid. It was one of the most important finds of the 1967 to 1970s round of excavation, named such because of several altars found here.

640:

and state governments, who wanted to make Cholula an attraction, as well. The archaeology and anthropology fields had experienced changes since Marquina's work, mostly focusing on a more interdisciplinary approach.

705:

687:

Of all the work done from the 1930s to the 1950s, there was only one presentation, at the XXVII Congreso Internacional de Americanistas de México in 1939. In 1951, Marquina included Cholula in a work called

502:

Because of the historic and religious significance of the church, which is a designated monument, the pyramid as a whole has not been excavated and restored, as have the smaller but better-known pyramids at

883:

sculpture, which has allowed for the recovery of some of the fragments of Cholula's history. The centre section of each altar was left blank but may originally have been painted with religious designs.

620:

During the first round of excavations, sixteen holes were dug in the area by Eduardo Noguera to extract ceramic materials and establish a time line. The results of these were published in 1954 as

863:. Some sections of this decoration still display original colouring, with diagonal bands of red, blue, yellow, black and turquoise. The decoration also includes symbols that may represent stars.

368:

Comparison of approximate profiles of the Great Pyramid of Cholula with some notable pyramidal or near-pyramidal buildings. Dotted lines indicate original heights, where data is available. In

1065:

407:, which is about 2.5 million cubic metres. The ceramics of Cholula were closely linked to those of Teotihuacan, and both sites appeared to decline simultaneously. The Postclassic

2464:

472:

467:

Architect Ignacio Marquina started exploratory tunnelling within the pyramid in 1931. By 1954, the total length of tunnels came to approximately 8.0 kilometres (5 mi).

891:

there are few decorative features, leading some to speculate that it was painted. New studies show similarities between this stone and decorative elements at El Tajín.

2289:

Solís Olguín, Felipe; Velázquez, Verónica (2007). "Capítulo III – Sabíos y archeólogos en pos de los restos de la antigua ciudad". In Solís Olguín, Felipe (ed.).

680:. There are a number of possible reasons for this. One is that its existence was not greatly elaborated in a publication by the Mexican government for the 1928

2500:

2063:

2515:

316:

municipality, and marks the area in the center of the city where this municipality begins. The city is divided into two municipalities called San Andrés and

628:

and Teotihuacan, tend to be of gods and priests. Various musical instruments, such as flutes, were also found, as well as tools for the making of textiles,

261:. It is the largest archaeological site of a pyramid (temple) in the world, as well as the largest pyramid by volume known to exist in the world today. The

2584:

85:

814:

The final phase covered Building C, burying it within its adobe core. The facing of this phase has collapsed to give the impression of a natural hill.

2594:

2495:

2426:

43:

1210:

684:

in New York. There is only one short mention of the pyramid in the entire work. However, by this time, only Bandelier had done any work on the site.

778:– an element found in Tenayuca and other Mexica areas. The name comes from the three human skulls made from clay, with bulging eyes and covered in

668:

Despite the site's pre-Hispanic importance, this pyramid is relatively unknown and unstudied, especially in comparison to others in Mexico such as

2589:

2474:

1035:

of central Mexico, the pyramid has not been extensively studied and has not of yet played a significant role in the understanding of Mesoamerica.

681:

725:

with a black skull in the middle. And the other is the "Bebedores," which depicts various figures drinking out of vessels most commonly used for

764:

One of the most important discoveries between 1932 and 1936 was the Altar of the Sculpted Skulls, which was officially reported by archeologist

2609:

1900:[San Pedro Cholula-Traditions and Legends] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from

154:

57:

2454:

2325:

2302:

2262:

1407:

1127:

2545:

488:

2505:

399:

ever constructed anywhere in the world, with a total volume estimated at over 4.45 million cubic metres, larger than that of the taller

2510:

2357:

2222:

2187:

2149:

568:

1956:[San Pedro Cholula – The City] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from

1284:

1117:

617:

tunnels, with two more added by 1951. The tunnels demonstrate the real value of the pyramid, which is not visible on the surface.

2449:

1003:

786:. It contains the remains of a man and woman. The female skeleton is accompanied by grave goods related to domestic life such as

459:

pyramid was overgrown, and by the 19th century it was still undisturbed, with only the church built in the 16th century visible.

782:, along with the rest of the structure. This ornamental feature relates to the function of the altar, which is believed to be a

879:

Four altars were excavated from the final construction phase of the Courtyard of Altars. Three of them were decorated with low

575:

two nearby mounds called the Cerro de Acozac and the Cerro de la Cruz, which at that time were totally covered in vegetation.

710:

2110:

1897:

2419:

313:

2089:

Rivas, Francisco (March 3, 2007). "Vigilan Cholula al estilo canadiense" [Watching over Cholula Canadian style].

1624:

Urban population dynamics in a preindustrial New World city: Morbidity, mortality, and immigration in postclassic Cholula

2490:

2349:

2048:

Ibarra, Mariel (July 13, 2002). "Cholula: Antigedad en todos los rincones" [Cholula:Antiquity in every corner].

1096:

806:

or the Pyramid of the Nine Stories, was built over Building B between 350 and 450 AD, and is bigger by volume than the

415:

or "hand-made mountain", which means they believed the structure was built by human hands instead of by sacred beings.

2629:

2624:

2614:

1953:

1060:

519:

384:. It has a base of 300 by 315 metres (984 by 1,033 ft) and a height of 25 m (82 ft). According to the

2249:

Rodríguez, Dionisio (2007). "Capítulo IV – La pintura mural prehisánica de Cholula". In Solís Olguín, Felipe (ed.).

909:

it was found, it was lying on a platform, which indicates something happened to the site, but it is not known what.

586:

who dug tunnels to explore the substructures. This was a time of political instability in Mexico, mostly due to the

2604:

2599:

2067:

2018:

899:

548:

277:

499:

are found under Catholic sites, due to the practice of the Catholic Church of destroying local religious sites.

430:

where a group of tolteca-chichimeca arrive and conquer the city after running from their previous capital city,

2619:

2412:

2167:

625:

431:

386:

1979:

Rivas, Francisco (April 10, 2007). "Impiden rescatar vestigios" [Preventing the recovery of remains].

598:

in the 1920s. The project was given to Marquina because of his experience working with Gamio in Teotihuacan.

845:

649:

529:

1218:

479:

2469:

590:. However, the decision was made to excavate the structure because of the success of the excavations of

538:

400:

269:

265:

644:

551:

that is characteristic of the region, and that became strongly associated with the great metropolis of

495:

destination, and the site is also used for the celebration of many native rites. Many ancient sites in

369:

583:

765:

116:

807:

775:

268:

stands 25 metres (82 ft) above the surrounding plain, which is significantly shorter than the

1217:(in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo. 2009. Archived from

364:

2214:

2141:

1326:

2531:

2392:

2384:

2363:

2353:

2321:

2298:

2277:

2258:

2228:

2218:

2193:

2183:

2155:

2145:

1403:

1123:

770:

317:

787:

285:

2003:

Ramírez, Clara (June 29, 2003). "Es Cholula zona viva" [Cholula is a living zone].

426:

meaning "the place of those who fled", a clear reference to the events written on the text

304:

The Cholula archaeological zone is situated 6.4 kilometres (4 mi) west of the city of

2435:

1399:

309:

250:

1150:

2240:

Ramírez, Clara (2003-06-29). "Es Cholula zona viva" [Cholula is a living zone].

613:" like those found in Mayan constructions, rather than adding beams and other supports.

2134:

2129:

941:

The subject of the mural is a feast, featuring personages drinking what is most likely

791:

677:

657:, which favored a more restricted approach that focused on reconstructing the pyramid.

556:

446:, a codex from the Cholula region, relates that an Olmec-Xicalanca lord with the title

305:

289:

1882:

Rivas, Francisco (March 15, 2007). "Protegen a Cholula" [Protecting Cholula].

1038:

2578:

2207:

2179:

2172:

856:

636:

carved from bone, with images related to the concept of life and death as a duality.

545:

496:

212:

1312:

605:

Tunnelling techniques relied on various team members' experience at Teotihuacan and

921:

835:

673:

595:

587:

381:

376:

The temple-pyramid complex was built in four stages, starting from the 3rd century

273:

1392:

2114:

2113:(in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. Archived from

1901:

824:

722:

714:

697:

it is not possible to reconstruct the last stage of the pyramid to what it was.

669:

610:

591:

552:

508:

504:

293:

281:

262:

17:

1022:

984:

871:

492:

455:

377:

2560:

2547:

2388:

2281:

1006:, as demonstrated by mangled body parts and skulls from decapitated victims.

507:. Inside the pyramid are some five miles (8 km) of tunnels excavated by

169:

156:

2396:

2367:

2294:

2254:

2232:

2197:

2159:

1327:"Anales de Cuauhtinchan. Historia Tolteca Chichimeca. Libro de la Conquista"

783:

746:

1957:

347:

1100:

606:

396:

2178:. Pelican Books series (1990 reprint ed.). Harmondsworth, England:

2026:

633:

392:

332:

246:

769:

are stairs to climb the platform. For this reason, it is considered a

419:

population drop, the Great Pyramid retained its religious importance.

1011:

942:

880:

779:

726:

451:

408:

258:

254:

142:

132:

120:

1626:(PhD thesis). The Pennsylvania State University. Docket AAT 3436082.

661:

keeping experts in areas such as geology, botany and paleozoology.

559:. The west was damaged later with the installation of a rail line.

2404:

1037:

983:

920:

834:

704:

629:

534:

518:

484:

470:

Today the pyramid at first looks like a natural hill. This is the

404:

363:

346:

945:. Several of the displayed figures are wearing cloth turbans and

541:. Tlachihualtepetl has the largest pyramid base in the Americas.

2022:

654:

582:

Exploration of the pyramid itself began in 1931 under architect

2408:

2320:] (in Spanish). Puebla, Mexico: Media IV Impresion Visual.

227:

Responsible body: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

523:

Artist's conception of what the pyramid might have looked like

483:(Sanctuary of the Virgin of Remedies), which was built by the

372:, hover over a pyramid to highlight and click for its article.

450:

resided at the Great Pyramid. In the 12th century, after the

925:

One of the murals of Building 3 covered by a protective roof

823:

painted with black square, vaguely resembling the niches of

2140:(5th, revised and enlarged ed.). London and New York:

380:

through the 9th century AD, and was dedicated to the deity

693:

such reconstruction is possible with the Cholula pyramid.

2276:. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

1151:"8 Largest Pyramids in the World (with Photos & Map)"

491:

times (1594) on top of the temple. The church is a major

239:

33:

27:

Archaeological complex located in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

1066:

List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

351:

Model of the various structures that make up the pyramid

2383:(13 (May–June 1995)). Mexico: Editorial Raíces: 24–30.

2066:. Let's Go Publications, Inc. 1960–2011. Archived from

1466:

Kastelein, Barbara (February 2004). "The Sacred City".

2346:

An Archaeological Guide to Central and Southern Mexico

913:

tradition, as similar figures were found in Tlaxcala.

2375:

Solanes Carraro, María del Carmen (1995). "Cholula".

632:

paper and axes. One major find included a ceremonial

249:

for "constructed mountain"), is a complex located in

1398:. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet Publications. pp.

1307:

1305:

1285:"Los túneles de la Gran Pirámide de Cholula, Puebla"

476:(Church of Our Lady of Remedies), also known as the

280:

style of the building was linked closely to that of

2524:

2483:

2442:

218:

208:

203:

198:

190:

185:

148:

138:

112:

2206:

2171:

2133:

1391:

1215:Municipal Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México

1116:Culture (15 August 2010). Kuiper, Kathleen (ed.).

1173:

1171:

1083:

1081:

567:The first study of the pyramid area was done by

92:

64:

2109:Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula (2008–2011).

1818:

1816:

1765:

1763:

1761:

1759:

1749:

1747:

1745:

1743:

1741:

1693:

1691:

1689:

1658:

1656:

1654:

1449:

1122:. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 42.

1119:Pre-Columbian America: Empires of the New World

1739:

1737:

1735:

1733:

1731:

1729:

1727:

1725:

1723:

1721:

1447:

1445:

1443:

1441:

1439:

1437:

1435:

1433:

1431:

1429:

1369:

1367:

1365:

1363:

1361:

1359:

1357:

1355:

1252:

1250:

1248:

1026:Image of the Virgin of the Remedies of Cholula

2420:

1238:

1236:

1196:

1194:

1192:

799:Building C or the Pyramid of the Nine Stories

8:

2111:"San Pedro Cholula – Tradiciones y Leyendas"

1898:"San Pedro Cholula – Tradiciones y Leyendas"

1670:

1668:

1635:

1633:

1461:

1459:

30:

2093:(in Spanish). Saltillo, Mexico. p. 12.

1998:

1996:

1994:

1992:

1990:

1921:

1919:

1877:

1875:

1873:

1617:

1615:

753:Building B or Pyramid of the Painted Skulls

643:The first person in charge of the site was

2501:Statue of Alfredo Toxqui Fernández de Lara

2427:

2413:

2405:

2272:Solanes Carraro, María del Carmen (1991).

1797:

1795:

1793:

1551:

1549:

1547:

1519:

1517:

1097:The giant pyramid hidden inside a mountain

29:

2465:Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios

544:The earliest construction phase features

473:Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios

100:Great Pyramid of Cholula (Puebla (state))

1385:

1383:

1381:

1379:

1111:

1109:

1021:

870:

1077:

682:Congreso Internacional de Americanistas

2244:(in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 11.

2052:(in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 16.

2007:(in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 11.

1983:(in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 10.

1886:(in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 11.

2136:Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs

528:Building of the pyramid began in the

7:

1177:Coe & Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 121.

1087:Coe & Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 120.

292:is evident as well, especially from

2516:Statue of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

622:La ceramica arqueológica de Cholula

2585:Buildings and structures in Puebla

2455:Church of Santa María Tonantzintla

709:Replica of the "Bebedores" mural,

25:

2318:Virgin of the Remedies in Cholula

2314:Virgen de los Remedios en Cholula

1622:Bullock Kreger, Meggan M (2010).

339:, which means "place of refuge".

2595:Archaeological museums in Mexico

2450:Church of San Francisco Acatepec

2312:Cordero Vazquez, Donato (2000).

312:. The pyramid is located in the

125:

91:

84:

63:

56:

42:

1954:"San Pedro Cholula – La Ciudad"

2590:Archaeological sites in Puebla

2475:San Gabriel Franciscan Convent

2174:The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico

1349:Solanes Carraro 1991, pp. 2–3.

1103:, retrieved on August 15, 2016

711:Museo Nacional de Antropologia

331:has its origin in the ancient

288:, although influence from the

1:

2610:Tourist attractions in Puebla

324:, meaning "artificial hill".

2496:San Miguel Arcángel Fountain

2491:Bust of Bernardino Rivadavia

2350:University of Oklahoma Press

902:extending along the length.

391:it is, in fact, the largest

72:Location within Mexico today

2019:"Estadística de Visitantes"

1753:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 6.

1453:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 5.

1373:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 7.

1256:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 4.

1242:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 3.

1211:"Puebla-San Andrés Cholula"

1200:Solanes Carraro 1991, p. 2.

855:is decorated with T-shaped

2646:

839:View of the main courtyard

314:San Andrés Cholula, Puebla

103:Show map of Puebla (state)

2511:Statue of Emiliano Zapata

2291:Cholula: la gran pirámide

2251:Cholula: la gran pirámide

1274:Davies 1982, 1990, p. 93.

1186:Davies 1982, 1990, p. 92.

1061:Cholula Mesoamerican site

1042:Facade of museum entrance

737:Building A or La Conejera

690:Arquitectura prehispánica

422:The site was once called

226:

50:

41:

2460:Great Pyramid of Cholula

1474:(2). Mexico City: 56–60.

1291:(in Spanish). 2016-08-16

444:Toltec-Chichimec History

438:Postclassic and Colonial

387:Guinness Book of Records

235:Great Pyramid of Cholula

31:Great Pyramid of Cholula

2506:Statue of Benito Juárez

2132:; Koontz, Rex (2002) .

1157:. Touropia. 9 June 2010

846:Eduardo Matos Moctezuma

650:Eduardo Matos Moctezuma

428:Anales de Cuauhtinchan,

395:as well as the largest

240:

34:

1331:pueblosoriginarios.com

1043:

1027:

989:

926:

876:

840:

717:

524:

480:Virgen de los Remedios

373:

370:its SVG file

352:

300:Location and etymology

194:Classic to Postclassic

2561:19.05750°N 98.30194°W

2470:Plaza de la Concordia

2344:Kelly, Joyce (2001).

2209:The Complete Pyramids

2205:Lehner, Mark (1997).

1904:on September 26, 2010

1849:Rodríguez, pp. 152–4.

1831:Rodríguez, pp. 136–7.

1041:

1025:

987:

924:

874:

838:

708:

539:Great Pyramid of Giza

522:

401:Great Pyramid of Giza

367:

350:

270:Great Pyramid of Giza

219:Architectural details

170:19.05750°N 98.30194°W

2377:Arqueología Mexicana

1810:Rodríguez, pp. 133–4

1394:Lonely Planet Mexico

1390:Noble, John (2008).

1289:Arqueología Mexicana

222:Number of temples: 1

209:Architectural styles

117:Cholula de Rivadabia

2566:19.05750; -98.30194

2557: /

2215:Thames & Hudson

2142:Thames & Hudson

831:Courtyard of Altars

808:Pyramid of the Moon

432:tollan-xicocotitlán

411:called the pyramid

175:19.05750; -98.30194

166: /

38:

2630:Mesoamerican sites

2625:Religion in Puebla

2615:Pyramids in Mexico

1960:on January 7, 2011

1840:Rodríguez, p. 138.

1822:Rodríguez, p. 137.

1697:Rodriguez, p. 135.

1662:Rodríguez, p. 134.

1044:

1028:

1018:Current importance

990:

927:

900:feathered serpents

877:

841:

718:

563:Excavation history

525:

374:

353:

75:Show map of Mexico

2605:History of Puebla

2600:Museums in Puebla

2540:

2539:

2532:San Pedro Cholula

2327:978-970-94806-6-5

2304:978-970-678-027-0

2264:978-970-678-027-0

1769:Rodríguez, p 136.

1648:Rodríguez p. 134.

1502:Solís, pp. 59–60.

1409:978-1-86450-089-9

1313:"Cholula Pyramid"

1129:978-1-61530-150-8

935:Mural of Drinkers

859:upon its sloping

645:Miguel Messmacher

530:Preclassic Period

308:, in the city of

231:

230:

16:(Redirected from

2637:

2572:

2571:

2569:

2568:

2567:

2562:

2558:

2555:

2554:

2553:

2550:

2429:

2422:

2415:

2406:

2400:

2371:

2331:

2308:

2285:

2268:

2245:

2236:

2212:

2201:

2177:

2163:

2139:

2125:

2123:

2122:

2095:

2094:

2086:

2080:

2079:

2077:

2075:

2070:on July 13, 2011

2060:

2054:

2053:

2045:

2039:

2038:

2036:

2034:

2025:. Archived from

2015:

2009:

2008:

2000:

1985:

1984:

1976:

1970:

1969:

1967:

1965:

1950:

1944:

1941:

1935:

1932:

1926:

1923:

1914:

1913:

1911:

1909:

1894:

1888:

1887:

1879:

1868:

1867:Solís, pp. 75–7.

1865:

1859:

1858:Solís, pp. 71–2.

1856:

1850:

1847:

1841:

1838:

1832:

1829:

1823:

1820:

1811:

1808:

1802:

1799:

1788:

1787:Solís, pp. 73–4.

1785:

1779:

1776:

1770:

1767:

1754:

1751:

1716:

1715:Solís, pp. 73–5.

1713:

1707:

1706:Solís, pp. 65–6.

1704:

1698:

1695:

1684:

1681:

1675:

1674:Solís, pp. 64–5.

1672:

1663:

1660:

1649:

1646:

1640:

1639:Solís, pp. 68–9.

1637:

1628:

1627:

1619:

1610:

1607:

1601:

1598:

1592:

1589:

1583:

1582:Solís, pp. 72–5.

1580:

1574:

1573:Solís, pp. 70–2.

1571:

1565:

1564:Solís, pp. 67–8.

1562:

1556:

1553:

1542:

1541:Solís, pp. 63–4.

1539:

1533:

1532:Solís, pp. 62–3.

1530:

1524:

1521:

1512:

1509:

1503:

1500:

1494:

1491:

1485:

1482:

1476:

1475:

1463:

1454:

1451:

1424:

1423:

1418:

1416:

1397:

1387:

1374:

1371:

1350:

1347:

1341:

1340:

1338:

1337:

1323:

1317:

1316:

1309:

1300:

1299:

1297:

1296:

1281:

1275:

1272:

1266:

1263:

1257:

1254:

1243:

1240:

1231:

1230:

1228:

1226:

1221:on July 22, 2011

1207:

1201:

1198:

1187:

1184:

1178:

1175:

1166:

1165:

1163:

1162:

1155:www.touropia.com

1147:

1141:

1140:

1138:

1136:

1113:

1104:

1094:

1088:

1085:

1004:human sacrifices

584:Ignacio Marquina

569:Adolph Bandelier

478:Santuario de la

448:Aquiyach Amapane

413:Tlachihualtépetl

322:Tlachihualtepetl

286:Valley of Mexico

243:

241:Tlachihualtepetl

237:, also known as

181:

180:

178:

177:

176:

171:

167:

164:

163:

162:

159:

131:

129:

128:

104:

95:

94:

88:

76:

67:

66:

60:

46:

39:

37:

35:Tlachihualtepetl

21:

18:Tlachihualtepetl

2645:

2644:

2640:

2639:

2638:

2636:

2635:

2634:

2620:Cholula, Puebla

2575:

2574:

2565:

2563:

2559:

2556:

2551:

2548:

2546:

2544:

2543:

2541:

2536:

2520:

2479:

2438:

2436:Cholula, Puebla

2433:

2403:

2374:

2360:

2343:

2339:

2337:Further reading

2334:

2328:

2311:

2305:

2288:

2274:Cholula, Puebla

2271:

2265:

2248:

2239:

2225:

2204:

2190:

2166:

2152:

2130:Coe, Michael D.

2128:

2120:

2118:

2108:

2104:

2099:

2098:

2088:

2087:

2083:

2073:

2071:

2062:

2061:

2057:

2047:

2046:

2042:

2032:

2030:

2017:

2016:

2012:

2002:

2001:

1988:

1978:

1977:

1973:

1963:

1961:

1952:

1951:

1947:

1942:

1938:

1933:

1929:

1924:

1917:

1907:

1905:

1896:

1895:

1891:

1881:

1880:

1871:

1866:

1862:

1857:

1853:

1848:

1844:

1839:

1835:

1830:

1826:

1821:

1814:

1809:

1805:

1800:

1791:

1786:

1782:

1777:

1773:

1768:

1757:

1752:

1719:

1714:

1710:

1705:

1701:

1696:

1687:

1683:Solís, pp. 6–7.

1682:

1678:

1673:

1666:

1661:

1652:

1647:

1643:

1638:

1631:

1621:

1620:

1613:

1608:

1604:

1599:

1595:

1590:

1586:

1581:

1577:

1572:

1568:

1563:

1559:

1554:

1545:

1540:

1536:

1531:

1527:

1522:

1515:

1510:

1506:

1501:

1497:

1492:

1488:

1483:

1479:

1468:Business Mexico

1465:

1464:

1457:

1452:

1427:

1414:

1412:

1410:

1389:

1388:

1377:

1372:

1353:

1348:

1344:

1335:

1333:

1325:

1324:

1320:

1311:

1310:

1303:

1294:

1292:

1283:

1282:

1278:

1273:

1269:

1264:

1260:

1255:

1246:

1241:

1234:

1224:

1222:

1209:

1208:

1204:

1199:

1190:

1185:

1181:

1176:

1169:

1160:

1158:

1149:

1148:

1144:

1134:

1132:

1130:

1115:

1114:

1107:

1095:

1091:

1086:

1079:

1074:

1057:

1020:

999:

982:

973:

964:

919:

869:

833:

820:

801:

766:Eduardo Noguera

755:

739:

703:

565:

517:

465:

440:

362:

345:

302:

174:

172:

168:

165:

160:

157:

155:

153:

152:

126:

124:

108:

107:

106:

105:

102:

101:

98:

97:

96:

79:

78:

77:

74:

73:

70:

69:

68:

32:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

2643:

2641:

2633:

2632:

2627:

2622:

2617:

2612:

2607:

2602:

2597:

2592:

2587:

2577:

2576:

2538:

2537:

2535:

2534:

2528:

2526:

2522:

2521:

2519:

2518:

2513:

2508:

2503:

2498:

2493:

2487:

2485:

2481:

2480:

2478:

2477:

2472:

2467:

2462:

2457:

2452:

2446:

2444:

2440:

2439:

2434:

2432:

2431:

2424:

2417:

2409:

2402:

2401:

2379:(in Spanish).

2372:

2358:

2340:

2338:

2335:

2333:

2332:

2326:

2309:

2303:

2286:

2269:

2263:

2246:

2237:

2223:

2202:

2188:

2164:

2150:

2126:

2105:

2103:

2100:

2097:

2096:

2081:

2055:

2040:

2029:on 8 July 2012

2021:(in Spanish).

2010:

1986:

1971:

1945:

1943:Vazquez, p. 18

1936:

1934:Vazquez, p. 15

1927:

1925:Vazquez, p. 14

1915:

1889:

1869:

1860:

1851:

1842:

1833:

1824:

1812:

1803:

1789:

1780:

1771:

1755:

1717:

1708:

1699:

1685:

1676:

1664:

1650:

1641:

1629:

1611:

1602:

1593:

1584:

1575:

1566:

1557:

1543:

1534:

1525:

1513:

1504:

1495:

1486:

1477:

1455:

1425:

1408:

1375:

1351:

1342:

1318:

1301:

1276:

1267:

1258:

1244:

1232:

1202:

1188:

1179:

1167:

1142:

1128:

1105:

1089:

1076:

1075:

1073:

1070:

1069:

1068:

1063:

1056:

1053:

1019:

1016:

998:

995:

981:

978:

972:

969:

963:

960:

918:

915:

868:

865:

832:

829:

819:

818:Other elements

816:

800:

797:

792:xoloitzcuintle

754:

751:

738:

735:

702:

699:

564:

561:

516:

513:

509:archaeologists

464:

463:Modern history

461:

439:

436:

361:

358:

344:

341:

301:

298:

229:

228:

224:

223:

220:

216:

215:

210:

206:

205:

201:

200:

196:

195:

192:

188:

187:

183:

182:

150:

146:

145:

140:

136:

135:

114:

110:

109:

99:

90:

89:

83:

82:

81:

80:

71:

62:

61:

55:

54:

53:

52:

51:

48:

47:

26:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

2642:

2631:

2628:

2626:

2623:

2621:

2618:

2616:

2613:

2611:

2608:

2606:

2603:

2601:

2598:

2596:

2593:

2591:

2588:

2586:

2583:

2582:

2580:

2573:

2570:

2533:

2530:

2529:

2527:

2523:

2517:

2514:

2512:

2509:

2507:

2504:

2502:

2499:

2497:

2494:

2492:

2489:

2488:

2486:

2482:

2476:

2473:

2471:

2468:

2466:

2463:

2461:

2458:

2456:

2453:

2451:

2448:

2447:

2445:

2441:

2437:

2430:

2425:

2423:

2418:

2416:

2411:

2410:

2407:

2398:

2394:

2390:

2386:

2382:

2378:

2373:

2369:

2365:

2361:

2359:0-8061-3349-X

2355:

2351:

2347:

2342:

2341:

2336:

2329:

2323:

2319:

2315:

2310:

2306:

2300:

2296:

2292:

2287:

2283:

2279:

2275:

2270:

2266:

2260:

2256:

2252:

2247:

2243:

2238:

2234:

2230:

2226:

2224:0-500-05084-8

2220:

2216:

2211:

2210:

2203:

2199:

2195:

2191:

2189:0-14-022232-4

2185:

2181:

2180:Penguin Books

2176:

2175:

2169:

2168:Davies, Nigel

2165:

2161:

2157:

2153:

2151:0-500-28346-X

2147:

2143:

2138:

2137:

2131:

2127:

2117:on 2010-09-26

2116:

2112:

2107:

2106:

2101:

2092:

2085:

2082:

2069:

2065:

2059:

2056:

2051:

2044:

2041:

2028:

2024:

2020:

2014:

2011:

2006:

1999:

1997:

1995:

1993:

1991:

1987:

1982:

1975:

1972:

1959:

1955:

1949:

1946:

1940:

1937:

1931:

1928:

1922:

1920:

1916:

1903:

1899:

1893:

1890:

1885:

1878:

1876:

1874:

1870:

1864:

1861:

1855:

1852:

1846:

1843:

1837:

1834:

1828:

1825:

1819:

1817:

1813:

1807:

1804:

1801:Solís, p. 74.

1798:

1796:

1794:

1790:

1784:

1781:

1778:Solís, p. 73.

1775:

1772:

1766:

1764:

1762:

1760:

1756:

1750:

1748:

1746:

1744:

1742:

1740:

1738:

1736:

1734:

1732:

1730:

1728:

1726:

1724:

1722:

1718:

1712:

1709:

1703:

1700:

1694:

1692:

1690:

1686:

1680:

1677:

1671:

1669:

1665:

1659:

1657:

1655:

1651:

1645:

1642:

1636:

1634:

1630:

1625:

1618:

1616:

1612:

1609:Solís, p. 70.

1606:

1603:

1600:Solís, p. 69.

1597:

1594:

1591:Solís, p. 77.

1588:

1585:

1579:

1576:

1570:

1567:

1561:

1558:

1555:Solís, p. 63.

1552:

1550:

1548:

1544:

1538:

1535:

1529:

1526:

1523:Solís, p. 62.

1520:

1518:

1514:

1511:Solís, p. 60.

1508:

1505:

1499:

1496:

1493:Solís, p. 61.

1490:

1487:

1484:Ramírez 2003.

1481:

1478:

1473:

1469:

1462:

1460:

1456:

1450:

1448:

1446:

1444:

1442:

1440:

1438:

1436:

1434:

1432:

1430:

1426:

1422:

1411:

1405:

1401:

1396:

1395:

1386:

1384:

1382:

1380:

1376:

1370:

1368:

1366:

1364:

1362:

1360:

1358:

1356:

1352:

1346:

1343:

1332:

1328:

1322:

1319:

1314:

1308:

1306:

1302:

1290:

1286:

1280:

1277:

1271:

1268:

1262:

1259:

1253:

1251:

1249:

1245:

1239:

1237:

1233:

1220:

1216:

1212:

1206:

1203:

1197:

1195:

1193:

1189:

1183:

1180:

1174:

1172:

1168:

1156:

1152:

1146:

1143:

1131:

1125:

1121:

1120:

1112:

1110:

1106:

1102:

1098:

1093:

1090:

1084:

1082:

1078:

1071:

1067:

1064:

1062:

1059:

1058:

1054:

1052:

1048:

1040:

1036:

1032:

1024:

1017:

1015:

1013:

1007:

1005:

996:

994:

986:

979:

977:

970:

968:

961:

959:

955:

951:

948:

944:

939:

936:

931:

923:

916:

914:

910:

907:

903:

901:

896:

892:

889:

885:

882:

873:

866:

864:

862:

858:

854:

850:

847:

837:

830:

828:

826:

817:

815:

812:

809:

805:

798:

796:

793:

789:

785:

781:

777:

772:

767:

762:

759:

752:

750:

748:

743:

736:

734:

730:

728:

724:

716:

712:

707:

700:

698:

694:

691:

685:

683:

679:

675:

671:

666:

662:

658:

656:

651:

646:

641:

637:

635:

631:

627:

623:

618:

614:

612:

608:

603:

599:

597:

593:

589:

585:

580:

576:

572:

570:

562:

560:

558:

554:

550:

547:

546:talud-tablero

542:

540:

536:

531:

521:

514:

512:

510:

506:

500:

498:

497:Latin America

494:

490:

486:

482:

481:

475:

474:

468:

462:

460:

457:

453:

449:

445:

437:

435:

433:

429:

425:

420:

416:

414:

410:

406:

402:

398:

394:

390:

388:

383:

379:

371:

366:

359:

357:

349:

342:

340:

338:

334:

330:

325:

323:

319:

315:

311:

307:

299:

297:

295:

291:

287:

283:

279:

278:architectural

275:

271:

267:

264:

260:

256:

252:

248:

244:

242:

236:

225:

221:

217:

214:

213:Talud-tablero

211:

207:

202:

197:

193:

189:

184:

179:

151:

147:

144:

141:

137:

134:

122:

118:

115:

111:

87:

59:

49:

45:

40:

36:

19:

2542:

2459:

2380:

2376:

2345:

2317:

2313:

2290:

2273:

2250:

2241:

2208:

2173:

2135:

2119:. Retrieved

2115:the original

2090:

2084:

2074:February 10,

2072:. Retrieved

2068:the original

2058:

2049:

2043:

2031:. Retrieved

2027:the original

2013:

2004:

1980:

1974:

1964:February 11,

1962:. Retrieved

1958:the original

1948:

1939:

1930:

1908:February 11,

1906:. Retrieved

1902:the original

1892:

1883:

1863:

1854:

1845:

1836:

1827:

1806:

1783:

1774:

1711:

1702:

1679:

1644:

1623:

1605:

1596:

1587:

1578:

1569:

1560:

1537:

1528:

1507:

1498:

1489:

1480:

1471:

1467:

1420:

1415:February 11,

1413:. Retrieved

1393:

1345:

1334:. Retrieved

1330:

1321:

1293:. Retrieved

1288:

1279:

1270:

1265:Lehner 1997.

1261:

1225:February 11,

1223:. Retrieved

1219:the original

1214:

1205:

1182:

1159:. Retrieved

1154:

1145:

1133:. Retrieved

1118:

1092:

1049:

1045:

1033:

1029:

1008:

1000:

991:

974:

965:

956:

952:

946:

940:

934:

932:

928:

911:

905:

904:

894:

893:

887:

886:

878:

860:

852:

851:

842:

821:

813:

803:

802:

763:

757:

756:

741:

740:

731:

723:grasshoppers

719:

695:

689:

686:

674:Chichen Itza

667:

663:

659:

642:

638:

621:

619:

615:

611:false arches

604:

600:

596:Manuel Gamio

588:Cristero War

581:

577:

573:

566:

549:architecture

543:

526:

501:

477:

471:

469:

466:

447:

443:

441:

427:

423:

421:

417:

412:

385:

382:Quetzalcoatl

375:

354:

336:

328:

326:

321:

303:

274:Quetzalcoatl

238:

234:

232:

204:Architecture

2564: /

853:Structure 4

715:Mexico City

678:Monte Albán

670:Teotihuacan

592:Teotihuacan

553:Teotihuacan

505:Teotihuacan

456:Chichimecas

282:Teotihuacan

263:adobe brick

173: /

149:Coordinates

2579:Categories

2552:98°18′07″W

2549:19°03′27″N

2484:Public art

2348:. Norman:

2293:. Mexico:

2253:. Mexico:

2213:. London:

2121:2011-02-11

2102:References

1336:2020-11-18

1295:2020-11-18

1161:2018-05-28

988:Building F

980:Building F

971:Building I

962:Building D

917:Mural work

804:Building C

758:Building B

742:Building A

493:pilgrimage

290:Gulf Coast

199:Site notes

161:98°18′07″W

158:19°03′27″N

2443:Landmarks

2389:0188-8218

2295:CONACULTA

2282:423698194

2255:CONACULTA