616:

threat manifested in siege towers and earthen ramparts. He was treated respectfully but was imprisoned at

Benevento for almost nine months, and forced to ratify a number of treaties favorable to the Normans. However, according to the Norman accounts, Leo was treated more as an honored guest than as a prisoner, and by no means lacked for comforts, Amatus claims that "they continually furnished him with wine, bread, and all the necessities," and was "protected" by the Normans until he returned to Rome ten months later. According to John Julius Norwich, Leo attempted a long, passive resistance to agreeing to anything for the Normans, and was waiting for an imperial relief army from Germany. In addition, Norwich believes that despite the lack of concrete support until later popes, Leo did eventually acknowledge the Normans as the rulers of the South in order to get a release for his freedom. Meanwhile, Argyros and the Byzantine army were forced to disband and return to Greece via Bari, since their forces were not strong enough to fight the Normans now that the papal forces had been defeated. Argyros may even have been banished from the Empire by Constantine himself.

560:). The Normans went forth to intercept the Papal army near Civitella and prevent its union with the Byzantine army, led by Argyrus. The Normans were short on supplies because of the harvest season, and had fewer men than their enemies, with no more than 3,000 horsemen and 500 infantry against 6,000 horsemen and infantry. Both Amatus' account and William of Apulia agree that the Normans were suffering from hunger and lack of nutrition, and both also add that the Normans forces were in fact so lacking that they, "by the example of the Apostles took the heads of grain, rubbed them in their hands, and ate the kernels," some may have cooked them over the fire beforehand as well. Because of this, the Normans were driven to ask for a truce, but were refused, though there is some disagreement on who the greater enemies of the Normans were in refusing the negotiations, varying between the Lombards, the Germans, and the curia of Pope Leo himself, whom the Normans in fact wished to swear their

620:

Guiscard, who would eventually rise to prominence as the leader of the

Normans in the South. In terms of its implications, the Battle of Civitate had the same long-term political ramifications as had the Battle of Hastings in England and Northern Europe, a reorientation of power and influence into a Latin-Christendom world. Finally, while Leo attempted to maintain an anti-Norman alliance with the Byzantines in hopes of driving them out on religious grounds, the inability of the papal legates to negotiate with the Greek court in addition to Leo's untimely death negated any hope for aid from the Byzantines, except at the command of the Eastern emperor himself. The schism, in this case, worked to the favor of the Normans at least in the political realm.

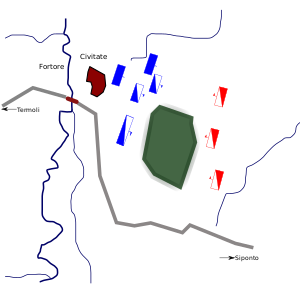

572:, the Slavic infantry), on the left. Other Norman commanders included Peter and Walter, the illustrious sons of Amicus, Aureolanus, Hubert, Rainald Musca, and Count Hugh and Count Gerard, who commanded respectively the Beneventans and the men of Telese, and also Count Radulfus of Boiano. In front of them, the Papal army was divided into two parts, with the heavy Swabian infantry on a thin and long line from the center extending to the right, and the Italian levies amassed in a mob on the left, under the command of Rudolf. Pope Leo was in the city, but his standard, the

68:

518:, offered money to disperse as mercenaries to the Eastern frontiers of the Empire, but the Normans rejected the proposal, explicitly stating that their aim was the conquest of southern Italy. Thus spurned, Argyrus contacted the Pope, and when Leo and his army moved from Rome to Apulia to engage the Normans in battle, a Byzantine army personally led by Argyrus moved from Apulia with the same plan, catching the Normans in a pinch.

627:(1059) marked the recognition of the Norman power in South Italy. There were two reasons for this change in papal politics. First, the Normans had shown themselves to be a powerful (and nearby) enemy, whereas the emperor was a weak (and far off) ally. Second, Pope Nicholas II had decided to cut the bonds between the Roman Church and the Holy Roman emperors, reclaiming for the Roman cardinals the right to elect the pope (see

283:

408:

previously had been approached by both the German

Emperor Henry III and by the Pope previously to swear fealty, finally appealed and submitted to Leo to personally take over the control of the city (as well as lifting a previous excommunication) in 1051. At this point, Benevento was also the border and march land between Rome and the German Empire and the newly established Norman holdings.

240:. The Norman victory over the allied papal army marked the climax of a conflict between the Norman mercenaries who came to southern Italy in the eleventh century, the de Hauteville family, and the local Lombard princes. By 1059 the Normans would create an alliance with the papacy, which included a formal recognition by

589:

sword. These swords were very long and keen, and they were often capable of cutting someone vertically in two! They preferred to dismount and take guard on foot, and they chose rather to die than to turn tail. Such was their bravery that they were far more formidable like this than when riding on horseback.

397:

The Norman advances in southern Italy had alarmed the papacy for many years, though the impetus for the battle itself came about for several reasons. First, the Norman presence in Italy was more than just a case of upsetting the power balance, for many of the

Italian locals did not take kindly to the

424:

He set off to exact punishment for Drogo's death, and after a lengthy siege he finally captured the castrum at which his brother had been killed. He inflicted all sorts of tortures on his brother's murderer and his accomplices, and after a while the anger and grief he felt in his heart were quenched

615:

There is some uncertainty over how this happened. Papal sources say that Leo left

Civitate and surrendered himself to prevent further bloodshed. Other sources including Malaterra indicate that the inhabitants of Civitate handed over the Pope and drove him "out of the gates," after seeing the Norman

593:

The fight with the

Swabians was the main focus of much of the battle, with the Normans attempting to flank the Swabians while Humphrey engaged them. Robert Guiscard, seeing his brother in danger, moved with the left wing to the hill, and succeeded in easing the Swabian pressure, and also displayed

583:

The

Swabians, in the meantime, had moved to the hill, and came into contact with the Norman center and the forces of Humphrey, skirmishing with arrows and archers before entering a general melee. Most likely, this engagement was primarily on foot, as the Germans are often referred to as "taking up

419:

of

Montillaro. Despite the benefit the pope and both Greek and German emperors would have drawn from his murder, it is difficult to speculate beyond Malaterra's report since the details of the murder do not appear in most other sources, particularly the Norman chronicles. Nevertheless, there was

407:

The raiding activities which brought about such hatred also occurred in the see of

Benevento, a deed not emphasized in the Norman chronicles, but for Pope Leo this was the more significant concern in the political instability of the region. In fact, according to Graham Loud, the Beneventians, who

619:

More importantly, the Battle of

Civitate proved to be a turning point in the fortunes of the Normans in Italy, who were able to win a victory despite their differences even among themselves, and solidifying their legitimacy in the process. Not only that, it was the first major victory for Robert

588:

There were proud people of great courage, but not versed in horsemanship, who fought rather with the sword than with the lance. Since they could not control the movements of their horses with their hands they were unable to inflict serious injuries with the lance; however they excelled with the

579:

The battle started with the attack of Richard of Aversa against the Italians on the left with a flanking movement and charge. After moving across the plain, they arrived in front their opponents, who broke formation and fled without even trying to resist. The Normans killed many of them as they

402:

Hatred by the Italians for the Normans has now developed so much and become so inflamed throughout the towns of Italy that scarcely anyone of the Norman race may travel safely on his way, even he be on a devout pilgrimage, for he will be attacked, dragged off, stripped, beaten up, clapped into

496:— answered the call of the Pope, and formed a coalition that moved against the Normans. However, while these forces included troops from almost every great Italian magnate, they did not include forces from Prince of Salerno, who would have gained more than the others from a Norman defeat.

597:

The situation on the center however, remained balanced. Yet thanks to the continued Norman discipline in holding the line against the Swabians, the day was at last decided by the return of Richard's forces from pursuing the Italians, which resulted in the defeat of the Papal coalition.

567:

The two armies were divided by a small hill. The Normans put their horsemen in three companies, with the heavy cavalry of Richard of Aversa on the right, Humphrey with infantry, dismounted knights and archers in the center, and Robert Guiscard, with his horsemen and his infantry (the

370:, "seeking wealth through military service") could not escape the notice of the Christian rulers of Southern Italy, who employed the Normans in their internal wars. The Normans took advantage of this turmoil; in 1030, Rainulf Drengot obtained the

415:, who up to that time had been the nominal war leader of the Normans and Count of Apulia. According to Malaterra's account, the native Lombards were responsible for the plot, and a courtier named Rito committed the deed at the

398:

Norman raiding and wished to respond in kind, regarding them as little better than brigands. An abbot from Normandy, John of Fécamp, for example wrote of such local sentiments in a letter to Pope Leo himself:

507:. At first, the Byzantines, established in Apulia, had tried to buy off the Normans and press them into service within their own largely mercenary army; since the Normans were famous for their

1140:

521:

The Normans understood the danger and collected all available men and formed a single army under the command of the new Count of Apulia and Drogo's eldest surviving brother,

754:

420:

certainly a strong reaction to Drogo's death, with his brother Humphrey taking over the leadership position and in response scoured the countryside for his enemies:

386:

541:

Despite several contemporary sources of the background and lead-up to the battle, the narrative source which gives the most detail of the battle itself is the

631:), thus reducing the importance of the emperor. And in the foreseeable struggle against the Empire, a strong ally was more desirable than a strong enemy.

437:, and asked for aid in curbing the growing Norman power. Initially, substantial aid was refused and Leo returned to Rome in March 1053 with only 700

1145:

411:

The second reason behind the conflict of Civitate was the instability brought about on the Norman side by the murder in unclear circumstances of

1101:

955:

304:

607:

330:

245:

768:

352:

1086:

1135:

308:

377:

After this first success, many other Normans sought to expand into Southern Italy. Among their most important leaders were

430:

1042:

Loud, Graham Alexander. "Continuity and change in Norman Italy: the Campania during the eleventh and twelfth centuries."

580:

retreated and moved further towards the Papal field-camp, before eventually attempting to return to the main engagement.

1044:

456:

But there were others worried about the Norman power, in particular the Italian and Lombard rulers in the south. The

28:

1125:

515:

1150:

612:

After preparing a siege of the town of Civitate itself, the Pope was taken prisoner by the victorious Normans.

293:

229:

172:

1130:

628:

445:(modern day Switzerland), their leader, raised the 700 Swabian knights from the very House out of which the

312:

297:

1039:. Edited by Joseph R. Strayer. Vol. 9. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1989. pp. 159–170.

522:

363:, raided South Italy without much resistance from the Lombard and Byzantine rulers of the affected lands.

213:

155:

553:

95:

67:

473:

1090:

1012:

457:

412:

348:

233:

168:

584:

their swords and shields", William of Apulia adds that this was a part of their German character:

529:, and others of the de Hauteville family, amongst which was Robert, later known under the name of

1028:

968:

748:

526:

163:

981:

976:

378:

20:

973:

De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae comitis et Roberti Guiscardi ducis fratris eius

845:

De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae comitis et Roberti Guiscardi Ducis fratris eius

670:

De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae comitis et Roberti Guiscardi Ducis fratris eius

512:

500:

382:

371:

241:

624:

530:

450:

446:

249:

159:

1009:. Edited by Clifford J. Rogers. Vol. 1. Oxford: University Press, 2010. pp. 402–403.

594:

his personal bravery with the aid of the Calabrians under the command of Count Gerard.

504:

344:

16:

1053 battle between the Normans and a coalition of Swabian, Italian, and Lombard forces

1119:

961:

Amatus of Montecassino (translated by Prescott N. Dunbar and edited by Graham Loud).

465:

461:

206:

985:

1108:

126:

1051:

Loud, Graham Alexander. "How 'Norman' was the Norman Conquest of Southern Italy?"

956:

medievalsicily.com The Medieval Mediterranean Islamic and Norman Sicily (800–1200)

1095:

972:

453:, at the time, included most modern day German-speaking Cantons of Switzerland.

282:

225:

403:

chains, and often indeed will give up the ghost, tormented in a squalid prison.

442:

43:

30:

366:

The availability of this mercenary force (the Normans were famous for being

237:

958:, Chronicles and Narrative Sources with English translations by Graham Loud

355:(Apulia). These warriors had been used to counter the threat posed by the

485:

356:

257:

221:

141:

1024:

The Inception of the Career of the Normans in Italy: Legend and History.

1023:

549:

489:

120:

557:

493:

481:

477:

438:

434:

360:

261:

253:

217:

210:

133:

1007:

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology

905:

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology

1060:

The Age of Robert Guiscard: Southern Italy and the Norman Conquest

508:

469:

381:

members. In short time, the Hauteville created their own state:

276:

623:

After six more years, and three more anti-Norman popes, the

684:

1017:

Histoire de la domination normande en Italie et en Sicilie

205:

was fought on 18 June 1053 in southern Italy, between the

799:

797:

707:

Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Technology

1048:, Vol. 22, No. 4 (December, 1996), pp. 313–343.

548:

To begin with, Leo moved to Apulia, and reached the

1032:, Vol. 23, No. 3. (Jul., 1948), pp. 353–396.

1141:Battles of the Norman conquest of southern Italy

1000:The Norman Conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily

935:The Norman Conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily

892:(Graham Loud Translation ed.). p. 22.

832:(Graham Loud Translation ed.). p. 20.

808:(Graham Loud Translation ed.). p. 19.

586:

422:

400:

60:

1035:Le Patourel, John. "Normans and Normandy," in

1002:. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, 2003.

720:Semper gens normannica prona est ad avaritiam.

499:The Pope had also another friendly power, the

734:

732:

347:in 1017, in a pilgrimage to the sanctuary of

8:

1109:The Normans: their history, arms and tactics

753:: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (

663:

661:

511:. So, the Byzantine commander, the Lombard

311:. Unsourced material may be challenged and

57:

1005:Eads, Valerie. "Civitate, Battle of," in

331:Learn how and when to remove this message

645:

643:

639:

429:Finally, in 1052, Leo met his relative

746:

480:— together with Lombards from Apulia,

72:Battle plan of the Battle of Civitate.

965:. Rochester: The Boydell Press, 2004.

7:

309:adding citations to reliable sources

74:Red: Normans. Blue: Papal coalition.

273:The arrival of the Normans in Italy

525:, as well as the Count of Aversa,

14:

1076:. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

1055:, Vol. 25 (1981), pp. 13–34.

608:Norman conquest of southern Italy

441:infantry. Adalbert II, Count of

281:

66:

23:(1096) of the People's Crusade.

1146:Battles involving the Lombards

1087:The Normans, a European People

246:Norman conquest in south Italy

228:and led on the battlefield by

1:

1096:Breve Chronicon Northmannicum

1037:Dictionary of the Middle Ages

903:Eads. "Civitate, Battle of".

705:Eads. "Civitate, Battle of".

431:Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor

353:Monte Sant'Angelo sul Gargano

576:, was with his allied army.

556:(or Civitella, northwest of

195:6,000, infantry and horsemen

19:Not to be confused with The

1053:Nottingham Medieval Studies

1045:Journal of Medieval History

368:militariter lucrum quaerens

359:, who, from their bases in

343:The Normans had arrived in

1167:

1062:. New York: Longman, 2000.

963:The History of the Normans

860:The History of the Normans

788:The History of the Normans

652:The Age of Robert Guiscard

605:

18:

393:The anti-Norman coalition

178:

149:

114:

78:

65:

1058:Loud, Graham Alexander.

858:Amatus of Montecassino.

786:Amatus of Montecassino.

773:American Legion Burn Pit

449:would later emerge. The

230:Gerard, Duke of Lorraine

173:Gerard, Duke of Lorraine

629:Investiture Controversy

552:River near the city of

1072:Norwich, John Julius.

986:Gesta Roberti Wiscardi

890:Gesta Roberti Wiscardi

830:Gesta Roberti Wiscardi

806:Gesta Roberti Wiscardi

724:Gesta Roberti Wiscardi

591:

545:of William of Apulia.

523:Humphrey of Hauteville

427:

405:

214:Humphrey of Hauteville

209:, led by the Count of

156:Humphrey of Hauteville

150:Commanders and leaders

1136:11th century in Italy

1104:Jersey heritage trust

818:St. Peter's standard.

683:Westenfelder, Frank.

668:Malaterra, Geoffrey.

574:vexillum sancti Petri

349:St. Michael Archangel

96:San Paolo di Civitate

1013:Chalandon, Ferdinand

988:at The Latin Library

843:Geoffrey Malaterra.

769:"Battle of Civitate"

476:and the citizens of

305:improve this section

1091:European Commission

1067:Battaglie Medievali

888:William of Apulia.

828:William of Apulia.

804:William of Apulia.

722:William of Apulia,

458:Prince of Benevento

413:Drogo de Hauteville

224:army, organised by

169:Rudolf of Benevento

40: /

1074:The Other Conquest

1022:Joranson, Einar. "

969:Gaufredo Malaterra

920:The Other Conquest

875:The Other Conquest

685:"Die 700 Schwaben"

203:Battle of Civitate

61:Battle of Civitate

1126:Conflicts in 1053

1069:, pp. 13–36.

1065:Meschini, Marco,

998:Brown, Gordon S.

993:Secondary sources

982:William of Apulia

977:The Latin Library

937:. pp. 73–75.

877:. pp. 94–95.

739:Allen, Brown, R.

385:became, in 1042,

379:Hauteville family

341:

340:

333:

199:

198:

110:

109:

44:41.733°N 15.267°E

21:Battle of Civetot

1158:

939:

938:

930:

924:

923:

915:

909:

908:

900:

894:

893:

885:

879:

878:

870:

864:

863:

855:

849:

848:

840:

834:

833:

825:

819:

816:

810:

809:

801:

792:

791:

783:

777:

776:

765:

759:

758:

752:

744:

736:

727:

717:

711:

710:

702:

696:

695:

693:

691:

680:

674:

673:

665:

656:

655:

647:

513:Catepan of Italy

501:Byzantine Empire

464:, the Counts of

383:William Iron Arm

372:County of Aversa

336:

329:

325:

322:

316:

285:

277:

242:Pope Nicholas II

80:

79:

70:

58:

55:

54:

52:

51:

50:

45:

41:

38:

37:

36:

33:

1166:

1165:

1161:

1160:

1159:

1157:

1156:

1155:

1151:Robert Guiscard

1116:

1115:

1083:

995:

952:

950:Primary sources

947:

942:

932:

931:

927:

917:

916:

912:

902:

901:

897:

887:

886:

882:

872:

871:

867:

857:

856:

852:

842:

841:

837:

827:

826:

822:

817:

813:

803:

802:

795:

785:

784:

780:

767:

766:

762:

745:

738:

737:

730:

718:

714:

704:

703:

699:

689:

687:

682:

681:

677:

667:

666:

659:

649:

648:

641:

637:

625:Treaty of Melfi

610:

604:

539:

531:Robert Guiscard

527:Richard Drengot

451:Duchy of Swabia

447:House of Kyburg

425:by their blood.

395:

387:Count of Apulia

337:

326:

320:

317:

302:

286:

275:

270:

260:, and Count of

250:Robert Guiscard

185:

171:

164:Richard Drengot

162:

160:Robert Guiscard

158:

98:

73:

71:

48:

46:

42:

39:

34:

31:

29:

27:

26:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1164:

1162:

1154:

1153:

1148:

1143:

1138:

1133:

1131:1053 in Europe

1128:

1118:

1117:

1112:

1111:

1107:Patrick Kelly

1105:

1099:

1093:

1082:

1081:External links

1079:

1078:

1077:

1070:

1063:

1056:

1049:

1040:

1033:

1020:

1019:. Paris: 1907.

1010:

1003:

994:

991:

990:

989:

979:

966:

959:

951:

948:

946:

943:

941:

940:

925:

910:

907:. p. 204.

895:

880:

865:

862:. p. 101.

850:

835:

820:

811:

793:

790:. p. 100.

778:

760:

728:

712:

709:. p. 402.

697:

675:

657:

638:

636:

633:

606:Main article:

603:

600:

543:Gesta Wiscardi

538:

535:

505:Constantine IX

460:, Rudolf, the

394:

391:

345:Southern Italy

339:

338:

289:

287:

280:

274:

271:

269:

266:

197:

196:

190:

184:3,000 horsemen

181:

180:

176:

175:

166:

152:

151:

147:

146:

145:

144:

139:

136:

123:

117:

116:

112:

111:

108:

107:

106:Norman victory

104:

100:

99:

94:

92:

88:

87:

84:

76:

75:

63:

62:

49:41.733; 15.267

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1163:

1152:

1149:

1147:

1144:

1142:

1139:

1137:

1134:

1132:

1129:

1127:

1124:

1123:

1121:

1114:

1110:

1106:

1103:

1100:

1097:

1094:

1092:

1088:

1085:

1084:

1080:

1075:

1071:

1068:

1064:

1061:

1057:

1054:

1050:

1047:

1046:

1041:

1038:

1034:

1031:

1030:

1025:

1021:

1018:

1014:

1011:

1008:

1004:

1001:

997:

996:

992:

987:

983:

980:

978:

974:

970:

967:

964:

960:

957:

954:

953:

949:

944:

936:

929:

926:

922:. p. 96.

921:

914:

911:

906:

899:

896:

891:

884:

881:

876:

869:

866:

861:

854:

851:

846:

839:

836:

831:

824:

821:

815:

812:

807:

800:

798:

794:

789:

782:

779:

774:

770:

764:

761:

756:

750:

742:

735:

733:

729:

725:

721:

716:

713:

708:

701:

698:

686:

679:

676:

671:

664:

662:

658:

653:

646:

644:

640:

634:

632:

630:

626:

621:

617:

613:

609:

601:

599:

595:

590:

585:

581:

577:

575:

571:

565:

563:

559:

555:

551:

546:

544:

536:

534:

532:

528:

524:

519:

517:

514:

510:

506:

502:

497:

495:

491:

487:

483:

479:

475:

471:

467:

463:

462:Duke of Gaeta

459:

454:

452:

448:

444:

440:

436:

432:

426:

421:

418:

414:

409:

404:

399:

392:

390:

388:

384:

380:

375:

373:

369:

364:

362:

358:

354:

350:

346:

335:

332:

324:

314:

310:

306:

300:

299:

295:

290:This section

288:

284:

279:

278:

272:

267:

265:

263:

259:

255:

251:

247:

243:

239:

235:

231:

227:

223:

219:

215:

212:

208:

204:

194:

191:

188:

183:

182:

177:

174:

170:

167:

165:

161:

157:

154:

153:

148:

143:

140:

137:

135:

132:

131:

130:

128:

124:

122:

119:

118:

113:

105:

102:

101:

97:

93:

90:

89:

85:

82:

81:

77:

69:

64:

59:

56:

53:

22:

1113:

1073:

1066:

1059:

1052:

1043:

1036:

1027:

1016:

1006:

999:

962:

934:

928:

919:

913:

904:

898:

889:

883:

874:

868:

859:

853:

844:

838:

829:

823:

814:

805:

787:

781:

775:. June 2010.

772:

763:

740:

723:

719:

715:

706:

700:

688:. Retrieved

678:

669:

651:

622:

618:

614:

611:

596:

592:

587:

582:

578:

573:

569:

566:

561:

547:

542:

540:

520:

498:

455:

428:

423:

416:

410:

406:

401:

396:

376:

367:

365:

342:

327:

318:

303:Please help

291:

248:, investing

236:, Prince of

202:

200:

192:

189:500 infantry

186:

125:

115:Belligerents

86:18 June 1053

25:

1102:The Normans

741:The Normans

252:as Duke of

226:Pope Leo IX

47: /

1120:Categories

690:7 February

635:References

537:The battle

474:Archbishop

443:Winterthur

268:Background

129:coalition

1089:, by the

918:Norwich.

873:Norwich.

749:cite book

602:Aftermath

562:fidelitas

503:ruled by

321:June 2017

292:does not

238:Benevento

220:-Italian-

1098:(Latin).

1029:Speculum

650:Graham.

554:Civitate

486:Campania

357:Saracens

258:Calabria

216:, and a

179:Strength

142:Lombards

138:Italians

134:Swabians

91:Location

945:Sources

933:Brown.

672:. xiii.

570:sclavos

550:Fortore

516:Argyrus

509:avarice

490:Abruzzo

439:Swabian

417:castrum

313:removed

298:sources

244:of the

222:Lombard

218:Swabian

207:Normans

121:Normans

35:15°16′E

32:41°44′N

847:. xiv.

558:Foggia

494:Latium

482:Molise

478:Amalfi

472:, the

466:Aquino

435:Saxony

361:Sicily

262:Sicily

254:Apulia

234:Rudolf

232:, and

211:Apulia

103:Result

726:, ii.

470:Teano

127:Papal

755:link

692:2015

492:and

468:and

296:any

294:cite

256:and

201:The

83:Date

975:at

433:in

351:in

307:by

1122::

1026:"

1015:.

984:,

971:,

796:^

771:.

751:}}

747:{{

731:^

660:^

642:^

564:.

533:.

488:,

484:,

389:.

374:.

264:.

193:c.

187:c.

757:)

743:.

694:.

654:.

334:)

328:(

323:)

319:(

315:.

301:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.