135:

make conclusions regarding environmental adaptations of a species. The data provided from these studies can, however, support and enrich the understanding of a species' ecomorphological adaptations. For instance, the relationship between the organization of the jaw lever-arm system, mouth size, and jaw muscle force generation and the feeding behaviour of sunfish has been investigated. Work of this variety lends scientific support to seemingly intuitive concepts. For instance, increases in mouth size correspond to an increase in prey size. However, less obvious trends also exist. The prey-size of fish does not seem to correlate so much to body size as to the characteristics of the feeding apparatus.

115:

194:

84:, was focal point of morphological research. However, during the 1930s and 40s morphology as a field shrank. This was likely due to the emergence of new areas of biological inquiry enabled by new techniques. The 1950s brought about not only a change in the approach of morphological studies, resulting in the development of evolutionary morphology in the form of theoretical questions, and a resurgence of interest in the field.

130:. Ecomorphology, on the other hand, refers to those features which can be shown to derive from the ecology surrounding the species. In other words, functional morphology focuses heavily on the relationship between form and function whereas ecomorphology is interested in the form and the influences from which it arises. Functional morphology studies often investigate relationships between the form of

290:

The study of evolutionary morphology concerns changes in species morphology over time in order to become better suited to their environment. These studies are conducted by comparing the features of species groups to provide a historical narrative of the changes in morphology observed with changes in

295:

must first be known before a history of evolutionary morphology can be observed. This area of biology serves only to provide a nominal explanation of evolutionary biology, as a more in depth explanation of species history is required to provide a thorough explanation of evolution within a species.

134:

and physical properties such as force generation and joint mobility. This means that functional morphology experiments may be done under laboratory conditions whereas ecomorphological experiments may not. Moreover, studies of functional morphology themselves provide insufficient data upon which to

92:

allowed for observation of the integration of muscle activities. Together, these methodologies allowed morphologists to better delve into the intricacies of their study. It was then, in the 1950s and 60s, that ecologists began to use morphological measures to study evolutionary and ecological

304:

Suggestions have been made that the correlations between species biodiversity and particular environments may not necessarily be due to ecomorphology, but rather a conscious decision made by species to relocate to an ecosystem to which their morphologies are better suited. However, there are

305:

currently no studies that provide concrete evidence to support this theory. Studies have been conducted to predict fish habitat preference based on body morphology, but no definitive distinction could be made between correlation and causation of fish habitat preference.

503:

Sibbing, F., L. Nagelkerke, and J. Osse. 1994. Ecomorphology as a tool in fisheries-Identification and ecotyping of Lake Tana Barbs (Barbus-Intermedius COmplex), Ethiopia. Netherlands

Journal of Agricultural Science 42:77–85. Royal Netherlands Soc Agr

612:

Plummer, T. W., Bishop, L. C., Hertel, F. 2008. Habitat preference of extant

African bovids based on astragalus morphology: operationalizing ecomorphology for palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Journal of Archaeological Science 35(11): 3016–3027

64:

Current ecomorphological research focuses on a functional approach and application to the science. A broadening of this field welcomes further research in the debate regarding differences between both the ecological and morphological makeup of an

391:

Karr, J.R. and James, F.C. 1975. Eco-morphological configurations and convergent evolution of species and communities; in

Ecology and Evolution of Communities (eds). M.L. Cody and J.M. Diamond. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

143:

The work above is just one example of an ecomorphology based behavioural study. Studies of this variety are becoming increasingly important in the field. Behavioural studies interrelate functional and eco-morphology. Features such as

197:

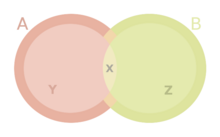

Simplified representation of an ecological niche where A and B show the fundamental niches of species 1 and species 2 respectively. Z the realised niche of species 2 and X the niche overlap, where competition occurs among

157:

ecomorphology. Indeed, gut volume was found to correlate positively to increasing metabolic rate. Ecomorphological studies can often be used to determine to presence of parasites in a given temporospatial context as

152:

and in studying birds. Other studies attempt to relate ecomorphological findings with the dietary habits of species. Griffen and

Mosblack (2011) investigated differences in diet and consumption rate as a function of

281:

dependent. Evidence also suggests that further study of the ecomorphology of previously existing habitats may be useful in determining the phylogenetic risk associated with species living in a specific habitat.

633:

Betz, O. (2006), Ecomorphology: Integration of form, function, and ecology in the analysis of morphological structures, Mitteilungen der

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemeine und Angewandte Entomologie 15,

262:. The morphologies of paleo-species found at a location help to make inferences about the previous appearance and properties of that habitat. Research using this approach has been widely conducted using

53:

exhibited by an organism are directly or indirectly influenced by their environment, and ecomorphology aims to identify the differences. Current research places emphasis on linking morphology and

273:. Plummer and Bishop conducted a study using extant African bovids to investigate the animal’s paleoenvironment based on their habitat preference. The strong correlation found between bovid

527:

526:

Goodman, B. A., and P. T. J. Johnson. 2011. Ecomorphology and disease: cryptic effects of parasitism on host habitat use, thermoregulation, and predator avoidance. Ecology 92:542–548.

516:

505:

515:

Griffen, B. D., and H. Mosblack. 2011. Predicting diet and consumption rate differences between and within species using gut ecomorphology. The

Journal of animal ecology 80:854–63.

413:

542:

Norton, S. F., J. J. Luczkovich, and P. J. Motta. 1995. The role of ecomorphological studies in the comparative biology of fishes. Environmental

Biology of Fishes 44:287–304.

492:

Moermond, T., and J. Denslow. 1983. Fruit choice in neotropical birds: effects of fruit type and accessibility on selectivity. The

Journal of Animal Ecology 52(2): 407–420.

439:

601:

Scott, R. S., and W. A. Barr. 2014. Ecomorphology and phylogenetic risk: Implications for habitat reconstruction using fossil bovids. Journal of human evolution 73:47–57

624:

Chan, M. D. 2001. Fish ecomorphology: predicting habitat preferences of stream fishes from their body shape. Virginia

Polytechnic Institute and State University.

381:

438:

Bock, W., G. Lanzavecchia, and R. Valvassori. 1991. Levels of complexity and organismal organization. Selected

Symposia and Monographs UZI. Vol 5 181–212.

246:, wide distribution, the ability to occupy various ecological niches, and obvious morphological differences. Ecomorphology is also often used to study the

401:

169:

Other current work within ecomorphology focuses on broadening the knowledge base to allow for ecomorphological studies to incorporate a wider range of

587:

Fryer, G. T. and Iles, T. D. The cichlid fishes of the great lakes of Africa: their biology and evolution. 1972. Oliver and Boyd, Cornell University.

258:

The history of how a species has undergone morphological adaptations to better suit its ecological role can be used to draw conclusions about its

148:

ability in foraging birds have been shown to affect dietary preferences by studies of this type. Behavioural studies are particularly common in

77:

The roots of ecomorphology date back to the late 19th century. Then, description and comparison of morphological form, primarily for use in

242:

conducted by Fryer and Iles were some of the first to demonstrate ecomorphology, . This is largely due to cichlids having great

322:

93:

questions. This culminated in Karr and James coining the term "ecomorphology" in 1975. The following year the links between

126:

Functional morphology differs from ecomorphology in that it deals with the features arising from form at varying levels of

412:

Leisler, B. 1977. Morphological Aspects of Ecological Specializations in Bird Genera. American Zoologist 19(3): 1014–1014.

646:

177:, and systems. Much current work also focuses on the integration of ecomorphology with other comparative fields such as

450:

Wainwright, P. C. (1996). "Ecological Explanation through Functional Morphology: The Feeding Biology of Sunfishes".

559:"Evolution of ecological structure of anole communities in tropical rain forests from north-western South America"

81:

424:

222:, demonstrate different reproductive techniques, and have various sensory modalities. Studies conducted on

127:

154:

85:

588:

348:

57:

by measuring the performance of traits (i.e. sprint speed, bite force, etc.) associated behaviours, and

118:

Ecomorphological relationships have been demonstrated between jaw structure and the feeding biology of

202:

An understanding of ecomorphology is necessary when investigating both the origins of and reasons for

614:

602:

459:

211:

42:

259:

247:

27:

Study of the relation between the ecological role of an individual and its morphologic adaptations

475:

423:

Bock, W. Van Walhert, J. 1965. The role of adaptive mechanisms in the origin of higher levels of

292:

270:

558:

230:

frequently investigate the extent to which species morphology is influenced by their ecology.

145:

58:

369:

Bock, W. J. 1994. Concepts and methods in ecomorphology. Journal of Biosciences 19:403–413.

570:

467:

219:

89:

54:

428:

131:

463:

114:

640:

178:

119:

88:

and x-ray cinematography began to allow for observations of movements of parts while

380:

Beer, G. 1954. Archaeopteryx and evolution. The Advancement of Science 11: 160–170.

326:

243:

235:

234:

are often used to study ecomorphology due to their long evolutionary history, high

227:

203:

574:

238:, and multi-stage life cycle. Studies on the morphological diversity of African

231:

17:

543:

370:

193:

159:

94:

46:

38:

274:

149:

557:

Moreno-Arias, Rafael A.; Bloor, Paul; Calderón-Espinosa, Martha L. (2020).

349:"The role of ecomorphological studies in the comparative biology of fishes"

101:

were finally established creating the foundations of modern ecomorphology.

182:

66:

479:

277:

and habitat preference suggests that linking morphology and habitat is

263:

239:

223:

215:

207:

170:

163:

98:

50:

402:

Bock, W. 1977. Toward an ecological morphology. Vogelwarte 29: 127–135

266:

625:

493:

471:

278:

192:

174:

113:

210:. Ecomorphology is fundamental for understanding changes in the

78:

291:

habitat. A background history of a species features and

45:

adaptations. The term "morphological" here is in the

250:of a species and/or its evolutionary morphology.

185:to better understand evolutionary morphology.

254:Paleohabitat determination from ecomorphology

37:is the study of the relationship between the

8:

269:due to their large skeletons and extensive

563:Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

538:

536:

534:

365:

363:

361:

597:

595:

552:

550:

314:

300:Ecomorphology versus habitat preference

110:Ecomorphology and functional morphology

427:. Systematic Biology 14(4): 272–287.

7:

218:in which subsets occupy different

25:

49:context. Both the morphology and

61:outcomes of the relationships.

354:. University of South Florida.

1:

189:Applications of ecomorphology

73:Development of ecomorphology

325:. About.com. Archived from

663:

575:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa006

86:High-speed cinematography

41:of an individual and its

162:presence can alter host

286:Evolutionary morphology

199:

123:

196:

117:

35:ecological morphology

647:Comparative anatomy

464:1996Ecol...77.1336W

139:Behavioural studies

200:

124:

347:Norton, Stephen.

271:species radiation

220:ecological niches

16:(Redirected from

654:

627:

622:

616:

610:

604:

599:

590:

585:

579:

578:

554:

545:

540:

529:

524:

518:

513:

507:

501:

495:

490:

484:

483:

458:(5): 1336–1343.

447:

441:

436:

430:

421:

415:

410:

404:

399:

393:

389:

383:

378:

372:

367:

356:

355:

353:

344:

338:

337:

335:

334:

319:

90:electromyography

55:ecological niche

21:

18:Ecomorphological

662:

661:

657:

656:

655:

653:

652:

651:

637:

636:

631:

630:

623:

619:

611:

607:

600:

593:

586:

582:

556:

555:

548:

541:

532:

525:

521:

514:

510:

502:

498:

491:

487:

472:10.2307/2265531

449:

448:

444:

437:

433:

422:

418:

411:

407:

400:

396:

390:

386:

379:

375:

368:

359:

351:

346:

345:

341:

332:

330:

323:"Ecomorphology"

321:

320:

316:

311:

302:

288:

256:

191:

141:

132:Skeletal muscle

112:

107:

97:morphology and

75:

39:ecological role

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

660:

658:

650:

649:

639:

638:

629:

628:

617:

605:

591:

580:

569:(1): 298–313.

546:

530:

519:

508:

496:

485:

442:

431:

416:

405:

394:

384:

373:

357:

339:

313:

312:

310:

307:

301:

298:

287:

284:

255:

252:

190:

187:

140:

137:

111:

108:

106:

103:

82:classification

74:

71:

26:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

659:

648:

645:

644:

642:

635:

626:

621:

618:

615:

609:

606:

603:

598:

596:

592:

589:

584:

581:

576:

572:

568:

564:

560:

553:

551:

547:

544:

539:

537:

535:

531:

528:

523:

520:

517:

512:

509:

506:

500:

497:

494:

489:

486:

481:

477:

473:

469:

465:

461:

457:

453:

446:

443:

440:

435:

432:

429:

426:

420:

417:

414:

409:

406:

403:

398:

395:

388:

385:

382:

377:

374:

371:

366:

364:

362:

358:

350:

343:

340:

329:on 2013-05-14

328:

324:

318:

315:

308:

306:

299:

297:

294:

285:

283:

280:

276:

272:

268:

265:

261:

253:

251:

249:

245:

241:

237:

233:

229:

225:

221:

217:

213:

209:

205:

195:

188:

186:

184:

180:

179:phylogenetics

176:

172:

167:

165:

161:

156:

151:

147:

138:

136:

133:

129:

121:

116:

109:

105:Ecomorphology

104:

102:

100:

96:

91:

87:

83:

80:

72:

70:

68:

62:

60:

56:

52:

48:

44:

43:morphological

40:

36:

32:

31:Ecomorphology

19:

632:

620:

608:

583:

566:

562:

522:

511:

499:

488:

455:

451:

445:

434:

425:organisation

419:

408:

397:

387:

376:

342:

331:. Retrieved

327:the original

317:

303:

289:

260:paleohabitat

257:

248:paleohabitat

244:biodiversity

236:biodiversity

228:biodiversity

204:biodiversity

201:

183:ontogenetics

168:

142:

128:organisation

125:

76:

63:

34:

30:

29:

232:Bony fishes

333:2013-05-21

309:References

226:with high

212:morphology

146:locomotory

95:vertebrate

47:anatomical

275:phylogeny

206:within a

150:fisheries

641:Category

634:409-416.

293:homology

240:cichlids

198:species.

171:habitats

160:parasite

67:organism

480:2265531

460:Bibcode

452:Ecology

392:258–291

267:fossils

224:species

216:species

208:species

164:habitat

120:sunfish

99:ecology

59:fitness

51:ecology

478:

476:JSTOR

352:(PDF)

279:taxon

264:bovid

214:of a

166:use.

79:avian

504:Sci.

181:and

175:taxa

571:doi

567:190

468:doi

155:gut

33:or

643::

594:^

565:.

561:.

549:^

533:^

474:.

466:.

456:77

454:.

360:^

173:,

69:.

577:.

573::

482:.

470::

462::

336:.

122:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.