50:

609:. Descartes had made the thinking subject the foundation of objective certainty in his famous statement, "I think, therefore I am". It was on this system that he based the possibility of knowing and understanding the world. In allowing that the passions could disrupt the process of reasoning within a human, he allowed for an inherent flaw in this proof – and if man was forced to doubt the truth of his own perceptions, on what could he base his understanding of the natural world?

369:

575:

482:, Descartes defines the passions as "the perceptions, sensations, or commotions of the soul which we relate particularly to the soul and are caused, maintained, and strengthened by some movement of the spirits" (art. 27). The "spirits" mentioned in this definition are "animal spirits", a notion central to understanding Descartes' physiology. These spirits function in a capacity similar to modern medicine's

719:'s, while Descartes' remains more closely tied to Aristotle. The confusion which ties Ryle so closely to Descartes arises from a confusing mix of metaphors; Descartes and his contemporaries conceptualized of the mind as a thing of physical (if inconceivable) proportions, which allowed for a differentiation between "inner" and "outer" sense. This ties back to Descartes'

514:

But there aren't many simple and basic passions... you'll easily see that there are only six: wonder, love, hatred, desire, joy, sadness. All the others are either composed from some of these six or they are species of them. So I'll help you to find your way through the great multitude of passions by

493:

Descartes does not reject the passions in principle; instead, he underlines their beneficial role in human existence. He maintains that humans should work to better understand their function in order to control them rather than be controlled by them. Thus, "ven those who have the weakest souls could

402:

asserts that the examination of the passions present in

Descartes' work plays a significant role in illustrating the development of the perception of the cognitive mind in western society. According to her article "From Passions to Emotions and Sentiments", Descartes' need to reconcile the influence

442:

In the context of the mechanistic view of life which was gaining popularity in seventeenth century science, Descartes perceived the body as an autonomous machine, capable of moving independently of the soul. It was from this physiological perception of the body that

Descartes developed his theories

656:

At the same time, Descartes' modernity must also be appreciated. Even while outlining the passions and their effect, he never issues an overarching interdiction against them as fatal human defects to be avoided at all costs. He recognizes them as an inherent aspect of humanity, not to be taken as

643:

The passions that

Descartes studies are in reality the actions of the body on the soul (art. 25). The soul suffers the influence of the body and is entirely subject to the influence of the passions. In the manner by which Descartes explains the human body, the animal spirits stimulate the pineal

652:

The passions attack the soul and force the body to commit inappropriate actions. It was therefore necessary for

Descartes to study in the second part of his treatise the particular effects of each separate passion and its manners of manifestation. The study of the passions permits one to better

474:

The passions such as

Descartes understood them correspond roughly to the sentiments now called emotions, but there exist several important distinctions between the two. The principle of these is that passions, as is suggested by the word’s etymology, are by nature suffered and endured, and are

682:

understanding of reality, however, he indicated that it is necessary to know the passions, and learn to control them in order to put them to the best possible use. It is also necessary, therefore, that a man strive to master the separation which exists between the corporeal body and the mind.

681:

For

Descartes, nothing could be more damaging to the soul and therefore the thought-process, which is its primary function (art. 17), than the body (art. 2). He maintained that the passions are not harmful in and of themselves. To protect the independence of the thoughts and guarantee a man’s

486:. Descartes explains that these animal spirits are produced in the blood and are responsible for the physical stimulation which causes the body to move. In affecting the muscles, for example, the animal spirits "move the body in all the different ways it is capable of" (

438:

traditions which defined the passions as the illnesses of the soul and which dictate that they be treated as such. Descartes thus affirmed that the passions "are all intrinsically good, and that all we have to avoid is their misuse or their excess" (art. 211).

620:. While Descartes argues against the existence of a final cause in physics, the nature of his work on examining the origins and functions of desires in the human soul necessitates the existence of a final goal towards which the individual is working.

657:

aberrations. Furthermore, the role of the passions on the body is not insignificant. Descartes indicates that they must be harnessed in order to learn which are good and bad for the body, and therefore for the individual (art. 211 and 212).

595:

is one of the most important of

Descartes' published works. Descartes wrote the treatise in response to an acute philosophical anxiety, and yet in doing so, he risked destroying the entirety of his previous work and the

426:. "My design is not to explain the passions as an Orator", he wrote in a letter to his editor dated August 14, 1649, "nor even as a Philosopher, but only as a Physicist." In doing so, Descartes broke not only from the

660:

Thus the majority of the work is devoted to enumerating the passions and their effects. He begins with the six basic passions and then touches on the specific passions which stem from their combination. For example,

475:

therefore the result of an external cause acting upon a subject. In contrast, modern psychology considers emotions to be a sensation which occurs inside a subject and therefore is produced by the subject themselves.

549:) that Descartes begins his investigation on their physiological effects and their influence on human behavior. He then follows by combining the six passions to create a holistic picture of the passions.

49:

603:

The problem arises from the fact that the passions, inextricably based in human nature, threaten the supremacy of the thinking subject on which

Descartes based his philosophical system, notably in

411:

In the context of the development of scientific thought in the seventeenth century which was abandoning the idea of the cosmos in favor of an open universe guided by inviolable laws of nature (see

510:

to moral philosophy, Descartes represented the problem of the passions of the soul in terms of its simplest integral components. He distinguishes between six fundamentally distinct passions:

422:

It was in this context that

Descartes wished to speak of the passions, neither as a moralist nor from a psychological perspective, but as a method of exploring a fundamental aspect of

715:", completely separating the physical body and from the metaphysical "mind" which actually encapsulates the spirit as well. Alanen argues that this philosophy is more akin to that of

636:. In the first part of his work, Descartes ponders the relationship between the thinking substance and the body. For Descartes, the only link between these two substances is the

403:

of the passions on otherwise rational beings marks a clear point in the advancement of human self-estimation, paralleling the increasingly rational-based scientific method.

451:

The treatise is based on the philosophy developed by

Descartes in his previous works, especially the distinction between the body and the soul: the soul thinks (

443:

on the passions of the soul. Formerly considered to be an anomaly, the passions became a natural phenomenon, necessitating a scientific explanation.

193:

960:

289:

188:

566:

The work is further divided, within the three greater parts, into 212 short articles which rarely exceed a few paragraphs in length.

669:

are two of the passions derived from the basic passion of admiration (art. 150). The passion which Descartes valued the most is

213:

612:

Additionally, a further distinction between Descartes' writings on physics and those on human nature such as can be found in

460:

377:

317:

126:

494:

acquire absolute mastery over all their passions if they worked hard enough at training and guiding them" (art. 50).

141:

241:

33:

653:

understand and account for these elements which may otherwise disturb a human's rational reasoning capabilities.

256:

111:

760:

218:

415:), human actions no longer depended on understanding the order and mechanism of the universe (as had been the

743:

605:

507:

282:

203:

79:

749:

116:

732:

325:

198:

723:, which derived knowledge and understanding of external realities on the basis of internal certainty.

707:(1949), is commonly associated with a modern-day application of Descartes' philosophy as put forth in

574:

712:

955:

703:

246:

136:

754:

459:) but does not think and is primarily defined by its form and movement. This is what is known as

348:

344:

275:

261:

106:

929:

412:

336:

period – that had been a subject of debate among philosophers and theologians since the time of

208:

737:

633:

468:

385:

321:

151:

121:

41:

430:

tradition (according to which the movements of the body originate in the soul), but also the

965:

526:

416:

162:

131:

95:

515:

treating the six basic ones separately, and then showing how all the others stem from them.

368:

343:

Notable precursors to Descartes who articulated their own theories of the passions include

427:

423:

309:

146:

84:

74:

399:

17:

483:

251:

89:

949:

352:

876:

860:

844:

815:

698:

694:

637:

597:

435:

156:

64:

693:

In her examination of the popular modern misconceptions of Descartes' philosophy,

798:

666:

559:

The Number and Order of the Passions and explanations of the six basic passions;

169:

69:

333:

101:

324:

contributes to a long tradition of philosophical inquiry into the nature of "

793:

617:

381:

900:

Robert Rethy, "The Teaching of Nature and the Nature of Man in Descartes'

670:

662:

431:

546:

329:

538:

389:

380:, in which he answered her moral questions, especially the nature of

779:

Amélie Oksenberg Rorty, "From Passions to Emotions and Sentiments",

891:, René Descartes LGF, coll. « Poche », Paris, 1990, p. 5.

937:

716:

573:

419:), but instead on understanding the essential workings of nature.

367:

337:

556:

The Passions in General and incidentally the whole nature of man;

913:

Lilli Alanen, "Descartes's dualism and the philosophy of mind",

644:

gland and cause many troubles (or strong emotions) in the soul.

534:

530:

376:

In 1643 Descartes began a prolific written correspondence with

542:

506:

is indicative of the author's philosophy. Applying his famous

673:

for the positive effect it has on the individual (art. 153).

640:(art. 31), the place where the soul is attached to the body.

711:. According to Alanen, Ryle describes the true man as the "

328:". The passions were experiences – now commonly called

552:

The work is itself divided into three parts, titled:

455:) but is incorporeal, while the body is physical (

887:According to Michel Meyer in his introduction to

407:Relationship between moral philosophy and science

917:94e. Année no. 3 (July–September 1989): 391–395.

875:. Translated by Jonathan Bennett. October 2010.

859:. Translated by Jonathan Bennett. October 2010.

843:. Translated by Jonathan Bennett. October 2010.

814:. Translated by Jonathan Bennett. October 2010.

624:The relationship between the body and the spirit

396:was written as a synthesis of this exchange.

283:

8:

290:

276:

28:

772:

525:It is with these six primary passions (

40:

616:is their relationship to Aristotelian

316:), completed in 1649 and dedicated to

302:In his final philosophical treatise,

7:

359:Origins and organization of the text

189:Rules for the Direction of the Mind

933:, philosophy for descartes Letters

915:Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale

467:, Descartes further explores this

25:

632:treatise is also the problem of

48:

904:", 53.3 (March, 2000): 657–683.

648:The combination of the passions

502:The organization of Descartes'

214:Meditations on First Philosophy

783:57.220 (April, 1982): 159–172.

1:

941:, modified for easier reading

378:Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia

318:Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia

498:Organization of the treatise

591:According to Michel Meyer,

372:Elisabeth of Bohemia (1636)

982:

242:Christina, Queen of Sweden

257:Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

112:Causal adequacy principle

761:Principles of Philosophy

688:The Passions of the Soul

677:Controlling the passions

417:philosophy of the Greeks

305:The Passions of the Soul

219:Principles of Philosophy

18:The Passions of the Soul

961:Works by René Descartes

744:Discourse on the Method

606:Discourse on the Method

204:Discourse on the Method

830:, meaning "suffering".

583:

570:Philosophical problems

523:

373:

313:

889:Les Passions de l'âme

733:Passions (philosophy)

587:Status of the subject

577:

512:

447:The notion of passion

371:

314:Les Passions de l'âme

939:Passions of the Soul

931:Passions of the Soul

873:Passions of the Soul

857:Passions of the Soul

841:Passions of the Soul

812:Passions of the Soul

713:ghost in the machine

519:Passions of the Soul

488:Passions of the Soul

480:Passions of the Soul

469:mysterious dichotomy

394:Passions of the Soul

224:Passions of the Soul

194:The Search for Truth

704:The Concept of Mind

628:The problem of the

364:Origins of the book

247:Nicolas Malebranche

117:Mind–body dichotomy

85:Doubt and certainty

755:Implicit cognition

584:

578:Title page of the

562:Specific Passions.

471:of mind and body.

374:

349:St. Thomas Aquinas

262:Francine Descartes

107:Trademark argument

902:Passions de l'Âme

871:Descartes, René.

855:Descartes, René.

839:Descartes, René.

810:Descartes, René.

750:Mind–body problem

738:Balloonist theory

686:The influence of

634:Cartesian dualism

461:Cartesian dualism

300:

299:

152:Balloonist theory

127:Coordinate system

122:Analytic geometry

16:(Redirected from

973:

918:

911:

905:

898:

892:

885:

879:

869:

863:

853:

847:

837:

831:

824:

818:

808:

802:

790:

784:

777:

292:

285:

278:

132:Cartesian circle

96:Cogito, ergo sum

52:

29:

21:

981:

980:

976:

975:

974:

972:

971:

970:

946:

945:

926:

921:

912:

908:

899:

895:

886:

882:

870:

866:

854:

850:

838:

834:

826:From the Latin

825:

821:

809:

805:

791:

787:

778:

774:

770:

729:

691:

679:

650:

626:

589:

572:

516:

500:

449:

424:natural science

413:Alexandre Koyré

409:

366:

361:

296:

267:

266:

237:

229:

228:

184:

176:

175:

147:Cartesian diver

75:Foundationalism

60:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

979:

977:

969:

968:

963:

958:

948:

947:

944:

943:

935:

925:

924:External links

922:

920:

919:

906:

893:

880:

864:

848:

832:

819:

803:

785:

771:

769:

766:

765:

764:

757:

752:

747:

740:

735:

728:

725:

690:

684:

678:

675:

649:

646:

625:

622:

588:

585:

571:

568:

564:

563:

560:

557:

499:

496:

484:nervous system

448:

445:

408:

405:

365:

362:

360:

357:

322:René Descartes

298:

297:

295:

294:

287:

280:

272:

269:

268:

265:

264:

259:

254:

252:Baruch Spinoza

249:

244:

238:

235:

234:

231:

230:

227:

226:

221:

216:

211:

206:

201:

196:

191:

185:

182:

181:

178:

177:

174:

173:

166:

159:

154:

149:

144:

139:

134:

129:

124:

119:

114:

109:

104:

99:

92:

90:Dream argument

87:

82:

77:

72:

67:

61:

58:

57:

54:

53:

45:

44:

42:René Descartes

38:

37:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

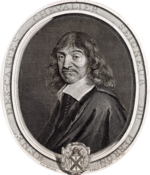

978:

967:

964:

962:

959:

957:

954:

953:

951:

942:

940:

936:

934:

932:

928:

927:

923:

916:

910:

907:

903:

897:

894:

890:

884:

881:

877:

874:

868:

865:

861:

858:

852:

849:

845:

842:

836:

833:

829:

823:

820:

816:

813:

807:

804:

801:

800:

795:

789:

786:

782:

776:

773:

767:

763:

762:

758:

756:

753:

751:

748:

746:

745:

741:

739:

736:

734:

731:

730:

726:

724:

722:

718:

714:

710:

706:

705:

700:

696:

689:

685:

683:

676:

674:

672:

668:

664:

658:

654:

647:

645:

641:

639:

635:

631:

623:

621:

619:

615:

610:

608:

607:

601:

599:

594:

586:

581:

576:

569:

567:

561:

558:

555:

554:

553:

550:

548:

544:

540:

536:

532:

528:

522:

520:

511:

509:

505:

497:

495:

491:

489:

485:

481:

476:

472:

470:

466:

462:

458:

454:

446:

444:

440:

437:

433:

429:

425:

420:

418:

414:

406:

404:

401:

397:

395:

391:

387:

383:

379:

370:

363:

358:

356:

354:

353:Thomas Hobbes

350:

346:

345:St. Augustine

341:

339:

335:

331:

327:

323:

319:

315:

311:

307:

306:

293:

288:

286:

281:

279:

274:

273:

271:

270:

263:

260:

258:

255:

253:

250:

248:

245:

243:

240:

239:

233:

232:

225:

222:

220:

217:

215:

212:

210:

207:

205:

202:

200:

197:

195:

192:

190:

187:

186:

180:

179:

172:

171:

167:

165:

164:

160:

158:

155:

153:

150:

148:

145:

143:

142:Rule of signs

140:

138:

135:

133:

130:

128:

125:

123:

120:

118:

115:

113:

110:

108:

105:

103:

100:

98:

97:

93:

91:

88:

86:

83:

81:

78:

76:

73:

71:

68:

66:

63:

62:

56:

55:

51:

47:

46:

43:

39:

35:

31:

30:

27:

19:

938:

930:

914:

909:

901:

896:

888:

883:

872:

867:

856:

851:

840:

835:

827:

822:

811:

806:

797:

788:

780:

775:

759:

742:

720:

708:

702:

701:, author of

699:Gilbert Ryle

697:argues that

695:Lilli Alanen

692:

687:

680:

659:

655:

651:

642:

638:pineal gland

629:

627:

613:

611:

604:

602:

592:

590:

579:

565:

551:

524:

521:, article 69

518:

517:—Descartes,

513:

503:

501:

492:

487:

479:

477:

473:

464:

456:

453:res cogitans

452:

450:

441:

428:Aristotelian

421:

410:

400:Amélie Rorty

398:

393:

375:

342:

326:the passions

304:

303:

301:

223:

209:La Géométrie

168:

163:Res cogitans

161:

157:Wax argument

94:

65:Cartesianism

26:

799:On the Soul

457:res extensa

170:Res extensa

70:Rationalism

956:1649 books

950:Categories

781:Philosophy

768:References

671:generosity

490:art. 10).

102:Evil demon

59:Philosophy

794:Aristotle

721:Discourse

618:teleology

598:Cartesian

436:Christian

382:happiness

199:The World

80:Mechanism

727:See also

709:Passions

663:contempt

630:Passions

614:Passions

600:system.

593:Passions

580:Passions

504:Passions

465:Passions

386:passions

330:emotions

34:a series

32:Part of

966:Emotion

547:sadness

332:in the

828:passio

667:esteem

545:, and

539:desire

527:wonder

508:method

390:ethics

388:, and

334:modern

310:French

236:People

137:Folium

717:Plato

463:. In

432:Stoic

338:Plato

183:Works

796:and

792:See

665:and

535:hate

531:love

434:and

351:and

543:joy

478:In

952::

541:,

537:,

533:,

529:,

392:.

384:,

355:.

347:,

340:.

320:,

312::

36:on

878:.

862:.

846:.

817:.

582:.

308:(

291:e

284:t

277:v

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.