520:

516:

chariots remained in strict formation there would be a good opportunity to encircle the enemy. During this period of chariot warfare, the use of orderly team-based combat to some extent determined the difference between victory and defeat, otherwise fighting would have to stop in order to consolidate the formation. In this type operation unified command was important. Senior officers would use drums and flags to command the army's advance and retreat, speed and to make formation adjustments. However such operations were inherently very slow-paced and the speed of engagement thus hampered. Furthermore, the infantry had to remain in line which was not conducive to long-distance pursuits of retreating enemies.

320:

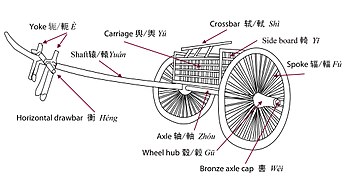

359:(771–476 BCE) improvements had been made to the chariot's design and construction. The angle of the curved draw pole had increased raising the end of the pole. This reduced the amount of effort required by the horse pulling the chariot and increased its speed. The width of the carriage body had also increased to around 1.5 m allowing soldiers greater freedom of movement. Key components such as the pole, hubcap and yoke were reinforced with decorated copper castings, increasing the chariot's stability and durability. These chariots were variously referred to as "gold chariots" (金車), "attack chariots" (攻車) or "weapons chariots" (戎車).

489:

481:

352:

wooden yokes attached, to which the horses would be harnessed. Wooden wheels with a diameter of between approximately 1.2 – 1.4 m were mounted on a three-meter-long (9.8 ft) axle and secured at each end with a bronze hubcap. Wheels of the Shang period usually had 18 spokes, but those of the Zhou period numbered from 18 to 26. Chariot wheels of the Spring and Autumn period (8th–7th century BCE) had between 25 and 28 spokes. The carriage body was around one meter long and 0.8 meters wide with wooden walls and an opening at the back to provide access for soldiers.

336:

219:

470:

50:

372:

200:

461:军). In the Spring and Autumn period the chariot became the main weapon of war. Along with each state's increase in military manpower, their proportion of chariots to overall army numbers also fell with the number of men allocated to each chariot increasing to seventy. This alteration fundamentally changed the fundamentals of warfare.

554:

around all four sides thereby increasing the vehicle's flexibility. Formations no longer involved a single line of chariots; instead they were spread out which brought the advantage of depth. In this way the chariot's movement was no longer impeded so it could counter enemy attacks as well as provide a fast pursuit vehicle.

512:. These tactics required fighting in tight formation with good military discipline and control. When the spring and autumn period began, more attention was paid to troop formations according to the type of battle. Chariot units were trained to ensure co-ordination with the rest of the army during a military campaign.

262:(471–221 BCE) when increasing use of the crossbow, massed infantry, the adoption of standard cavalry units and the adaptation of nomadic cavalry (mounted archery) took over. Chariots continued to serve as command posts for officers during the Qin and Han dynasties while armored chariots were also used by the

695:

Recent publications of archeological discoveries throughout Soviet

Central Asia, however, now allow the previous void between China and the Near East to be filled both spatially and temporally, leaving no doubt that the chariot did indeed enter China from the northwest at about 1200 B.C. (...) From

351:

Ancient

Chinese chariots were typically two wheeled vehicles drawn by two or four horses with a single draught pole measuring around 3 m long that was originally straight but later evolved into two curved shafts. At the front end of the pole there was a horizontal draw-bar about one meter long with

537:

in 1046 BCE. As the Zhou army moved forward, the infantry and chariots were commanded to stop and regroup after every six or seven steps to maintain formation. The Shang army, despite its superior numbers, was largely composed of demoralized and forcibly conscripted troops. As a result, the troops

503:

Chariot-based combat usually took place in wide-open spaces. When the two sides were within range, they would first exchange arrow or crossbow fire, hoping that through superior numbers they would cause disorder and confusion in the enemy ranks. As the two opponents closed on each other they would

507:

Only about three meters wide, with infantry riding on both sides, the chariot was highly inflexible as a fighting machine and difficult to turn around. Coupled with this were restrictions on the use of weapons with opponents seizing the momentary opportunity for victory or trapping their opponent

553:

the disorganized nature of the Chu army's chariots and infantry led to its defeat. Both troop formations and the flexibility of the chariot subsequently underwent major developments with infantry placing a much larger role in combat. Troops were no longer deployed forward of chariots but instead

515:

During the

Western Zhou Era, chariots were deployed on wide-open plains abreast of each other in a single line. The accompanying infantry would then be deployed forward of the chariot, a broad formation that denied the enemy the opportunity for pincer attacks. When the two sides clashed, if the

499:

In ancient China the chariot was used in a primary role from the time of the Shang dynasty until the early years of the Han dynasty (c. 1200–200 BCE) when it was replaced by cavalry and fell back into a secondary support role. For a millennium or more, every chariot borne soldier had used the

305:

dynasties (221 BCE – 220 CE) the chariot was replaced by cavalry and infantry, and the single-pole chariot became less important. At this time the double shaft chariot developed as a transport vehicle which was light and easy to handle. During the

Eastern Han (25–220 CE) and later during the

1236:

310:

period (220–280 CE), the double shaft chariot was the predominant form. This change is seen in innumerable Han dynasty stone carvings and in many ceramic tomb models. Over time, as society evolved, the early chariot of the Pre-Qin period gradually disappeared.

362:

The

Chinese war chariot, like the other war chariots of Eurasia, derived its characteristic ability to perform at high speed by a combination of a light design, together with a propulsion system using horses, which were the fastest draft animals available.

408:

All chariot commanders carried a bronze dagger for protection in the case of the chariot becoming unserviceable or an enemy jumping on board the chariot. Soldiers aboard wore leather or occasionally copper armour and carried a shield or

379:

Usually a chariot carried three armored warriors with different tasks: one, known as the charioteer (御者) was responsible for driving, a second, the archer (射) (or sometimes multiple archers (多射)) tasked with long range shooting. The

641:

have illuminated the key role of the

Mongolia plateau as a major region of origin for chariot and horse use in East Asia (and their associated weapons and tools), and also the likely source for the chariots and horses employed at

429:) for long distance attacks. Chariot horses also began to wear armor during the Spring and Autumn period to protect against injury. When the chariot was not engaged in a military campaign, it was used as a transport vehicle.

1185:

1178:

441:(徒卒) to co-operate in battle. During the Western Zhou era, ten infantry were usually allocated to each chariot with five of them riding on the chariot, each of which was called a squadron (

437:

The chariot was a large military vehicle that through its lack of flexibility was not effective as a single combat unit. Usually its commander would be allocated a number of infantrymen or

696:

this we might suggest an upper limit for artifactual evidence of the chariot in China of about 1200 B.C., which corresponds to the last part of King Wu Ding's reign (c. 1200-1180 B.C.).

1256:

1241:

1171:

504:

stay about four meters apart to avoid the three-meter-long (9.8 ft) dagger-axes of their opponents. Only when two chariots came closer than this would an actual fight occur.

237:, and say they were used at the Battle of Gan (甘之戰) in the 21st century BCE. However archeological evidence shows that small scale use of the chariot began around 1200 BCE in the

391:(戈), a weapon with a roughly three-meter shaft. At the end of the double-headed device there was a sharp dagger on one side and an axe head on the other. This was carried by the

1079:, p. 53 (note: although Beckwith is making a general statement about war chariots in general, this also is explicitly tied to the Chinese war chariot elsewhere in the text)

519:

974:

384:(戎右), whose role was short range defense, made up the third member of the crew. Weapons carried on the chariot consisted of close-combat and long range weapons.

1271:

1419:

319:

1047:

1231:

1464:

1195:

1132:

954:

865:

838:

1544:

1266:

1251:

1549:

1246:

1153:

1529:

175:

also allowed military commanders a mobile platform from which to control troops while providing archers and soldiers armed with

30:

1220:

344:

136:

68:

1211:

1089:

144:

1286:

1281:

1276:

1216:

568:

488:

286:'s army of 80,000 cavalry. Wei Qing ordered his troops to arrange heavy-armored chariots in a ring formation, creating

1539:

1504:

1226:

1002:

533:

A typical example of the importance of disciplined forces occurred during the Zhou overthrow of Shang at the decisive

1359:

480:

210:

ruins. Shang chariots were introduced around 1200 BCE through the northern steppes, probably from the area of the

395:

and could be either swung or thrust like a spear at the enemy. By the time of the Spring and Autumn period the

356:

180:

1407:

1120:

246:

1296:

573:

167:'war vehicle') was used as an attack and pursuit vehicle on the open fields and plains of ancient

1374:

1316:

1309:

1304:

1203:

881:

Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988). "Historical

Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China".

259:

712:

603:"Chariotry and Prone Burials: Reassessing Late Shang China's Relationship with Its Northern Neighbours"

1394:

1364:

1055:

855:

271:

550:

335:

242:

211:

787:

293:

With changes in the nature of warfare, as well as the increasing availability of larger breeds of

241:

period. They were probably introduced through the northern steppes, probably from the area of the

218:

1554:

1424:

1369:

994:

916:

898:

798:

686:

624:

1163:

830:

824:

1534:

1149:

1128:

950:

861:

834:

678:

542:

986:

890:

670:

614:

469:

405:(戟) which had a spear blade at the end of the shaft in addition to the axe head and dagger.

99:

49:

255:

depict a chariot-like two wheeled vehicle with a single pole for the attachment of horses.

1354:

527:

509:

275:

29:

This article is about the ancient vehicle. For the traditional

Chinese constellation, see

1125:

Empires of the Silk Road: A History of

Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present

371:

199:

1483:

1458:

1344:

1143:

1050:[Fierce and effective weapons of Ancient China: Chariots and Chariot Warfare].

534:

307:

222:

1523:

1489:

1477:

1349:

998:

917:"Excavation of Zhou Dynasty Chariot Tombs Reveals More About Ancient Chinese Society"

746:

628:

602:

541:

As the Spring and Autumn period dawned, chariots remained the key to victory. At the

328:

204:

1412:

1261:

493:

414:

400:

106:

258:

Chariots reached their apogee and remained a powerful weapon until the end of the

1436:

638:

546:

523:

474:

387:

The most important close-combat weapon aboard the chariot was the dagger-axe or

340:

324:

302:

298:

263:

230:

188:

1093:

619:

17:

1451:

1429:

1402:

990:

634:

287:

238:

176:

682:

1496:

1384:

764:

741:

857:

Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art

1442:

422:

413:(盾) made from leather or bronze. The chariot's archer was armed either a

279:

234:

1470:

1379:

902:

737:

690:

659:"Historical Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China"

658:

563:

267:

184:

172:

55:

793:

769:

283:

152:

894:

674:

823:

Ebrey, Patricia

Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006).

518:

487:

479:

468:

370:

334:

318:

294:

229:

Traditional sources attribute the invention of the chariot to the

217:

207:

198:

168:

179:

increased mobility. They reached a peak of importance during the

1167:

713:"Wheeled Vehicles in the Chinese Bronze Age (c. 2000-741 B.C.)"

282:'s army, setting off from Dingxiang, encountered the Xiongnu

500:

particular combat tactics that use of the vehicle required.

797:, vol. 1, Chariot Section (車部). quote: "世本奚仲作車宋忠曰夏禹時人也".

111:

826:

East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History

1393:

1332:

1325:

1295:

1202:

105:

98:

93:

81:

67:

38:

947:Imperial Chinese military history: 8000BC-1912AD

923:. Beijing: People's Daily Online. 16 March 2002

801:scanned and transcribed by Chinese Text Project

538:failed to stay in formation and were defeated.

457:师) while five divisions were known as an army (

399:had largely been superseded by the halberd or

1179:

949:. Lincoln: iUniverse, Inc. pp. 154–155.

940:

938:

250:

73:

8:

1148:(2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

975:"Chariot and horse burials in ancient China"

829:. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p.

162:

1329:

1186:

1172:

1164:

1054:(in Chinese). 17 July 2008. Archived from

711:Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (February 2000).

90:

1127:. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

1042:

1040:

1038:

1036:

1034:

1032:

618:

1076:

968:

966:

810:

633:These different monuments, petroglyphs,

590:

1090:"Weapons of the Warring States Period"

1023:

765:"Chapter on Inventions (作篇) - Xia (夏)"

706:

704:

473:Miniature bronze chariot with an axe,

35:

652:

650:

7:

596:

594:

860:. Barnes & Noble. p. 227.

883:Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

663:Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

25:

1257:Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms

1145:A History of Chinese Civilization

545:in 575 BCE between the States of

183:, but were largely superseded by

973:Lu Liancheng (1 December 1993).

48:

657:Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988).

465:Combat and tactical disposition

31:Chariot (Chinese constellation)

323:Powerful landlord in chariot.

157:

148:

140:

112:

74:

1:

1013:– via The Free Library.

601:Rawson, Jessica (June 2020).

445:隊). Five squadrons made up a

1092:(in Chinese). Archived from

569:Horses in East Asian warfare

484:Scythed Chinese chariot axle

375:Scythed Chinese chariot axle

1545:Horse history and evolution

1505:Self Strengthening Movement

945:Whiting, Marvin C. (2002).

607:Journal of World Prehistory

1571:

1550:Military vehicles of China

1237:Jin & Sixteen Kingdoms

620:10.1007/s10963-020-09142-4

28:

991:10.1017/S0003598X0006381X

251:

123:

89:

47:

43:

39:Chariots in ancient China

1196:Chinese military history

1142:Gernet, Jacques (1996).

1121:Beckwith, Christopher I.

357:Spring and Autumn period

355:With the arrival of the

247:oracle bone inscriptions

181:Spring and Autumn period

69:Traditional Chinese

1530:Animal-powered vehicles

1242:Northern & Southern

133:ancient Chinese chariot

1465:Ming gunpowder weapons

1420:Song gunpowder weapons

574:South-pointing chariot

530:

496:

485:

477:

433:Operational deployment

376:

348:

343:chariot, from Tomb of

332:

274:, specifically at the

226:

215:

171:from around 1200 BCE.

1305:Ming treasure voyages

1194:Ancient and dynastic

1048:"中国古代战争的凶猛利器:古代战车及车战"

522:

491:

483:

472:

374:

338:

322:

270:Confederation in the

260:Warring States period

221:

202:

1484:Breechloading musket

854:Woolf, Greg (2007).

720:Sino-Platonic Papers

339:Model recreation of

453:formed a division (

278:in 119 CE. General

243:Deer stones culture

212:Deer stones culture

137:traditional Chinese

1540:Chinese inventions

1425:Thunder crash bomb

1370:Repeating crossbow

1005:on 21 October 2012

531:

497:

486:

478:

377:

349:

333:

227:

225:chariot burial pit

216:

145:simplified Chinese

1517:

1516:

1513:

1512:

1134:978-0-691-13589-2

956:978-0-595-22134-9

867:978-1-4351-0121-0

840:978-0-618-13384-0

543:Battle of Yanling

526:chariot from the

367:Crew and weaponry

288:mobile fortresses

249:of the character

165:

127:

126:

119:

118:

100:Standard Mandarin

61:

16:(Redirected from

1562:

1330:

1188:

1181:

1174:

1165:

1159:

1138:

1106:

1105:

1103:

1101:

1086:

1080:

1074:

1068:

1067:

1065:

1063:

1044:

1027:

1021:

1015:

1014:

1012:

1010:

1001:. Archived from

985:(257): 824–838.

970:

961:

960:

942:

933:

932:

930:

928:

913:

907:

906:

878:

872:

871:

851:

845:

844:

820:

814:

808:

802:

784:

778:

777:

761:

755:

754:

752:車:輿輪之緫名。夏后時奚仲所造。

734:

728:

727:

717:

708:

699:

698:

654:

645:

644:

622:

598:

254:

253:

203:War chariots at

166:

163:

159:

150:

142:

115:

114:

91:

77:

76:

62:

59:

52:

36:

21:

1570:

1569:

1565:

1564:

1563:

1561:

1560:

1559:

1520:

1519:

1518:

1509:

1389:

1375:Siege equipment

1321:

1291:

1198:

1192:

1162:

1156:

1141:

1135:

1119:

1115:

1110:

1109:

1099:

1097:

1088:

1087:

1083:

1075:

1071:

1061:

1059:

1058:on 17 July 2011

1046:

1045:

1030:

1022:

1018:

1008:

1006:

972:

971:

964:

957:

944:

943:

936:

926:

924:

915:

914:

910:

895:10.2307/2719276

880:

879:

875:

868:

853:

852:

848:

841:

822:

821:

817:

809:

805:

785:

781:

763:

762:

758:

736:

735:

731:

715:

710:

709:

702:

675:10.2307/2719276

656:

655:

648:

600:

599:

592:

587:

582:

560:

528:Terracotta Army

510:pincer movement

492:Chariot parts,

467:

435:

369:

317:

276:Battle of Mobei

272:Han–Xiongnu War

245:. Contemporary

197:

82:Literal meaning

63:

58:

34:

23:

22:

18:Chinese chariot

15:

12:

11:

5:

1568:

1566:

1558:

1557:

1552:

1547:

1542:

1537:

1532:

1522:

1521:

1515:

1514:

1511:

1510:

1508:

1507:

1502:

1501:

1500:

1493:

1486:

1481:

1474:

1462:

1459:Huolongchushui

1455:

1448:

1447:

1446:

1434:

1433:

1432:

1427:

1417:

1416:

1415:

1405:

1399:

1397:

1391:

1390:

1388:

1387:

1382:

1377:

1372:

1367:

1362:

1357:

1352:

1347:

1342:

1336:

1334:

1327:

1323:

1322:

1320:

1319:

1317:Late Qing Navy

1314:

1313:

1312:

1310:treasure ships

1301:

1299:

1293:

1292:

1290:

1289:

1284:

1279:

1274:

1269:

1264:

1259:

1254:

1249:

1244:

1239:

1234:

1232:Three Kingdoms

1229:

1224:

1221:Warring States

1214:

1208:

1206:

1200:

1199:

1193:

1191:

1190:

1183:

1176:

1168:

1161:

1160:

1154:

1139:

1133:

1116:

1114:

1111:

1108:

1107:

1096:on 7 July 2011

1081:

1069:

1028:

1016:

962:

955:

934:

921:People's Daily

908:

889:(1): 189–237.

873:

866:

846:

839:

815:

803:

779:

756:

729:

700:

669:(1): 189–237.

646:

613:(2): 135–168.

589:

588:

586:

583:

581:

578:

577:

576:

571:

566:

559:

556:

535:Battle of Muye

466:

463:

434:

431:

368:

365:

316:

313:

308:Three Kingdoms

223:Warring States

196:

193:

125:

124:

121:

120:

117:

116:

109:

103:

102:

96:

95:

94:Transcriptions

87:

86:

83:

79:

78:

71:

65:

64:

53:

45:

44:

41:

40:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1567:

1556:

1553:

1551:

1548:

1546:

1543:

1541:

1538:

1536:

1533:

1531:

1528:

1527:

1525:

1506:

1503:

1499:

1498:

1494:

1492:

1491:

1490:Xun Lei Chong

1487:

1485:

1482:

1480:

1479:

1478:San yan chong

1475:

1473:

1472:

1468:

1467:

1466:

1463:

1461:

1460:

1456:

1454:

1453:

1449:

1445:

1444:

1440:

1439:

1438:

1435:

1431:

1428:

1426:

1423:

1422:

1421:

1418:

1414:

1411:

1410:

1409:

1406:

1404:

1401:

1400:

1398:

1396:

1392:

1386:

1383:

1381:

1378:

1376:

1373:

1371:

1368:

1366:

1363:

1361:

1358:

1356:

1353:

1351:

1348:

1346:

1343:

1341:

1338:

1337:

1335:

1331:

1328:

1324:

1318:

1315:

1311:

1308:

1307:

1306:

1303:

1302:

1300:

1298:

1294:

1288:

1285:

1283:

1280:

1278:

1275:

1273:

1270:

1268:

1265:

1263:

1260:

1258:

1255:

1253:

1250:

1248:

1245:

1243:

1240:

1238:

1235:

1233:

1230:

1228:

1225:

1222:

1218:

1215:

1213:

1210:

1209:

1207:

1205:

1201:

1197:

1189:

1184:

1182:

1177:

1175:

1170:

1169:

1166:

1157:

1155:0-521-49781-7

1151:

1147:

1146:

1140:

1136:

1130:

1126:

1122:

1118:

1117:

1112:

1095:

1091:

1085:

1082:

1078:

1077:Beckwith 2009

1073:

1070:

1057:

1053:

1049:

1043:

1041:

1039:

1037:

1035:

1033:

1029:

1026:, p. 51.

1025:

1020:

1017:

1004:

1000:

996:

992:

988:

984:

980:

976:

969:

967:

963:

958:

952:

948:

941:

939:

935:

922:

918:

912:

909:

904:

900:

896:

892:

888:

884:

877:

874:

869:

863:

859:

858:

850:

847:

842:

836:

832:

828:

827:

819:

816:

813:, p. 43.

812:

811:Beckwith 2009

807:

804:

800:

799:p. 132 of 157

796:

795:

790:

789:

783:

780:

776:

772:

771:

766:

760:

757:

753:

749:

748:

747:Shuowen Jiezi

743:

739:

733:

730:

725:

721:

714:

707:

705:

701:

697:

692:

688:

684:

680:

676:

672:

668:

664:

660:

653:

651:

647:

643:

640:

636:

630:

626:

621:

616:

612:

608:

604:

597:

595:

591:

584:

579:

575:

572:

570:

567:

565:

562:

561:

557:

555:

552:

548:

544:

539:

536:

529:

525:

521:

517:

513:

511:

505:

501:

495:

490:

482:

476:

471:

464:

462:

460:

456:

452:

448:

444:

440:

432:

430:

428:

424:

420:

416:

412:

406:

404:

403:

398:

394:

390:

385:

383:

373:

366:

364:

360:

358:

353:

346:

342:

337:

330:

326:

321:

314:

312:

309:

304:

300:

297:, during the

296:

291:

289:

285:

281:

277:

273:

269:

265:

261:

256:

248:

244:

240:

236:

232:

224:

220:

213:

209:

206:

205:Shang dynasty

201:

194:

192:

190:

186:

182:

178:

174:

170:

160:

154:

146:

138:

134:

129:

122:

110:

108:

104:

101:

97:

92:

88:

84:

80:

72:

70:

66:

57:

51:

46:

42:

37:

32:

27:

19:

1495:

1488:

1476:

1469:

1457:

1450:

1441:

1408:Flamethrower

1339:

1144:

1124:

1113:Bibliography

1098:. Retrieved

1094:the original

1084:

1072:

1060:. Retrieved

1056:the original

1051:

1019:

1007:. Retrieved

1003:the original

982:

978:

946:

925:. Retrieved

920:

911:

886:

882:

876:

856:

849:

825:

818:

806:

792:

788:Guyi congshu

786:

782:

774:

768:

759:

751:

745:

732:

723:

719:

694:

666:

662:

632:

610:

606:

540:

532:

514:

506:

502:

498:

494:Zhou dynasty

458:

454:

450:

446:

442:

438:

436:

426:

418:

410:

407:

401:

396:

392:

388:

386:

381:

378:

361:

354:

350:

315:Construction

292:

266:against the

257:

228:

156:

132:

130:

128:

107:Hanyu Pinyin

60:(c. 400 BCE)

26:

1437:Hand cannon

1333:Traditional

1272:Jurchen Jin

1024:Gernet 1996

742:"Radical 車"

639:deer stones

635:khirigsuurs

524:Qin dynasty

475:Han dynasty

449:(正偏), four

341:Han dynasty

327:25–220 CE.

325:Eastern Han

264:Han dynasty

231:Xia dynasty

189:Han dynasty

187:during the

177:dagger-axes

85:war vehicle

1524:Categories

1452:Hu dun pao

1430:Fire lance

1403:Fire arrow

1009:6 December

927:10 October

580:References

239:Late Shang

54:A Chinese

1555:Warhorses

1497:Hongyipao

1413:Petroleum

1395:Gunpowder

1326:Equipment

1100:8 October

1062:6 October

1052:China.com

999:160406060

979:Antiquity

683:0073-0548

629:254751158

585:Citations

451:zhèngpiān

447:zhèngpiān

345:Liu Sheng

233:minister

1535:Chariots

1443:Huochong

1385:War cart

1365:Crossbow

1360:Elephant

1355:Polearms

1123:(2009).

558:See also

423:crossbow

331:, Hebei.

280:Wei Qing

235:Xi Zhong

173:Chariots

1471:Huo Che

1380:Stirrup

1340:Chariot

903:2719276

738:Xu Shen

691:2719276

564:Chariot

508:with a

393:róngyòu

382:róngyòu

268:Xiongnu

195:History

185:cavalry

158:zhànchē

113:zhànchē

56:chariot

1350:Swords

1345:Armour

1204:Armies

1152:

1131:

997:

953:

901:

864:

837:

794:Yupian

770:Shiben

689:

681:

642:Anyang

627:

421:弓) or

329:Anping

295:horses

284:Chanyu

155::

153:pinyin

147::

139::

1212:Shang

995:S2CID

899:JSTOR

775:奚仲作車。

716:(PDF)

687:JSTOR

625:S2CID

439:tú zù

208:Yinxu

169:China

1297:Navy

1287:Qing

1282:Ming

1277:Yuan

1267:Song

1262:Liao

1252:Tang

1217:Zhou

1150:ISBN

1129:ISBN

1102:2010

1064:2010

1011:2022

951:ISBN

929:2010

862:ISBN

835:ISBN

791:11,

679:ISSN

637:and

549:and

427:nŭ 弩

419:gōng

301:and

164:lit.

131:The

1247:Sui

1227:Han

987:doi

891:doi

671:doi

615:doi

551:Jin

547:Chu

459:jūn

455:shī

443:duì

415:bow

411:dùn

303:Han

299:Qin

1526::

1031:^

993:.

983:67

981:.

977:.

965:^

937:^

919:.

897:.

887:48

885:.

833:.

831:14

773:.

767:.

750:.

744:.

740:.

724:99

722:.

718:.

703:^

693:.

685:.

677:.

667:48

665:.

661:.

649:^

631:.

623:.

611:33

609:.

605:.

593:^

402:jĭ

397:gē

389:gē

290:.

191:.

161:;

151:;

149:战车

143:;

141:戰車

75:戰車

1223:)

1219:(

1187:e

1180:t

1173:v

1158:.

1137:.

1104:.

1066:.

989::

959:.

931:.

905:.

893::

870:.

843:.

726:.

673::

617::

425:(

417:(

347:.

252:車

214:.

135:(

33:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.