267:, a tax levied against goods deemed harmful to society and individuals. For example, "sin taxes" levied against alcohol and tobacco are intended to artificially lower demand for these goods; some would-be users are priced out of the market, i.e. total smoking and drinking are reduced. Products such as alcohol and tobacco have historically been highly taxed and incur excise duties which are one of the categories of indirect tax. Indirect tax (VAT), weighs on the consumer, is not a cause of loss of surplus for the producer, but affects consumer utility and leads to deadweight loss for consumers. Indirect taxes are usually paid by large entities such as corporations or manufacturers but are partially shifted towards the consumer. Furthermore, indirect taxes can be charged based on the unit price of a said commodity or can be calculated based on a percentage of the final retail price. Additionally, indirect taxes can either be collected at one stage of the production and retail process or alternatively can be charged and collected at multiple stages of the overall production process of a commodity.

148:(to society) – in other words, there are either goods being produced despite the cost of doing so being larger than the benefit, or additional goods are not being produced despite the fact that the benefits of their production would be larger than the costs. The deadweight loss is the net benefit that is missed out on. While losses to one entity often lead to gains for another, deadweight loss represents the loss that is not regained by anyone else. This loss is therefore attributed to both producers and consumers.

152:

1596:

376:, the maximum amount that a taxpayer would be willing to forgo in a lump sum to avoid the tax. The deadweight loss can then be interpreted as the difference between the equivalent variation and the revenue raised by the tax. The difference is attributable to the behavioral changes induced by a distortionary tax that are measured by the substitution effect. However, that is not the only interpretation, and

642:

minimally to changes in the price. However, when the supply curve is more elastic, quantity supplied responds significantly to changes in price. In other words, when the supply curve is more elastic, the area between the supply and demand curves is larger. Similarly, when the demand curve is relatively inelastic, deadweight loss from the tax is smaller, comparing to more elastic demand curve.

25:

1585:

389:

276:

505:

decreases. Therefore, buyers and sellers share the burden of the tax, regardless of how it is imposed. Since a tax places a "wedge" between the price buyers pay and the price sellers get, the quantity sold is reduced below the level that it would be without tax. To put it another way, a tax on a good causes the size of market for that good to decrease.

664:

However, when a much higher tax is levied, tax revenue eventually decreases. The higher tax reduces the total size of the market; Although taxes are taking a larger slice of the "pie", the total size of the pie is reduced. Just as in the nail example above, beyond a certain point, the market for a good will eventually decrease to zero.

250:

actually still costs $ 0.10 per nail. Consumers with a marginal benefit of between $ 0.07 and $ 0.10 per nail would then buy nails, even though their benefit is less than the real production cost of $ 0.10. The difference between the cost of production and the purchase price then creates the "deadweight loss" to society.

520:

Government revenue is also affected by this tax: since Amie and Will have abandoned the deal, the government also loses any tax revenue that would have resulted from wages. This $ 40 is referred to as the deadweight loss. It causes losses for both buyers and sellers in a market, as well as decreasing

516:

However, if the government were to decide to impose a $ 50 tax upon the providers of cleaning services, their trade would no longer benefit them. Amie would not be willing to pay any price above $ 120, and Will would no longer receive a payment that exceeds his opportunity cost. As a result, not only

236:

producer of this product would typically charge whatever price will yield the greatest profit for themselves, regardless of lost efficiency for the economy as a whole. In this example, the monopoly producer charges $ 0.60 per nail, thus excluding every customer from the market with a marginal benefit

645:

A tax results in deadweight loss as it causes buyers and sellers to change their behaviour. Buyers tend to consume less when the tax raises the price. When the tax lowers the price received by sellers, they in turn produce less. As a result, the overall size of the market decreases below the optimum

517:

do Amie and Will both give up the deal, but Amie has to live in a dirtier house, and Will does not receive his desired income. They have thus lost amount of the surplus that they would have received from their deal, and at the same time, this made each of them worse off to the tune of $ 40 in value.

659:

than the tax itself; the area of the triangle representing the deadweight loss is calculated using the area (square) of its dimension. Where a tax increases linearly, the deadweight loss increases as the square of the tax increase. This means that when the size of a tax doubles, the base and height

524:

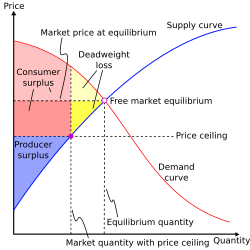

In the graph, the deadweight loss can be seen as the shaded area between the supply and demand curves. While the demand curve shows the value of goods to the consumers, the supply curve reflects the cost for producers. As the example above explains, when the government imposes a tax upon taxpayers,

672:

A deadweight loss occurs with monopolies in the same way that a tax causes deadweight loss. When a monopoly, as a "tax collector", charges a price in order to consolidate its power above marginal cost, it drives a "wedge" between the costs born by the consumer and supplier. Imposing this effective

641:

Price elasticities of supply and demand determine whether the deadweight loss from a tax is large or small. This measures to what extent quantity supplied and quantity demanded respond to changes in price. For instance, when the supply curve is relatively inelastic, quantity supplied responds only

663:

The varying deadweight loss from a tax also affects the government's total tax revenue. Tax revenue is represented by the area of the rectangle between the supply and demand curves. When a low tax is levied, tax revenue is relatively small. As the size of the tax increases, tax revenue expands.

258:

A tax has the opposite effect of a subsidy. Whereas a subsidy entices consumers to buy a product that would otherwise be too expensive for them in light of their marginal benefit (price is lowered to artificially increase demand), a tax dissuades consumers from a purchase (price is increased to

249:

of a product than they otherwise would based on their marginal benefit and the cost of production. For example, if in the same nail market the government provided a $ 0.03 subsidy for every nail produced, the subsidy would reduce the market price of each nail to $ 0.07, even though production

504:

When a tax is levied on buyers, the demand curve shifts downward in accordance with the size of the tax. Similarly, when tax is levied on sellers, the supply curve shifts upward by the size of tax. When the tax is imposed, the price paid by buyers increases, and the price received by seller

237:

less than $ 0.60. The deadweight loss due to monopoly pricing would then be the economic benefit foregone by customers with a marginal benefit of between $ 0.10 and $ 0.60 per nail. The monopolist has "priced them out of the market", even though their benefit exceeds the true cost per nail.

309:

The area represented by the triangle results from the fact that the intersection of the supply and the demand curves are cut short. The consumer surplus and the producer surplus are also cut short. The loss of such surplus is never recouped and represents the deadweight loss.

654:

Taxes may be changed by the government or policymakers at different levels. For instance, when a low tax is levied, the deadweight loss is also small (compared to a medium or high tax). An important consideration is that the deadweight loss resulting from a tax increases

215:

Assume a market for nails where the cost of each nail is $ 0.10. Demand decreases linearly; there is a high demand for free nails and zero demand for nails at a price per nail of $ 1.10 or higher. The price of $ 0.10 per nail represents the point of

512:

of Will's time is $ 80, while the value of a clean house to Amie is $ 120. Hence, each of them get same amount of benefit from their deal. Amie and Will each receive a benefit of $ 20, making the total surplus from trade $ 40.

646:

equilibrium. The elasticities of supply and demand determine to what extent the tax distorts the market outcome. As the elasticities of supply and demand increase, so does the deadweight loss resulting from a tax.

279:

The deadweight loss is the area of the triangle bounded by the right edge of the grey tax income box, the original supply curve, and the demand curve. It is called

Harberger's triangle.

677:. It is important to remember the difference between the two cases: whereas the government receives the revenue from a genuine tax, monopoly profits are collected by a private firm.

287:, shows the deadweight loss (as measured on a supply and demand graph) associated with government intervention in a perfect market. Mechanisms for this intervention include

631:

604:

577:

550:

498:

471:

444:

417:

508:

For example, suppose that Will is a cleaner who is working in the cleaning service company and Amie hired Will to clean her room every week for $ 100. The

1466:

965:

306:

between what consumers pay and what producers receive, and the area of this wedge shape is equivalent to the deadweight loss caused by the tax.

192:

938:

864:

795:

521:

government revenues. Taxes cause deadweight losses because they prevent buyers and sellers from realizing some of the gains from trade.

372:

In modern economic literature, the most common measure of a taxpayer's loss from a distortionary tax, such as a tax on bicycles, is the

361:

and noted that when the

Marshallian demand curve is perfectly inelastic, the policy or economic situation that caused a distortion in

108:

295:, taxes, tariffs, or quotas. It also refers to the deadweight loss created by a government's failure to intervene in a market with

167:

may or may not increase; however, the decrease in producer surplus must be greater than the increase, if any, in consumer surplus.

883:

42:

89:

1620:

579:. Buyers and sellers (Amie and Will) give up the deal between them and exit the market. Thus, the quantity sold reduces from

46:

61:

1157:

232:, producers would charge a price of $ 0.10, and every customer whose marginal benefit exceeds $ 0.10 would buy a nail. A

958:

68:

1451:

1403:

1091:

342:

1635:

1113:

1101:

1096:

1086:

1056:

35:

1531:

1007:

686:

260:

75:

1197:

1066:

334:

1625:

1599:

1496:

1491:

1441:

1314:

1192:

951:

57:

1516:

1476:

1471:

1253:

1224:

1081:

1003:

354:

1461:

1446:

1162:

321:

by pivoting the trend downwards and causing a magnification of losses in the long run but others like

1511:

1431:

1363:

1278:

1172:

1108:

373:

217:

122:

633:. The deadweight loss occurs because the tax deters these kinds of beneficial trades in the market.

1526:

1353:

1202:

1145:

988:

765:

366:

358:

353:

is considered, it can be shown that the

Marshallian deadweight loss is zero if demand is perfectly

229:

184:

172:

1436:

1382:

1309:

1219:

1177:

1167:

1135:

1130:

1076:

1071:

747:

673:

tax distorts the market outcome, and the wedge causes a decrease in the quantity sold, below the

380:

did not use a lump sum tax as the point of reference to discuss deadweight loss (excess burden).

377:

318:

151:

660:

of the triangle double. Thus, doubling the tax increases the deadweight loss by a factor of 4.

1630:

1569:

1557:

1536:

1506:

1368:

1292:

1248:

860:

791:

701:

82:

1521:

1501:

1408:

1358:

1329:

1187:

1152:

1049:

1027:

918:

892:

739:

509:

350:

314:

284:

176:

164:

160:

141:

137:

609:

582:

555:

528:

476:

449:

422:

395:

1589:

998:

346:

939:

Worthwhile

Canadian Initiative "Too much stuff: the deadweight loss from overconsumption"

263:

represents the lost utility for the consumer. A common example of this is the so-called

1564:

1304:

1263:

1182:

974:

691:

362:

923:

906:

1614:

1486:

1386:

1377:

1348:

1334:

1324:

1268:

1032:

1022:

1012:

751:

292:

196:

156:

145:

1456:

1288:

1283:

1017:

848:

727:

204:

1481:

1393:

1273:

1125:

1039:

696:

674:

357:

or supply is perfectly inelastic. However, Hicks analyzed the situation through

322:

296:

288:

200:

188:

24:

392:

The deadweight loss of taxation; the tax increases the price paid by buyers to

1241:

993:

743:

706:

338:

1552:

1319:

1236:

1231:

1044:

388:

303:

129:

1584:

1344:

1339:

1214:

896:

852:

233:

180:

1398:

1297:

1209:

875:

728:"Optimal Concentration and Deadweight Losses in Canadian Manufacturing"

275:

264:

179:

or a service is not produced. Non-optimal production can be caused by

1373:

1258:

1140:

1120:

943:

245:

Conversely, deadweight loss can also arise from consumers buying

1415:

325:

have argued that they do not have a huge impact on the economy.

302:

In the case of a government tax, the amount of the tax drives a

947:

18:

317:

maintain that these triangles can seriously affect long-term

140:

due to production/consumption of a good at a quantity where

349:) demand function differ about deadweight loss. After the

612:

585:

558:

531:

479:

452:

425:

398:

1545:

1424:

981:

49:. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

625:

598:

571:

544:

492:

465:

438:

411:

525:the tax increases the price paid by buyers to

283:Harberger's triangle, generally attributed to

171:Deadweight loss can also be a measure of lost

959:

8:

552:and decreases price received by sellers to

419:and decreases price received by sellers to

966:

952:

944:

121:"DWL" redirects here. For other uses, see

922:

650:How deadweight loss changes as taxes vary

617:

611:

590:

584:

563:

557:

536:

530:

484:

478:

457:

451:

430:

424:

403:

397:

109:Learn how and when to remove this message

907:"A Note on the Concept of Excess Burden"

387:

274:

175:when the socially optimal quantity of a

150:

718:

155:Deadweight loss created by a binding

7:

876:"Three Sides of Harberger Triangles"

824:

822:

820:

818:

816:

47:adding citations to reliable sources

726:Dickson, Vaughan; He, Jian (1997).

446:and the quantity sold reduces from

16:Measure of lost economic efficiency

1522:Microfoundations of macroeconomics

14:

833:. South-Western Cengage Learning.

732:Review of Industrial Organization

259:artificially lower demand). This

1595:

1594:

1583:

905:Lind, H.; Granqvist, R. (2010).

884:Journal of Economic Perspectives

788:Public Finance and Public Policy

23:

859:(5th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

637:Determinants of deadweight loss

34:needs additional citations for

829:N. Mankiw-David Hakes (2012).

790:. New York: Worth Publishers.

1:

924:10.1016/S0313-5926(10)50004-3

668:Deadweight loss of a monopoly

369:, i.e. is a deadweight loss.

911:Economic Analysis and Policy

874:Hines, James R. Jr. (1999).

831:Principles of microeconomics

144:(to society) does not equal

1467:Civil engineering economics

1452:Statistical decision theory

1092:Income elasticity of demand

1652:

1102:Price elasticity of supply

1097:Price elasticity of demand

1087:Cross elasticity of demand

163:always decreases, but the

120:

1578:

810:Lind and Granqvist (2010)

786:Gruber, Jonathan (2013).

687:Excess burden of taxation

261:excess burden of taxation

228:If market conditions are

220:in a competitive market.

187:, a positive or negative

1158:Income–consumption curve

270:

136:is the loss of societal

1492:Industrial organization

857:Principles of Economics

744:10.1023/A:1007714502964

183:pricing in the case of

766:"Negative Externality"

627:

600:

573:

546:

501:

494:

467:

440:

413:

280:

168:

1621:Imperfect competition

1462:Engineering economics

1057:Cost–benefit analysis

628:

626:{\displaystyle Q_{t}}

601:

599:{\displaystyle Q_{e}}

574:

572:{\displaystyle P_{p}}

547:

545:{\displaystyle P_{c}}

495:

493:{\displaystyle Q_{t}}

468:

466:{\displaystyle Q_{e}}

441:

439:{\displaystyle P_{p}}

414:

412:{\displaystyle P_{c}}

391:

313:Some economists like

278:

154:

1279:Price discrimination

1173:Intertemporal choice

897:10.1257/jep.13.2.167

610:

583:

556:

529:

477:

450:

423:

396:

374:equivalent variation

271:Harberger's triangle

218:economic equilibrium

123:DWL (disambiguation)

43:improve this article

1590:Business portal

1527:Operations research

1354:Substitution effect

367:substitution effect

359:indifference curves

230:perfect competition

185:artificial scarcity

173:economic efficiency

1168:Indifference curve

1136:Goods and services

1077:Economies of scope

1072:Economies of scale

623:

596:

569:

542:

502:

490:

463:

436:

409:

329:Hicks vs. Marshall

281:

169:

1636:Welfare economics

1608:

1607:

1570:Political economy

1369:Supply and demand

1249:Pareto efficiency

866:978-0-13-961905-2

797:978-1-4292-7845-4

702:Pareto efficiency

119:

118:

111:

93:

58:"Deadweight loss"

1643:

1598:

1597:

1588:

1587:

1330:Returns to scale

1188:Market structure

968:

961:

954:

945:

928:

926:

900:

880:

870:

835:

834:

826:

811:

808:

802:

801:

783:

777:

776:

774:

772:

762:

756:

755:

738:(5/6): 719–732.

723:

632:

630:

629:

624:

622:

621:

605:

603:

602:

597:

595:

594:

578:

576:

575:

570:

568:

567:

551:

549:

548:

543:

541:

540:

510:opportunity cost

499:

497:

496:

491:

489:

488:

472:

470:

469:

464:

462:

461:

445:

443:

442:

437:

435:

434:

418:

416:

415:

410:

408:

407:

351:consumer surplus

315:Martin Feldstein

285:Arnold Harberger

165:consumer surplus

161:producer surplus

142:marginal benefit

138:economic welfare

114:

107:

103:

100:

94:

92:

51:

27:

19:

1651:

1650:

1646:

1645:

1644:

1642:

1641:

1640:

1611:

1610:

1609:

1604:

1582:

1574:

1541:

1420:

1062:Deadweight loss

999:Consumer choice

977:

972:

935:

904:

878:

873:

867:

847:

844:

842:Further reading

839:

838:

828:

827:

814:

809:

805:

798:

785:

784:

780:

770:

768:

764:

763:

759:

725:

724:

720:

715:

683:

670:

652:

639:

613:

608:

607:

586:

581:

580:

559:

554:

553:

532:

527:

526:

480:

475:

474:

453:

448:

447:

426:

421:

420:

399:

394:

393:

386:

363:relative prices

347:Alfred Marshall

331:

319:economic trends

273:

256:

243:

226:

213:

195:, or a binding

134:deadweight loss

126:

115:

104:

98:

95:

52:

50:

40:

28:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1649:

1647:

1639:

1638:

1633:

1628:

1626:Price controls

1623:

1613:

1612:

1606:

1605:

1603:

1602:

1592:

1579:

1576:

1575:

1573:

1572:

1567:

1565:Macroeconomics

1562:

1561:

1560:

1549:

1547:

1543:

1542:

1540:

1539:

1534:

1529:

1524:

1519:

1514:

1509:

1504:

1499:

1494:

1489:

1484:

1479:

1474:

1469:

1464:

1459:

1454:

1449:

1444:

1439:

1434:

1428:

1426:

1422:

1421:

1419:

1418:

1413:

1412:

1411:

1406:

1396:

1391:

1390:

1389:

1380:

1366:

1361:

1356:

1351:

1342:

1337:

1332:

1327:

1322:

1317:

1312:

1307:

1302:

1301:

1300:

1295:

1286:

1281:

1276:

1271:

1266:

1264:Price controls

1256:

1251:

1246:

1245:

1244:

1239:

1234:

1229:

1228:

1227:

1222:

1212:

1207:

1206:

1205:

1200:

1185:

1183:Market failure

1180:

1175:

1170:

1165:

1160:

1155:

1150:

1149:

1148:

1143:

1133:

1128:

1123:

1118:

1117:

1116:

1106:

1105:

1104:

1099:

1094:

1089:

1079:

1074:

1069:

1064:

1059:

1054:

1053:

1052:

1047:

1042:

1037:

1036:

1035:

1025:

1020:

1010:

1001:

996:

991:

985:

983:

979:

978:

975:Microeconomics

973:

971:

970:

963:

956:

948:

942:

941:

934:

933:External links

931:

930:

929:

902:

891:(2): 167–188.

871:

865:

843:

840:

837:

836:

812:

803:

796:

778:

757:

717:

716:

714:

711:

710:

709:

704:

699:

694:

692:Land value tax

689:

682:

679:

675:social optimum

669:

666:

651:

648:

638:

635:

620:

616:

593:

589:

566:

562:

539:

535:

487:

483:

460:

456:

433:

429:

406:

402:

385:

382:

330:

327:

272:

269:

255:

252:

242:

239:

225:

222:

212:

209:

193:tax or subsidy

117:

116:

31:

29:

22:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1648:

1637:

1634:

1632:

1629:

1627:

1624:

1622:

1619:

1618:

1616:

1601:

1593:

1591:

1586:

1581:

1580:

1577:

1571:

1568:

1566:

1563:

1559:

1556:

1555:

1554:

1551:

1550:

1548:

1544:

1538:

1535:

1533:

1530:

1528:

1525:

1523:

1520:

1518:

1515:

1513:

1510:

1508:

1505:

1503:

1500:

1498:

1497:Institutional

1495:

1493:

1490:

1488:

1485:

1483:

1480:

1478:

1475:

1473:

1470:

1468:

1465:

1463:

1460:

1458:

1455:

1453:

1450:

1448:

1445:

1443:

1442:Computational

1440:

1438:

1435:

1433:

1430:

1429:

1427:

1423:

1417:

1414:

1410:

1407:

1405:

1402:

1401:

1400:

1397:

1395:

1392:

1388:

1387:Law of supply

1384:

1381:

1379:

1378:Law of demand

1375:

1372:

1371:

1370:

1367:

1365:

1364:Social choice

1362:

1360:

1357:

1355:

1352:

1350:

1349:Excess supply

1346:

1343:

1341:

1338:

1336:

1335:Risk aversion

1333:

1331:

1328:

1326:

1323:

1321:

1318:

1316:

1313:

1311:

1308:

1306:

1303:

1299:

1296:

1294:

1290:

1287:

1285:

1282:

1280:

1277:

1275:

1272:

1270:

1269:Price ceiling

1267:

1265:

1262:

1261:

1260:

1257:

1255:

1252:

1250:

1247:

1243:

1240:

1238:

1235:

1233:

1230:

1226:

1225:Complementary

1223:

1221:

1218:

1217:

1216:

1213:

1211:

1208:

1204:

1201:

1199:

1196:

1195:

1194:

1191:

1190:

1189:

1186:

1184:

1181:

1179:

1176:

1174:

1171:

1169:

1166:

1164:

1161:

1159:

1156:

1154:

1151:

1147:

1144:

1142:

1139:

1138:

1137:

1134:

1132:

1129:

1127:

1124:

1122:

1119:

1115:

1112:

1111:

1110:

1107:

1103:

1100:

1098:

1095:

1093:

1090:

1088:

1085:

1084:

1083:

1080:

1078:

1075:

1073:

1070:

1068:

1065:

1063:

1060:

1058:

1055:

1051:

1048:

1046:

1043:

1041:

1038:

1034:

1031:

1030:

1029:

1026:

1024:

1021:

1019:

1016:

1015:

1014:

1011:

1009:

1008:non-convexity

1005:

1002:

1000:

997:

995:

992:

990:

987:

986:

984:

980:

976:

969:

964:

962:

957:

955:

950:

949:

946:

940:

937:

936:

932:

925:

920:

916:

912:

908:

903:

898:

894:

890:

886:

885:

877:

872:

868:

862:

858:

854:

850:

849:Case, Karl E.

846:

845:

841:

832:

825:

823:

821:

819:

817:

813:

807:

804:

799:

793:

789:

782:

779:

767:

761:

758:

753:

749:

745:

741:

737:

733:

729:

722:

719:

712:

708:

705:

703:

700:

698:

695:

693:

690:

688:

685:

684:

680:

678:

676:

667:

665:

661:

658:

649:

647:

643:

636:

634:

618:

614:

591:

587:

564:

560:

537:

533:

522:

518:

514:

511:

506:

485:

481:

458:

454:

431:

427:

404:

400:

390:

383:

381:

379:

375:

370:

368:

364:

360:

356:

352:

348:

344:

340:

336:

328:

326:

324:

320:

316:

311:

307:

305:

300:

298:

297:externalities

294:

290:

286:

277:

268:

266:

262:

253:

251:

248:

240:

238:

235:

231:

223:

221:

219:

210:

208:

206:

202:

198:

197:price ceiling

194:

190:

186:

182:

178:

174:

166:

162:

158:

157:price ceiling

153:

149:

147:

146:marginal cost

143:

139:

135:

131:

124:

113:

110:

102:

91:

88:

84:

81:

77:

74:

70:

67:

63:

60: –

59:

55:

54:Find sources:

48:

44:

38:

37:

32:This article

30:

26:

21:

20:

1532:Optimization

1517:Mathematical

1477:Experimental

1472:Evolutionary

1457:Econometrics

1315:Public goods

1289:Price system

1284:Price signal

1198:Monopolistic

1067:Distribution

1061:

982:Major topics

917:(1): 63–73.

914:

910:

888:

882:

856:

853:Fair, Ray C.

830:

806:

787:

781:

771:February 11,

769:. Retrieved

760:

735:

731:

721:

671:

662:

657:more quickly

656:

653:

644:

640:

523:

519:

515:

507:

503:

371:

332:

312:

308:

301:

289:price floors

282:

257:

246:

244:

227:

214:

205:minimum wage

170:

133:

127:

105:

96:

86:

79:

72:

65:

53:

41:Please help

36:verification

33:

1482:Game theory

1447:Development

1394:Uncertainty

1274:Price floor

1254:Preferences

1193:Competition

1163:Information

1126:Externality

1109:Equilibrium

1050:Transaction

1028:Opportunity

989:Aggregation

697:Optimal tax

343:Marshallian

323:James Tobin

201:price floor

189:externality

1615:Categories

1512:Managerial

1432:Behavioral

1305:Production

1242:Oligopsony

1082:Elasticity

994:Budget set

713:References

707:Tax choice

341:) and the

339:John Hicks

203:such as a

69:newspapers

1553:Economics

1425:Subfields

1320:Rationing

1237:Oligopoly

1232:Monopsony

1220:Bilateral

1153:Household

1004:Convexity

752:150473969

130:economics

1631:Scarcity

1600:Category

1546:See also

1437:Business

1409:Marginal

1404:Expected

1345:Shortage

1340:Scarcity

1215:Monopoly

1121:Exchange

1033:Implicit

1023:Marginal

855:(1999).

681:See also

384:Taxation

335:Hicksian

234:monopoly

224:Monopoly

211:Examples

181:monopoly

99:May 2024

1558:Applied

1537:Welfare

1399:Utility

1359:Surplus

1298:Pricing

1210:Duopoly

1203:Perfect

1146:Service

1114:General

1018:Average

355:elastic

265:sin tax

241:Subsidy

83:scholar

1383:Supply

1374:Demand

1310:Profit

1178:Market

1040:Social

863:

794:

750:

365:has a

159:. The

85:

78:

71:

64:

56:

1502:Labor

1487:Green

1259:Price

1141:Goods

1131:Firms

879:(PDF)

748:S2CID

378:Pigou

345:(per

337:(per

304:wedge

90:JSTOR

76:books

1416:Wage

1325:Rent

1293:Free

1045:Sunk

1013:Cost

1006:and

861:ISBN

792:ISBN

773:2012

333:The

293:caps

247:more

191:, a

177:good

62:news

1507:Law

919:doi

893:doi

740:doi

606:to

473:to

254:Tax

199:or

128:In

45:by

1617::

915:40

913:.

909:.

889:13

887:.

881:.

851:;

815:^

746:.

736:12

734:.

730:.

299:.

291:,

207:.

132:,

1385:/

1376:/

1347:/

1291:/

967:e

960:t

953:v

927:.

921::

901:.

899:.

895::

869:.

800:.

775:.

754:.

742::

619:t

615:Q

592:e

588:Q

565:p

561:P

538:c

534:P

500:.

486:t

482:Q

459:e

455:Q

432:p

428:P

405:c

401:P

125:.

112:)

106:(

101:)

97:(

87:·

80:·

73:·

66:·

39:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.