375:. It has been argued that desire is the more fundamental notion and that preferences are to be defined in terms of desires. For this to work, desire has to be understood as involving a degree or intensity. Given this assumption, a preference can be defined as a comparison of two desires. That Nadia prefers tea over coffee, for example, just means that her desire for tea is stronger than her desire for coffee. One argument for this approach is due to considerations of parsimony: a great number of preferences can be derived from a very small number of desires. One objection to this theory is that our introspective access is much more immediate in cases of preferences than in cases of desires. So it is usually much easier for us to know which of two options we prefer than to know the degree with which we desire a particular object. This consideration has been used to suggest that maybe preference, and not desire, is the more fundamental notion.

387:, the term can be used to describe when a company pays a specific creditor or group of creditors. From doing this, that creditor(s) is made better off, than other creditors. After paying the 'preferred creditor', the company seeks to go into formal insolvency like an administration or liquidation. There must be a desire to make the creditor better off, for them to be a preference. If the preference is proven, legal action can occur. It is a wrongful act of trading. Disqualification is a risk. Preference arises within the context of the principle maintaining that one of the main objectives in the winding up of an insolvent company is to ensure the equal treatment of creditors. The rules on preferences allow paying up their creditors as insolvency looms, but that it must prove that the transaction is a result of ordinary commercial considerations. Also, under the English

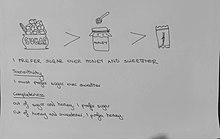

158:. The first axiom of transitivity refers to consistency between preferences, such that if x is preferred to y and y is preferred to z, then x has to be preferred to z. The second axiom of completeness describes that a relationship must exist between two options, such that x must be preferred to y or y must be preferred to x, or is indifferent between them. For example, if I prefer sugar to honey and honey to sweetener then I must prefer sugar to sweetener to satisfy transitivity and I must have a preference between the items to satisfy completeness. Under the axiom of completeness, an individual cannot lack a preference between any two options.

189:, then he is maximizing the expected value of a utility function. In utility theory, preference relates to decision makers' attitudes towards rewards and hazards. The specific varieties are classified into three categories: 1) risk-averse, that is, equal gains and losses, with investors participating when the loss probability is less than 50%; 2) the risk-taking kind, which is the polar opposite of type 1); 3) Relatively risk-neutral, in the sense that the introduction of risk has no clear association with the decision maker's choice.

162:

391:, if a creditor was proven to have forced the company to pay, the resulting payment would not be considered a preference since it would not constitute unfairness. It is the decision to give a preference, rather than the giving of the preference pursuant to that decision, which must be influenced by the desire to produce the effect of the preference. For these purposes, therefore, the relevant time is the date of the decision, not the date of giving the preference.

1750:

97:, even unconsciously. Consequently, preference can be affected by a person's surroundings and upbringing in terms of geographical location, cultural background, religious beliefs, and education. These factors are found to affect preference as repeated exposure to a certain idea or concept correlates with a positive preference.

149:

Consumer preference, or consumers' preference for particular brands over identical products and services, is an important notion in the psychological influence of consumption. Consumer preferences have three properties: completeness, transitivity and non-satiation. For a preference to be rational, it

309:

Individual preferences can be represented as an indifference curve given the underlying assumptions. Indifference curves graphically depict all product combinations that yield the same amount of usefulness. Indifference curves allow us to graphically define and rank all possible combinations of two

370:

are two closely related notions: they are both conative states that determine our behavior. The difference between the two is that desires are directed at one object while preferences concern a comparison between two alternatives, of which one is preferred to the other. The focus on preferences

92:

process. The term is also used to mean evaluative judgment in the sense of liking or disliking an object, as in

Scherer (2005), which is the most typical definition employed in psychology. It does not mean that a preference is necessarily stable over time. Preference can be notably modified by

342:

In psychology, risk preference is occasionally characterised as the proclivity to engage in a behaviour or activity that is advantageous but may involve some potential loss, such as substance abuse or criminal action that may bring significant bodily and mental harm to the individual.

173:. This is because the axioms allow for preferences to be ordered into one equivalent ordering with no preference cycles. Maximising utility does not imply maximise happiness, rather it is an optimisation of the available options based on an individual's preferences. The so-called

281:

describes an alternative approach to predicting human behaviour by using psychological theory which explores deviations from rational preferences and the standard economic model. It also recognises that rational preferences and choices are limited by

346:

In economics, risk preference refers to a proclivity to engage in behaviours or activities that entail greater variance returns, regardless of whether they be gains or losses, and are frequently associated with monetary rewards involving lotteries.

350:

There are two different traditions of measuring preference for risk, the revealed and stated preference traditions, which coexist in psychology, and to some extent in economics as well.

69:. The difference between the two is that desires are directed at one object while preferences concern a comparison between two alternatives, of which one is preferred to the other.

511:

Coppin, G., Delplanque, S., Cayeux, I., Porcherot, C., & Sander, D. (2010). "I'm no longer torn after choice: How explicit choices can implicitly shape preferences for odors".

264:

238:

218:

1338:"The Decision Making Individual Differences Inventory and guidelines for the study of individual differences in judgment and decision-making research"

353:

Risk preference evaluated from stated preferences emerges as a concept with significant temporal stability, but revealed preference measures do not.

146:, where individuals make decisions based on rational preferences which are aligned with their self-interests in order to achieve an optimal outcome.

1636:

981:

Kalter, Frank; Kroneberg, Clemens (2012). "Rational Choice Theory and

Empirical Research: Methodological and Theoretical Contributions in Europe".

1715:

1315:

1106:

192:

The mathematical foundations of most common types of preferences — that are representable by quadratic or additive functions — laid down by

1698:

1669:

806:

426:

1771:

564:

Allan, Bentley B. (2019). "Paradigm and nexus: neoclassical economics and the growth imperative in the World Bank, 1948-2000".

927:

Tangian, Andranik (2002). "Constructing a quasi-concave quadratic objective function from interviewing a decision maker".

1791:

1295:

1159:"Loss aversion, overconfidence of investors and their impact on market performance evidence from the US stock markets"

737:

333:

174:

31:

273:) does not always accurately predict human behaviour because it makes unrealistic assumptions. In response to this,

485:

Sharot, T.; De

Martino, B.; & Dolan, R. J. (2009). "How choice reveals and shapes expected hedonic outcome".

410:

405:

155:

62:

1786:

1209:

294:

are rules of thumb such as elimination by aspects which are used to make decisions rather than maximising the

88:, preferences refer to an individual's attitude towards a set of objects, typically reflected in an explicit

274:

1744:

169:

If preferences are both transitive and complete, the relationship between preference can be described by a

691:

655:

Schotter, Andrew (2006). "Strong and Wrong: The Use of

Rational Choice Theory in Experimental Economics".

270:

161:

143:

139:

106:

57:. For example, someone prefers A over B if they would rather choose A than B. Preferences are central to

416:

278:

200:

to develop methods for their elicitation. In particular, additive and quadratic preference functions in

1008:

England, Paula (1989). "A feminist critique of rational-choice theories: Implications for sociology".

76:, the term is used to determine which outstanding obligation the insolvent party has to settle first.

1241:"The influence of neuroscience on US Supreme Court decisions about adolescents' criminal culpability"

388:

151:

904:

Debreu, Gérard (1960). "Topological methods in cardinal utility theory". In Arrow, Kenneth (ed.).

142:

to provide observable evidence in relation to people's actions. These actions can be described by

1781:

1553:

1438:

1367:

1276:

1190:

1139:

1079:

1025:

886:

851:

760:

672:

634:

581:

339:

Risk tolerance is a critical component of personal financial planning, that is, risk preference.

306:

also violate the assumption of rational preferences by causing individuals to act irrationally.

123:

refers to the set of assumptions related to ordering some alternatives, based on the degree of

1694:

1665:

1507:

1499:

1419:

1359:

1311:

1268:

1260:

1221:

1102:

843:

802:

546:

182:

65:

use preference relation for decision-making. As connative states, they are closely related to

1575:

954:

Tangian, Andranik (2004). "A model for ordinally constructing additive objective functions".

1776:

1545:

1489:

1481:

1450:

1409:

1401:

1349:

1303:

1252:

1180:

1170:

1131:

1071:

1017:

990:

963:

936:

909:

878:

835:

752:

703:

664:

626:

573:

538:

468:

295:

197:

193:

185:

in 1944, explains that so long as an agent's preferences over risky options follow a set of

178:

170:

1336:

Appelt, Kirstin C.; Milch, Kerry F.; Handgraaf, Michel J. J.; Weber, Elke U. (April 2011).

220:

variables can be constructed from interviews, where questions are aimed at tracing totally

1754:

1749:

799:

The

Cognitive Basis of Institutions: A Synthesis of Behavioral and Institutional Economics

372:

277:

argue that it provides a normative model for people to adjust and optimise their actions.

89:

58:

243:

823:

692:"Indifference or indecisiveness? Choice-theoretic foundations of incomplete preferences"

332:

Risk preference is defined as how much risk a person is prepared to accept based on the

1686:

1414:

459:

Scherer, Klaus R. (December 2005). "What are emotions? And how can they be measured?".

223:

203:

116:

1468:

Mata, Rui; Frey, Renato; Richter, David; Schupp, Jürgen; Hertwig, Ralph (2018-05-01).

1307:

994:

967:

940:

913:

617:

Bossert, Walter; Kotaro, Suzumura (2009). "External Norms and

Rationality of Choice".

1765:

1557:

1494:

1194:

1143:

1083:

1029:

855:

585:

498:

Brehm, J. W. (1956). "Post-decision changes in desirability of choice alternatives".

303:

128:

1280:

1043:

Herfeld, Catherine (2021). "Revisiting the criticisms of rational choice theories".

676:

638:

1469:

1371:

764:

136:

577:

54:

1739:

1122:

Grandori, Anna (2010). "A rational heuristic model of economic decision making".

1534:"Preferences Vs. Desires: Debating the Fundamental Structure of Conative States"

526:

1454:

1175:

1158:

1549:

1354:

1337:

756:

707:

630:

400:

384:

291:

283:

85:

73:

46:

38:

1609:

1503:

1363:

1264:

1225:

1135:

1075:

847:

668:

550:

472:

124:

112:

42:

1511:

1423:

1385:

Beshears, John; Choi, James; Laibson, David; Madrian, Brigitte (May 2008).

1272:

1101:(3 ed.). United Kingdom: Macmillan Education Limited. pp. 25–37.

320:

Greater transitivity indicates that the indifference curves do not overlap.

1485:

1240:

269:

Empirical evidence has shown that the usage of rational preferences (and

1386:

1185:

17:

1021:

890:

366:

132:

66:

1533:

839:

778:

Kirsh, Yoram (2017). "Utility and

Happiness in a Prosperous Society".

323:

A propensity for diversity causes indifference curves to curve inward.

421:

299:

287:

94:

1256:

1208:

Aguirre Sotelo, Jose

Antonio Manuel; Block, Walter E. (2014-12-31).

882:

869:

Debreu, Gérard (1952). "Definite and semidefinite quadratic forms".

1405:

542:

266:

coordinate planes without referring to cardinal utility estimates.

186:

160:

30:

This article is about the psychological term. For other uses, see

53:

is a technical term usually used in relation to choosing between

1302:, vol. 12, Bingley: Emerald (MCB UP ), pp. 41–196,

1740:

Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on 'Preferences'

1691:

Corporate

Finance Law: Principles and Policy, Second Edition

1210:"Indifference Curve Analysis: The Correct and the Incorrect"

738:"The theory of judgment aggregation: an introductory review"

601:

Rational Choice Theory and Organizational Theory: A Critique

1062:

Case, Karl (2008). "A Response to Guerrien and Benicourt".

61:

because of this relation to behavior. Some methods such as

824:"Why and Under What Conditions Does Loss Aversion Emerge?"

135:

they provide. The concept of preferences is used in post-

1758:(white paper from International Communications Research)

1163:

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

780:

OUI – Institute for Policy Analysis Working Paper Series

317:

If more is better, the indifference curve dips downward.

908:. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 16–26.

1437:

Charness, Gary; Gneezy, Uri; Imas, Alex (March 2013).

246:

226:

206:

1637:"What Is A Preference Under The Insolvency Act 1986"

1439:"Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences"

1294:Harrison, Glenn W.; Rutström, E. Elisabet (2008),

371:instead of desires is very common in the field of

258:

232:

212:

165:An example of transitive and complete preferences.

1664:. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 368.

906:Mathematical Methods in the Social Sciences,1959

527:"Affective and Cognitive Factors in Preferences"

1716:"Green v Ireland [2011] EWHC 1305 (Ch)"

1616:. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University

1443:Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

525:Zajonc, Robert B.; Markus, Hazel (1982-09-01).

1693:. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 111.

8:

1603:

1601:

1599:

1597:

1157:Bouteska, Ahmed; Regaieg, Boutheina (2020).

723:Utility Maximization, Choice and Preferences

445:Lichtenstein, S.; & Slovic, P. (2006).

1569:

1567:

1527:

1525:

1523:

1521:

1493:

1470:"Risk Preference: A View from Psychology"

1413:

1353:

1184:

1174:

1064:The Review of Radical Political Economics

566:Review of International Political Economy

500:Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology

245:

225:

205:

956:European Journal of Operational Research

929:European Journal of Operational Research

603:. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 1–13.

449:. New York: Cambridge University Press.

1614:The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

801:. London: Academic Press. p. 137.

725:(2 ed.). Springer. pp. 17–52.

438:

1655:

1653:

650:

648:

7:

1580:Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

612:

610:

313:The graph's three main points are:

93:decision-making processes, such as

27:To like one thing more than another

1300:Research in Experimental Economics

25:

1400:(8–9). Cambridge, MA: 1787–1794.

1296:"Risk Aversion in the Laboratory"

1239:Steinberg, Laurence (July 2013).

1099:A Course in Behavioural Economics

995:10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145441

1748:

1474:Journal of Economic Perspectives

1387:"How are Preferences Revealed?"

828:Japanese Psychological Research

822:Nagaya, Kazuhisa (2021-10-15).

657:Journal of Theoretical Politics

447:The construction of preference

1:

1745:Customer preference formation

1308:10.1016/s0193-2306(08)00003-3

968:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00413-2

941:10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00185-0

914:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00413-2

578:10.1080/09692290.2018.1543719

302:such as reference points and

175:Expected Utility Theory (EUT)

1342:Judgment and Decision Making

531:Journal of Consumer Research

413:(in artificial intelligence)

336:or pleasure of the outcome.

1662:Company Law, Fourth Edition

1394:Journal of Public Economics

1245:Nature Reviews Neuroscience

696:Games and Economic Behavior

150:must satisfy the axioms of

32:Preference (disambiguation)

1808:

1455:10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.023

1176:10.1108/JEFAS-07-2017-0081

983:Annual Review of Sociology

461:Social Science Information

240:2D-indifference curves in

177:, which was introduced by

131:, morality, enjoyment, or

104:

29:

1660:Hannigan, Brenda (2015).

1550:10.1017/S0266267115000115

1532:Schulz, Armin W. (2015).

1495:21.11116/0000-0001-5038-6

1355:10.1017/S1930297500001455

757:10.1007/s11229-011-0025-3

708:10.1016/j.geb.2005.06.007

631:10.1017/S0266267109990010

411:Preference-based planning

406:Ordinal Priority Approach

156:Completeness (statistics)

63:Ordinal Priority Approach

1538:Economics and Philosophy

1136:10.1177/1043463110383972

1076:10.1177/0486613408320324

1010:The American Sociologist

736:List, Christian (2012).

721:Aleskerov, Fuad (2007).

669:10.1177/0951629806067455

619:Economics and Philosophy

473:10.1177/0539018405058216

1608:Schroeder, Tim (2020).

1124:Rationality and Society

797:Teraji, Shinji (2018).

487:Journal of Neuroscience

275:neoclassical economists

1772:Psychological attitude

271:Rational Choice Theory

260:

234:

214:

166:

144:Rational Choice Theory

140:neoclassical economics

107:Preference (economics)

1214:Oeconomia Copernicana

1097:Angner, Erik (2021).

513:Psychological Science

417:Preference revelation

279:Behavioural economics

261:

235:

215:

164:

1486:10.1257/jep.32.2.155

690:Eliaz, Kfir (2006).

244:

224:

204:

427:Pairwise comparison

389:Insolvency Act 1986

357:Relation to desires

259:{\displaystyle n-1}

1792:Concepts in ethics

1685:Gullifer, Louise;

1045:Philosophy Compass

1022:10.1007/BF02697784

599:Zey, Mary (1998).

256:

230:

210:

167:

1757:

1317:978-0-7623-1384-6

1108:978-1-352-01080-0

840:10.1111/jpr.12385

233:{\displaystyle n}

213:{\displaystyle n}

183:Oskar Morgenstern

16:(Redirected from

1799:

1753:

1752:

1727:

1726:

1724:

1722:

1711:

1705:

1704:

1682:

1676:

1675:

1657:

1648:

1647:

1645:

1643:

1632:

1626:

1625:

1623:

1621:

1605:

1592:

1591:

1589:

1587:

1574:Pettit, Philip.

1571:

1562:

1561:

1529:

1516:

1515:

1497:

1465:

1459:

1458:

1434:

1428:

1427:

1417:

1391:

1382:

1376:

1375:

1357:

1333:

1327:

1326:

1325:

1324:

1291:

1285:

1284:

1236:

1230:

1229:

1205:

1199:

1198:

1188:

1178:

1154:

1148:

1147:

1119:

1113:

1112:

1094:

1088:

1087:

1059:

1053:

1052:

1040:

1034:

1033:

1005:

999:

998:

978:

972:

971:

951:

945:

944:

924:

918:

917:

901:

895:

894:

866:

860:

859:

819:

813:

812:

794:

788:

787:

775:

769:

768:

742:

733:

727:

726:

718:

712:

711:

687:

681:

680:

652:

643:

642:

614:

605:

604:

596:

590:

589:

561:

555:

554:

522:

516:

509:

503:

496:

490:

489:, 29, 3760–3765.

483:

477:

476:

456:

450:

443:

334:expected utility

296:utility function

265:

263:

262:

257:

239:

237:

236:

231:

219:

217:

216:

211:

198:Andranik Tangian

179:John von Neumann

171:utility function

127:, satisfaction,

21:

1807:

1806:

1802:

1801:

1800:

1798:

1797:

1796:

1787:Decision-making

1762:

1761:

1736:

1731:

1730:

1720:

1718:

1714:Green, Elliot.

1713:

1712:

1708:

1701:

1687:Payne, Jennifer

1684:

1683:

1679:

1672:

1659:

1658:

1651:

1641:

1639:

1635:Steven, Keith.

1634:

1633:

1629:

1619:

1617:

1607:

1606:

1595:

1585:

1583:

1573:

1572:

1565:

1531:

1530:

1519:

1467:

1466:

1462:

1436:

1435:

1431:

1389:

1384:

1383:

1379:

1335:

1334:

1330:

1322:

1320:

1318:

1293:

1292:

1288:

1257:10.1038/nrn3509

1238:

1237:

1233:

1207:

1206:

1202:

1169:(50): 451–478.

1156:

1155:

1151:

1121:

1120:

1116:

1109:

1096:

1095:

1091:

1061:

1060:

1056:

1042:

1041:

1037:

1007:

1006:

1002:

980:

979:

975:

953:

952:

948:

926:

925:

921:

903:

902:

898:

883:10.2307/1907852

868:

867:

863:

821:

820:

816:

809:

796:

795:

791:

777:

776:

772:

740:

735:

734:

730:

720:

719:

715:

689:

688:

684:

654:

653:

646:

616:

615:

608:

598:

597:

593:

563:

562:

558:

524:

523:

519:

510:

506:

497:

493:

484:

480:

458:

457:

453:

444:

440:

435:

397:

381:

373:decision theory

359:

330:

328:Risk preference

242:

241:

222:

221:

202:

201:

117:social sciences

109:

103:

90:decision-making

82:

59:decision theory

35:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

1805:

1803:

1795:

1794:

1789:

1784:

1779:

1774:

1764:

1763:

1760:

1759:

1742:

1735:

1734:External links

1732:

1729:

1728:

1706:

1699:

1677:

1670:

1649:

1627:

1593:

1563:

1544:(2): 239–257.

1517:

1480:(2): 155–172.

1460:

1429:

1406:10.3386/w13976

1377:

1348:(3): 252–262.

1328:

1316:

1286:

1251:(7): 513–518.

1231:

1200:

1149:

1130:(4): 477–504.

1114:

1107:

1089:

1070:(3): 331–335.

1054:

1035:

1000:

973:

962:(2): 476–512.

946:

935:(3): 608–640.

919:

896:

877:(2): 295–300.

861:

834:(4): 379–398.

814:

807:

789:

770:

751:(1): 179–207.

728:

713:

682:

663:(4): 498–511.

644:

625:(2): 139–152.

606:

591:

572:(1): 183–206.

556:

543:10.1086/208905

537:(2): 123–131.

517:

515:, 21, 489–493.

504:

502:, 52, 384–389.

491:

478:

467:(4): 695–729.

451:

437:

436:

434:

431:

430:

429:

424:

419:

414:

408:

403:

396:

393:

380:

377:

358:

355:

329:

326:

325:

324:

321:

318:

255:

252:

249:

229:

209:

105:Main article:

102:

99:

81:

78:

26:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1804:

1793:

1790:

1788:

1785:

1783:

1780:

1778:

1775:

1773:

1770:

1769:

1767:

1756:

1751:

1746:

1743:

1741:

1738:

1737:

1733:

1717:

1710:

1707:

1702:

1700:9781782259602

1696:

1692:

1688:

1681:

1678:

1673:

1671:9780198722861

1667:

1663:

1656:

1654:

1650:

1638:

1631:

1628:

1615:

1611:

1604:

1602:

1600:

1598:

1594:

1581:

1577:

1570:

1568:

1564:

1559:

1555:

1551:

1547:

1543:

1539:

1535:

1528:

1526:

1524:

1522:

1518:

1513:

1509:

1505:

1501:

1496:

1491:

1487:

1483:

1479:

1475:

1471:

1464:

1461:

1456:

1452:

1448:

1444:

1440:

1433:

1430:

1425:

1421:

1416:

1411:

1407:

1403:

1399:

1395:

1388:

1381:

1378:

1373:

1369:

1365:

1361:

1356:

1351:

1347:

1343:

1339:

1332:

1329:

1319:

1313:

1309:

1305:

1301:

1297:

1290:

1287:

1282:

1278:

1274:

1270:

1266:

1262:

1258:

1254:

1250:

1246:

1242:

1235:

1232:

1227:

1223:

1219:

1215:

1211:

1204:

1201:

1196:

1192:

1187:

1182:

1177:

1172:

1168:

1164:

1160:

1153:

1150:

1145:

1141:

1137:

1133:

1129:

1125:

1118:

1115:

1110:

1104:

1100:

1093:

1090:

1085:

1081:

1077:

1073:

1069:

1065:

1058:

1055:

1050:

1046:

1039:

1036:

1031:

1027:

1023:

1019:

1015:

1011:

1004:

1001:

996:

992:

988:

984:

977:

974:

969:

965:

961:

957:

950:

947:

942:

938:

934:

930:

923:

920:

915:

911:

907:

900:

897:

892:

888:

884:

880:

876:

872:

865:

862:

857:

853:

849:

845:

841:

837:

833:

829:

825:

818:

815:

810:

808:9780128120231

804:

800:

793:

790:

785:

781:

774:

771:

766:

762:

758:

754:

750:

746:

739:

732:

729:

724:

717:

714:

709:

705:

701:

697:

693:

686:

683:

678:

674:

670:

666:

662:

658:

651:

649:

645:

640:

636:

632:

628:

624:

620:

613:

611:

607:

602:

595:

592:

587:

583:

579:

575:

571:

567:

560:

557:

552:

548:

544:

540:

536:

532:

528:

521:

518:

514:

508:

505:

501:

495:

492:

488:

482:

479:

474:

470:

466:

462:

455:

452:

448:

442:

439:

432:

428:

425:

423:

420:

418:

415:

412:

409:

407:

404:

402:

399:

398:

394:

392:

390:

386:

378:

376:

374:

369:

368:

363:

356:

354:

351:

348:

344:

340:

337:

335:

327:

322:

319:

316:

315:

314:

311:

310:commodities.

307:

305:

304:loss aversion

301:

297:

293:

289:

285:

280:

276:

272:

267:

253:

250:

247:

227:

207:

199:

195:

194:Gérard Debreu

190:

188:

184:

180:

176:

172:

163:

159:

157:

153:

147:

145:

141:

138:

134:

130:

129:gratification

126:

122:

118:

114:

108:

100:

98:

96:

91:

87:

79:

77:

75:

70:

68:

64:

60:

56:

52:

48:

44:

40:

33:

19:

1719:. Retrieved

1709:

1690:

1680:

1661:

1640:. Retrieved

1630:

1618:. Retrieved

1613:

1584:. Retrieved

1579:

1541:

1537:

1477:

1473:

1463:

1446:

1442:

1432:

1397:

1393:

1380:

1345:

1341:

1331:

1321:, retrieved

1299:

1289:

1248:

1244:

1234:

1217:

1213:

1203:

1186:10419/253806

1166:

1162:

1152:

1127:

1123:

1117:

1098:

1092:

1067:

1063:

1057:

1048:

1044:

1038:

1016:(1): 14–28.

1013:

1009:

1003:

989:(1): 73–92.

986:

982:

976:

959:

955:

949:

932:

928:

922:

905:

899:

874:

871:Econometrica

870:

864:

831:

827:

817:

798:

792:

783:

779:

773:

748:

744:

731:

722:

716:

699:

695:

685:

660:

656:

622:

618:

600:

594:

569:

565:

559:

534:

530:

520:

512:

507:

499:

494:

486:

481:

464:

460:

454:

446:

441:

382:

365:

361:

360:

352:

349:

345:

341:

338:

331:

312:

308:

268:

191:

168:

152:transitivity

148:

137:World War II

120:

110:

83:

71:

55:alternatives

50:

36:

1721:December 1,

1582:. Routledge

1220:(4): 7–43.

362:Preferences

298:. Economic

1766:Categories

1642:October 1,

1323:2023-04-23

433:References

401:Motivation

385:Insolvency

379:Insolvency

292:Heuristics

284:heuristics

121:preference

115:and other

86:psychology

80:Psychology

74:insolvency

51:preference

47:philosophy

39:psychology

1782:Free will

1558:155414997

1504:0895-3309

1449:: 43–51.

1364:1930-2975

1265:1471-003X

1226:2083-1277

1195:158379317

1144:146886098

1084:154665809

1030:143743641

856:244976714

848:0021-5368

702:: 61–86.

586:158564367

551:0093-5301

251:−

125:happiness

113:economics

101:Economics

43:economics

1689:(2015).

1610:"Desire"

1576:"Desire"

1512:30203934

1424:24761048

1281:12544303

1273:23756633

745:Synthese

677:29003374

639:15220288

395:See also

196:enabled

18:Penchant

1777:Utility

1415:3993927

1372:2468108

891:1907852

765:6430197

367:desires

133:utility

95:choices

67:desires

1697:

1668:

1556:

1510:

1502:

1422:

1412:

1370:

1362:

1314:

1279:

1271:

1263:

1224:

1193:

1142:

1105:

1082:

1028:

889:

854:

846:

805:

763:

675:

637:

584:

549:

422:Choice

300:biases

288:biases

187:axioms

1747:

1620:3 May

1586:4 May

1554:S2CID

1390:(PDF)

1368:S2CID

1277:S2CID

1191:S2CID

1140:S2CID

1080:S2CID

1026:S2CID

887:JSTOR

852:S2CID

761:S2CID

741:(PDF)

673:S2CID

635:S2CID

582:S2CID

1723:2022

1695:ISBN

1666:ISBN

1644:2018

1622:2021

1588:2021

1508:PMID

1500:ISSN

1420:PMID

1360:ISSN

1312:ISBN

1269:PMID

1261:ISSN

1222:ISSN

1103:ISBN

1051:(1).

844:ISSN

803:ISBN

547:ISSN

364:and

286:and

181:and

154:and

45:and

1755:DOC

1546:doi

1490:hdl

1482:doi

1451:doi

1410:PMC

1402:doi

1350:doi

1304:doi

1253:doi

1181:hdl

1171:doi

1132:doi

1072:doi

1018:doi

991:doi

964:doi

960:159

937:doi

933:141

910:doi

879:doi

836:doi

753:doi

749:187

704:doi

665:doi

627:doi

574:doi

539:doi

469:doi

383:In

111:In

84:In

72:In

37:In

1768::

1652:^

1612:.

1596:^

1578:.

1566:^

1552:.

1542:31

1540:.

1536:.

1520:^

1506:.

1498:.

1488:.

1478:32

1476:.

1472:.

1447:87

1445:.

1441:.

1418:.

1408:.

1398:92

1396:.

1392:.

1366:.

1358:.

1344:.

1340:.

1310:,

1298:,

1275:.

1267:.

1259:.

1249:14

1247:.

1243:.

1216:.

1212:.

1189:.

1179:.

1167:25

1165:.

1161:.

1138:.

1128:22

1126:.

1078:.

1068:40

1066:.

1049:17

1047:.

1024:.

1014:20

1012:.

987:38

985:.

958:.

931:.

885:.

875:20

873:.

850:.

842:.

832:65

830:.

826:.

784:37

782:.

759:.

747:.

743:.

700:56

698:.

694:.

671:.

661:18

659:.

647:^

633:.

623:25

621:.

609:^

580:.

570:26

568:.

545:.

533:.

529:.

465:44

463:.

290:.

119:,

49:,

41:,

1725:.

1703:.

1674:.

1646:.

1624:.

1590:.

1560:.

1548::

1514:.

1492::

1484::

1457:.

1453::

1426:.

1404::

1374:.

1352::

1346:6

1306::

1283:.

1255::

1228:.

1218:5

1197:.

1183::

1173::

1146:.

1134::

1111:.

1086:.

1074::

1032:.

1020::

997:.

993::

970:.

966::

943:.

939::

916:.

912::

893:.

881::

858:.

838::

811:.

786:.

767:.

755::

710:.

706::

679:.

667::

641:.

629::

588:.

576::

553:.

541::

535:9

475:.

471::

254:1

248:n

228:n

208:n

34:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.