112:

1073:) can explain variation in genomic architecture among species, e.g. the size of the genome, or the mutation rate. Specifically, larger populations will have lower mutation rates, more streamlined genomic architectures, and generally more finely tuned adaptations. However, if robustness to the consequences of each possible error in processes such as transcription and translation substantially reduces the cost of making such errors, larger populations might evolve lower rates of global

121:

95:

that included both beneficial and deleterious mutations, so that no artificial "shift" of overall population fitness was necessary. According to Ohta, however, the nearly neutral theory largely fell out of favor in the late 1980s, because the mathematically simpler neutral theory for the widespread

929:

is constant (in this sense, the argument in the previous paragraphs can be regarded as based on the “shift model”). This assumption can lead to indefinite improvement or deterioration of protein function. Alternatively, the later “fixed model” fixes the distribution of mutations’ effect on protein

94:

Between then and the early 1990s, many studies of molecular evolution used a "shift model" in which the negative effect on the fitness of a population due to deleterious mutations shifts back to an original value when a mutation reaches fixation. In the early 1990s, Ohta developed a "fixed model"

86:

In this case, the faster rate of neutral evolution in proteins expected in small populations (due to a more lenient threshold for purging deleterious mutations) is offset by longer generation times (and vice versa), but in large populations with short generation times, noncoding DNA evolves faster

1035:: a large product corresponds to adaptive evolution, an intermediate product corresponds to nearly neutral evolution, and a small product corresponds to almost neutral evolution. According to this classification, slightly advantageous mutations can contribute to nearly neutral evolution.

66:

According to the neutral theory of molecular evolution, the rate at which molecular changes accumulate between species should be equal to the rate of neutral mutations and hence relatively constant across species. However, this is a per-generation rate. Since larger organisms have longer

115:

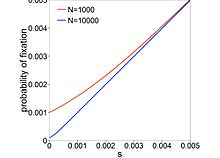

The probability of fixation depends strongly on N for deleterious mutations (note the log scale on the y-axis) relative to the neutral case of s=0. Dashed lines show the probability of fixation of a mutation with s=-1/N. Note that larger populations have more deleterious mutations (not

984:

populations, advantageous mutations are quickly picked up by selection, increasing the mean fitness of the population. In response, the mutation rate of nearly neutral mutations is reduced because these mutations are restricted to the tail of the distribution of selection coefficients.

103:. As more detailed systematics studies started to compare the evolution of genome regions subject to strong selection versus weaker selection in the 1990s, the nearly neutral theory and the interaction between selection and drift have once again become an important focus of research.

82:

substitutions tend to be more neutral, independent of population size, their rate of evolution is correctly predicted to depend on population size / generation time, unlike the rate of non-synonymous changes.

71:, the neutral theory predicts that their rate of molecular evolution should be slower. However, molecular evolutionists found that rates of protein evolution were fairly independent of generation time.

78:

substitutions are slightly deleterious, this would increase the rate of effectively neutral mutation rate in small populations, which could offset the effect of long generation times. However, because

450:

838:

213:

727:

581:

528:

624:

91:

suggesting that a wide variety of molecular evidence supported the theory that most mutation events at the molecular level are slightly deleterious rather than strictly neutral.

657:

1071:

1013:

982:

865:

785:

754:

684:

355:

284:

146:

1033:

952:

927:

907:

887:

474:

328:

308:

257:

237:

124:

The probability of fixation of beneficial mutations is fairly insensitive to N. Note that larger populations have more beneficial mutations (not illustrated).

87:

while protein evolution is retarded by selection (which is more significant than drift for large populations) In 1973, Ohta published a short letter in

909:

can vary between generations but the mean fitness of the population is reset to zero after fixation. This basically assumes the distribution of

1093:

depend on protein abundance (which is responsible for modulating the locus-specific strength of selection), but do so only for high-error-rate

31:

are either so deleterious such that they can be ignored, or else neutral. Slightly deleterious mutations are reliably purged only when their

24:

1500:"Correction for Traverse and Ochman, Conserved rates and patterns of transcription errors across bacterial growth states and lifestyles"

988:

The “fixed model” expands the nearly neutral theory. Tachida classified evolution under the “fixed model” based on the product of

1662:

363:

1117:

287:

44:

787:

populations, these mutations are purged by selection. If nearly neutral mutations are common, then the proportion for which

111:

1683:

1678:

74:

Noting that population size is generally inversely proportional to generation time, Tomoko Ohta proposed that if most

1043:

790:

154:

55:

689:

36:

533:

1085:

483:

586:

54:

in 1973. The population-size-dependent threshold for purging mutations has been called the "drift barrier" by

1688:

1256:

957:

The “fixed model” provides a slightly different explanation for the rate of protein evolution. In large

477:

96:

32:

1046:

has proposed that variation in the ability to purge slightly deleterious mutations (i.e. variation in

1511:

1453:

1200:

1146:

1074:

1261:

286:

is the effective population size. The last term is the probability that a new mutation will become

1224:

1170:

1292:

Ohta T (August 1996). "The current significance and standing of neutral and neutral theories".

120:

1641:

1590:

1539:

1481:

1407:

1358:

1309:

1274:

1216:

1162:

629:

1631:

1621:

1580:

1570:

1529:

1519:

1471:

1461:

1397:

1389:

1348:

1340:

1301:

1266:

1208:

1154:

1079:

1049:

991:

960:

843:

763:

732:

662:

333:

262:

131:

68:

39:. In larger populations, a higher proportion of mutations exceed this threshold for which

1329:"Theoretical study of near neutrality. I. Heterozygosity and rate of mutant substitution"

1247:

Ohta T, Gillespie JH (April 1996). "Development of

Neutral and Nearly Neutral Theories".

1515:

1457:

1204:

1150:

1636:

1609:

1585:

1558:

1534:

1499:

1476:

1441:

1402:

1377:

1353:

1328:

1018:

937:

912:

892:

872:

459:

313:

293:

242:

222:

100:

1672:

757:

79:

40:

1228:

1174:

931:

357:. Kimura’s equation for the probability of fixation in a haploid population gives:

1191:

Ohta T (November 1973). "Slightly deleterious mutant substitutions in evolution".

1393:

1344:

1575:

1559:"Drift Barriers to Quality Control When Genes Are Expressed at Different Levels"

1101:

51:

1504:

Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

1446:

Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

1610:"High Transcriptional Error Rates Vary as a Function of Gene Expression Level"

75:

1524:

1466:

1645:

1594:

1543:

1485:

1305:

1270:

1442:"Evolution of molecular error rates and the consequences for evolvability"

1411:

1362:

1313:

1278:

1220:

1166:

1626:

1094:

58:, and used to explain differences in genomic architecture among species.

28:

1137:

Kimura M (February 1968). "Evolutionary rate at the molecular level".

729:

are called nearly neutral mutations. These mutations can fix in small-

1212:

1158:

1098:

869:

The effect of nearly neutral mutations can depend on fluctuations in

1089:. This is supported by the fact that transcriptional error rates in

1378:"A study on a nearly neutral mutation model in finite populations"

119:

110:

1077:, and hence have higher rates of error. This may explain why

1557:

Xiong K, McEntee JP, Porfirio DJ, Masel J (January 2017).

934:

of population to evolve. This allows the distribution of

445:{\displaystyle P_{fix}={\frac {1-e^{-s}}{1-e^{-sN_{e}}}}}

1608:

Meer KM, Nelson PG, Xiong K, Masel J (January 2020).

1052:

1021:

994:

963:

940:

915:

895:

875:

846:

793:

766:

735:

692:

665:

632:

589:

536:

486:

462:

366:

336:

316:

296:

265:

245:

225:

157:

134:

99:research that flourished after the advent of rapid

1065:

1027:

1007:

976:

946:

921:

901:

881:

859:

832:

779:

748:

721:

678:

651:

618:

575:

522:

468:

444:

349:

322:

302:

278:

251:

231:

207:

140:

1663:The Nearly Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution

954:to change with the mean fitness of population.

1083:has higher rates of transcription error than

833:{\displaystyle P_{fix}\ll {\frac {1}{N_{e}}}}

208:{\displaystyle \rho =ugN_{e}{\bar {P}}_{fix}}

43:cannot overpower selection, leading to fewer

8:

21:nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution

1242:

1240:

1238:

1186:

1184:

889:. Early work used a “shift model” in which

722:{\displaystyle -s\simeq {\frac {1}{N_{e}}}}

576:{\displaystyle P_{fix}={\frac {1}{N_{e}}}}

50:The nearly neutral theory was proposed by

47:events and so slower molecular evolution.

1635:

1625:

1584:

1574:

1533:

1523:

1475:

1465:

1401:

1352:

1260:

1057:

1051:

1020:

999:

993:

968:

962:

939:

914:

894:

874:

851:

845:

822:

813:

798:

792:

771:

765:

740:

734:

711:

702:

691:

670:

664:

637:

631:

608:

599:

588:

565:

556:

541:

535:

523:{\displaystyle |s|\ll {\frac {1}{N_{e}}}}

512:

503:

495:

487:

485:

461:

431:

420:

399:

386:

371:

365:

341:

335:

315:

295:

270:

264:

244:

224:

193:

182:

181:

174:

156:

133:

1015:and the variance in the distribution of

619:{\displaystyle -s\gg {\frac {1}{N_{e}}}}

27:that accounts for the fact that not all

1129:

310:is constant between species, and that

1665:- Perspectives on Molecular Evolution

25:neutral theory of molecular evolution

7:

1327:Ohta T, Tachida H (September 1990).

659:decreases almost exponentially with

35:are greater than one divided by the

1427:The origins of genome architecture

16:Variant of one theory of evolution

14:

1440:Rajon E, Masel J (January 2011).

1429:. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

1510:(29): E4257–E4258. July 2016.

1249:Theoretical Population Biology

1118:History of molecular evolution

496:

488:

187:

1:

1614:Genome Biology and Evolution

1300:(8): 673–7, discussion 683.

290:. Early models assumed that

259:is the generation time, and

1576:10.1534/genetics.116.192567

128:The rate of substitution,

1705:

1394:10.1093/genetics/128.1.183

1345:10.1093/genetics/126.1.219

1039:The "drift barrier" theory

930:function, but allows the

626:(extremely deleterious),

37:effective population size

23:is a modification of the

1086:Saccharomyces cerevisiae

1525:10.1073/pnas.1609677113

1467:10.1073/pnas.1012918108

652:{\displaystyle P_{fix}}

1376:Tachida H (May 1991).

1306:10.1002/bies.950180811

1271:10.1006/tpbi.1996.0007

1067:

1029:

1009:

978:

948:

923:

903:

883:

861:

834:

781:

750:

723:

680:

653:

620:

577:

530:(completely neutral),

524:

470:

446:

351:

324:

304:

280:

253:

239:is the mutation rate,

233:

209:

142:

125:

117:

1068:

1066:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

1030:

1010:

1008:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

979:

977:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

949:

924:

904:

884:

862:

860:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

835:

782:

780:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

751:

749:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

724:

681:

679:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

654:

621:

578:

525:

478:selection coefficient

471:

447:

352:

350:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

325:

305:

281:

279:{\displaystyle N_{e}}

254:

234:

210:

143:

141:{\displaystyle \rho }

123:

114:

97:molecular systematics

33:selection coefficient

1050:

1019:

992:

961:

938:

913:

893:

873:

844:

791:

764:

756:populations through

733:

690:

663:

630:

587:

534:

484:

480:of a mutation. When

460:

364:

334:

314:

294:

263:

243:

223:

155:

132:

1684:Population genetics

1679:Molecular evolution

1516:2016PNAS..113E4257.

1458:2011PNAS..108.1082R

1205:1973Natur.246...96O

1151:1968Natur.217..624K

1627:10.1093/gbe/evz275

1063:

1025:

1005:

974:

944:

919:

899:

879:

857:

830:

777:

746:

719:

676:

649:

616:

573:

520:

466:

442:

347:

320:

300:

276:

249:

229:

205:

138:

126:

118:

1145:(5129): 624–626.

1028:{\displaystyle s}

947:{\displaystyle s}

922:{\displaystyle s}

902:{\displaystyle s}

882:{\displaystyle s}

828:

717:

686:. Mutations with

614:

571:

518:

469:{\displaystyle s}

440:

323:{\displaystyle g}

303:{\displaystyle u}

252:{\displaystyle g}

232:{\displaystyle u}

190:

1696:

1650:

1649:

1639:

1629:

1620:(1): 3754–3761.

1605:

1599:

1598:

1588:

1578:

1554:

1548:

1547:

1537:

1527:

1496:

1490:

1489:

1479:

1469:

1452:(3): 1082–1087.

1437:

1431:

1430:

1425:Lynch M (2007).

1422:

1416:

1415:

1405:

1373:

1367:

1366:

1356:

1324:

1318:

1317:

1289:

1283:

1282:

1264:

1244:

1233:

1232:

1213:10.1038/246096a0

1188:

1179:

1178:

1159:10.1038/217624a0

1134:

1080:Escherichia coli

1072:

1070:

1069:

1064:

1062:

1061:

1034:

1032:

1031:

1026:

1014:

1012:

1011:

1006:

1004:

1003:

983:

981:

980:

975:

973:

972:

953:

951:

950:

945:

928:

926:

925:

920:

908:

906:

905:

900:

888:

886:

885:

880:

866:

864:

863:

858:

856:

855:

840:is dependent on

839:

837:

836:

831:

829:

827:

826:

814:

809:

808:

786:

784:

783:

778:

776:

775:

755:

753:

752:

747:

745:

744:

728:

726:

725:

720:

718:

716:

715:

703:

685:

683:

682:

677:

675:

674:

658:

656:

655:

650:

648:

647:

625:

623:

622:

617:

615:

613:

612:

600:

582:

580:

579:

574:

572:

570:

569:

557:

552:

551:

529:

527:

526:

521:

519:

517:

516:

504:

499:

491:

475:

473:

472:

467:

451:

449:

448:

443:

441:

439:

438:

437:

436:

435:

408:

407:

406:

387:

382:

381:

356:

354:

353:

348:

346:

345:

329:

327:

326:

321:

309:

307:

306:

301:

285:

283:

282:

277:

275:

274:

258:

256:

255:

250:

238:

236:

235:

230:

214:

212:

211:

206:

204:

203:

192:

191:

183:

179:

178:

147:

145:

144:

139:

69:generation times

1704:

1703:

1699:

1698:

1697:

1695:

1694:

1693:

1669:

1668:

1659:

1654:

1653:

1607:

1606:

1602:

1556:

1555:

1551:

1498:

1497:

1493:

1439:

1438:

1434:

1424:

1423:

1419:

1375:

1374:

1370:

1326:

1325:

1321:

1291:

1290:

1286:

1262:10.1.1.332.2080

1246:

1245:

1236:

1199:(5428): 96–98.

1190:

1189:

1182:

1136:

1135:

1131:

1126:

1114:

1053:

1048:

1047:

1041:

1017:

1016:

995:

990:

989:

964:

959:

958:

936:

935:

911:

910:

891:

890:

871:

870:

847:

842:

841:

818:

794:

789:

788:

767:

762:

761:

736:

731:

730:

707:

688:

687:

666:

661:

660:

633:

628:

627:

604:

585:

584:

561:

537:

532:

531:

508:

482:

481:

458:

457:

427:

416:

409:

395:

388:

367:

362:

361:

337:

332:

331:

330:increases with

312:

311:

292:

291:

266:

261:

260:

241:

240:

221:

220:

180:

170:

153:

152:

130:

129:

109:

64:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1702:

1700:

1692:

1691:

1689:Neutral theory

1686:

1681:

1671:

1670:

1667:

1666:

1658:

1657:External links

1655:

1652:

1651:

1600:

1569:(1): 397–407.

1549:

1491:

1432:

1417:

1388:(1): 183–192.

1368:

1339:(1): 219–229.

1319:

1284:

1255:(2): 128–142.

1234:

1180:

1128:

1127:

1125:

1122:

1121:

1120:

1113:

1110:

1060:

1056:

1040:

1037:

1024:

1002:

998:

971:

967:

943:

918:

898:

878:

854:

850:

825:

821:

817:

812:

807:

804:

801:

797:

774:

770:

743:

739:

714:

710:

706:

701:

698:

695:

673:

669:

646:

643:

640:

636:

611:

607:

603:

598:

595:

592:

568:

564:

560:

555:

550:

547:

544:

540:

515:

511:

507:

502:

498:

494:

490:

465:

454:

453:

434:

430:

426:

423:

419:

415:

412:

405:

402:

398:

394:

391:

385:

380:

377:

374:

370:

344:

340:

319:

299:

273:

269:

248:

228:

217:

216:

202:

199:

196:

189:

186:

177:

173:

169:

166:

163:

160:

137:

108:

105:

101:DNA sequencing

63:

60:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1701:

1690:

1687:

1685:

1682:

1680:

1677:

1676:

1674:

1664:

1661:

1660:

1656:

1647:

1643:

1638:

1633:

1628:

1623:

1619:

1615:

1611:

1604:

1601:

1596:

1592:

1587:

1582:

1577:

1572:

1568:

1564:

1560:

1553:

1550:

1545:

1541:

1536:

1531:

1526:

1521:

1517:

1513:

1509:

1505:

1501:

1495:

1492:

1487:

1483:

1478:

1473:

1468:

1463:

1459:

1455:

1451:

1447:

1443:

1436:

1433:

1428:

1421:

1418:

1413:

1409:

1404:

1399:

1395:

1391:

1387:

1383:

1379:

1372:

1369:

1364:

1360:

1355:

1350:

1346:

1342:

1338:

1334:

1330:

1323:

1320:

1315:

1311:

1307:

1303:

1299:

1295:

1288:

1285:

1280:

1276:

1272:

1268:

1263:

1258:

1254:

1250:

1243:

1241:

1239:

1235:

1230:

1226:

1222:

1218:

1214:

1210:

1206:

1202:

1198:

1194:

1187:

1185:

1181:

1176:

1172:

1168:

1164:

1160:

1156:

1152:

1148:

1144:

1140:

1133:

1130:

1123:

1119:

1116:

1115:

1111:

1109:

1107:

1106:S. cerevisiae

1103:

1100:

1096:

1092:

1088:

1087:

1082:

1081:

1076:

1058:

1054:

1045:

1044:Michael Lynch

1038:

1036:

1022:

1000:

996:

986:

969:

965:

955:

941:

933:

916:

896:

876:

867:

852:

848:

823:

819:

815:

810:

805:

802:

799:

795:

772:

768:

759:

758:genetic drift

741:

737:

712:

708:

704:

699:

696:

693:

671:

667:

644:

641:

638:

634:

609:

605:

601:

596:

593:

590:

566:

562:

558:

553:

548:

545:

542:

538:

513:

509:

505:

500:

492:

479:

463:

432:

428:

424:

421:

417:

413:

410:

403:

400:

396:

392:

389:

383:

378:

375:

372:

368:

360:

359:

358:

342:

338:

317:

297:

289:

271:

267:

246:

226:

200:

197:

194:

184:

175:

171:

167:

164:

161:

158:

151:

150:

149:

135:

122:

116:illustrated).

113:

106:

104:

102:

98:

92:

90:

84:

81:

80:noncoding DNA

77:

72:

70:

61:

59:

57:

56:Michael Lynch

53:

48:

46:

42:

41:genetic drift

38:

34:

30:

26:

22:

1617:

1613:

1603:

1566:

1562:

1552:

1507:

1503:

1494:

1449:

1445:

1435:

1426:

1420:

1385:

1381:

1371:

1336:

1332:

1322:

1297:

1293:

1287:

1252:

1248:

1196:

1192:

1142:

1138:

1132:

1105:

1090:

1084:

1078:

1075:proofreading

1042:

987:

956:

932:mean fitness

868:

455:

218:

127:

93:

88:

85:

73:

65:

49:

20:

18:

1102:deamination

760:. In large-

583:, and when

52:Tomoko Ohta

1673:Categories

1124:References

1104:errors in

76:amino acid

1294:BioEssays

1257:CiteSeerX

811:≪

700:≃

694:−

597:≫

591:−

501:≪

422:−

414:−

401:−

393:−

188:¯

159:ρ

136:ρ

29:mutations

1646:31841128

1595:27838629

1563:Genetics

1544:27402746

1486:21199946

1382:Genetics

1333:Genetics

1112:See also

45:fixation

1637:6988749

1586:5223517

1535:4961203

1512:Bibcode

1477:3024668

1454:Bibcode

1412:2060776

1403:1204447

1363:2227381

1354:1204126

1314:8779656

1279:8813019

1229:4226804

1221:4585855

1201:Bibcode

1175:4161261

1167:5637732

1147:Bibcode

1091:E. coli

476:is the

62:Origins

1644:

1634:

1593:

1583:

1542:

1532:

1484:

1474:

1410:

1400:

1361:

1351:

1312:

1277:

1259:

1227:

1219:

1193:Nature

1173:

1165:

1139:Nature

456:where

219:where

107:Theory

89:Nature

1225:S2CID

1171:S2CID

288:fixed

1642:PMID

1591:PMID

1540:PMID

1482:PMID

1408:PMID

1359:PMID

1310:PMID

1275:PMID

1217:PMID

1163:PMID

19:The

1632:PMC

1622:doi

1581:PMC

1571:doi

1567:205

1530:PMC

1520:doi

1508:113

1472:PMC

1462:doi

1450:108

1398:PMC

1390:doi

1386:128

1349:PMC

1341:doi

1337:126

1302:doi

1267:doi

1209:doi

1197:246

1155:doi

1143:217

1097:to

148:is

1675::

1640:.

1630:.

1618:12

1616:.

1612:.

1589:.

1579:.

1565:.

1561:.

1538:.

1528:.

1518:.

1506:.

1502:.

1480:.

1470:.

1460:.

1448:.

1444:.

1406:.

1396:.

1384:.

1380:.

1357:.

1347:.

1335:.

1331:.

1308:.

1298:18

1296:.

1273:.

1265:.

1253:49

1251:.

1237:^

1223:.

1215:.

1207:.

1195:.

1183:^

1169:.

1161:.

1153:.

1141:.

1108:.

1648:.

1624::

1597:.

1573::

1546:.

1522::

1514::

1488:.

1464::

1456::

1414:.

1392::

1365:.

1343::

1316:.

1304::

1281:.

1269::

1231:.

1211::

1203::

1177:.

1157::

1149::

1099:U

1095:C

1059:e

1055:N

1023:s

1001:e

997:N

970:e

966:N

942:s

917:s

897:s

877:s

853:e

849:N

824:e

820:N

816:1

806:x

803:i

800:f

796:P

773:e

769:N

742:e

738:N

713:e

709:N

705:1

697:s

672:e

668:N

645:x

642:i

639:f

635:P

610:e

606:N

602:1

594:s

567:e

563:N

559:1

554:=

549:x

546:i

543:f

539:P

514:e

510:N

506:1

497:|

493:s

489:|

464:s

452:,

433:e

429:N

425:s

418:e

411:1

404:s

397:e

390:1

384:=

379:x

376:i

373:f

369:P

343:e

339:N

318:g

298:u

272:e

268:N

247:g

227:u

215:,

201:x

198:i

195:f

185:P

176:e

172:N

168:g

165:u

162:=

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.