3021:, Rosier erroneously concludes that "as soon as I saw my own bead, a wave of pure probability flew, instantaneously, from one end of the room to the other. This accounted for the sudden change from two thirds to a half, as a finite quantum of probability (of weight one sixth) passed miraculously between the beads, launched by my own act of observation." Rosier explains his theory to Tissot, but "His poor grasp of my theories emerged some days later when, his sister being about to give birth, Tissot paid for a baby girl to be sent into the room, believing it would make the new child twice as likely to be born male. My pupil however gained a niece; and I found no difficulty in explaining the fallacy of his reasoning. Tissot had merely misunderstood my remarkable Paradox of the Twins, which states that if a boy tells you he has a sibling, then the probability of it being a sister is not a half, but two thirds." This is followed by a version of the

1878:

the car then B also does. For example, strategy A "pick door 1 then always stick with it" is dominated by the strategy B "pick door 2 then always switch after the host reveals a door": A wins when door 1 conceals the car, while B wins when either of the doors 1 or 3 conceals the car. Similarly, strategy A "pick door 1 then switch to door 2 (if offered), but do not switch to door 3 (if offered)" is dominated by strategy B "pick door 2 then always switch". A wins when door 1 conceals the car and Monty chooses to open door 2 or if door 3 conceals the car. Strategy B wins when either door 1 or door 3 conceals the car, that is, whenever A wins plus the case where door 1 conceals the car and Monty chooses to open door 3.

2959:". Adams initially answered, incorrectly, that the chances for the two remaining doors must each be one in two. After a reader wrote in to correct the mathematics of Adams's analysis, Adams agreed that mathematically he had been wrong. "You pick door #1. Now you're offered this choice: open door #1, or open door #2 and door #3. In the latter case you keep the prize if it's behind either door. You'd rather have a two-in-three shot at the prize than one-in-three, wouldn't you? If you think about it, the original problem offers you basically the same choice. Monty is saying in effect: you can keep your one door or you can have the other two doors, one of which (a non-prize door) I'll open for you." Adams did say the

2996:'." Hall clarified that as a game show host he did not have to follow the rules of the puzzle in the Savant column and did not always have to allow a person the opportunity to switch (e.g., he might open their door immediately if it was a losing door, might offer them money to not switch from a losing door to a winning door, or might allow them the opportunity to switch only if they had a winning door). "If the host is required to open a door all the time and offer you a switch, then you should take the switch," he said. "But if he has the choice whether to allow a switch or not, beware. Caveat emptor. It all depends on his mood."

1866:, and also some popular solutions correspond to this point of view. Savant asks for a decision, not a chance. And the chance aspects of how the car is hidden and how an unchosen door is opened are unknown. From this point of view, one has to remember that the player has two opportunities to make choices: first of all, which door to choose initially; and secondly, whether or not to switch. Since he does not know how the car is hidden nor how the host makes choices, he may be able to make use of his first choice opportunity, as it were to neutralize the actions of the team running the quiz show, including the host.

2732:. The three doors are replaced by a quantum system allowing three alternatives; opening a door and looking behind it is translated as making a particular measurement. The rules can be stated in this language, and once again the choice for the player is to stick with the initial choice, or change to another "orthogonal" option. The latter strategy turns out to double the chances, just as in the classical case. However, if the show host has not randomized the position of the prize in a fully quantum mechanical way, the player can do even better, and can sometimes even win the prize with certainty.

317:

744:

1,000,000, the remaining door will contain the prize. Intuitively, the player should ask how likely it is that, given a million doors, they managed to pick the right one initially. Stibel et al. proposed that working memory demand is taxed during the Monty Hall problem and that this forces people to "collapse" their choices into two equally probable options. They report that when the number of options is increased to more than 7 people tend to switch more often; however, most contestants still incorrectly judge the probability of success to be 50%.

1787:, the posterior odds on the location of the car, given that the host opens door 3, are equal to the prior odds multiplied by the Bayes factor or likelihood, which is, by definition, the probability of the new piece of information (host opens door 3) under each of the hypotheses considered (location of the car). Now, since the player initially chose door 1, the chance that the host opens door 3 is 50% if the car is behind door 1, 100% if the car is behind door 2, 0% if the car is behind door 3. Thus the Bayes factor consists of the ratios

1641:

1634:

1627:

1035:. As one source says, "the distinction between seems to confound many". The fact that these are different can be shown by varying the problem so that these two probabilities have different numeric values. For example, assume the contestant knows that Monty does not open the second door randomly among all legal alternatives but instead, when given an opportunity to choose between two losing doors, Monty will open the one on the right. In this situation, the following two questions have different answers:

1620:

187:

player: the host's action adds value to the door not eliminated, but not to the one chosen by the contestant originally. Another insight is that switching doors is a different action from choosing between the two remaining doors at random, as the former action uses the previous information and the latter does not. Other possible behaviors of the host than the one described can reveal different additional information, or none at all, and yield different probabilities.

1593:

1906:

2031:

because two options remained (or an equivalent error), the chances were even. Very few raised questions about ambiguity, and the letters actually published in the column were not among those few." The answer follows if the car is placed randomly behind any door, the host must open a door revealing a goat regardless of the player's initial choice and, if two doors are available, chooses which one to open randomly. The table below shows a variety of

688:

1579:

463:

2042:. For example, if the host is not required to make the offer to switch the player may suspect the host is malicious and makes the offers more often if the player has initially selected the car. In general, the answer to this sort of question depends on the specific assumptions made about the host's behavior, and might range from "ignore the host completely" to "toss a coin and switch if it comes up heads"; see the last row of the table below.

1586:

644:

3013:(2000) contains a version of the Monty Hall problem set in the 18th century. In Chapter 1 it is presented as a shell game that a prisoner must win in order to save his life. In Chapter 8 the philosopher Rosier, his student Tissot and Tissot's wife test the probabilities by simulation and verify the counter-intuitive result. They then perform an experiment involving black and white beads resembling the

1489:

22:

736:. I'll help you by using my knowledge of where the prize is to open one of those two doors to show you that it does not hide the prize. You can now take advantage of this additional information. Your choice of door A has a chance of 1 in 3 of being the winner. I have not changed that. But by eliminating door C, I have shown you that the probability that door B hides the prize is 2 in 3.

2988:

insistence that the probability was 1 out of 2. "That's the same assumption contestants would make on the show after I showed them there was nothing behind one door," he said. "They'd think the odds on their door had now gone up to 1 in 2, so they hated to give up the door no matter how much money I offered. By opening that door we were applying pressure. We called it the

2752:. In this puzzle, there are three boxes: a box containing two gold coins, a box with two silver coins, and a box with one of each. After choosing a box at random and withdrawing one coin at random that happens to be a gold coin, the question is what is the probability that the other coin is gold. As in the Monty Hall problem, the intuitive answer is

2838:. The warden obliges, (secretly) flipping a coin to decide which name to provide if the prisoner who is asking is the one being pardoned. The question is whether knowing the warden's answer changes the prisoner's chances of being pardoned. This problem is equivalent to the Monty Hall problem; the prisoner asking the question still has a

1279:. But, knowing that the host can open one of the two unchosen doors to show a goat does not mean that opening a specific door would not affect the probability that the car is behind the door chosen initially. The point is, though we know in advance that the host will open a door and reveal a goat, we do not know

308:. It is also typically presumed that the car is initially hidden randomly behind the doors and that, if the player initially chooses the car, then the host's choice of which goat-hiding door to open is random. Some authors, independently or inclusively, assume that the player's initial choice is random as well.

1953:. The confusion as to which formalization is authoritative has led to considerable acrimony, particularly because this variant makes proofs more involved without altering the optimality of the always-switch strategy for the player. In this variant, the player can have different probabilities of winning

2805:

in 1959 is equivalent to the Monty Hall problem. This problem involves three condemned prisoners, a random one of whom has been secretly chosen to be pardoned. One of the prisoners begs the warden to tell him the name of one of the others to be executed, arguing that this reveals no information about

2413:): car is first hidden uniformly at random and host later chooses uniform random door to open without revealing the car and different from player's door; player first chooses uniform random door and later always switches to other closed door. With his strategy, the player has a win-chance of at least

1896:

setting of Gill, discarding the non-switching strategies reduces the game to the following simple variant: the host (or the TV-team) decides on the door to hide the car, and the contestant chooses two doors (i.e., the two doors remaining after the player's first, nominal, choice). The contestant wins

1366:

If we assume that the host opens a door at random, when given a choice, then which door the host opens gives us no information at all as to whether or not the car is behind door 1. In the simple solutions, we have already observed that the probability that the car is behind door 1, the door initially

1292:

of the former that the latter is true. Solutions based on the assertion that the host's actions cannot affect the probability that the car is behind the initially chosen appear persuasive, but the assertion is simply untrue unless both of the host's two choices are equally likely, if he has a choice.

1232:

complained in their response to Savant that Savant still had not actually responded to their own main point. Later in their response to Hogbin and Nijdam, they did agree that it was natural to suppose that the host chooses a door to open completely at random when he does have a choice, and hence that

474:

Most people conclude that switching does not matter, because there would be a 50% chance of finding the car behind either of the two unopened doors. This would be true if the host selected a door to open at random, but this is not the case. The host-opened door depends on the player's initial choice,

2963:

version left critical constraints unstated, and without those constraints, the chances of winning by switching were not necessarily two out of three (e.g., it was not reasonable to assume the host always opens a door). Numerous readers, however, wrote in to claim that Adams had been "right the first

2943:

in

September 1990. Though Savant gave the correct answer that switching would win two-thirds of the time, she estimates the magazine received 10,000 letters including close to 1,000 signed by PhDs, many on letterheads of mathematics and science departments, declaring that her solution was wrong. Due

2397:

Four-stage two-player game-theoretic. The player is playing against the show organizers (TV station) which includes the host. First stage: organizers choose a door (choice kept secret from player). Second stage: player makes a preliminary choice of door. Third stage: host opens a door. Fourth stage:

1873:

of contestant involves two actions: the initial choice of a door and the decision to switch (or to stick) which may depend on both the door initially chosen and the door to which the host offers switching. For instance, one contestant's strategy is "choose door 1, then switch to door 2 when offered,

1283:

door he will open. If the host chooses uniformly at random between doors hiding a goat (as is the case in the standard interpretation), this probability indeed remains unchanged, but if the host can choose non-randomly between such doors, then the specific door that the host opens reveals additional

754:

You blew it, and you blew it big! Since you seem to have difficulty grasping the basic principle at work here, I'll explain. After the host reveals a goat, you now have a one-in-two chance of being correct. Whether you change your selection or not, the odds are the same. There is enough mathematical

1877:

Elementary comparison of contestant's strategies shows that, for every strategy A, there is another strategy B "pick a door then switch no matter what happens" that dominates it. No matter how the car is hidden and no matter which rule the host uses when he has a choice between two goats, if A wins

1829:

behind door 1, the chance that the host opens door 3 is also 50%, because, when the host has a choice, either choice is equally likely. Therefore, whether or not the car is behind door 1, the chance that the host opens door 3 is 50%. The information "host opens door 3" contributes a Bayes factor or

1411:

must be the average of: the probability that the car is behind door 1, given that the host picked door 2, and the probability of car behind door 1, given the host picked door 3: this is because these are the only two possibilities. But, these two probabilities are the same. Therefore, they are both

614:

chance of finding the car has not been changed by the opening of one of these doors because Monty, knowing the location of the car, is certain to reveal a goat. The player's choice after the host opens a door is no different than if the host offered the player the option to switch from the original

91:

Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door

1920:

The simulation can be repeated several times to simulate multiple rounds of the game. The player picks one of the three cards, then, looking at the remaining two cards the 'host' discards a goat card. If the card remaining in the host's hand is the car card, this is recorded as a switching win; if

866:

Although these issues are mathematically significant, even when controlling for these factors, nearly all people still think each of the two unopened doors has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter. This "equal probability" assumption is a deeply rooted intuition. People

2030:

probability she gave as her original answer. "Anything else is a different question." "Virtually all of my critics understood the intended scenario. I personally read nearly three thousand letters (out of the many additional thousands that arrived) and found nearly every one insisting simply that

1849:

door is opened by the host (door 2 or door 3?) reveals no information at all about whether or not the car is behind door 1, and this is precisely what is alleged to be intuitively obvious by supporters of simple solutions, or using the idioms of mathematical proofs, "obviously true, by symmetry".

893:

Experimental evidence confirms that these are plausible explanations that do not depend on probability intuition. Another possibility is that people's intuition simply does not deal with the textbook version of the problem, but with a real game show setting. There, the possibility exists that the

1881:

Dominance is a strong reason to seek for a solution among always-switching strategies, under fairly general assumptions on the environment in which the contestant is making decisions. In particular, if the car is hidden by means of some randomization device – like tossing symmetric or asymmetric

743:

Savant suggests that the solution will be more intuitive with 1,000,000 doors rather than 3. In this case, there are 999,999 doors with goats behind them and one door with a prize. After the player picks a door, the host opens 999,998 of the remaining doors. On average, in 999,999 times out of

186:

The given probabilities depend on specific assumptions about how the host and contestant choose their doors. An important insight is that, with these standard conditions, there is more information about doors 2 and 3 than was available at the beginning of the game when door 1 was chosen by the

2987:

differed from the rules of the puzzle. In the article, Hall pointed out that because he had control over the way the game progressed, playing on the psychology of the contestant, the theoretical solution did not apply to the show's actual gameplay. He said he was not surprised at the experts'

1882:

three-sided die – the dominance implies that a strategy maximizing the probability of winning the car will be among three always-switching strategies, namely it will be the strategy that initially picks the least likely door then switches no matter which door to switch is offered by the host.

3038:(2003) the narrator Christopher discusses the Monty Hall Problem, describing its history and solution. He concludes, "And this shows that intuition can sometimes get things wrong. And intuition is what people use in life to make decisions. But logic can help you work out the right answer."

1508:

of winning by switching given the contestant initially picks door 1 and the host opens door 3 is the probability for the event "car is behind door 2 and host opens door 3" divided by the probability for "host opens door 3". These probabilities can be determined referring to the conditional

812:, agreed? Then I simply lift up an empty shell from the remaining other two. As I can (and will) do this regardless of what you've chosen, we've learned nothing to allow us to revise the odds on the shell under your finger." She also proposed a similar simulation with three playing cards.

2013:

in 1990 did not specifically state that the host would always open another door, or always offer a choice to switch, or even never open the door revealing the car. However, Savant made it clear in her second follow-up column that the intended host's behavior could only be what led to the

150:

chance that the car is behind one of the doors not chosen. This probability does not change after the host reveals a goat behind one of the unchosen doors. When the host provides information about the two unchosen doors (revealing that one of them does not have the car behind it), the

1267:, whose contributions were published along with the original paper, criticized the authors for altering Savant's wording and misinterpreting her intention. One discussant (William Bell) considered it a matter of taste whether one explicitly mentions that (by the standard conditions)

765:

Savant wrote in her first column on the Monty Hall problem that the player should switch. She received thousands of letters from her readers – the vast majority of which, including many from readers with PhDs, disagreed with her answer. During 1990–1991, three more of her columns in

977:

Among these sources are several that explicitly criticize the popularly presented "simple" solutions, saying these solutions are "correct but ... shaky", or do not "address the problem posed", or are "incomplete", or are "unconvincing and misleading", or are (most bluntly) "false".

1263:, is asking the first or second question, and whether this difference is significant. Behrends concludes that "One must consider the matter with care to see that both analyses are correct", which is not to say that they are the same. Several critics of the paper by Morgan

2049:

and

Gillman both show a more general solution where the car is (uniformly) randomly placed but the host is not constrained to pick uniformly randomly if the player has initially selected the car, which is how they both interpret the statement of the problem in

819:

readers' not realizing they were supposed to assume that the host must always reveal a goat, almost all her numerous correspondents had correctly understood the problem assumptions, and were still initially convinced that Savant's answer ("switch") was wrong.

1480:, cannot be improved, and underlines what already may well have been intuitively obvious: the choice facing the player is that between the door initially chosen, and the other door left closed by the host, the specific numbers on these doors are irrelevant.

863:, do not match the rules of the actual game show and do not fully specify the host's behavior or that the car's location is randomly selected. However, Krauss and Wang argue that people make the standard assumptions even if they are not explicitly stated.

833:

When first presented with the Monty Hall problem, an overwhelming majority of people assume that each door has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter. Out of 228 subjects in one study, only 13% chose to switch. In his book

894:

show master plays deceitfully by opening other doors only if a door with the car was initially chosen. A show master playing deceitfully half of the times modifies the winning chances in case one is offered to switch to "equal probability".

1921:

the host is holding a goat card, the round is recorded as a staying win. As this experiment is repeated over several rounds, the observed win rate for each strategy is likely to approximate its theoretical win probability, in line with the

1932:

whether switching will win the round for the player. If this is not convincing, the simulation can be done with the entire deck. In this variant, the car card goes to the host 51 times out of 52, and stays with the host no matter how many

1274:

Among the simple solutions, the "combined doors solution" comes closest to a conditional solution, as we saw in the discussion of methods using the concept of odds and Bayes' theorem. It is based on the deeply rooted intuition that

1070:, as is shown correctly by the "simple" solutions. But the answer to the second question is now different: the conditional probability the car is behind door 1 or door 2 given the host has opened door 3 (the door on the right) is

587:. These are the only cases where the host opens door 3, so if the player has picked door 1 and the host opens door 3, the car is twice as likely to be behind door 2 as door 1. The key is that if the car is behind door 2 the host

1548:

The conditional probability table below shows how 300 cases, in all of which the player initially chooses door 1, would be split up, on average, according to the location of the car and the choice of door to open by the host.

289:

version do not explicitly define the protocol of the host. However, Marilyn vos Savant's solution printed alongside

Whitaker's question implies, and both Selvin and Savant explicitly define, the role of the host as follows:

2199:

and 1. This means even without constraining the host to pick randomly if the player initially selects the car, the player is never worse off switching. However neither source suggests the player knows what the value of

1293:

The assertion therefore needs to be justified; without justification being given, the solution is at best incomplete. It can be the case that the answer is correct but the reasoning used to justify it is defective.

1118:). For this variation, the two questions yield different answers. This is partially because the assumed condition of the second question (that the host opens door 3) would only occur in this variant with probability

422:

win the car by switching because the other goat can no longer be picked – the host had to reveal its location – whereas if the contestant initially picks the car (1 of 3 doors), the contestant

2489:): car is first hidden uniformly at random and host later never opens a door; player first chooses a door uniformly at random and later never switches. Player's strategy guarantees a win-chance of at least

870:

The problem continues to attract the attention of cognitive psychologists. The typical behavior of the majority, i.e., not switching, may be explained by phenomena known in the psychological literature as:

2360:

The host knows what lies behind the doors, and (before the player's choice) chooses at random which goat to reveal. He offers the option to switch only when the player's choice happens to differ from his.

198:, wrote to the magazine, most of them calling Savant wrong. Even when given explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still did not accept that switching is the best strategy.

1357:

respectively given the contestant initially picks door 1 and the host opens door 3. The solutions in this section consider just those cases in which the player picked door 1 and the host opened door 3.

2617:

1256:

s mathematically-involved solution would appeal only to statisticians, whereas the equivalence of the conditional and unconditional solutions in the case of symmetry was intuitively obvious.

2924:, presented Selvin's problem as an example of what Martin calls the probability trap of treating non-random information as if it were random, and relates this to concepts in the game of

856:

on it, and they are ready to berate in print those who propose the right answer". Pigeons repeatedly exposed to the problem show that they rapidly learn to always switch, unlike humans.

2058:

version to emphasize that point when they restated the problem. They consider a scenario where the host chooses between revealing two goats with a preference expressed as a probability

1249:, as the unconditional probability of winning by switching (i.e., averaged over all possible situations). This equality was already emphasized by Bell (1992), who suggested that Morgan

1027:, and hence that switching is the winning strategy, if the player has to choose in advance between "always switching", and "always staying". However, the probability of winning by

215:

type, because the solution is so counterintuitive it can seem absurd but is nevertheless demonstrably true. The Monty Hall problem is mathematically related closely to the earlier

1633:

1626:

889:

The errors of omission vs. errors of commission effect, in which, all other things being equal, people prefer to make errors by inaction (Stay) as opposed to action (Switch).

4223:

2644:

1917:. Three cards from an ordinary deck are used to represent the three doors; one 'special' card represents the door with the car and two other cards represent the goat doors.

5388:. Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche e Metodi Matematici – Università di Bari, Southern Europe Research in Economic Studies – S.E.R.I.E.S. Working Paper no. 0012.

1640:

1619:

3034:

974:) given that the contestant initially picks door 1 and the host opens door 3; various ways to derive and understand this result were given in the previous subsections.

495:

probability that the car is behind each door. If the car is behind door 1, the host can open either door 2 or door 3, so the probability that the car is behind door 1

852:

writes: "No other statistical puzzle comes so close to fooling all the people all the time even Nobel physicists systematically give the wrong answer, and that they

415:

A player who stays with the initial choice wins in only one out of three of these equally likely possibilities, while a player who switches wins in two out of three.

328:

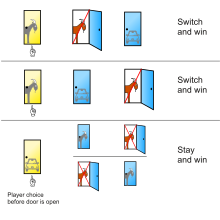

shows the three possible arrangements of one car and two goats behind three doors and the result of staying or switching after initially picking door 1 in each case:

796:

to illustrate: "You look away, and I put a pea under one of three shells. Then I ask you to put your finger on a shell. The odds that your choice contains a pea are

720:

says, "By opening his door, Monty is saying to the contestant 'There are two doors you did not choose, and the probability that the prize is behind one of them is

2673:

2883:

15 years later. The second appears to be the first use of the term "Monty Hall problem". The problem is actually an extrapolation from the game show. Monty Hall

2398:

player makes a final choice. The player wants to win the car, the TV station wants to keep it. This is a zero-sum two-person game. By von

Neumann's theorem from

1233:

the conditional probability of winning by switching (i.e., conditional given the situation the player is in when he has to make his choice) has the same value,

5275:

4650:

4642:

1001:...' is automatically fishy: probabilities are expressions of our ignorance about the world, and new information can change the extent of our ignorance."

5777:

5002:

3685:

1086:. This is because Monty's preference for rightmost doors means that he opens door 3 if the car is behind door 1 (which it is originally with probability

1913:

A simple way to demonstrate that a switching strategy really does win two out of three times with the standard assumptions is to simulate the game with

1768:

Many probability text books and articles in the field of probability theory derive the conditional probability solution through a formal application of

1818:. Given that the host opened door 3, the probability that the car is behind door 3 is zero, and it is twice as likely to be behind door 2 than door 1.

2948:

published an unprecedented four columns on the problem. As a result of the publicity the problem earned the alternative name "Marilyn and the Goats".

2336:"Mind-reading Monty": The host offers the option to switch in case the guest is determined to stay anyway or in case the guest will switch to a goat.

1428:. This shows that the chance that the car is behind door 1, given that the player initially chose this door and given that the host opened door 3, is

4883:

Gilovich, T.; Medvec, V.H. & Chen, S. (1995). "Commission, Omission, and

Dissonance Reduction: Coping with Regret in the "Monty Hall" Problem".

459: probability). The fact that the host subsequently reveals a goat in one of the unchosen doors changes nothing about the initial probability.

427:

win the car by switching. Using the switching strategy, winning or losing thus only depends on whether the contestant has initially chosen a goat (

5712:

2352:"Monty Fall" or "Ignorant Monty": The host does not know what lies behind the doors, and opens one at random that happens not to reveal the car.

2981:

himself was interviewed. Hall understood the problem, giving the reporter a demonstration with car keys and explaining how actual game play on

1825:

behind door 1, it is equally likely that it is behind door 2 or 3. Therefore, the chance that the host opens door 3 is 50%. Given that the car

1177:

claiming that Savant gave the correct advice but the wrong argument. They believed the question asked for the chance of the car behind door 2

7204:

6117:

5525:

5486:

4282:

2369:

The host opens a door and makes the offer to switch 100% of the time if the contestant initially picked the car, and 50% the time otherwise.

5757:

1949:

problem, does not make the simplifying assumption that the host must uniformly choose the door to open, but instead that he uses some other

1592:

1444:, and it follows that the chance that the car is behind door 2, given that the player initially chose door 1 and the host opened door 3, is

1288:(in the standard interpretation of the problem) the probability that the car is behind the initially chosen door does not change, but it is

7016:

5267:

1578:

320:

Three initial configurations of the game. In two of them, the player wins by switching away from the choice made before a door was opened.

2274:

The host always reveals a goat and always offers a switch. If and only if he has a choice, he chooses the leftmost goat with probability

4375:

D'Ariano, G. M.; Gill, R. D.; Keyl, M.; Kuemmerer, B.; Maassen, H.; Werner, R. F. (21 February 2002). "The

Quantum Monty Hall Problem".

2887:

open a wrong door to build excitement, but offered a known lesser prize – such as $ 100 cash – rather than a choice to switch doors. As

190:

Many readers of Savant's column refused to believe switching is beneficial and rejected her explanation. After the problem appeared in

7184:

6833:

6368:

6166:

5103:

4960:

4741:

5995:

4447:

1585:

96:

Savant's response was that the contestant should switch to the other door. By the standard assumptions, the switching strategy has a

6652:

6471:

5943:

5748:

5134:

4979:

4763:

4167:

4137:

1150:, it is never to the contestant's disadvantage to switch, as the conditional probability of winning by switching is always at least

476:

4806:

Gill, Richard (February 2011). "The Monty Hall

Problem is not a probability puzzle (it's a challenge in mathematical modelling)".

6273:

5423:

5221:

2038:

Determining the player's best strategy within a given set of other rules the host must follow is the type of problem studied in

6742:

5537:

4329:

4250:

3018:

1197:

and 1 depending on the host's decision process given the choice. Only when the decision is completely randomized is the chance

2560:

7194:

6283:

5086:

4918:

4709:

4200:

3055:

2724:

A quantum version of the paradox illustrates some points about the relation between classical or non-quantum information and

2679:

grows larger, the advantage decreases and approaches zero. At the other extreme, if the host opens all losing doors but one (

6612:

6061:

6020:

5879:

5854:

5829:

5810:

1317:, i.e., without taking account of which door was opened by the host. In accordance with this, most sources for the topic of

7189:

7199:

6793:

6211:

6186:

4854:

1011:

The simple solutions show in various ways that a contestant who is determined to switch will win the car with probability

770:

were devoted to the paradox. Numerous examples of letters from readers of Savant's columns are presented and discussed in

1181:

the player's initial choice of door 1 and the game host opening door 3, and they showed this chance was anything between

7143:

6569:

6323:

6313:

6248:

304:

When any of these assumptions is varied, it can change the probability of winning by switching doors as detailed in the

867:

strongly tend to think probability is evenly distributed across as many unknowns as are present, whether it is or not.

7179:

6363:

6343:

5341:

5056:

167:

chance of the car being behind one of the unchosen doors rests on the unchosen and unrevealed door, as opposed to the

6828:

5690:

5353:

Morgan, J. P.; Chaganty, N. R.; Dahiya, R. C. & Doviak, M. J. (1991). "Let's make a deal: The player's dilemma".

5268:"The Psychology of the Monty Hall Problem: Discovering Psychological Mechanisms for Solving a Tenacious Brain Teaser"

1779:

Initially, the car is equally likely to be behind any of the three doors: the odds on door 1, door 2, and door 3 are

4497:

Enßlin, Torsten A.; Westerkamp, Margret (April 2018). "The rationality of irrationality in the Monty Hall problem".

7077:

6798:

6456:

6298:

6293:

6068:

University of

California San Diego, Monty Knows Version and Monty Does Not Know Version, An Explanation of the Game

3022:

2557:

losing doors and then offers the player the opportunity to switch; in this variant switching wins with probability

2328:"Monty from Hell": The host offers the option to switch only when the player's initial choice is the winning door.

316:

2429:, however the TV station plays; with the TV station's strategy, the TV station will lose with probability at most

594:

Another way to understand the solution is to consider together the two doors initially unchosen by the player. As

7113:

7036:

6772:

6328:

6253:

6110:

5905:

5686:

5636:

5609:

5578:

5456:

5355:

5183:

4302:

3047:

2875:

2741:

1928:

Repeated plays also make it clearer why switching is the better strategy. After the player picks his card, it is

1322:

1301:

The simple solutions above show that a player with a strategy of switching wins the car with overall probability

907:

842:

300:

The host must always offer the chance to switch between the door chosen originally and the closed door remaining.

233:

220:

73:

4675:

7128:

6861:

6747:

6544:

6338:

6156:

2136:. These are the only cases where the host opens door 3, so the conditional probability of winning by switching

1993:. The variants are sometimes presented in succession in textbooks and articles intended to teach the basics of

1259:

There is disagreement in the literature regarding whether Savant's formulation of the problem, as presented in

847:

6931:

243:, dubbing it the "Monty Hall problem" in a subsequent letter. The problem is equivalent mathematically to the

2913:. Nalebuff, as later writers in mathematical economics, sees the problem as a simple and amusing exercise in

7133:

6732:

6702:

6358:

6146:

3076:

2788:

2098:

regardless of which door the host opens. If the player picks door 1 and the host's preference for door 3 is

1954:

1505:

244:

216:

7067:

5395:"The Monty Hall Dilemma Revisited: Understanding the Interaction of Problem Definition and Decision Making"

2531:

case: the host asks the player to open a door, then offers a switch in case the car has not been revealed.

1004:

Some say that these solutions answer a slightly different question – one phrasing is "you have to announce

7158:

7138:

7118:

6737:

6642:

6501:

6451:

6446:

6378:

6348:

6268:

6196:

6072:

5546:

1950:

693:

The host opens a door, the odds for the two sets don't change but the odds become 0 for the open door and

598:

puts it, "Monty is saying in effect: you can keep your one door or you can have the other two doors". The

418:

An intuitive explanation is that, if the contestant initially picks a goat (2 of 3 doors), the contestant

4187:

1874:

and do not switch to door 3 when offered". Twelve such deterministic strategies of the contestant exist.

879:, in which people tend to overvalue the winning probability of the door already chosen – already "owned".

6176:

5742:

4703:

3081:

2993:

1497:

981:

Sasha Volokh (2015) wrote that "any explanation that says something like 'the probability of door 1 was

6617:

6602:

5723:

5245:

2971:

column and its response received considerable attention in the press, including a front-page story in

547:. If the car is behind door 2 – with the player having picked door 1 – the host

6951:

6936:

6823:

6818:

6722:

6707:

6672:

6637:

6236:

6181:

6103:

5312:

4751:

4613:

4518:

4394:

2983:

1922:

1834:, on whether or not the car is behind door 1. Initially, the odds against door 1 hiding the car were

839:

239:

195:

59:

5551:

2622:

7108:

6727:

6677:

6514:

6441:

6421:

6278:

6161:

5782:

5677:

5669:

4719:

4691:

4551:

4228:, you pick door #1. Monty opens door #2 – no prize. Do you stay with door #1 or switch to #3?"

3071:

3014:

2895:

And if you ever get on my show, the rules hold fast for you – no trading boxes after the selection.

2801:

2729:

2725:

2344:"Angelic Monty": The host offers the option to switch only when the player has chosen incorrectly.

1974:

1885:

1821:

Richard Gill analyzes the likelihood for the host to open door 3 as follows. Given that the car is

253:

203:

7087:

6946:

6777:

6757:

6607:

6486:

6391:

6318:

6263:

5914:

5806:

5695:

5653:

5618:

5595:

5564:

5465:

5372:

5253:

5200:

5019:

4927:

4900:

4871:

4815:

4792:

4629:

4603:

4576:

4534:

4508:

4499:

4470:

4384:

4348:

4311:

2973:

2932:

1994:

1838:. Therefore, the posterior odds against door 1 hiding the car remain the same as the prior odds,

1492:

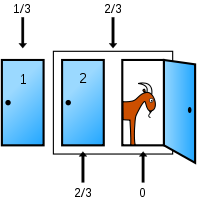

Tree showing the probability of every possible outcome if the player initially picks Door 1. The

78:

202:, one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, remained unconvinced until he was shown a

4430:

4410:

7072:

7041:

6996:

6891:

6762:

6717:

6692:

6622:

6496:

6426:

6416:

6308:

6258:

6206:

6025:

5978:

5939:

5815:

5787:

5521:

5482:

5161:

5112:

5099:

5080:

4988:

4975:

4956:

4759:

4737:

4667:

4594:

4568:

4278:

4232:

4196:

4163:

4133:

3693:

2956:

2728:, as encoded in the states of quantum mechanical systems. The formulation is loosely based on

1769:

1763:

782:

755:

illiteracy in this country, and we don't need the world's highest IQ propagating more. Shame!

83:

4272:

7153:

7148:

7082:

7046:

7026:

6986:

6956:

6911:

6866:

6851:

6808:

6662:

6303:

6240:

6226:

6191:

6089:

5935:

5645:

5587:

5556:

5432:

5364:

5321:

5284:

5230:

5192:

5151:

5143:

5011:

4937:

4892:

4863:

4825:

4772:

4659:

4621:

4560:

4526:

4462:

4338:

4259:

4248:

Barbeau, Edward (1993). "Fallacies, Flaws, and

Flimflam: The Problem of the Car and Goats".

2486:

2410:

2403:

2389:

1776:

form of Bayes' theorem, often called Bayes' rule, makes such a derivation more transparent.

876:

5954:

5903:

vos Savant, Marilyn (November 1991c). "Marilyn vos Savant's reply". Letters to the editor.

1905:

7051:

7011:

6966:

6881:

6876:

6597:

6549:

6436:

6201:

6171:

6141:

6003:

5394:

5212:

4849:

4784:

4643:"Partition-Edit-Count: Naive Extensional Reasoning in Judgment of Conditional Probability"

4478:

3059:

2925:

2879:

in 1975. The first letter presented the problem in a version close to its presentation in

2745:

2527:

2402:, if we allow both parties fully randomized strategies there exists a minimax solution or

2278:(which may depend on the player's initial choice) and the rightmost door with probability

1863:

1783:. This remains the case after the player has chosen door 1, by independence. According to

883:

462:

6916:

2652:

1858:

Going back to

Nalebuff, the Monty Hall problem is also much studied in the literature on

77:

in 1975. It became famous as a question from reader Craig F. Whitaker's letter quoted in

4617:

4522:

4398:

1220:

were supported by some writers, criticized by others; in each case a response by Morgan

687:

6991:

6981:

6971:

6906:

6896:

6886:

6871:

6667:

6647:

6632:

6627:

6587:

6554:

6539:

6534:

6524:

6333:

5414:

5156:

5125:

4838:

4686:

2792:

1946:

1031:

switching is a logically distinct concept from the probability of winning by switching

248:

5304:

2951:

In November 1990, an equally contentious discussion of Savant's article took place in

2300:

Vice versa, if the host opens the leftmost door, switching wins with probability 1/(1+

906:, including many introductory probability textbooks, solve the problem by showing the

7173:

7031:

7021:

6976:

6961:

6941:

6767:

6712:

6687:

6559:

6529:

6519:

6506:

6411:

6353:

6288:

6221:

6067:

5928:

5515:

5505:

5204:

5023:

4970:

Granberg, Donald (1996). "To Switch or Not to Switch". In vos Savant, Marilyn (ed.).

4904:

4829:

4730:

4633:

4564:

4474:

4352:

4153:

4123:

3004:

1893:

1784:

1510:

199:

5032:

4580:

4538:

2905:

A version of the problem very similar to the one that appeared three years later in

7006:

7001:

6856:

6431:

5670:"The Collapsing Choice Theory: Dissociating Choice and Judgment in Decision Making"

5591:

5576:

Selvin, Steve (February 1975a). "A problem in probability (letter to the editor)".

5568:

5497:

5385:

5368:

5117:

4993:

4777:

4589:

4426:

4406:

4343:

4324:

4263:

1914:

1493:

717:

269:

By the standard assumptions, the probability of winning the car after switching is

68:

50:

5607:

Selvin, Steve (August 1975b). "On the Monty Hall problem (letter to the editor)".

643:

6030:

5887:

5862:

5837:

5820:

5535:

Samuelson, W. & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). "Status quo bias in decision making".

2740:

The earliest of several probability puzzles related to the Monty Hall problem is

1957:

of the host, but in any case the probability of winning by switching is at least

7123:

6926:

6921:

6901:

6697:

6682:

6491:

6461:

6396:

6386:

6216:

6151:

6127:

6081:

5665:

5096:

Stochastik für Einsteiger: Eine Einführung in die faszinierende Welt des Zufalls

4663:

4362:

4219:

4183:

3029:

2989:

2952:

2914:

2399:

2039:

1998:

1889:

1859:

1318:

1271:

door is opened by the host is independent of whether one should want to switch.

903:

778:

595:

115:

of winning the car, while the strategy of keeping the initial choice has only a

112:

54:

4625:

4549:(1992). "A closer look at the probabilities of the notorious three prisoners".

4157:

4127:

2445:, however the player plays. The fact that these two strategies match (at least

1488:

6752:

6406:

5288:

5052:

4942:

4913:

2978:

2888:

2118:, while the probability the host opens door 3 and the car is behind door 1 is

1897:(and her opponent loses) if the car is behind one of the two doors she chose.

793:

64:

21:

5791:

5325:

5015:

4896:

3697:

2102:, then the probability the host opens door 3 and the car is behind door 2 is

1134:. However, as long as the initial probability the car is behind each door is

6657:

6577:

6401:

6000:

StatProb: The Encyclopedia Sponsored by Statistics and Probability Societies

5196:

4844:. Mathematical Institute, University of Leiden, Netherlands. pp. 10–13.

4546:

4466:

1945:

A common variant of the problem, assumed by several academic authors as the

591:

open door 3, but if the car is behind door 1 the host can open either door.

5165:

5064:

4671:

4530:

886:, in which people prefer to keep the choice of door they have made already.

4697:

The Second Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions

4572:

7092:

6592:

4608:

4389:

4325:"Pedigrees, Prizes, and Prisoners: The Misuse of Conditional Probability"

3668:

3666:

3664:

3662:

3660:

3658:

3656:

3654:

3652:

2001:. A considerable number of other generalizations have also been studied.

1277:

revealing information that is already known does not affect probabilities

294:

The host must always open a door that was not selected by the contestant.

6095:

5437:

5418:

5235:

5216:

5000:

Granberg, Donald & Brown, Thad A. (1995). "The Monty Hall Dilemma".

183:

chance of the car being behind the door the contestant chose initially.

6813:

6803:

6481:

5918:

5657:

5622:

5599:

5560:

5469:

5376:

4875:

4315:

2183:

can vary between 0 and 1 this conditional probability can vary between

285:. This solution is due to the behavior of the host. Ambiguities in the

211:

6064:– the original question and responses on Marilyn vos Savant's web site

5419:"Puzzles: Choose a Curtain, Duel-ity, Two Point Conversions, and More"

3627:

3625:

1216:

In an invited comment and in subsequent letters to the editor, Morgan

1033:

given that the player has picked door 1 and the host has opened door 3

6076:

5246:"Bias Trigger Manipulation and Task-Form Understanding in Monty Hall"

5217:"Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias"

5147:

3009:

2553:-door generalization of the original problem in which the host opens

5649:

4867:

4820:

4797:

3838:

3836:

3834:

2035:

possible host behaviors and the impact on the success of switching.

619:

remaining doors. The switch in this case clearly gives the player a

297:

The host must always open a door to reveal a goat and never the car.

4513:

1102:) or if the car is behind door 2 (also originally with probability

6582:

4932:

2873:

Steve Selvin posed the Monty Hall problem in a pair of letters to

2054:

despite the author's disclaimers. Both changed the wording of the

1904:

466:

A different selection process, where the player chooses at random

461:

315:

20:

5303:

Lucas, Stephen; Rosenhouse, Jason & Schepler, Andrew (2009).

3390:

3388:

1048:

given the player has picked door 1 and the host has opened door 3

257:

in 1959 and the Three Shells Problem described in Gardner's book

33:, to reveal a goat and offers to let the player switch from door

2482:

As previous, but now host has option not to open a door at all.

1773:

1751:

switching wins twice as often as staying (100 cases versus 50).

1746:

switching wins twice as often as staying (100 cases versus 50).

551:

open door 3, such the probability that the car is behind door 2

6099:

5098:(in German) (9th ed.). Springer. pp. 50–51, 105–107.

3576:

3574:

2240:

The host acts as noted in the specific version of the problem.

2204:

is so the player cannot attribute a probability other than the

67:. The problem was originally posed (and solved) in a letter by

2806:

his own fate but increases his chances of being pardoned from

1284:

information. The host can always open a door revealing a goat

4062:

2062:, having a value between 0 and 1. If the host picks randomly

785:" newspaper column) and reported in major newspapers such as

57:

puzzle, based nominally on the American television game show

5031:

Grinstead, Charles M. & Snell, J. Laurie (4 July 2006).

3429:

3427:

3257:

3255:

3253:

3251:

3249:

3247:

2505:. TV station's strategy guarantees a lose-chance of at most

1814:. Thus, the posterior odds become equal to the Bayes factor

1228:. In particular, Savant defended herself vigorously. Morgan

194:, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with

5130:) perform optimally on a version of the Monty Hall Dilemma"

4953:

The Monty Hall Dilemma: A Cognitive Illusion Par Excellence

3782:

3780:

1460:. The analysis also shows that the overall success rate of

1297:

Solutions using conditional probability and other solutions

815:

Savant commented that, though some confusion was caused by

772:

The Monty Hall Dilemma: A Cognitive Illusion Par Excellence

3740:

3738:

3672:

3272:

3270:

6082:"Stick or switch? Probability and the Monty Hall problem"

3797:

3795:

3595:

3593:

3591:

3589:

3192:

3190:

3188:

3152:

3150:

3148:

3146:

3144:

3142:

3140:

2854:

chance of being pardoned but his unnamed colleague has a

1513:. The conditional probability of winning by switching is

470:

any door has been opened, yields a different probability.

5976:

Whitaker, Craig F. (9 September 1990). ". Ask Marilyn".

4717:

Gardner, Martin (November 1959b). "Mathematical Games".

2920:"The Monty Hall Trap", Phillip Martin's 1989 article in

2691:

grows large (the probability of winning by switching is

2675:), the player is better off switching in every case. As

2612:{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{N}}\cdot {\frac {N-1}{N-p-1}}}

2549:

D. L. Ferguson (1975 in a letter to Selvin) suggests an

1046:

What is the probability of winning the car by switching

479:

does not hold. Before the host opens a door, there is a

6046:

vos Savant, Marilyn (26 November 2006). "Ask Marilyn".

5691:"Behind Monty Hall's Doors: Puzzle, Debate and Answer?"

5517:

Struck by Lightning: the Curious World of Probabilities

3962:

3960:

3958:

3916:

3914:

3631:

29:. The game host then opens one of the other doors, say

25:

In search of a new car, the player chooses a door, say

5244:

Kaivanto, K.; Kroll, E. B. & Zabinski, M. (2014).

3612:

3610:

3608:

3315:

3313:

3311:

3309:

3219:

3217:

777:

The discussion was replayed in other venues (e.g., in

92:

No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

5778:"An 'easy' answer to the infamous Monty Hall problem"

4592:(2002). "Quantum version of the Monty Hall problem".

3686:"An "easy" answer to the infamous Monty Hall problem"

3553:

3517:

3351:

3349:

3234:

3232:

3175:

3173:

3171:

3169:

3167:

3165:

3127:

3125:

3123:

3121:

3119:

3117:

3104:

3102:

3100:

3098:

3096:

2655:

2625:

2563:

1173:, four university professors published an article in

237:

in 1975, describing a problem based on the game show

134:

When the player first makes their choice, there is a

5393:

Mueser, Peter R. & Granberg, Donald (May 1999).

5173:

Hogbin, M.; Nijdam, W. (2010). "Letter to editor on

3336:

3334:

3332:

3330:

3328:

2964:

time" and that the correct chances were one in two.

1551:

792:

In an attempt to clarify her answer, she proposed a

7101:

7060:

6842:

6786:

6568:

6470:

6377:

6235:

6134:

5401:. University Library of Munich. Working Paper 99–06

3933:

3931:

3929:

3853:

3851:

3767:

3765:

3529:

3457:

2931:A restated version of Selvin's problem appeared in

2009:The version of the Monty Hall problem published in

1909:

Simulation of 29 outcomes of the Monty Hall problem

859:Most statements of the problem, notably the one in

5927:

4789:International Encyclopaedia of Statistical Science

4729:

3541:

3394:

3066:Similar puzzles in probability and decision theory

2667:

2646:, therefore switching always brings an advantage.

2638:

2611:

2245:(Specific case of the generalized form below with

902:As already remarked, most sources in the topic of

681:chance of being behind one of the other two doors.

5711:Vazsonyi, Andrew (December 1998 – January 1999).

5126:"Are birds smarter than mathematicians? Pigeons (

5034:Grinstead and Snell's Introduction to Probability

4189:The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

3035:The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

1772:; among them books by Gill and Henze. Use of the

5962:Course notes for Sociology Graduate Statistics I

3580:

3051:Episode 177 "Wheel of Mythfortune" – Pick a Door

2909:was published in 1987 in the Puzzles section of

2293:/3 ) door, switching wins with probability 1/(1+

1383:. Moreover, the host is certainly going to open

1224:is published alongside the letter or comment in

2893:

2227:Possible host behaviors in unspecified problem

1572:Player initially picks Door 1, 300 repetitions

1325:that the car is behind door 1 and door 2 to be

752:

665:chance of being behind the player's pick and a

89:

5758:"The 'Monty Hall' Problem: Everybody Is Wrong"

5124:Herbranson, W. T. & Schroeder, J. (2010).

3842:

3261:

3058:– similar application of Bayesian updating in

2477:) proves that they form the minimax solution.

2306:Always switching is the sum of these: ( 1/3 +

2243:Switching wins the car two-thirds of the time.

1749:On those occasions when the host opens Door 3,

1744:On those occasions when the host opens Door 2,

1039:What is the probability of winning the car by

6111:

5215:; Knetsch, J. L. & Thaler, R. H. (1991).

5075:. Includes 12 May 1975 letter to Steve Selvin

4050:

4014:

3433:

1509:probability table below, or to an equivalent

1484:Conditional probability by direct calculation

910:that the car is behind door 1 and door 2 are

8:

5446:Rao, M. Bhaskara (August 1992). "Comment on

4732:Aha! Gotcha: Paradoxes to Puzzle and Delight

4641:Fox, Craig R. & Levav, Jonathan (2004).

4360:Chun, Young H. (1991). "Game Show Problem".

3786:

6088:, 11 September 2013 (video). Mathematician

5276:Journal of Experimental Psychology: General

4651:Journal of Experimental Psychology: General

3744:

3565:

3288:

3196:

3156:

2687: − 2) the advantage increases as

2649:Even if the host opens only a single door (

1743:

1624:

1395:door is unspecified) does not change this.

6118:

6104:

6096:

5003:Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

4110:

3990:

3978:

3893:

3801:

3643:

3599:

3481:

3469:

3445:

3406:

3276:

2619:. This probability is always greater than

2289:If the host opens the rightmost ( P=1/3 +

5878:vos Savant, Marilyn (17 February 1991a).

5828:vos Savant, Marilyn (9 September 1990a).

5550:

5496:Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. (September 2005a).

5436:

5266:Krauss, Stefan & Wang, X. T. (2003).

5234:

5155:

4941:

4931:

4885:Personality and Social Psychology Journal

4819:

4796:

4607:

4512:

4433:. The Mathematical Association of America

4413:. The Mathematical Association of America

4388:

4342:

4292:Bell, William (August 1992). "Comment on

2654:

2626:

2624:

2577:

2564:

2562:

2534:Switching wins the car half of the time.

2364:Switching wins the car half of the time.

2355:Switching wins the car half of the time.

1977:of winning by switching is still exactly

305:

206:demonstrating Savant's predicted result.

5955:"Appendix D: The Monty Hall Controversy"

5853:vos Savant, Marilyn (2 December 1990b).

4038:

4002:

3966:

3920:

3813:

3505:

3418:

3379:

3223:

3208:

2223:

1487:

346:Result if switching to the door offered

330:

5756:VerBruggen, Robert (24 February 2015).

5668:; Dror, Itiel; Ben-Zeev, Talia (2008).

4689:(October 1959a). "Mathematical Games".

4074:

3729:

3717:

3616:

3319:

3300:

3238:

3179:

3131:

3108:

3092:

5740:

5386:"Monty Hall's Three Doors for Dummies"

5305:"The Monty Hall Problem, Reconsidered"

5078:

4701:

4431:"Devlin's Angle: Monty Hall revisited"

4162:. New York: Picador USA. p. 182.

4132:. New York: Picador USA. p. 178.

4098:

3949:

3367:

3355:

5498:"Monty Hall, Monty Fall, Monty Crawl"

3905:

3881:

3632:Lucas, Rosenhouse & Schepler 2009

3340:

1973:(and can be as high as 1), while the

1559:

7:

6019:vos Savant, Marilyn (7 July 1991b).

4086:

4026:

3937:

3869:

3857:

3825:

3771:

3493:

3017:, and in a humorous allusion to the

2911:The Journal of Economic Perspectives

2082:and switching wins with probability

1054:The answer to the first question is

324:The solution presented by Savant in

5630:Seymann, R. G. (1991). "Comment on

5384:Morone, A. & Fiore, A. (2007).

3756:

3554:Kaivanto, Kroll & Zabinski 2014

3518:Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler 1991

1567:(on average, 100 cases out of 300)

1562:(on average, 100 cases out of 300)

1557:(on average, 100 cases out of 300)

1367:chosen by the player, is initially

231:Steve Selvin wrote a letter to the

63:and named after its original host,

6167:First-player and second-player win

2768:, but the probability is actually

2220:that Savant assumed was implicit.

1613:Host must open Door 3 (100 cases)

1600:Host must open Door 2 (100 cases)

760:Scott Smith, University of Florida

251:'s "Mathematical Games" column in

14:

5135:Journal of Comparative Psychology

4852:(1992). "The Car and the Goats".

898:Criticism of the simple solutions

635:probability of choosing the car.

6274:Coalition-proof Nash equilibrium

6092:explains the Monty Hall paradox.

5996:"Monty Hall Problem (version 5)"

5424:Journal of Economic Perspectives

5222:Journal of Economic Perspectives

4837:Gill, Richard (17 March 2011a).

4830:10.1111/j.1467-9574.2010.00474.x

3542:Gilovich, Medvec & Chen 1995

3395:Stibel, Dror & Ben-Zeev 2008

2339:Switching always yields a goat.

2331:Switching always yields a goat.

1955:depending on the observed choice

1888:links the Monty Hall problem to

1639:

1632:

1625:

1618:

1591:

1584:

1577:

686:

642:

209:The problem is a paradox of the

5538:Journal of Risk and Uncertainty

5514:Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. (2005b).

4330:Journal of Statistics Education

4251:The College Mathematics Journal

3530:Samuelson & Zeckhauser 1988

3458:Herbranson & Schroeder 2010

3019:Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox

2347:Switching always wins the car.

1732:

1729:

1667:

1647:

1617:

1602:

1599:

1496:consists of exactly 4 possible

443: probability) or the car (

6284:Evolutionarily stable strategy

5934:. St. Martin's Press. p.

5776:Volokh, Sasha (2 March 2015).

5713:"Which Door Has the Cadillac?"

5592:10.1080/00031305.1975.10479121

5369:10.1080/00031305.1991.10475821

4919:The Mathematical Intelligencer

4791:. Springer. pp. 858–863.

4787:(2010). "Monty Hall problem".

4446:Eisenhauer, Joseph G. (2001).

4344:10.1080/10691898.2005.11910554

4264:10.1080/07468342.1993.11973519

3056:Principle of restricted choice

2944:to the overwhelming response,

2939:question-and-answer column of

2639:{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{N}}}

1:

6212:Simultaneous action selection

5930:The Power of Logical Thinking

5747:: CS1 maint: date and year (

4972:The Power of Logical Thinking

4855:American Mathematical Monthly

4277:. AMS Bookstore. p. 57.

1387:(different) door, so opening

1008:whether you plan to switch".

1006:before a door has been opened

997:, and nothing can change that

836:The Power of Logical Thinking

7205:Probability theory paradoxes

7144:List of games in game theory

6324:Quantal response equilibrium

6314:Perfect Bayesian equilibrium

6249:Bayes correlated equilibrium

5926:vos Savant, Marilyn (1996).

4758:. CRC Press. pp. 8–10.

4565:10.1016/0010-0277(92)90012-7

4411:"Devlin's Angle: Monty Hall"

3581:Enßlin & Westerkamp 2018

1854:Strategic dominance solution

1810:, while the prior odds were

1362:Refining the simple solution

343:Result if staying at door #1

6613:Optional prisoner's dilemma

6344:Self-confirming equilibrium

5481:. Oxford University Press.

4664:10.1037/0096-3445.133.4.626

2282: = 1 −

2138:given the host opens door 3

843:Massimo Piattelli Palmarini

81:'s "Ask Marilyn" column in

7223:

7078:Principal variation search

6794:Aumann's agreement theorem

6457:Strategy-stealing argument

6369:Trembling hand equilibrium

6299:Markov perfect equilibrium

6294:Mertens-stable equilibrium

5953:Williams, Richard (2004).

5477:Rosenhouse, Jason (2009).

5085:: CS1 maint: postscript (

4708:: CS1 maint: postscript (

4626:10.1103/PhysRevA.65.062318

4271:Behrends, Ehrhard (2008).

3843:Grinstead & Snell 2006

3720:, emphasis in the original

3262:Mueser & Granberg 1999

3023:unexpected hanging paradox

1937:-car cards are discarded.

1845:In words, the information

1761:

1608:Host randomly opens Door 3

1603:Host randomly opens Door 2

748:Savant and the media furor

615:chosen door to the set of

7185:Decision-making paradoxes

7114:Combinatorial game theory

6773:Princess and monster game

6329:Quasi-perfect equilibrium

6254:Bayesian Nash equilibrium

5906:The American Statistician

5637:The American Statistician

5634:: The player's dilemma".

5610:The American Statistician

5579:The American Statistician

5457:The American Statistician

5356:The American Statistician

5340:Martin, Phillip (1993) .

5289:10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.3

5184:The American Statistician

4951:Granberg, Donald (2014).

4943:10.1007/s00283-011-9253-0

4588:Flitney, Adrian P. &

4323:Carlton, Matthew (2005).

4303:The American Statistician

4195:. London: Jonathan Cape.

4051:Flitney & Abbott 2002

4015:Granberg & Brown 1995

3434:Granberg & Brown 1995

2876:The American Statistician

2226:

1748:

1631:

1583:

1571:

1564:

1554:

1323:conditional probabilities

1226:The American Statistician

1175:The American Statistician

908:conditional probabilities

555:the host opens door 3 is

499:the host opens door 3 is

7129:Evolutionary game theory

6862:Antoine Augustin Cournot

6748:Guess 2/3 of the average

6545:Strictly determined game

6339:Satisfaction equilibrium

6157:Escalation of commitment

5326:10.4169/002557009X478355

5094:Henze, Norbert (2011) .

5057:"The Monty Hall Problem"

5016:10.1177/0146167295217006

4897:10.1177/0146167295212008

4839:"The Monty Hall Problem"

4728:Gardner, Martin (1982).

4695:: 180–182. Reprinted in

4636:. Art. No. 062318, 2002.

3787:Hogbin & Nijdam 2010

2712:, which approaches 1 as

1565:Car hidden behind Door 2

1560:Car hidden behind Door 1

1555:Car hidden behind Door 3

7134:Glossary of game theory

6733:Stackelberg competition

6359:Strong Nash equilibrium

5994:Gill, Richard (2011b).

5722:: 17–19. Archived from

5197:10.1198/tast.2010.09227

4989:restricted online copy

4914:"The Mondee Gills Game"

4773:restricted online copy

4467:10.1111/1467-9639.00005

4448:"The Monty Hall Matrix"

4274:Five-Minute Mathematics

3566:Morone & Fiore 2007

3077:Sleeping Beauty problem

2789:Three Prisoners problem

2750:Calcul des probabilités

1901:Solutions by simulation

1610:(on average, 50 cases)

1605:(on average, 50 cases)

1506:conditional probability

824:Confusion and criticism

245:Three Prisoners problem

217:three prisoners problem

7159:Tragedy of the commons

7139:List of game theorists

7119:Confrontation analysis

6829:Sprague–Grundy theorem

6349:Sequential equilibrium

6269:Correlated equilibrium

5479:The Monty Hall Problem

5113:restricted online copy

4974:. St. Martin's Press.

4912:Gnedin, Sasha (2011).

4808:Statistica Neerlandica

4531:10.1002/andp.201800128

3482:Krauss & Wang 2003

3277:Krauss & Wang 2003

2903:

2742:Bertrand's box paradox

2669:

2640:

2613:

2322:) = 1/3 + 1/3 = 2/3 .

1910:

1757:

1501:

840:cognitive psychologist

757:

471:

321:

221:Bertrand's box paradox

219:and to the much older

94:

42:

7195:Mathematical problems

6932:Jean-François Mertens

6062:The Game Show Problem

5342:"The Monty Hall Trap"

4955:. Lumad/CreateSpace.

3082:Two envelopes problem

2994:The Turn of the Screw

2670:

2641:

2614:

1908:

1491:

475:so the assumption of

465:

319:

234:American Statistician

74:American Statistician

24:

7200:Probability problems

7061:Search optimizations

6937:Jennifer Tour Chayes

6824:Revelation principle

6819:Purification theorem

6758:Nash bargaining game

6723:Bertrand competition

6708:El Farol Bar problem

6673:Electronic mail game

6638:Lewis signaling game

6182:Hierarchy of beliefs

6029:: 26. Archived from

5886:: 12. Archived from

5861:: 25. Archived from

5836:: 16. Archived from

5348:. Granovetter Books.

5313:Mathematics Magazine

4409:(July–August 2003).

4063:D'Ariano et al. 2002

3828:, pp. 207, 213.

3506:Fox & Levav 2004

2653:

2623:

2561:

2160:which simplifies to

2005:Other host behaviors

1923:law of large numbers

1830:likelihood ratio of

829:Sources of confusion

709:for the closed door.

265:Standard assumptions

7109:Bounded rationality

6728:Cournot competition

6678:Rock paper scissors

6653:Battle of the sexes

6643:Volunteer's dilemma

6515:Perfect information

6442:Dominant strategies

6279:Epsilon-equilibrium

6162:Extensive-form game

5811:"Game Show Problem"

5807:vos Savant, Marilyn

5783:The Washington Post

5678:Theory and Decision

5438:10.1257/jep.1.2.157

5236:10.1257/jep.5.1.193

4720:Scientific American

4692:Scientific American

4618:2002PhRvA..65f2318F

4523:2019AnP...53100128E

4455:Teaching Statistics

4399:2002quant.ph..2120D

4222:(2 November 1990).

3845:, pp. 137–138.

3690:The Washington Post

3072:Boy or Girl paradox

3015:boy or girl paradox

2992:treatment. It was '

2802:Scientific American

2730:quantum game theory

2726:quantum information

2716:grows very large).

2668:{\displaystyle p=1}

1975:overall probability

1886:Strategic dominance

1816:1 : 2 : 0

1812:1 : 1 : 1

1808:1 : 2 : 0

1781:1 : 1 : 1

1504:By definition, the

254:Scientific American

204:computer simulation

53:, in the form of a

7180:1975 introductions

7088:Paranoid algorithm

7068:Alpha–beta pruning

6947:John Maynard Smith

6778:Rendezvous problem

6618:Traveler's dilemma

6608:Gift-exchange game

6603:Prisoner's dilemma

6520:Large Poisson game

6487:Bargaining problem

6392:Backward induction

6364:Subgame perfection

6319:Proper equilibrium

6033:on 21 January 2013

6006:on 21 January 2016

5890:on 21 January 2013

5865:on 21 January 2013

5840:on 21 January 2013

5696:The New York Times

5561:10.1007/bf00055564

5520:. Harper Collins.

5254:Economics Bulletin

4500:Annalen der Physik

4377:Quant. Inf. Comput

3673:Morgan et al. 1991

3303:concluding remarks

3028:In chapter 101 of

2974:The New York Times

2933:Marilyn vos Savant

2797:Mathematical Games

2665:

2636:

2609:

2485:Minimax solution (

2409:Minimax solution (

1995:probability theory

1930:already determined

1911:

1869:Following Gill, a

1804: : 1 : 0

1502:

787:The New York Times

472:

322:

87:magazine in 1990:

79:Marilyn vos Savant

47:Monty Hall problem

43:

16:Probability puzzle

7190:Let's Make a Deal

7167:

7166:

7073:Aspiration window

7042:Suzanne Scotchmer

6997:Oskar Morgenstern

6892:Donald B. Gillies

6834:Zermelo's theorem

6763:Induction puzzles

6718:Fair cake-cutting

6693:Public goods game

6623:Coordination game

6497:Intransitive game

6427:Forward induction

6309:Pareto efficiency

6289:Gibbs equilibrium

6259:Berge equilibrium

6207:Simultaneous game

6086:BBC News Magazine

5823:on 29 April 2012.

5632:Let's Make a Deal

5527:978-0-00-200791-7

5488:978-0-19-536789-8

5448:Let's make a deal

5175:Let's make a deal

5061:LetsMakeADeal.com

4736:. W. H. Freeman.

4681:on 10 April 2020.

4595:Physical Review A

4429:(December 2005).

4294:Let's make a deal

4284:978-0-8218-4348-2

4233:The Straight Dope

4226:Let's Make a Deal

2984:Let's Make a Deal

2957:The Straight Dope