27:

1088:. Many ancient tribes in pre-dynastic China shared a common belief in the spiritual world. The spirits were thought to possess divine powers. As such, they were able to intervene in and dictate the lives of the living realm's beings. That led to the necessity of direct communication with the spirits, through means of mystics. A group of specified individuals, known as shamans, arose and took responsibility for conducting their respective tribe's religious rituals. The cultures in the future heartland of the Shang dynasty had practiced sacrifices and funerals. In many regions of China,

183:

114:

1008:). This is no different from the method by which today’s children practice writing (xízì 習字). Shedding light on the educational circumstances of three thousand years ago, it is of the utmost interest. Furthermore, interspersed within the columns written by the trainee are finely written graphs identical to those of the model, where presumably the attendant teacher took up the knife. Examples include the 辰, 午 and 申 of the second line, and the 卯, 己 and 辛 of the third.

900:

purpose, including an ancestral temple, a tower, and a guesthouse intended to store sacrifices. Wu Ding seemed to have played a role in these activities, as texts reveal that the king distributed to the patron materials like prisoners and special grains for ancestor worship. Other relatives, ranging from cousins to children, were commissioned by the patron to participate in religious activities. According to the inscriptions collected, these people included:

777:

Ding who was authorized to conduct his own religious activities. According to interpretations of oracle bone inscriptions, the prince led his own entourage of diviners, as well as relatives who were entrusted to conduct religious activities during his absence. His divinations, numbered up to 537 written texts, seemed to address only some individuals worshipped by the royal family at the capital city. In particular, the divinations concern extensively on

1319:

Some men who have not complied with virtue will yet not acknowledge their offences, and when Heaven has by evident tokens charged them to correct their conduct, they still say, "What are these things to us?" Oh! our

Majesty's business is to care reverently for the people. And all your ancestors were the heirs of the kingdom by the gift of Heaven; in attending to the sacrifices, be not so excessive in those to your father.'

1064:

1204:

611:) denotes priests. Therefore, there is a possibility that the "wu" during the Shang dynasty were originally people migrating from Inner Asia, and that they were non-shamanic priests. Mair supposed that the "wu" are better understood as people able to communicate with the spiritual world through art and sacrifices rather than shaman's practices like stance and mediation.

934:, the writing system developed by the Shang dynasty, is thoroughly complex. Literacy among scribes was considered very important, for the purpose of divination and record rituals. Robert Bagley articulated saying that Shang literacy was tied to a maximal extreme, but he also noted that the process of acquiring full literacy for Shang scribes is not understood.

191:

process typically included cleaning meat out of bones, scraping and polishing the surfaces, anointing with blood, drilling holes through the bones, applying heat and inscribing characters. Often, divinatory inscriptions would include various kinds of information, and in many examples the diviner's name was written down.

776:

Aside from the central government at Yin, the Shang religion was also practiced in other areas of the state. Over 1000 oracle bones, many of which bear divinatory inscriptions, were excavated at

Huayuanzhuang, near the historical site of Yin. The initial owner was a royal relative, a close kin of Wu

1018:

In a work by

Matsumaru Michio, 156 occurrences of Shang date tables were studied and classified into three groups according to the degree of writing competence. The most finely texts of one group were proposed to be models for learning, while those from the other two categories were student copies.

917:

It is believed that common people during this period may have taken part in popular religion. There are possibilities that the populace might have participated in seasonal festivals and sacrificial offerings. Commoners might as well have been involved in religious activities carried out by regional

1375:

He blindly discards his paternal and maternal uncles who are still alive and fails to employ them. Thus, indeed, the vagabonds of the four quarters, loaded with crimes—these he honors, these he exalts, these he trusts, these he enlists, these he takes as high officials and dignitaries, to let them

1237:

Then he fasted, cut off his hair and nails. Tang, in a horse-drawn carriage, dressed as a sacrificial victim, and went to a forest of mulberry trees in which an altar was built. There he prayed, asking about which of his wrongdoing had led to calamities. It is told that a heavy rain fell when Tang

1022:

Literacy and engraving techniques are distinguished from one another; therefore, some have questioned Guo Moruo's interpretation of the bones. In replying to Guo's remarks on the training, Zhang

Shichao commented that the former's theory was flawed since crooked writing was not enough to prove the

190:

On divinatory ceremonies, the Shang king was assisted by a number of diviners (多卜), possibly directed by a supervisor (官占). They were tasked with heating the oracle bones which contain questions to Shang ancestors, and interpreting the cracks made by the heat to obtain the response. The divination

1318:

He delivered accordingly a lesson to the king, saying, 'In its inspection of men below, Heaven's first consideration is of their righteousness, and it bestows on them (accordingly) length of years or the contrary. It is not Heaven that cuts short men's lives; they bring them to an end themselves.

614:

However, various oracle bone examples point out the presence of rituals involving the Shang king which were related to "invocation". In some ceremonies, the deities would be present as "guests", and the Shang king was the person who acted as "host". Hosting rituals took place at numerous temples,

899:

Many inscriptions excavated at

Huayuanzhuang were made in Rong, a conquered place. According to interpretations, the prince began to settle there, organized ancestral spirit tablets in new worshipping places, and conducted offerings. He also commissioned additional constructions serving for this

60:

that focused on worshipping spiritual beings. The dynasty developed a bureaucracy specialized in practicing rituals, divided into several positions tasked with performing different aspects of the religion. Usually, the head practitioners were the Shang king and other members of the royal family.

869:

Other than divinations, this royal patron also participated in sacrificial rituals and establishing religious centers in his assigned estate. Mentions of sacrifice in his inscriptions suggest the presence of staff entrusted to conduct sacrifice on his behalf. In some occasions, he directly made

154:

The Shang king's level of involvement strongly relates to his influence and gain sovereignty over remote polities. Over time, the Shang dynasty gradually expanded and increased interaction with tribes and chiefdoms. Its religion possibly adopted gods worshipped by those polities into its own

1228:

about Tang's religious sentiments. For seven years after Tang's accession to the throne, (1766−1760 BCE according to the traditional chronology), there was a great drought accompanied by famine. It was suggested at last that a human being be offered in a sacrificial ritual to the

234:. Diviners therefore were interpreted as interchanging groups. In modern studies of oracle bone inscriptions, various findings have challenged the hypothesis; a new classification is established. Diviners are classified into groups named after the most active diviner among them.

201:

BCE to 1046 BCE, several distinct scribal groups existed and often intermingled. Their style, calligraphy and inscriptional contents are comparably different. The 20th century classification method by

Chinese scholars describes the diviners as two groups, referred to as the

104:

recreated a typical Shang ritual involving different practitioners. Based on actual inscriptions regarding Wu Ding's attempts to cure toothache using rituals. His account serves as a critical demonstration of a regular work done by religious figures in the Shang capital.

1413:

Japanese scholars used the designation Ib for a group of diviners (formerly called the Royal Family Group) that Dong had originally interpreted as a period-IVb revival of Wu Ding-era practices, but are now assigned to period I groups including Shī 師/Duī

1264:

The former king kept his eye continually on the bright requirements of Heaven, and so he maintained the worship of the spirits of heaven and earth, of those presiding over the land and the grain, and of those of the ancestral temple; all with a sincere

470:

or not. Robert Eno argued that communication with the deified spirits was done via sacrifices and technical manipulation of bones, and therefore could not be shamanism since it did not involve direct encounter with the spirits. Against Eno's suggestion,

486:", though some have expressed disagreement towards this translation. Some scholars questioned about its true meaning, and whether it actually referred to a shaman or another kind of practitioner. According to G. Boileau, four meanings of this

125:

worshipped by the Shang, aside supernatural beings, were spirits of deceased ancestors. The reigning Shang king would be responsible for communicating with all the spirits for the state's welfare and successes. He communicated through means of

91:

support the view of active shamans in the court, while others claim that the dynasty did not actually adopted shamanism in ceremonies. In particular situations, the Shang king and royal members acted in a shamanic way when hosting rituals.

674:) is interpreted to be semantically similar to a Shang ritual which involved the king calling out the spirits. Because this ritual was shown to be a prerogative of the Shang king, Childs-Johnson believed that he acted as a shaman-priest.

134:. The Shang kings usually gave the final prognostications about upcoming events, by interpreting the patterns on heated bones (ox scapulae, turtle plastrons, etc.). Predicted events were intended to last a full Shang week of ten days (

1075:

Before the dawn of organized states in China, the area was inhabited by various tribal confederations. Each of the tribes practiced its own system of beliefs. The religious beliefs in prehistoric China were based on ideas of

718:

as the reference celestial object. The Shang seemed to regard eclipses as ominous events forecasting terrible future, such as the demise and death of a king. Oracle bones of Wu Ding's reign record five lunar eclipses dated

709:

The role of astronomers and astrologers in the religion is incompletely understood but was possibly important. The shape of Shang characters for religious figures imply a complex comprehension and interpretation of the

1334:, who in traditional texts served Wu Ding. In Fu's counsels given to his king, too much sacrifices would be harmful and counterproductive, as they were not respectful to the spirits, and therefore brought disorder.

1238:

had not finished his prayer, saving the

Chinese people from further disasters. The story of Tang praying to the gods is used to praise him as a figure who earnestly obey Heaven, or alternatively, the Shang high god

989:

The content consists of the gānzhī for days 1 to 10 engraved repeatedly. In the fourth line of text, the graphs are finely written and orderly, as though engraved by a teacher (xiānshēng 先生) to serve as a model

615:

each housing a single or a group of spirits. Some scholars understand the "guest" rituals to have featured the kings as ceremonial hosts uniquely equipped to "hear" the spiritual messages in religious events.

79:, the first instances of recorded rituals have been documented by the Shang people. Various positions were employed to either directly practice the religion or to provide related support. The involvement of

866:, along with approximately 20 other spirits. Wu Ding and Fu Hao were two living relatives mentioned in the Huayuanzhuang inscriptions, appearing to be in regular contact with the prince through meetings.

2696:

1039:(商) which coincides with the Shang dynasty's name but in the context has a different meaning. The character was speculated to denote a form of dance. There are inscriptions about continuing to perform

981:

Scholars have interpreted a large number of oracle bone inscriptions and suggested that a method of training scribes through repetitive practice of imitating model texts. In a 1937 annotated catalog,

978:‘to enter the xué’), but these examples could equally be verbs. Generally, it has been argued that the use of this word in oracle bone inscriptions definitely refers to a kind of scribal training.

1300:

remonstrated with him, counselling him to made religious reforms by reducing offerings to Shang ancestral spirits, as to correct the meaning of sacrifices. Zu Ji's speech was recorded in the

1023:

action of learning written language. He claimed that the trainees might have been actually literate at that time, and the texts might be their attempts in learning writing techniques.

1715:

541:

The wu is seen as offering a sacrifice of appeasement but the inscription and the fact that this kind of sacrifice was offered by other persons (the king included) suggests that the

1180:

When Qi conquered Song in 286 BCE, the Shang religion ceased to be practiced formally, although the spirits of Shang kings were still revered in later imperial dynasties of China.

1135:

Around 1046 BCE, the Shang dynasty collapsed, and a new Zhou dynasty commenced its course. King Wu of Zhou, the first king of the new royal family, enfranchised the Shang prince

1341:

as a ruler who completely neglected religious affairs, especially sacrifices. Zhou people interpreted his actions as one of the reasons why his regime collapsed eventually. The

756:

The Shang rituals featured and necessitated the use of music. Divination was conducted to determine the kind of music going to be performed, usually dance. A number of dancers (

3438:

Nelson, Sarah M.; Matson, Rachel A.; Roberts, Rachel M.; Rock, Chris; Stencel, Robert E. (2006). "Archaeoastronomical

Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang".

3371:

Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (2023), "Continuation of

Metamorphic Imagery and Ancestor Worship in the Longshan Culture", in Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth; Major, John S. (eds.),

1188:

Many

Chinese dynasties that ruled after the Shang composed various texts that mention alleged Shang religious practitioners. The Chinese classics of the Zhou dynasty, the

781:, who was mentioned in Wu Ding's divinations as the king's mother. Divination concerning this deceased ancestor are plentiful, and can be demonstrated through examples:

167:(earth), which strongly exemplifies outside influence. By worshipping both his own and others' gods, the king would be able to maintain suzerainty over the regions.

141:

The Shang monarchs also acted as organizers of ceremonies. When a king died, his successor would be responsible for giving him a proper burial ritual. An example is

3444:

69:. The Shang religion also existed outside of the capital, being practiced by royal patrons who were entrusted to govern different regions within the Shang state.

1453:

Some prehistoric Chinese cultures produced artifacts that bear the "AZ" motif, which represented some kind of a "High God" similarly to the Shang dynasty's Di.

2641:

151:. His role in this aspect was not restricted to deceased predecessors, as he also directed burials and rituals for relatives who died during his reign.

214:

during the 12th century BCE, the groups had experienced periods of high activity along with times in which they were not favored. Shang kings such as

733:

Chinese literature after the Shang dynasty mentioned Shang astronomers such as Wuxian, who allegedly composed a star map. The Grand Historian of the

2653:

1471:

According to David Pankenier, the Zhou overlord Ji Fa defeated the last Shang king on 20th January, 1046 BCE, marking the end of the old regime.

559:

He follows (being brought, presumably, to Shang territory or court) the orders of other people; he is perhaps offered to the Shang as a tribute.

3496:

950:

could be written as both a verb and a noun. Some inscriptions reveal that when the word is used in collocation with "大", the resulting phrase "

1280:

Other than that, the ancient Chinese tradition additionally say of later Shang kings who were given counsels by their ministers. For the king

1150:) kept the old Shang religious practices by revering Shang spirits. Early Zhou oracle bones found in Zhouyuan contain inscriptions concerning

3410:

3352:

3288:

3270:

3252:

3217:

3149:

2987:

2773:

2685:

2559:

2413:

2386:

2298:

170:

Within the royal palaces at Yin, several royal members apart from the ruler featured themselves as head priests. The most active of them was

985:

examined the piece CB: 1468=HJ: 18946 which contains the information of sexagenary days and noticed such "learning" pattern. Guo commented:

2801:

Didier, John C. (2009). "In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200".

1019:

However, the author did not make any claims about whether the students in that case were acquiring literacy or learning engraving skills.

571:

could be deciphered in other ways apart from the commonly used speculation. Victor H. Mair, researching into the connection between early

3082:. Volume V, Book II. The Soul and Ancestral Worship: Part II. Demonology. — Part III. Sorcery. Taipei: Brill- Literature House (reprint).

1296:

when a wild pheasant was spotted on a sacrificial vessel. The king interpreted it as a negative sign from the gods, but his eldest son

3084:

The author argued that "wu" in Chinese and "shaman" in Western languages are culturally different, and not compatible for translation.

946:) has been identified. Two plastrons inscribed during Wu Ding's regnal era, HJ: 8304 and HJ: 16406, are interpreted and indicate that

3428:

3392:

3009:

2840:

2630:

714:. Shang cosmology concentrated on the squared area defined by the Pole's surrounding stars at the time of the Shang, probably using

100:

Oracle bone inscriptions reveal a considerable number of individuals associated with the Shang religion. In an imaginative account,

1095:

Archaeological evidence indicates that music culture developed in China from a very early period. Excavations in Jiahu Village in

1050:

It is generally believed that the Shang might have had some kinds of institutionalized training locations for religious teaching.

535:

It could be either the name for a function or the name of a people (or an individual) coming from a definite territory or nation;

1031:

The records belonging to the royal relative at Huayuanzhuang indicate a form of dance schooling. In five inscriptions, the word

538:

The wu seems to have been in charge of some divinations, (in one instance, divination is linked to a sacrifice of appeasement);

2980:

Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin. English translation by Mark Caltonhill and Jeff Moser

618:

Oracle bone inscriptions record instances in which the king played the major role, as demonstrated by the two examples below:

2542:

Keightley, David N. (1999), "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.),

1196:

138:). In many cases, divinations made by the kings (indicated by bone inscribers) predicted ominous and unfortunate situations.

1169:. Weizi and his descendants adhered to the Shang religion throughout the Song state's existence. Shu Yi, a high official of

1158:

84:

57:

20:

2877:

Michio, Matsumaru (2003). "Jieshao yi pian sifang feng ming keci gu" (悦紹М片四方風名刻辭骨)". In Wang Yuxin; Song Zhenhao (eds.).

30:

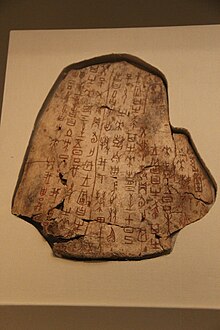

A Shang religious text written by the Bīn 賓 group of diviners from period I, corresponding to the reign of King Wu Ding (

3401:

Zhao, Chunqing (2013), "The Longshan culture in central Henan province, c.2600–1900 BC", in Underhill, Anne P. (ed.),

2522:

Origins of Chinese Political Philosophy: Studies in the Composition and Thought of the Shangshu (Classic of Documents)

482:(巫, rendered as the shape of a "plus" sign in oracle bone inscriptions). The word has been generally translated as "

3235:

26:

768:). Often, dancers would perform in religious sanctuaries, including natural landscapes such as the Yellow River.

1284:, whose actual reign produced the majority of Shang oracle bone inscriptions, was portrayed a character in the

651:

day: The king will carry out the rite of invocation to Father Xīn with sheep, pigs you-buckets of millet wine.

2517:

1220:

as a religious and perspicacious figure in Chinese history. There is a story recorded by both the philosopher

2868:

Smith, Adam (2011a). "The Evidence for Scribal Training at Anyang". In Li Feng; David Prager Branner (eds.).

1404:

Only the main periods of activity are shown here. The diviner groups often overlapped with adjoining reigns.

1310:高宗肜日,越有雊雉。祖己曰:「惟先格王,正厥事。」乃訓于王。曰:「惟天監下民,典厥義。降年有永有不永,非天夭民,民中絕命。民有不若德,不聽罪。天既孚命正厥德,乃曰:『其如台?』嗚呼!王司敬民,罔非天胤,典祀無豐于昵

3038:

von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1995). "Reflections of the Political Role of Spirit Mediums in Early China: The

2829:

Smith, Adam (8 August 2019). "The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Origin of the Chinese Writing System".

2476:

1161:, but was defeated and killed by the royal army. The Zhou dynasty enfeoffed another Shang prince, titled

914:

Further than Huayuanzhuang, texts from Daxinzhuang, 250 kilometers apart from Yin, have also been found.

3480:

Divination and Power: a Multiregional View of the Development of Oracle Bone Divination in Early China

3230:(2004). "Anyang Writing and the Origin of the Chinese Writing System". In Houston, Stephen D. (ed.).

2803:

1314:

On the day of the supplementary sacrifice of Gaozong, there appeared a crowing pheasant. Zu Ji said,

174:, the secondary queen. She was among the most frequently mentioned names in Shang divinatory texts.

2879:

Jinian Yinxu jiaguwen faxian yibai zhou nian guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji (紀念殷墟⭢骨文發現М百周年國際學術研討會)

1444:

Authors differ on which of these modern characters should be used in reading the oracle bone glyph.

1221:

182:

450:), which detail the religious calendar, scholars have been able to create a reconstruction of the

3155:

3105:

3063:

2966:

2925:

2728:

931:

888:

some pen-raised cattle, our lord should do it himself; (he) ought not invite (anyone else). Used.

430:

42:

19:

This article is about specified people who practiced the Shang religion. For the religion, see

3424:

3406:

3388:

3348:

3284:

3266:

3248:

3213:

3145:

3113:

3075:

3005:

2983:

2836:

2769:

2681:

2626:

2555:

2409:

2382:

2294:

1343:

1247:

1104:

1085:

475:

claimed that the absence of shamanism would make understandings of Shang religion incomplete.

2851:

2830:

2362:

Gao Guangren; Shao Wangping, eds. (1986). "Zhongguo shiqian shidai de guiling yu quansheng".

1200:

as well as others describe these figures as illustrious models for righteousness and virtue.

3380:

3332:

3302:

3135:

3097:

3055:

3026:

3020:

2958:

2937:

2913:

2761:

2740:

2718:

2708:

2673:

2618:

2581:

2547:

2403:

2188:

1208:

1108:

1068:

472:

324:

147:

88:

3323:

Wang, Haicheng (2007), "Writing and the State in Early China in Comparative Perspective",

2997:

2179:

Wang, Haicheng (2007), "Writing and the State in Early China in Comparative Perspective",

101:

2151:

3299:

The first known Chinese calendar: A reconstruction by the synchronic evidential approach

999:). The rest are crooked and inferior, as though written by someone learning to engrave (

186:

Ox scapula recording divinations by a diviner named Zhēng 爭 in the reign of King Wu Ding

2904:

Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (1995). "The Ghost Head Mask and Metamorphic Shang Imagery".

1173:

around 600 BCE, was a direct descendant of the Shang. He owned a bronze artifact named

1112:

600:

572:

389:

223:

2823:

Volume III: Terrestrial and Celestial Transformations in Zhou and Early-Imperial China

2817:

Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China

2612:

795:: Our lord, staying overnight in Rong, at dawn will kill some pen-raised cattle (for)

552:

appears. Nevertheless, the nature of the link is not known, because the status of the

3490:

3227:

3159:

3067:

2753:

2732:

1293:

1216:

1162:

1096:

568:

467:

160:

46:

2970:

2822:

2816:

2810:

2697:"The Anyang Xibeigang Shang royal tombs revisited: a social archaeological approach"

1435:

in his Period I, but no inscriptions can be reliably assigned to pre-Wu Ding reigns.

2785:

Old Sinitic Myag, Old Persian Magus, and English 'Magician'"(Early China 15, 27-47)

1432:

1338:

1190:

1166:

1140:

131:

66:

2551:

1203:

155:

pantheon, and could also have associated the polities themselves with Shang gods.

113:

3207:

516:"a living human being, possibly the name of a person, tribe, place, or territory"

3002:

Sources of Shang history : the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China

2835:. MPRL – Proceedings. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften.

2498:

734:

596:

399:

248:

2585:

3336:

3059:

2962:

2941:

2917:

2622:

2455:

2192:

1170:

711:

576:

451:

127:

1154:, one of the last Shang kings who used to be worshipped by the Shang people.

745:

that he took Wuxian's celestial map as a source to identify the residence of

3376:

2758:

Calendars and Years II: Astronomy and time in the ancient and medieval world

2569:

1225:

1089:

982:

910:

Zi Hu and Zi Bi, who were associated with rituals involving dance and music.

738:

463:

376:

215:

80:

3460:Łakomska, Bogna (2020). "Images of Animals in Neolithic Chinese Ceramics".

3209:

The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age

3117:

2859:

Stephen D. Houston, The First Writing, ed. (2004). "7 (pp. 190–249)".

2794:

The Meaning of the Graph Yi 異 and Its Implications for Shang Belief and Art

1376:

oppress and tyrannize the people and bring villainy and treachery upon the

1373:

He blindly discards the sacrifices he should present and fails to respond .

1348:

904:

Zi Hua, entrusted to be a substitute conducting ale libation rituals ;

548:

There is only one inscription where a direct link between the king and the

3384:

3140:

2572:(2002), "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results",

2477:"Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang Dynasties"

1063:

545:

was not the person of choice to conduct all the sacrifices of appeasement;

2713:

1428:

1424:

1292:. According to the narrative, Wu Ding was carrying out a ritual honoring

1124:

1116:

1081:

227:

210:". According to this theory, since the religious reforms commissioned by

3088:

Schiffeler, John William (1976). "The Origin of Chinese Folk Medicine".

2723:

1255:, who was a chief minister of Tang, when he counsels the young new king

956:" could refer to an alternative place for performing an unknown ritual.

847:, should sacrifice (to) Ancestress Geng some pen-raised cattle. At Rong.

762:) were chosen to handle the task under the command of a music director (

145:(r. 1250 - 1192 BCE), who was the organizer of the burial of his father

3306:

3109:

3022:

The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Foundations of the Calendar

2832:

The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Foundations of the Calendar

2745:

Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China

1281:

1256:

1136:

1077:

1044:

858:

Other ancestral deities revered by the Huayuanzhuang entourage include

363:

291:

219:

142:

122:

3030:

2765:

2754:"The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Origins of the Calendar"

1377:

1331:

1330:

Shang excessive sacrifices were further criticized by a figure named

1252:

750:

715:

501:"a sacrifice, possibly linked to controlling the wind or meteorology"

483:

341:

231:

211:

171:

3243:

Chen, Kuang Yu; Song, Zhenhao; Liu, Yuan; Anderson, Matthew (2020),

3101:

1462:

An example is the Longshan culture, which practiced human sacrifice.

61:

Their activities, taking place at the Shang dynasty's capital city

3247:, Springer, Shanghai People's Publishing House, pp. 227–230,

1368:

1297:

1202:

1151:

1120:

1100:

1092:

cultures had utilized bony materials from cattles for divination.

1062:

742:

417:

112:

62:

25:

1139:

and allowed him to continue worshipping Shang spirits. The early

599:(he further claimed that "magician" is also a related term). In

1713:

Wang, Tao (2007). "Shang ritual animals: Colour and Meaning".

3445:"Contemporary Chinese Shamanism:The Reinvention of Tradition"

907:

Zi Pou and Zi Yu, who participated in sacrificial ceremonies;

2890:. Changchun: Dongbei Shifan Daxue Chubanshe. pp. 27–28.

2811:

Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot

1107:

dated to 9,000 years ago, and clay music instruments called

583:

by looking at linguistic evidence. According to his theory,

3301:(PhD thesis). University of British Columbia. p. 123.

2861:

Anyang Writing and the Origin of the Chinese Writing System

2546:, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 232–291,

1367:

Now for Shou, the king of Shang, it is indeed the words of

1259:

after Tang's own death. Yi Yin purportedly made a writing:

726: – 1180 BCE, one of which is the example of

218:

employed diviners and scribes of the type who worked under

2928:(1983). "Recent approaches to oracle-bone periodization".

2888:

Yinxu jiagu ziji yanjiu: Shizu buci pian (殷墟甲骨字跡研究— 師組卜辭篇)

2881:. Beijing: Shehui Kexue Wenxian Chubanshe. pp. 83–87.

2528:. Eds Ker, Martin & Dirk, Meyer. p. 298 of pp. 281-319

749:

on the sky. Wuxian was said to have served the Shang king

2678:

The Power of Culture: Studies in Chinese Cultural History

1316:

To rectify this affair, the king must first be corrected.

2676:(1994). "Shang Shamans". In Peterson, Willard J. (ed.).

1386:

King Wu of Zhou giving speech, translated by Martin Kern

627:

day Xi tested the proposition: As for meat cut with the

3373:

Metamorphic Imagery in Ancient Chinese Art and Religion

2680:. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. pp. 10–36.

2668:. Vol. 2, Xianqin (先秦). Beijing: Renmin chubanshe.

2252:

1936:

1934:

3126:

cannot be correctly translated in any way.</ref>

2951:

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies

1542:

1540:

1361:,昏棄厥遺王父母弟不迪。乃惟四方之多罪逋逃,是崇是長,是信是使,是以為大夫卿士,俾暴虐于百姓,以奸宄于商邑。

498:

of the north or east, to which sacrifices are offered"

2606:. Vol. I. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

2109:

2107:

2105:

1111:

thought to be 7,000 years old have been found in the

2614:

The Oracle Bone Inscriptions from Huayuanzhuang East

2518:"Chapter 8: The "Harangues" (Shi 誓) in the Shangshu"

1612:

1610:

1608:

1606:

2379:

The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States

1557:

1555:

1491:

438:

Using divinations written by diviner groups Huáng (

1527:

1525:

1523:

1521:

1519:

1506:

1504:

1502:

1500:

1337:The last Shang king, Di Xin, was described by the

1214:Chinese tradition describes the first Shang king,

1177:to memorialize his royal Shang ancestral spirits.

870:sacrifices to the spirits, as one text indicates:

2526:Studies in the History of Chinese Texts, Volume 8

1233:, and prayer made for rain. Tang allegedly said,

631:it should be the king who carries out invocation.

2597:(PhD thesis). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

1805:

1071:, where ancestor worship rituals were practiced.

3443:Zhang, Hong; Hriskos, Constantine (June 2003).

2497:James Legge (ed.). "The Announcement of Tang".

1861:

1859:

1597:

1353:

1306:

1290:"Day of the Supplementary Sacrifice to Gaozong"

1261:

987:

872:

809:

783:

682:

644:

620:

587:during the Shang dynasty had the pronunciation

2852:"Shang Period Government, Administration, Law"

2291:Social Scientific Studies of Religion in China

2228:

1901:

1889:

1877:

772:Practitioners not belonging to the royal court

478:The Shang dynasty had a court position called

2430:

1355:

1308:

1003:

994:

973:

964:

951:

941:

874:

831:

811:

785:

763:

757:

684:

669:

508:

445:

439:

117:Shang king Wu Ding, a highly religious ruler.

8:

3004:. Berkeley: University of California Press.

2264:

1235:"If a man must be the victim, I will be he."

3318:. Berkeley: University of California Press.

2366:. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. pp. 57–63.

1913:

1781:

1043:, and there is an oracle bone anticipating

2666:Zhongguo zhengzhi zhidu tongshi (中國政治制度通史)

2337:

1826:

1757:

1733:

1676:

1573:

3345:Education in Traditional China: A History

3139:

3132:Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory

2949:Boileau, Gilles (2002). "Wu and Shaman".

2722:

2712:

2408:. Cambridge University Press. p. 4.

1745:

3366:(in Chinese). Shanghai renmin chubanshe.

2863:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2240:

2060:

2048:

2036:

2024:

1964:

1940:

1925:

1546:

410:

382:

356:

317:

288:

285:

236:

181:

3179:(in Chinese), Beijing: Xianzhuang shuju

2462:"Ten plus two dukes" and related issues

1850:

1838:

1484:

1397:

1159:rebelled together with the Three Guards

3201:(MA thesis) (in Chinese). Furen daxue.

2544:The Cambridge History of Ancient China

2325:

2150:Song Zhenhao (宋鎮豪). Wang Yuxin (ed.).

2125:

2113:

2096:

2084:

1616:

753:, as both an astronomer and a shaman.

230:favored those of the type working for

3462:Athens Journal of Humanities and Arts

3134:, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton,

2289:Yang, Fenggang; Lang, Graeme (2012).

2166:

2137:

2072:

1793:

1652:

1561:

960:could possibly be a noun in HD: 181 (

513:, a form of divination using achilea"

256:

87:is under debate. Researchers such as

16:Ancient Chinese polytheistic religion

7:

3449:Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine

2978:Xu, Yahui (許雅惠 Hsu Ya-huei) (2002).

2664:Wang, Yuxin; Yang, Shengnan (1996).

2349:

2313:

2216:

1988:

1531:

1510:

969:‘to go to the xué’) and in HD: 450 (

3421:The Prehistory of Religion in China

2870:Writing and Literacy in Early China

2364:Zhongguo kaoguxue yanjiu bianweihui

2204:

2000:

1976:

1952:

1700:

1271:Yi Yin to Tai Jia, recorded in the

827:in Rong’s eastern guesthouse. Used.

520:The inscriptions about this living

3471:Liangzhu shenqi yu jitan (良渚神祗与祭坛)

3423:. Oxford University Press, p.443.

3403:A Companion to Chinese Archaeology

2982:. Taipei: National Palace Museum.

2792:Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth (2008).

2276:

2012:

1769:

1688:

1664:

1640:

1628:

1585:

579:, theorized a possible meaning of

14:

3170:(in Chinese), Taipei: Taiwan guji

2872:. University of Washington Press.

2695:Mizoguchi; Uchida (31 May 2018).

2574:Journal of East Asian Archaeology

937:The Shang character for "learn" (

823:: Should carry in offerings (to)

532:is a man or a woman is not known;

466:was an important practice to the

238:Classification of diviner groups

1865:

1027:Training other ritual activities

3265:, China Social Sciences Press,

3206:Li, Liu; Chen, Xingcan (2012).

3130:Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2019),

2156:(in Chinese). pp. 220–230.

1157:After King Wu's death, Wu Geng

678:Other court religious positions

3212:. Cambridge University Press.

2897:Cong jiaguwen kaoshu Shang dai

2760:. Oxbow Books. pp. 1–37.

2642:"History G380: Shang Religion"

2381:. Cambridge University Press.

1207:Tang of Shang, as depicted by

1197:Records of the Grand Historian

159:, a long-term opponent of the

1:

3497:Religion in the Shang dynasty

3469:Du, Jinpeng (February 1997).

3283:, Shanghai University Press,

3245:Reading of Shāng Inscriptions

3080:The Religious System of China

2654:"History G380: Shang Society"

2552:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.006

1598:Mizoguchi & Uchida (2018)

1349:"Book of Zhou - Speech at Mu"

1144:

1047:'s inspection of the dances.

843:, carrying in offerings (to)

720:

698:(day 57), the moon was eaten.

195:

194:Throughout the interval from

73:

50:

31:

21:Religion of the Shang dynasty

2756:. In Steele, John M. (ed.).

2443:(in Chinese), pp. 38–43

524:reveal six characteristics:

426:

413:

395:

385:

372:

359:

337:

320:

2752:Smith, Adam Daniel (2011).

2604:Yindai zhenbu renwu tongkao

1325:Zu Ji to his father Wu Ding

257:Major royal diviner groups

3513:

3482:. Current Anthropology 49.

3343:Lee, Thomas H. C. (2000).

3261:Hu, Houxuan, ed. (2009),

3236:Cambridge University Press

2611:Schwartz, Adam C. (2020).

2586:10.1163/156852302322454585

2486:. No. 108. p. 3.

2429:Shaanxi Zhouyuan Kaogudui

2265:Zhang & Hriskos (2003)

1251:also refers to a quote by

178:Participants of divination

18:

3405:, John Wiley & Sons,

3337:10.1017/S0362502800002078

3076:de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria

3060:10.1017/S036250280000451X

2963:10.1017/S0041977X02000149

2942:10.1017/S0362502800005411

2918:10.1017/S0362502800004442

2850:Theobald, Ulrich (2018).

2431:

2193:10.1017/S0362502800002078

1423:Dong also included kings

1356:

1309:

1004:

995:

974:

965:

952:

942:

922:Training of practitioners

875:

832:

812:

786:

764:

758:

685:

670:

509:

446:

440:

421:

407:

403:

367:

353:

348:

305:

302:

290:

269:

253:

247:

242:

3363:

3362:Yang Kuam (楊寬) (2003).

3280:

3279:Ma Rusen (馬如森) (2010),

3262:

3198:

3197:Gu Yu'an (古育安) (2009).

3189:

3185:

3176:

3175:Zhao Peng (趙鵬) (2007),

3167:

3166:Wei Cide (魏慈德) (2006),

2594:

2593:Sun Yabing 孫亞冰 (2014).

2456:

2440:

2436:

2402:Jin Jie (3 March 2011).

2152:

704:oracle bone Heji 40610v.

556:does not appear clearly;

3122:The author argued that

2886:Zhang, Shichao (2002).

2475:Chang, Ruth H. (2000).

2454:Zhang Zhenglang (张政烺),

1806:von Falkenhausen (1995)

1148: 11th century BCE

1131:During the Zhou dynasty

694:(day 56) cleaving into

665:The invocation ritual (

251:'s inscription periods

58:a polytheistic religion

56:- 1046 BCE), developed

3419:Nickel, Lukas (2011).

3314:Moore, Oliver (2000).

3090:Asian Folklore Studies

2926:Shaughnessy, Edward L.

2807:(192). Victor H. Mair.

1760:, pp. 97–98, 203.

1547:Wang & Yang (1996)

1389:

1328:

1278:

1211:

1072:

1054:History of development

1016:

897:

884:: In sacrificing (to)

856:

808:

701:

663:

643:

591:, related to the term

563:Some pointed out that

462:It is unknown whether

187:

118:

38:

3385:10.4324/9781003341246

3347:. Brill. p. 41.

3297:Liu, Xueshun (2005).

3141:10.1515/9781501516948

2659:. Indiana University.

2652:Eno, Robert (2010b).

2647:. Indiana University.

2640:Eno, Robert (2010a).

2602:Jao, Tsung-I (1959).

2229:Childs-Johnson (2023)

1902:Childs-Johnson (1995)

1890:Childs-Johnson (1995)

1878:Childs-Johnson (2008)

1206:

1184:Traditional narrative

1066:

876:乙卯卜:歲祖乙牢,子其自,弜(勿)速。用。

833:癸丑,將妣庚,其歲妣庚牢。在(戎)。一二三

647:At divination on the

623:At divination on the

454:liturgical schedule.

329:Lì 歷, type 2 (father

309:Lì 歷, type 1 (father

185:

116:

43:royal regime of China

29:

3019:Smith, Adam (2010).

2804:Sino-Platonic Papers

2714:10.15184/aqy.2018.19

2516:Kern, Martin (2017)

2484:Sino-Platonic Papers

2253:Nelson et al. (2006)

2085:Li & Chen (2012)

1736:, p. 32, n. 18.

1275:(trans. James Legge)

1059:Neolithic precursors

813:戊申卜:其將妣庚于(戎)東官(館)。用。

728:"the moon was eaten"

222:, while others like

163:, was assigned with

2998:Keightley, David N.

787:己亥卜:子于(戎)宿,夙殺牢妣庚。用。

690:On the seventh day

504:"an equivalent for

239:

65:, were recorded on

3307:10.14288/1.0099806

3184:Lin, Yun (2007),

2899:. pp. 224–25.

2623:20.500.12657/23217

2464:] (in Chinese)

2352:, p. 403-437.

2099:, p. 190-249.

1914:Shaughnessy (2019)

1841:, p. 354-355.

1808:, p. 279-300.

1784:, p. 9, n. 1.

1782:Shaughnessy (1983)

1492:Chen et al. (2020)

1224:and the historian

1212:

1073:

932:Oracle bone script

237:

188:

119:

39:

3478:Flad, R. (2008).

3412:978-1-4443-3529-3

3354:978-9-004-10363-4

3290:978-7-811-18651-2

3272:978-7-5004-8462-2

3254:978-981-15-6213-6

3232:The First Writing

3219:978-0-521-64310-8

3151:978-1-5015-1694-8

3042:Officials in the

2989:978-957-562-420-0

2775:978-1-84217-987-1

2741:Chang, Kwang-Chih

2687:978-962-201-596-8

2674:Chang, Kwang-Chih

2561:978-0-521-47030-8

2500:Book of Documents

2415:978-0-521-18691-9

2388:978-0-521-81184-2

2338:Keightley (1978a)

2300:978-9-004-18246-2

1827:Schiffeler (1976)

1758:Keightley (1978a)

1734:Keightley (1978a)

1677:Keightley (1978a)

1574:Keightley (1978a)

1371:that he follows.

1344:Book of Documents

1286:Book of Documents

1273:Book of Documents

1248:Book of Documents

575:civilization and

436:

435:

3504:

3483:

3474:

3465:

3456:

3439:

3434:

3415:

3397:

3367:

3358:

3339:

3319:

3310:

3293:

3275:

3257:

3239:

3223:

3202:

3199:殷墟花東H3甲骨刻辭所見人物研究

3193:

3180:

3171:

3162:

3143:

3121:

3083:

3071:

3034:

3031:10.7916/D8891CDX

3015:

2993:

2974:

2945:

2921:

2900:

2891:

2882:

2873:

2864:

2855:

2846:

2808:

2797:

2788:

2779:

2766:10.7916/D8891CDX

2748:

2736:

2726:

2716:

2707:(363): 709–723.

2691:

2669:

2660:

2658:

2648:

2646:

2636:

2607:

2598:

2589:

2565:

2529:

2514:

2508:

2507:

2505:

2494:

2488:

2487:

2481:

2472:

2466:

2465:

2451:

2445:

2444:

2434:

2433:

2426:

2420:

2419:

2399:

2393:

2392:

2377:Liu, Li (2005).

2374:

2368:

2367:

2359:

2353:

2347:

2341:

2335:

2329:

2323:

2317:

2311:

2305:

2304:

2286:

2280:

2279:, p. 52-62.

2274:

2268:

2262:

2256:

2250:

2244:

2238:

2232:

2226:

2220:

2214:

2208:

2202:

2196:

2195:

2176:

2170:

2164:

2158:

2157:

2147:

2141:

2135:

2129:

2123:

2117:

2111:

2100:

2094:

2088:

2082:

2076:

2070:

2064:

2058:

2052:

2046:

2040:

2034:

2028:

2022:

2016:

2010:

2004:

1998:

1992:

1986:

1980:

1974:

1968:

1962:

1956:

1955:, p. 20-21.

1950:

1944:

1938:

1929:

1923:

1917:

1911:

1905:

1899:

1893:

1887:

1881:

1875:

1869:

1863:

1854:

1848:

1842:

1836:

1830:

1829:, p. 17-35.

1824:

1818:

1817:de Groot (1964)

1815:

1809:

1803:

1797:

1791:

1785:

1779:

1773:

1767:

1761:

1755:

1749:

1746:Keightley (1999)

1743:

1737:

1731:

1725:

1724:

1716:Bulletin of SOAS

1710:

1704:

1698:

1692:

1686:

1680:

1679:, p. 13-14.

1674:

1668:

1662:

1656:

1650:

1644:

1638:

1632:

1626:

1620:

1614:

1601:

1595:

1589:

1583:

1577:

1571:

1565:

1559:

1550:

1544:

1535:

1529:

1514:

1508:

1495:

1489:

1472:

1469:

1463:

1460:

1454:

1451:

1445:

1442:

1436:

1421:

1415:

1411:

1405:

1402:

1387:

1363:

1362:

1326:

1312:

1311:

1276:

1149:

1146:

1069:Longshan culture

1014:

1007:

1006:

998:

997:

977:

976:

968:

967:

955:

954:

945:

944:

927:Scribal training

895:

878:

877:

854:

835:

834:

815:

814:

806:

789:

788:

779:Grandmother Gēng

767:

766:

761:

760:

741:, stated in the

725:

722:

705:

688:

687:

673:

672:

661:

641:

607:(plural form of

512:

511:

473:Kwang-chih Chang

449:

448:

443:

442:

240:

200:

197:

78:

75:

55:

52:

36:

33:

3512:

3511:

3507:

3506:

3505:

3503:

3502:

3501:

3487:

3486:

3477:

3468:

3459:

3442:

3437:

3431:

3418:

3413:

3400:

3395:

3370:

3365:

3361:

3355:

3342:

3322:

3313:

3296:

3291:

3282:

3278:

3273:

3264:

3260:

3255:

3242:

3226:

3220:

3205:

3200:

3196:

3191:

3187:

3183:

3178:

3177:殷墟甲骨文人名與斷代的初步研究

3174:

3169:

3165:

3152:

3129:

3102:10.2307/1177648

3087:

3074:

3037:

3018:

3012:

2996:

2990:

2977:

2948:

2924:

2903:

2895:Song, Zhenhao.

2894:

2885:

2876:

2867:

2858:

2849:

2843:

2828:

2800:

2791:

2782:

2776:

2751:

2739:

2694:

2688:

2672:

2663:

2656:

2651:

2644:

2639:

2633:

2610:

2601:

2596:

2592:

2568:

2562:

2541:

2538:

2533:

2532:

2515:

2511:

2503:

2496:

2495:

2491:

2479:

2474:

2473:

2469:

2458:

2453:

2452:

2448:

2442:

2438:

2428:

2427:

2423:

2416:

2401:

2400:

2396:

2389:

2376:

2375:

2371:

2361:

2360:

2356:

2348:

2344:

2336:

2332:

2324:

2320:

2312:

2308:

2301:

2288:

2287:

2283:

2275:

2271:

2263:

2259:

2251:

2247:

2243:, p. 1-17.

2241:Łakomska (2020)

2239:

2235:

2227:

2223:

2215:

2211:

2203:

2199:

2178:

2177:

2173:

2165:

2161:

2154:

2149:

2148:

2144:

2136:

2132:

2124:

2120:

2112:

2103:

2095:

2091:

2083:

2079:

2071:

2067:

2061:Schwartz (2020)

2059:

2055:

2049:Schwartz (2020)

2047:

2043:

2037:Schwartz (2020)

2035:

2031:

2025:Schwartz (2020)

2023:

2019:

2011:

2007:

1999:

1995:

1987:

1983:

1975:

1971:

1965:Schwartz (2020)

1963:

1959:

1951:

1947:

1941:Schwartz (2020)

1939:

1932:

1926:Theobald (2018)

1924:

1920:

1912:

1908:

1900:

1896:

1888:

1884:

1876:

1872:

1864:

1857:

1849:

1845:

1837:

1833:

1825:

1821:

1816:

1812:

1804:

1800:

1792:

1788:

1780:

1776:

1768:

1764:

1756:

1752:

1744:

1740:

1732:

1728:

1712:

1711:

1707:

1699:

1695:

1687:

1683:

1675:

1671:

1663:

1659:

1651:

1647:

1639:

1635:

1627:

1623:

1615:

1604:

1596:

1592:

1584:

1580:

1572:

1568:

1560:

1553:

1545:

1538:

1530:

1517:

1509:

1498:

1490:

1486:

1481:

1476:

1475:

1470:

1466:

1461:

1457:

1452:

1448:

1443:

1439:

1422:

1418:

1412:

1408:

1403:

1399:

1394:

1388:

1385:

1327:

1324:

1277:

1270:

1186:

1147:

1133:

1061:

1056:

1029:

1015:

1012:

929:

924:

896:

893:

855:

852:

845:Ancestress Gēng

825:Ancestress Gēng

807:

804:

797:Ancestress Gēng

774:

723:

707:

703:

680:

662:

656:

642:

636:

490:is identified:

460:

244:

198:

180:

111:

102:David Keightley

98:

77: 1250 BCE

76:

53:

34:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

3510:

3508:

3500:

3499:

3489:

3488:

3485:

3484:

3475:

3466:

3457:

3440:

3435:

3429:

3416:

3411:

3398:

3393:

3368:

3359:

3353:

3340:

3320:

3311:

3294:

3289:

3276:

3271:

3258:

3253:

3240:

3228:Bagley, Robert

3224:

3218:

3203:

3194:

3181:

3172:

3163:

3150:

3127:

3085:

3072:

3035:

3016:

3010:

2994:

2988:

2975:

2957:(2): 350–378.

2946:

2922:

2901:

2892:

2883:

2874:

2865:

2856:

2847:

2841:

2826:

2798:

2789:

2783:Mair, Victor.

2780:

2774:

2749:

2737:

2692:

2686:

2670:

2661:

2649:

2637:

2631:

2617:. De Gruyter.

2608:

2599:

2590:

2566:

2560:

2537:

2534:

2531:

2530:

2509:

2489:

2467:

2446:

2437:陝西岐山鳳雛村發現周初甲骨文

2421:

2414:

2394:

2387:

2369:

2354:

2342:

2330:

2328:, p. 443.

2318:

2316:, p. 250.

2306:

2299:

2281:

2269:

2257:

2245:

2233:

2221:

2219:, p. 664.

2209:

2197:

2171:

2159:

2142:

2130:

2118:

2101:

2089:

2077:

2065:

2053:

2041:

2029:

2017:

2005:

1993:

1981:

1969:

1957:

1945:

1930:

1918:

1906:

1894:

1882:

1870:

1855:

1853:, p. 355.

1843:

1839:Boileau (2002)

1831:

1819:

1810:

1798:

1786:

1774:

1772:, p. 330.

1762:

1750:

1748:, p. 241.

1738:

1726:

1705:

1693:

1681:

1669:

1657:

1645:

1633:

1621:

1602:

1590:

1578:

1576:, p. 1-2.

1566:

1551:

1536:

1515:

1496:

1483:

1482:

1480:

1477:

1474:

1473:

1464:

1455:

1446:

1437:

1416:

1406:

1396:

1395:

1393:

1390:

1383:

1322:

1268:

1185:

1182:

1165:, as ruler of

1132:

1129:

1060:

1057:

1055:

1052:

1028:

1025:

1010:

928:

925:

923:

920:

912:

911:

908:

905:

891:

850:

802:

773:

770:

681:

679:

676:

654:

634:

601:Zoroastrianism

561:

560:

557:

546:

539:

536:

533:

518:

517:

514:

502:

499:

459:

456:

434:

433:

428:

424:

423:

420:

415:

412:

409:

405:

404:

402:

397:

393:

392:

387:

384:

380:

379:

374:

370:

369:

366:

361:

358:

355:

351:

350:

347:

344:

339:

335:

334:

327:

322:

319:

315:

314:

307:

304:

300:

299:

297:

294:

289:

287:

283:

282:

279:

277:

275:

273:

271:

267:

266:

263:

259:

258:

255:

254:Kings' reigns

252:

246:

245:pottery layer

179:

176:

110:

107:

97:

94:

85:Shang religion

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

3509:

3498:

3495:

3494:

3492:

3481:

3476:

3472:

3467:

3463:

3458:

3454:

3450:

3446:

3441:

3436:

3432:

3430:9780199232444

3426:

3422:

3417:

3414:

3408:

3404:

3399:

3396:

3394:9781003341246

3390:

3386:

3382:

3378:

3374:

3369:

3360:

3356:

3350:

3346:

3341:

3338:

3334:

3330:

3326:

3321:

3317:

3312:

3308:

3304:

3300:

3295:

3292:

3286:

3277:

3274:

3268:

3259:

3256:

3250:

3246:

3241:

3237:

3234:. Cambridge:

3233:

3229:

3225:

3221:

3215:

3211:

3210:

3204:

3195:

3182:

3173:

3168:殷墟花園莊東地甲骨卜辭研究

3164:

3161:

3157:

3153:

3147:

3142:

3137:

3133:

3128:

3125:

3119:

3115:

3111:

3107:

3103:

3099:

3095:

3091:

3086:

3081:

3077:

3073:

3069:

3065:

3061:

3057:

3053:

3049:

3045:

3041:

3036:

3032:

3028:

3024:

3023:

3017:

3013:

3011:0-520-02969-0

3007:

3003:

2999:

2995:

2991:

2985:

2981:

2976:

2972:

2968:

2964:

2960:

2956:

2952:

2947:

2943:

2939:

2935:

2931:

2927:

2923:

2919:

2915:

2912:(20): 79–92.

2911:

2907:

2902:

2898:

2893:

2889:

2884:

2880:

2875:

2871:

2866:

2862:

2857:

2853:

2848:

2844:

2842:9783945561355

2838:

2834:

2833:

2827:

2825:

2824:

2819:

2818:

2813:

2812:

2806:

2805:

2799:

2795:

2790:

2786:

2781:

2777:

2771:

2767:

2763:

2759:

2755:

2750:

2746:

2742:

2738:

2734:

2730:

2725:

2720:

2715:

2710:

2706:

2702:

2698:

2693:

2689:

2683:

2679:

2675:

2671:

2667:

2662:

2655:

2650:

2643:

2638:

2634:

2632:9781501505331

2628:

2624:

2620:

2616:

2615:

2609:

2605:

2600:

2595:殷墟花園莊東地甲骨文例研究

2591:

2587:

2583:

2579:

2575:

2571:

2567:

2563:

2557:

2553:

2549:

2545:

2540:

2539:

2535:

2527:

2523:

2519:

2513:

2510:

2506:. p. 51.

2502:

2501:

2493:

2490:

2485:

2478:

2471:

2468:

2463:

2459:

2450:

2447:

2425:

2422:

2417:

2411:

2407:

2406:

2405:Chinese Music

2398:

2395:

2390:

2384:

2380:

2373:

2370:

2365:

2358:

2355:

2351:

2346:

2343:

2339:

2334:

2331:

2327:

2326:Nickel (2011)

2322:

2319:

2315:

2310:

2307:

2302:

2296:

2292:

2285:

2282:

2278:

2273:

2270:

2266:

2261:

2258:

2254:

2249:

2246:

2242:

2237:

2234:

2230:

2225:

2222:

2218:

2213:

2210:

2207:, p. 41.

2206:

2201:

2198:

2194:

2190:

2186:

2182:

2175:

2172:

2169:, p. 25.

2168:

2163:

2160:

2155:

2153:從⭢骨文考述商代的學校教育

2146:

2143:

2139:

2134:

2131:

2127:

2126:Michio (2003)

2122:

2119:

2115:

2114:Smith (2011a)

2110:

2108:

2106:

2102:

2098:

2097:Bagley (2004)

2093:

2090:

2086:

2081:

2078:

2074:

2069:

2066:

2063:, p. 64.

2062:

2057:

2054:

2051:, p. 51.

2050:

2045:

2042:

2039:, p. 47.

2038:

2033:

2030:

2027:, p. 46.

2026:

2021:

2018:

2014:

2009:

2006:

2002:

1997:

1994:

1990:

1985:

1982:

1978:

1973:

1970:

1967:, p. 44.

1966:

1961:

1958:

1954:

1949:

1946:

1942:

1937:

1935:

1931:

1927:

1922:

1919:

1916:, p. 85.

1915:

1910:

1907:

1903:

1898:

1895:

1892:, p. 87.

1891:

1886:

1883:

1879:

1874:

1871:

1867:

1862:

1860:

1856:

1852:

1847:

1844:

1840:

1835:

1832:

1828:

1823:

1820:

1814:

1811:

1807:

1802:

1799:

1795:

1790:

1787:

1783:

1778:

1775:

1771:

1766:

1763:

1759:

1754:

1751:

1747:

1742:

1739:

1735:

1730:

1727:

1722:

1718:

1717:

1709:

1706:

1702:

1697:

1694:

1691:, p. 28.

1690:

1685:

1682:

1678:

1673:

1670:

1667:, p. 24.

1666:

1661:

1658:

1654:

1649:

1646:

1642:

1637:

1634:

1630:

1625:

1622:

1618:

1617:Didier (2009)

1613:

1611:

1609:

1607:

1603:

1599:

1594:

1591:

1588:, p. 30.

1587:

1582:

1579:

1575:

1570:

1567:

1563:

1558:

1556:

1552:

1548:

1543:

1541:

1537:

1533:

1528:

1526:

1524:

1522:

1520:

1516:

1512:

1507:

1505:

1503:

1501:

1497:

1493:

1488:

1485:

1478:

1468:

1465:

1459:

1456:

1450:

1447:

1441:

1438:

1434:

1430:

1426:

1420:

1417:

1410:

1407:

1401:

1398:

1391:

1382:

1381:

1379:

1378:City of Shang

1374:

1370:

1364:

1360:

1352:

1350:

1346:

1345:

1340:

1335:

1333:

1321:

1320:

1315:

1305:

1303:

1299:

1295:

1291:

1287:

1283:

1274:

1267:

1266:

1260:

1258:

1254:

1250:

1249:

1243:

1241:

1236:

1232:

1227:

1223:

1219:

1218:

1210:

1205:

1201:

1199:

1198:

1193:

1192:

1183:

1181:

1178:

1176:

1172:

1168:

1164:

1160:

1155:

1153:

1142:

1138:

1130:

1128:

1126:

1122:

1118:

1114:

1110:

1106:

1102:

1098:

1097:Wuyang County

1093:

1091:

1087:

1083:

1079:

1070:

1065:

1058:

1053:

1051:

1048:

1046:

1042:

1038:

1034:

1026:

1024:

1020:

1009:

1002:

993:

986:

984:

979:

972:

963:

959:

949:

940:

935:

933:

926:

921:

919:

915:

909:

906:

903:

902:

901:

890:

889:

885:

881:

871:

867:

865:

861:

849:

848:

844:

840:

836:

829:

828:

824:

820:

816:

801:

800:

796:

792:

782:

780:

771:

769:

754:

752:

748:

744:

740:

736:

731:

730:on the left.

729:

717:

713:

706:

700:

699:

695:

691:

677:

675:

668:

659:

653:

652:

648:

639:

633:

632:

628:

624:

619:

616:

612:

610:

606:

602:

598:

594:

590:

586:

582:

578:

574:

570:

569:Shang dynasty

566:

558:

555:

551:

547:

544:

540:

537:

534:

531:

527:

526:

525:

523:

515:

507:

503:

500:

497:

493:

492:

491:

489:

485:

481:

476:

474:

469:

468:Shang dynasty

465:

457:

455:

453:

432:

429:

425:

419:

416:

406:

401:

398:

394:

391:

388:

381:

378:

375:

371:

365:

362:

352:

345:

343:

340:

336:

332:

328:

326:

323:

316:

312:

308:

301:

298:

296:Shī 師/Duī 𠂤

295:

293:

284:

280:

278:

276:

274:

272:

268:

264:

261:

260:

250:

241:

235:

233:

229:

225:

221:

217:

213:

209:

205:

192:

184:

177:

175:

173:

168:

166:

162:

161:Shang dynasty

158:

152:

150:

149:

144:

139:

137:

133:

130:, written on

129:

124:

115:

109:Chief priests

108:

106:

103:

96:Practitioners

95:

93:

90:

86:

82:

70:

68:

64:

59:

48:

47:Shang dynasty

44:

28:

22:

3479:

3470:

3461:

3452:

3448:

3420:

3402:

3372:

3344:

3328:

3324:

3315:

3298:

3244:

3231:

3208:

3192:(in Chinese)

3131:

3123:

3096:(1): 17–35.

3093:

3089:

3079:

3051:

3047:

3043:

3039:

3021:

3001:

2979:

2954:

2950:

2933:

2929:

2909:

2905:

2896:

2887:

2878:

2869:

2860:

2831:

2821:

2815:

2809:

2802:

2793:

2784:

2757:

2744:

2724:2324/2244064

2704:

2700:

2677:

2665:

2613:

2603:

2577:

2573:

2543:

2525:

2521:

2512:

2499:

2492:

2483:

2470:

2461:

2457:"十又二公"及其相关问题

2449:

2424:

2404:

2397:

2378:

2372:

2363:

2357:

2345:

2333:

2321:

2309:

2290:

2284:

2272:

2260:

2248:

2236:

2224:

2212:

2200:

2184:

2180:

2174:

2167:Moore (2000)

2162:

2145:

2138:Zhang (2002)

2133:

2121:

2092:

2080:

2073:Smith (2019)

2068:

2056:

2044:

2032:

2020:

2008:

1996:

1984:

1972:

1960:

1948:

1921:

1909:

1897:

1885:

1873:

1851:Boileau 2002

1846:

1834:

1822:

1813:

1801:

1794:Smith (2010)

1789:

1777:

1765:

1753:

1741:

1729:

1720:

1714:

1708:

1696:

1684:

1672:

1660:

1653:Chang (1994)

1648:

1636:

1624:

1593:

1581:

1569:

1562:Chang (1983)

1487:

1467:

1458:

1449:

1440:

1419:

1409:

1400:

1372:

1366:

1365:

1358:

1354:

1342:

1339:Zhou dynasty

1336:

1329:

1317:

1313:

1307:

1301:

1289:

1285:

1279:

1272:

1263:

1262:

1246:

1244:

1239:

1234:

1230:

1215:

1213:

1195:

1189:

1187:

1179:

1175:Shu Yi Zhong

1174:

1156:

1141:Western Zhou

1134:

1113:Hemudu sites

1094:

1074:

1049:

1040:

1036:

1032:

1030:

1021:

1017:

1000:

991:

988:

980:

970:

961:

957:

947:

938:

936:

930:

916:

913:

898:

887:

883:

879:

873:

868:

864:Ancestor Jiă

863:

859:

857:

846:

842:

838:

837:

830:

826:

822:

818:

817:

810:

798:

794:

790:

784:

778:

775:

755:

746:

732:

727:

708:

702:

697:

693:

689:

683:

666:

664:

657:

650:

646:

645:

637:

630:

626:

622:

621:

617:

613:

608:

604:

592:

588:

584:

580:

564:

562:

553:

549:

542:

529:

528:Whether the

521:

519:

505:

495:

487:

479:

477:

461:

437:

330:

310:

207:

203:

193:

189:

169:

164:

156:

153:

146:

140:

135:

132:oracle bones

120:

99:

71:

67:oracle bones

40:

3325:Early China

3186:花東子卜辭所見人物研究

3048:Early China

2930:Early China

2906:Early China

2580:: 321–333,

2350:Flad (2008)

2314:Zhao (2013)

2217:Yang (2003)

2181:Early China

1989:Zhao (2007)

1532:Eno (2010b)

1511:Eno (2010a)

1105:bone flutes

1035:comes with

886:Ancestor Yǐ

880:Divined on

860:Ancestor Yǐ

819:Divined on

791:Divined on

735:Han dynasty

724: 1200

597:Old Persian

567:during the

494:"a spirit,

444:) and Chū (

400:Wén Wǔ Dīng

265:Subdivided

249:Dong Zuobin

243:Anyang team

206:" and the "

199: 1250

89:K. C. Chang

54: 1600

41:The second

35: 1250

3375:, London:

2570:Li, Xueqin

2524:. Series:

2205:Lee (2000)

2001:Lin (2007)

1977:Wei (2006)

1953:Sun (2014)

1701:Jao (1959)

1479:References

1357:今商王受惟婦言是用。

1265:reverence.

712:North Pole

686:七日己未斲庚申月又食

577:Inner Asia

452:Late Shang

354:Yinxu III

208:New School

204:Old School

128:divination

3377:Routledge

3160:243176989

3078:(1964) .

3068:247325956

3000:(1978a).

2733:165873637

2701:Antiquity

2435:(1979),

2293:. Brill.

2277:Du (1997)

2013:Gu (2009)

1770:Li (2002)

1689:Xu (2002)

1665:Xu (2002)

1641:Ma (2010)

1629:Hu (2009)

1586:Xu (2002)

1226:Sima Qian

1090:Neolithic

1086:shamanism

1013:Guo Moruo

983:Guo Moruo

739:Sima Qian

464:shamanism

408:Yinxu IV

377:Gēng Dīng

349:nameless

303:Yinxu II

262:Original

216:Geng Ding

3491:Category

3473:. Kaogu.

3118:11614235

2971:27656590

2936:: 1–13.

2743:(1983).

1429:Xiao Xin

1425:Pan Geng

1384:—

1369:his wife

1351:quotes:

1347:section

1323:—

1288:chpater

1269:—

1143:period (

1117:Zhejiang

1082:totemism

1011:—

892:—

851:—

803:—

696:gēngshēn

655:—

649:gēngchén

635:—

422:Huáng 黄

270:Yinxu I

228:Wen Ding

3316:Chinese

3263:甲骨文合集释文

3190:古文字與古代史

3110:1177648

3044:Zhou Li

2536:Sources

2432:陝西周原考古隊

1433:Xiao Yi

1359:昏棄厥肆祀弗答

1282:Wu Ding

1257:Tai Jia

1240:Shàngdì

1137:Wu Geng

1078:animism

1045:Wu Ding

962:wǎngxué

918:lords.

894:HYZ 294

853:HYZ 248

841:guǐchǒu

805:HYZ 267

799:. Used.

747:Shàngdì

573:Chinese

458:Shamans

364:Lǐn Xīn

325:Zǔ Gēng

292:Wǔ Dīng

281:

220:Wu Ding

148:Xiǎo Yǐ

143:Wu Ding

123:deities

83:in the

81:shamans

3427:

3409:

3391:

3351:

3287:

3281:甲骨金文拓本

3269:

3251:

3216:

3158:

3148:

3116:

3108:

3066:

3008:

2986:

2969:

2839:

2772:

2731:

2684:

2629:

2558:

2412:

2385:

2297:

1332:Fu Yue

1253:Yi Yin

1231:Heaven

1209:Ma Lin

1194:, the

1103:found

992:fànbĕn

821:wùshēn

751:Tai Wu

716:Thuban

658:Jinbun

638:Fu yin

625:gēngzǐ

484:shaman

431:Dì Xīn

346:Chū 出

342:Zǔ Jiǎ

306:Bīn 賓

232:Zu Jia

212:Zu Jia

172:Fu Hao

157:Tǔfāng

72:Since

45:, the

3156:S2CID

3106:JSTOR

3064:S2CID

2967:S2CID

2729:S2CID

2657:(PDF)

2645:(PDF)

2504:(PDF)

2480:(PDF)

2460:[

1392:Notes

1298:Zu Ji

1222:Xunzi

1191:Xunzi

1163:Weizi

1152:Di Yi

1125:Xi'an

1121:Banpo

1101:Henan

1041:shāng

1037:shāng

1001:xuékè

971:rùxué

882:yǐmăo

793:jǐhài

743:Shiji

692:jǐwèi

609:maguš

593:maguš

418:Dì Yǐ

390:Wǔ Yǐ

373:IIIb

368:Hé 何

360:IIIa

224:Wu Yi

3464:(7).

3455:(2).

3425:ISBN

3407:ISBN

3389:ISBN

3349:ISBN

3285:ISBN

3267:ISBN

3249:ISBN

3214:ISBN

3146:ISBN

3114:PMID

3006:ISBN

2984:ISBN

2837:ISBN

2770:ISBN

2682:ISBN

2627:ISBN

2556:ISBN

2410:ISBN

2383:ISBN

2295:ISBN

1866:Mair

1723:(2).

1431:and

1302:Book

1294:Tang

1245:The

1217:Tang

1167:Song

1119:and

1084:and

1067:The

660:3014

605:magi

589:*mag

396:IVb

386:IVa

357:III

338:IIb

331:Dīng

321:IIa

226:and

121:The

37:BCE)

3381:doi

3364:西周史

3333:doi