212:(§18), Leibniz posits quantitative differences in perfection between monads which leads to a hierarchical ordering. The basic order is three-tiered: (1) entelechies or created monads (§48), (2) souls or entelechies with perception and memory (§19), and (3) spirits or rational souls (§82). Whatever is said about the lower ones (entelechies) is valid for the higher (souls and spirits) but not vice versa. As none of them is without a body (§72), there is a corresponding hierarchy of (1) living beings and animals (2), the latter being either (2) non-reasonable or (3) reasonable. The degree of perfection in each case corresponds to cognitive abilities and only spirits or reasonable animals are able to grasp the ideas of both the world and its creator. Some monads have power over others because they can perceive with greater clarity, but primarily, one monad is said to dominate another if it contains the reasons for the actions of other(s). Leibniz believed that any body, such as the body of an animal or man, has one dominant monad which controls the others within it. This dominant monad is often referred to as the soul.

235:

each organ of an animal, each drop of its bodily fluids is also a similar garden or a similar pond". There are no interactions between different monads nor between entelechies and their bodies but everything is regulated by the pre-established harmony (§§78–9). Much like how one clock may be in synchronicity with another, but the first clock is not caused by the second (or vice versa), rather they are only keeping the same time because the last person to wind them set them to the same time. So it is with monads; they may seem to cause each other, but rather they are, in a sense, "wound" by God's pre-established harmony, and thus appear to be in synchronicity. Leibniz concludes that "if we could understand the order of the universe well enough, we would find that it surpasses all the wishes of the wisest people, and that it is impossible to make it better than it is—not merely in respect of the whole in general, but also in respect of ourselves in particular" (§90).

251:

because a monad is a “simple substance” and God is simplest of all substances, He cannot be broken down any further. This means that all monads perceive “with varying degrees of perception, except for God, who perceives all monads with utter clarity”. This superior perception of God then would apply in much the same way that he says a dominant monad controls our soul, all other monads associated with it would, essentially, shade themselves towards Him. With all monads being created by the ultimate monad and shading themselves in the image of this ultimate monad, Leibniz argues that it would be impossible to conceive of a more perfect world because all things in the world are created by and imitating the best possible monad.

239:

likewise substance itself. The only things that could be called real were utterly simple beings of psychic activity "endowed with perception and appetite." The other objects, which we call matter, are merely phenomena of these simple perceivers. "Leibniz says, 'I don't really eliminate body, but reduce it to what it is. For I show that corporeal mass , which is thought to have something over and above simple substances, is not a substance, but a phenomenon resulting from simple substances, which alone have unity and absolute reality.' (G II 275/AG 181)" Leibniz's philosophy is sometimes called "'

945:

625:

74:

22:

234:

Composite substances or matter are "actually sub-divided without end" and have the properties of their infinitesimal parts (§65). A notorious passage (§67) explains that "each portion of matter can be conceived as like a garden full of plants, or like a pond full of fish. But each branch of a plant,

250:

Leibniz uses his theory of Monads to support his argument that we live in the best of all possible worlds. He uses his basis of perception but not interaction among monads to explain that all monads must draw their essence from one ultimate monad. He then claims that this ultimate monad would be God

218:

God is also said to be a simple substance (§47) but it is the only one necessary (§§38–9) and without a body attached (§72). Monads perceive others "with varying degrees of clarity, except for God, who perceives all monads with utter clarity". God could take any and all perspectives, knowing of both

238:

In his day, atoms were proposed to be the smallest division of matter. Within

Leibniz's theory, however, substances are not technically real, so monads are not the smallest part of matter, rather they are the only things which are, in fact, real. To Leibniz, space and time were an illusion, and

243:

idealism' because these substances are psychic rather than material". That is to say, they are mind-like substances, not possessing spatial reality. "In other words, in the

Leibnizian monadology, simple substances are mind-like entities that do not, strictly speaking, exist in space but that

628:

392:

Translated by

Frederic Henry Hedge. "Leibniz's vestige view of God's creative act is employed to support his view of substance as an inherently active being possessed of its own dynamic force" in David Scott, "Leibniz model of creation and his doctrine of substance",

227:

of the

Divinity" (§47). Any perfection comes from being created while imperfection is a limitation of nature (§42). The monads are unaffected by each other, but each have a unique way of expressing themselves in the universe, in accordance with God's infinite will.

151:, the word and the idea, belongs to the Western philosophical tradition and has been used by various authors. Leibniz, who was exceptionally well-read, could not have ignored this, but he did not use it himself until mid-1696 when he was sending for print his

126:. There are three original manuscripts of the text: the first written by Leibniz and glossed with corrections and two further emended copies with some corrections appearing in one but not the other. Leibniz himself inserted references to the paragraphs of his

223:. As well as that God in all his power would know the universe from each of the infinite perspectives at the same time, and so his perspectives—his thoughts—"simply are monads". Creation is a permanent state, thus " are generated, so to speak, by continual

244:

represent the universe from a unique perspective." It is the harmony between the perceptions of the monads which creates what we call substances, but that does not mean the substances are real in and of themselves.

208:' and described as 'a simple substance' (§§1, 19). When Leibniz says that monads are 'simple,' he means that "which is one, has no parts and is therefore indivisible". Relying on the Greek etymology of the word

163:. Leibniz surmised that there are indefinitely many substances individually 'programmed' to act in a predetermined way, each substance being coordinated with all the others. This is the

699:

639:

643:

155:. Apparently he found with it a convenient way to expound his own philosophy as it was elaborated in this period. What he proposed can be seen as a modification of

972:

736:

692:

85:

from 1712 to

September 1714, Leibniz wrote two short texts in French which were meant as concise expositions of his philosophy. After his death,

617:

599:

577:

370:

Audi Robert, ed. "Leibniz, Gottfried

Wilhelm." The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press (1999): 193.

359:

On pourrait donner le nom d'entéléchies à toutes les substances simples ou

Monades créées, car elles ont en elles une certaine perfection

948:

685:

929:

900:

841:

591:

569:

967:

824:

94:

749:

731:

977:

770:

220:

708:

260:

890:

863:

814:

760:

726:

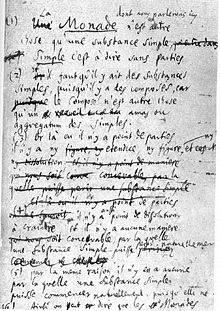

164:

819:

765:

614:, English translation, links, scalable text and printable version. Downloadable as pdf, doc or djvu files.

97:

and collaborators published translations in German and Latin of the second text which came to be known as

742:

669:

795:

880:

808:

168:

132:("Theodicy", i.e. a justification of God), sending the interested reader there for more details.

61:

398:

200:

As far as

Leibniz allows just one type of element in the building of the universe his system is

851:

780:

595:

587:

573:

565:

44:

447:

Pestana, Mark. "Gottfried

Wilhelm Leibniz." World Philosophers & Their Works (2000): 1–4.

435:

422:

380:

801:

790:

557:

56:

118:

90:

36:

910:

469:

Burnham, Douglas. "Gottfried

Leibniz: Metaphysics." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

456:

Burnham, Douglas. "Gottfried Leibniz: Metaphysics." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

408:

Burnham, Douglas. "Gottfried Leibniz: Metaphysics." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

345:

Burnham, Douglas. "Gottfried Leibniz: Metaphysics." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

128:

830:

755:

484:

316:

187:

begins with a description of monads (proceeding from simple to complicated instances),

961:

785:

775:

523:

504:

315:

There is no indication that Leibniz has 'borrowed' it from a particular author, e.g.

271:

171:, but at the cost of declaring any interaction between substances a mere appearance.

156:

73:

21:

224:

657:(1981), with facsimile of Leibniz's manuscript, and introduction by Gustavo Bueno

846:

663:

611:

240:

52:

160:

48:

677:

205:

857:

836:

634:

320:

654:

289:

Lamarra A., Contexte Génétique et Première Réception de la Monadologie,

470:

457:

409:

346:

147:

201:

82:

434:

Look, Brandon C. "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz." Stanford University,

421:

Look, Brandon C. "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz." Stanford University,

379:

Look, Brandon C. "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz." Stanford University,

649:

72:

20:

681:

204:. The unique element has been 'given the general name monad or

51:. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a

662:

584:

Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Leibniz and the Monadology

436:

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/leibniz

423:

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/leibniz

381:

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/leibniz

650:

A version of this work, lightly edited for easier reading

334:

Leibniz's "New System" and associated contemporary texts

105:

they had assumed that it was the French original of the

87:

Principes de la nature et de la grâce fondés en raison

872:

715:

101:. Without having seen the Dutch publication of the

522:

503:

306:, edition établie par E. Boutroux, Paris LGF 1991

190:then it turns to their principle or creator and

109:which in fact remained unpublished until 1840.

179:The rhetorical strategy adopted by Leibniz in

693:

8:

193:finishes by using both to explain the world.

112:The German translation appeared in 1720 as

77:The first manuscript page of the Monadology

700:

686:

678:

93:, appeared in French in the Netherlands.

564:, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991,

282:

323:, to mention just two popular sources

7:

673:. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

489:Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

471:http://www.iep.utm.edu/leib-met/#H8

458:http://www.iep.utm.edu/leib-met/#H8

410:http://www.iep.utm.edu/leib-met/#H8

347:http://www.iep.utm.edu/leib-met/#H8

973:Works by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

47:'s best known works of his later

14:

901:New Essays on Human Understanding

842:Transcendental law of homogeneity

661:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913).

655:French, Latin and Spanish edition

944:

943:

646:(1999), by George MacDonald Ross

623:

89:, which was intended for prince

540:Antognazza, Maria Rosa (2016).

183:is fairly obvious as the text

114:Lehrsätze über die Monadologie

1:

930:Leibniz–Clarke correspondence

332:Woolhouse R. and Francks R.,

122:printed the Latin version as

16:Philosophical work by Leibniz

521:Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm.

502:Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm.

336:, Cambridge Univ. Press 1997

750:Characteristica universalis

732:Best of all possible worlds

633:public domain audiobook at

485:"Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz"

116:and the following year the

994:

771:Identity of indiscernibles

562:G. W. Leibniz's Monadology

544:. Oxford University Press.

221:potentiality and actuality

941:

709:Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

891:Discourse on Metaphysics

159:developed by latter-day

81:During his last stay in

864:Well-founded phenomenon

815:Pre-established harmony

727:Alternating series test

165:pre-established harmony

968:1714 non-fiction books

620:(1898) by Robert Latta

491:. Stanford University.

124:Principia philosophiae

78:

40:

26:

743:Calculus ratiocinator

670:Catholic Encyclopedia

76:

24:

881:De Arte Combinatoria

809:Mathesis universalis

737:Calculus controversy

586:, Routledge (2000),

640:English translation

618:English translation

558:Nicholas Rescher N.

361:(ἔχουσι τὸ ἐντελές)

796:Leibniz's notation

293:128 (2007) 311–323

79:

43:, 1714) is one of

27:

978:Metaphysics books

955:

954:

933:(1715–1716)

852:Universal science

825:Sufficient reason

781:Law of continuity

600:978-0-415-17113-7

578:978-0-8229-5449-1

483:Look, Brandon C.

291:Revue de Synthese

169:mind-body problem

167:which solved the

45:Gottfried Leibniz

985:

947:

946:

934:

926:

916:

906:

896:

886:

802:Lingua generalis

702:

695:

688:

679:

674:

666:

627:

626:

546:

545:

537:

531:

530:

528:

518:

512:

511:

509:

499:

493:

492:

480:

474:

467:

461:

454:

448:

445:

439:

432:

426:

419:

413:

406:

400:

390:

384:

377:

371:

368:

362:

356:

350:

343:

337:

330:

324:

313:

307:

300:

294:

287:

993:

992:

988:

987:

986:

984:

983:

982:

958:

957:

956:

951:

937:

932:

924:

914:

904:

894:

884:

868:

720:

718:

717:Mathematics and

711:

706:

660:

624:

608:

554:

549:

539:

538:

534:

520:

519:

515:

501:

500:

496:

482:

481:

477:

468:

464:

455:

451:

446:

442:

433:

429:

420:

416:

407:

403:

391:

387:

378:

374:

369:

365:

357:

353:

344:

340:

331:

327:

314:

310:

301:

297:

288:

284:

280:

257:

177:

143:

138:

119:Acta Eruditorum

95:Christian Wolff

91:Eugene of Savoy

71:

17:

12:

11:

5:

991:

989:

981:

980:

975:

970:

960:

959:

953:

952:

942:

939:

938:

936:

935:

927:

917:

907:

897:

887:

876:

874:

870:

869:

867:

866:

861:

854:

849:

844:

839:

834:

831:Salva veritate

827:

822:

817:

812:

805:

798:

793:

788:

783:

778:

773:

768:

763:

758:

756:Compossibility

753:

746:

739:

734:

729:

723:

721:

716:

713:

712:

707:

705:

704:

697:

690:

682:

676:

675:

658:

652:

647:

637:

621:

615:

612:The Monadology

607:

606:External links

604:

603:

602:

580:

553:

550:

548:

547:

532:

513:

494:

475:

462:

449:

440:

427:

414:

401:

385:

372:

363:

351:

338:

325:

317:Giordano Bruno

308:

304:La Monadologie

302:Leibniz G.W.,

295:

281:

279:

276:

275:

274:

269:

256:

253:

195:

194:

191:

188:

181:The Monadology

176:

173:

142:

139:

137:

134:

99:The Monadology

70:

67:

41:La Monadologie

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

990:

979:

976:

974:

971:

969:

966:

965:

963:

950:

940:

931:

928:

923:

922:

918:

913:

912:

908:

903:

902:

898:

893:

892:

888:

883:

882:

878:

877:

875:

871:

865:

862:

860:

859:

855:

853:

850:

848:

845:

843:

840:

838:

835:

833:

832:

828:

826:

823:

821:

818:

816:

813:

811:

810:

806:

804:

803:

799:

797:

794:

792:

791:Leibniz's gap

789:

787:

786:Leibniz wheel

784:

782:

779:

777:

776:Individuation

774:

772:

769:

767:

764:

762:

759:

757:

754:

752:

751:

747:

745:

744:

740:

738:

735:

733:

730:

728:

725:

724:

722:

714:

710:

703:

698:

696:

691:

689:

684:

683:

680:

672:

671:

665:

664:"Monad"

659:

656:

653:

651:

648:

645:

641:

638:

636:

632:

631:

622:

619:

616:

613:

610:

609:

605:

601:

597:

593:

592:0-415-17113-X

589:

585:

581:

579:

575:

571:

570:0-8229-5449-4

567:

563:

559:

556:

555:

551:

543:

536:

533:

527:

526:

517:

514:

508:

507:

498:

495:

490:

486:

479:

476:

472:

466:

463:

459:

453:

450:

444:

441:

437:

431:

428:

424:

418:

415:

411:

405:

402:

399:

396:

389:

386:

382:

376:

373:

367:

364:

360:

355:

352:

348:

342:

339:

335:

329:

326:

322:

318:

312:

309:

305:

299:

296:

292:

286:

283:

277:

273:

272:Perspectivism

270:

268:

267:

263:

259:

258:

254:

252:

249:

245:

242:

236:

233:

229:

226:

222:

217:

213:

211:

207:

203:

199:

192:

189:

186:

185:

184:

182:

174:

172:

170:

166:

162:

158:

157:occasionalism

154:

150:

149:

140:

135:

133:

131:

130:

125:

121:

120:

115:

110:

108:

104:

100:

96:

92:

88:

84:

75:

68:

66:

64:

63:

58:

54:

50:

46:

42:

38:

34:

33:

23:

19:

920:

919:

909:

899:

889:

879:

856:

829:

807:

800:

748:

741:

668:

629:

583:

561:

541:

535:

524:

516:

505:

497:

488:

478:

465:

452:

443:

430:

417:

404:

394:

388:

375:

366:

358:

354:

341:

333:

328:

311:

303:

298:

290:

285:

266:a posteriori

265:

261:

247:

246:

237:

231:

230:

225:fulgurations

215:

214:

209:

197:

196:

180:

178:

152:

146:

144:

127:

123:

117:

113:

111:

106:

102:

98:

86:

80:

60:

31:

30:

28:

18:

847:Rationalism

582:Savile A.,

136:Metaphysics

107:Monadology,

53:metaphysics

962:Categories

921:Monadology

761:Difference

719:philosophy

644:commentary

630:Monadology

552:References

525:Monadology

506:Monadology

241:panpsychic

210:entelechie

161:Cartesians

153:New System

57:substances

55:of simple

49:philosophy

32:Monadology

25:Monadology

911:Théodicée

820:Plenitude

397:3 (1998)

206:entelechy

129:Théodicée

103:Principes

949:Category

858:Vis viva

837:Theodicy

766:Dynamism

635:LibriVox

321:John Dee

262:A priori

255:See also

202:monistic

542:Leibniz

175:Summary

141:Context

925:(1714)

915:(1710)

905:(1704)

895:(1686)

885:(1666)

598:

590:

576:

568:

395:Animus

83:Vienna

62:monads

37:French

873:Works

278:Notes

232:(III)

148:monad

59:, or

642:and

596:ISBN

588:ISBN

574:ISBN

566:ISBN

264:and

248:(IV)

216:(II)

145:The

69:Text

29:The

594:,

319:or

198:(I)

964::

667:.

572:,

560:,

487:.

65:.

39::

701:e

694:t

687:v

529:.

510:.

473:.

460:.

438:.

425:.

412:.

383:.

349:.

35:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.