326:

393:'s 1966 study of Commines has shown that the next five years, up to 1477, were the most prosperous from Commines's point of view, and the only ones when he truly had Louis's confidence. After Charles the Bold's death in 1477, the two men openly disagreed about how best to take political advantage of the situation. Commines himself admitted associating with some of the king's most prominent opponents and referred to another incident, in May 1478, when Louis reprimanded him for allegedly being open to bribery. Thereafter, much of his diplomatic work was done in the Italian arena, and he came into contact with

448:

432:), Commines's work was completed (first published in 1524 in Paris), and is considered a historical record of immense importance, largely because of its author's cynical and forthright attitude to the events and machinations he had witnessed. His writings reveal many of the less savoury aspects of the reign of Louis XI, and Commines related them without apology, insisting that the late king's virtues outweighed his vices. He is regarded as a major primary source for 15th-century European history.

302:

143:

51:

459:("For the honours always go to the winners"). Some have disputed whether his candid phrases disguise a deeper dishonesty. Yet at no time does he attempt to present himself as a hero, even when recounting his military career. His attitude to politics is one of pragmatism, and his ideas are practical and progressive. His reflections on the events he has witnessed are profound by comparison with those of

284:, recounts that one day, when they came home from hunting and were joking around as was their wont within the "family", Commines "ordered" the prince to remove Commines's boots as if he were a servant; laughing, the prince did so but then tossed the boot at Commines, and it bloodied his nose. Everyone in the Burgundian court started calling Commines "booted head". D'Israeli, in his 1824

292:"When we are versed in the history of the times, we often discover that memoir-writers have some secret poison in their hearts. Many, like Comines, have had the boot dashed on their nose. Personal rancour wonderfully enlivens the style... Memoirs are often dictated by its fiercest spirit; and then histories are composed from memoirs. Where is TRUTH? Not always in histories and memoirs!"

726:

309:

D'Israeli says

Commines so resented his nickname that it was the reason he suddenly left Burgundy and went into the service of the French king, but the financial incentives offered by Louis provide a more than adequate explanation: Commines was still heavily burdened with his father's debts. He fled

439:

are divided into "books", the first six of which were written between 1488 and 1494, and relate the course of events from the beginning of

Commines' career (1464) up to the death of King Louis. The remaining two books were written between 1497 and 1501 (printed in 1528), and deal with the Italian

400:

When Louis began to suffer ill-health, Commines was apparently welcomed back into the fold and performed personal services for the king. Many of his activities during the period seem to have involved a degree of secrecy; he was effectively acting as a kind of undercover agent. However, he never

401:

regained the level of intimacy with the king that he had previously enjoyed, and Louis's death in 1483, when

Commines was still only in his thirties, left him without many friends at court. Nevertheless, he retained a place on the royal council until 1485. Then, having been implicated in the

425:. Charles never allowed him the privileged position he had held under Louis, and he was once again used as an envoy to the Italian states. However, his personal affairs were still problematic, and his right to some of the possessions given him by Louis was subject to legal challenges.

249:, he mentions that King Edward was most beautiful, that he was very popular with his people and his subjects, but that he does not doubt at all (before the exile, Edward never heard any of Duke Charles' and his people's warnings). Commines praises Edward's best friend

213:, Philip's son who succeeded to the dukedom in 1467, and thereafter he moved in the most exalted circles, being party to many important decisions and present at history-making events. A key event in Commines's life seems to have been the meeting between Charles and

221:

in

October 1468. Although Commines's own account skates over the details, it is apparent from other contemporary sources that Louis believed Commines had saved his life. This may explain Louis's later enthusiasm in wooing him away from the Burgundians.

467:. Like Machiavelli, Commines aims to instruct the reader in statecraft, though from a slightly different viewpoint. In particular, he notes how Louis repeatedly got the better of the English, not by military might, but by political machination.

229:, then an English possession. It is unlikely that he ever visited England itself, what he knew of its politics and personalities coming mostly from meetings with exiles, both Yorkist and Lancastrian; these included

654:

Cristian Bratu, « Je, auteur de ce livre »: L'affirmation de soi chez les historiens, de l'Antiquité à la fin du Moyen Âge. Later

Medieval Europe Series (vol. 20). Leiden: Brill, 2019 (

325:

371:

of Berrie, Sables, and Olonne. Despite later reverses in the family's fortunes, on 13 August 1504 their only child, Jeanne de

Commines (d.1513), made a splendid marriage to the heir of

181:

which had belonged to the family of his paternal grandmother, Jeanne de

Waziers. His paternal grandfather, also named Colard van den Clyte (d. 1404), had been governor first of

129:). Neither a chronicler nor a historian in the usual sense of the word, his analyses of the contemporary political scene are what made him virtually unique in his own time.

687:

Cristian Bratu, "De la grande

Histoire à l'histoire personnelle: l'émergence de l'écriture autobiographique chez les historiens français du Moyen Age (XIIIe-XVe siècles)."

463:, who lived a century earlier. His psychological insights into the behaviour of kings are ahead of their time, reminiscent in some ways of the contemporaneous writings of

515:

318:. On the following morning, when Duke Charles discovered his servant and god-brother missing, he confiscated all of Commines' property. These were later given to

189:. However, the death of Commines' father in 1453 left him the orphaned owner of an estate saddled with enormous debts. In his teens he was taken into the care of

771:

405:, he was taken prisoner and kept in confinement for over two years, from January 1487 until March 1489. For some of that period, he was kept in an iron cage.

495:

761:

389:, Louis no doubt valued the inside information Commines was able to provide, and Commines quickly became one of the king's most trusted advisers.

751:

421:. (This title was not used until an edition of 1552.) By 1490, however, he was recovering his position at court and was in the service of King

125:

659:

169:

of

Renescure, Watten and Saint-Venant, Clyte became bailiff of Flanders for the Duke of Burgundy in 1436, and had been taken prisoner at the

250:

347:

of

Argenton, Varennes, and Maison-Rouge. When Hélène's sister, Colette de Chambes, was believed to have been poisoned by her aged husband

766:

356:

234:

710:

781:

776:

241:

during the latter's continental exile and later wrote a description of his appearance and character. Like other Burgundians,

796:

120:

786:

210:

791:

190:

617:

701:

756:

319:

269:, Commines mentions that Edward was a bastard and his real father was Blayborne (in French, Blayborgne), and that

684:. Juliana Dresvina and Nicholas Sparks, eds. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012): 231–259.

363:

most of his properties. Some of these he later gave to Commines for life, including the Princedom of Talmond in

288:, suggests that Commines's hatred for the duke of Burgundy poisoned everything he wrote about him, but comments:

276:

Commines was a great favorite with Duke Charles for seven years (going back to when he had still been Count of

31:

82:

447:

464:

441:

422:

379:

254:

194:

142:

746:

705:

625:(1957). "The Arts in Western Europe: Vernacular Literature in Western Europe". In G. R. Potter (ed.).

616:

Philippe de Commynes: The Reign of Louis XI 1461–83, translated with an introduction by Michael Jones

301:

741:

489:

270:

266:

258:

246:

238:

230:

390:

352:

262:

242:

170:

673:. Sini Kangas, Mia Korpiola, and Tuija Ainonen, eds. (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2013): 183–204.

429:

277:

214:

198:

158:

68:

680:: The Authorial Personae of French Medieval Historians from the 12th to the 15th centuries." In

348:

281:

655:

484:

394:

386:

376:

339:

218:

116:

560:

333:

Louis was generous in making up for those losses. On 27 January 1473 the king wed him to a

536:

261:

and "cruel". (In addition, according to Commines and rumours in Burgundy, Richard killed

460:

182:

50:

735:

622:

584:

669:: Authorial Persona and Authority in French Medieval Histories and Chronicles." In

671:

Authorities in the Middle Ages. Influence, Legitimacy and Power in Medieval Society

360:

178:

123:) and "the first critical and philosophical historian since classical times" (

161:), to an outwardly wealthy family. His parents were Colard van den Clyte (or

488:

154:

64:

720:

372:

311:

253:

as "le plus grand chevalier", "un sage chevalier", while overly attacks

17:

402:

193:(1419–1467), Duke of Burgundy, who was his godfather. He fought at the

364:

334:

315:

226:

115:; 1447 – 18 October 1511) was a writer and diplomat in the courts of

716:

446:

414:

324:

300:

186:

141:

108:

541:(in French). Paris (published 1901). 1489–1498. pp. 193–221

119:

and France. He has been called "the first truly modern writer" (

627:

The New Cambridge Modern History: I. The Renaissance 1493–1520

682:

Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles

629:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–185.

201:

in 1467 but in general seems to have kept a low profile.

413:

After his release, Commines was exiled to his estate at

455:

Commines' scepticism is summed up in his own words:

90:

75:

57:

41:

30:"Commines" redirects here. Not to be confused with

165:) and Marguerite d'Armuyden. In addition to being

209:In 1468, he became a knight in the household of

637:, ed. J. Blanchard, Geneve, Droz, 2007, 2 vol.

457:Car ceux qui gagnent en ont toujours l'honneur

8:

711:Bibliography of Philippe de Commines's works

355:, in a fit of jealousy over her affair with

499:. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). p. 774.

225:In 1470 Commines was sent on an embassy to

428:In 1498 (fifteen years after the death of

38:

510:

508:

506:

314:on 7 August 1472, and joined Louis near

476:

644:, ed. J. Blanchard, Geneve, Droz, 2001

562:Mémoires de Philippe de Commynes. T. 2

538:Mémoires de Philippe de Commynes. T. 1

273:was not eligible to claim the throne.

126:Oxford Companion to English Literature

27:Belgian writer, historian and diplomat

451:The deathbed of Philippe de Commines.

337:heiress, Hélène de Chambes (d.1532),

146:Coat of arms of Philippe de Commines.

7:

772:People from Nord (French department)

359:, Louis XI's brother, the king had

173:. Philippe took his surname from a

594:. Etienne Pattou. 26 February 2008

526:New York: Robert Appleton Company.

440:wars, ending in the death of King

25:

702:Biography of Philippe de Commines

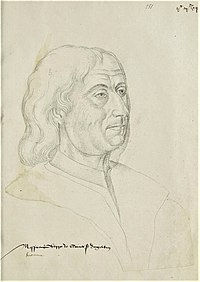

329:Engraving of Philippe de Commines

724:

706:New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia

49:

762:15th-century French historians

417:, where he began to write his

1:

752:Flemish writers (before 1830)

717:Works by Philippe de Commines

490:"Commines, Philippe de"

121:Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve

514:Louis René Bréhier (1908). "

280:). The 19th-century scholar

94:writer, diplomat, politician

723:(public domain audiobooks)

813:

107:or "Philippe de Comines";

29:

767:Medieval French diplomats

678:Clerc, Chevalier, Aucteur

375:'s most powerful family,

286:Curiosities of Literature

48:

385:As a long-time enemy of

667:Je, aucteur de ce livre

496:Encyclopædia Britannica

320:Philip I of Croÿ-Chimay

782:16th-century diplomats

777:15th-century diplomats

640:Philippe de Commynes,

633:Philippe de Commynes,

565:(in French). 1489–1498

452:

442:Charles VIII of France

423:Charles VIII of France

397:on several occasions.

330:

306:

294:

157:(in what was then the

147:

651:, Paris, Fayard, 2006

585:"Seigneurs d'Amboise"

520:Catholic Encyclopedia

450:

328:

304:

290:

235:Warwick the Kingmaker

145:

797:Princes in the Tower

649:Philippe de Commynes

516:Philippe de Commines

267:Olivier de la Marche

247:Olivier de la Marche

239:Edward IV of England

101:Philippe de Commines

83:Argenton-les-Vallées

43:Philippe de Commynes

787:French male writers

592:Racines et histoire

465:Niccolò Machiavelli

403:Orleanist rebellion

380:comte de Penthièvre

353:Viscount of Thouars

297:Service of Louis XI

259:murderer of princes

243:Georges Chastellain

237:. He also met King

195:Battle of Montlhéry

171:Battle of Agincourt

113:Philippus Cominaeus

792:Lords of the Manor

691:25 (2012): 85–117.

453:

430:Louis XI of France

331:

307:

305:Commines at prayer

215:Louis XI of France

199:Battle of Brusthem

159:county of Flanders

148:

757:French memoirists

676:Cristian Bratu, "

665:Cristian Bratu, "

660:978-90-04-39807-8

395:Lorenzo de Medici

357:Charles de Valois

98:

97:

16:(Redirected from

804:

728:

727:

647:Joël Blanchard,

630:

604:

603:

601:

599:

589:

581:

575:

574:

572:

570:

557:

551:

550:

548:

546:

533:

527:

512:

501:

500:

492:

481:

251:William Hastings

211:Charles the Bold

197:in 1465 and the

53:

39:

21:

812:

811:

807:

806:

805:

803:

802:

801:

732:

731:

725:

698:

621:

613:

608:

607:

597:

595:

587:

583:

582:

578:

568:

566:

559:

558:

554:

544:

542:

535:

534:

530:

513:

504:

485:Bémont, Charles

483:

482:

478:

473:

411:

349:Louis d'Amboise

299:

282:Isaac D'Israeli

207:

191:Philip the Good

140:

135:

86:

80:

71:

62:

44:

35:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

810:

808:

800:

799:

794:

789:

784:

779:

774:

769:

764:

759:

754:

749:

744:

734:

733:

730:

729:

714:

708:

697:

696:External links

694:

693:

692:

685:

674:

663:

652:

645:

638:

631:

619:

612:

609:

606:

605:

576:

552:

528:

502:

475:

474:

472:

469:

410:

407:

391:Jean Dufournet

377:René de Brosse

310:by night from

298:

295:

265:.) But unlike

206:

203:

139:

136:

134:

131:

96:

95:

92:

88:

87:

81:

77:

73:

72:

63:

59:

55:

54:

46:

45:

42:

26:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

809:

798:

795:

793:

790:

788:

785:

783:

780:

778:

775:

773:

770:

768:

765:

763:

760:

758:

755:

753:

750:

748:

745:

743:

740:

739:

737:

722:

718:

715:

712:

709:

707:

703:

700:

699:

695:

690:

686:

683:

679:

675:

672:

668:

664:

661:

657:

653:

650:

646:

643:

639:

636:

632:

628:

624:

620:

618:

615:

614:

610:

593:

586:

580:

577:

564:

563:

556:

553:

540:

539:

532:

529:

525:

521:

517:

511:

509:

507:

503:

498:

497:

491:

486:

480:

477:

470:

468:

466:

462:

458:

449:

445:

443:

438:

433:

431:

426:

424:

420:

416:

408:

406:

404:

398:

396:

392:

388:

383:

381:

378:

374:

370:

366:

362:

358:

354:

350:

346:

342:

341:

336:

327:

323:

321:

317:

313:

303:

296:

293:

289:

287:

283:

279:

274:

272:

268:

264:

263:King Henry VI

260:

256:

252:

248:

244:

240:

236:

232:

228:

223:

220:

216:

212:

204:

202:

200:

196:

192:

188:

184:

180:

177:on the river

176:

172:

168:

164:

160:

156:

152:

144:

137:

132:

130:

128:

127:

122:

118:

114:

110:

106:

102:

93:

91:Occupation(s)

89:

84:

78:

74:

70:

66:

60:

56:

52:

47:

40:

37:

33:

19:

747:1510s deaths

688:

681:

677:

670:

666:

648:

641:

634:

626:

623:Lawton, H.W.

596:. Retrieved

591:

579:

567:. Retrieved

561:

555:

543:. Retrieved

537:

531:

523:

519:

494:

479:

456:

454:

436:

434:

427:

418:

412:

399:

384:

368:

344:

338:

332:

308:

291:

285:

275:

224:

208:

185:and then of

174:

166:

162:

153:was born at

150:

149:

124:

112:

104:

100:

99:

36:

742:1447 births

713:, in French

689:Mediävistik

369:seigneuries

361:confiscated

345:seigneuries

271:Henry Tudor

255:Richard III

231:Henry Tudor

163:de La Clyte

105:de Commynes

736:Categories

611:References

569:4 November

545:4 November

382:(d.1524).

367:, and the

175:seigneurie

138:Early life

461:Froissart

278:Charolais

155:Renescure

133:Biography

65:Renescure

721:LibriVox

635:Mémoires

487:(1911).

437:Mémoires

419:Mémoires

409:Mémoires

387:Burgundy

373:Brittany

335:Poitevin

312:Normandy

205:Burgundy

167:seigneur

151:Commines

117:Burgundy

85:, Poitou

69:Flanders

18:Commines

704:at the

642:Lettres

343:of the

219:Péronne

79:c. 1511

32:Comines

658:

598:8 July

518:". In

365:Poitou

316:Angers

227:Calais

183:Cassel

588:(PDF)

471:Notes

415:Dreux

187:Lille

109:Latin

656:ISBN

600:2008

571:2021

547:2021

435:The

340:dame

233:and

103:(or

76:Died

61:1447

58:Born

719:at

257:as

217:at

179:Lys

738::

662:).

590:.

524:4.

522:.

505:^

493:.

444:.

351:,

322:.

245:,

111::

67:,

602:.

573:.

549:.

34:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.