190:

82:

404:

788:, where millions of maps are generated every day with no direct input from a cartographer on label placement. Starting in the 1970s, the need for automation was recognized. Yoeli (1972) recognized that many of the placement guidelines espoused by Imhof (1962) and others had an algorithmic or mathematical character to them, which he attempted to specify in preparation for future placement algorithms.

31:

799:, and javascript mapping libraries. That said, because map labelling involves subjective judgments as well as rules or guidelines, most algorithms produce rules that are sub-optimal, especially in complex maps. When possible, cartographers generally use automated labels as a starting point, then refine them.

604:

The suggestions or 'rules' that follow are intended as guidelines to the intelligent positioning of type, not as inviolate laws to be followed blindly. In the practical application of these principles, it will seldom be possible to satisfy all the rules applying to a given situation. The cartographer

201:, most of the text identifies features, but there is also text that proscribes ("No Trailers"), describes ("private property"), categorizes ("... Canyon"), and locates ("Paunsaugunt Plateau"). The typeface subtly characterizes the map, being consistently used on all maps and publications of the U.S.

683:

When the point symbol is next to a line or area, especially one with a visually strong symbol (such as a city along a river or the sea), association is strengthened by placing the label on the same side as the point. This is frequently violated along shorelines because the water side generally has

209:

Text simultaneously serves several purposes on maps. In 1993, D. J. Fairbairn introduced a taxonomy of the purposes of text on maps, identifying fourteen types of text role. Since then, others, such as cartography textbooks, have described the variety of roles of text, with the following generally

666:

themselves (usually avoided by making the mask the background color rather than white). Moving the label with an attached leader line can also mitigate conflicts, although it reduces association slightly. Map symbols that are low in the visual hierarchy can often be overprinted without difficulty.

596:

examining many other parts of the map. Even Wood's 2000 update of Imhof, which adds many more guidelines, seems to still be based largely on best practices rather than science. That said, the durability of many of them, in the face of sweeping changes in technology and the capabilities of textual

587:

Determining the ideal location for each label that needs to be on the map is a complex process, with hundreds or thousands of labels competing for space, in addition to the map symbols which are usually more important. It is not a purely subjective decision process; for each label, some locations

591:

Early textbooks provided some general advice, but the primary contribution of Imhof's 1962 (English 1975) paper was to analyze the best practices of cartographers, and set forth a clear set of rules for label placement. Since then, there has been surprisingly little research into the validity of

149:

topographic maps, deriving a set of general principles and guidelines for type design and placement, which subsequent research has largely corroborated and further developed, and which forms the core canon on the topic found in modern cartography textbooks. In 1972, Pinhas Yoeli began to codify

679:

In terms of the directional relationship between the point and the label, some positions have better association and legibility than others. Most follow the preferences of Yoeli, who based it on Imhof. The label to the upper right of the point is generally accepted as preferred, with the other

665:

of the underlying feature. Usually, careful positioning of labels into empty space can avoid these conflicts, but when they cannot, masking or halos can be used to hide the underlying feature, as long as they do not obstruct so much of it as to make it unrecognizable or attract attention to

550:, also one the core visual variables, is typically used to match the value of associated symbols, although often darker, because lighter text can be less legible and have reproducibility problems, especially when printed. It is also commonly used for emphasis in the visual hierarchy.

475:

to indicate larger features or special types such as national capitals. Its role in visual hierarchy is debatable: at times, upper case seems to stand out because the characters are larger, but at other times it seems to recede because the characters are less interesting than Title

680:

corners acceptable. Directly to the left or to the right is problematic because the point and the label can run together, and centering the label above or below the point, which was acceptable to Imhof, is now generally discouraged because it can lead to association issues.

648:

so that "horizontal"=East-West helps to strengthen the understanding of direction and appears better aligned. Angled text appears more graceful and professional when placed along a slight circular arc rather than straight (unless it is following an angled straight linear

423:

extended his own visual variable system to including type styling in 1980 (in French). This work has largely been ignored in

English-speaking countries, although similar ideas have been developed by others. The most commonly cited and used typographic variables include:

609:

The "sense of the guidelines" Wood mentions are the aims of legibility, feature association, and a harmonious aesthetic of the map as ordered, professional, and clear. Almost all suggested guidelines can be deduced by evaluating possible labels according to those aims.

109:

or "copperplate" process. It was typical for the cartographer to not label the map himself, but to leave it to the master engraver. Text styles frequently changed with the tastes of the time, but were often very ornate, especially in non-map elements such as the title.

700:

Labels should generally follow the direction and curvature of the line feature. Text is legible on very simple, smooth curves, but is greatly reduced when text bends around sharp corners, so it is best placed in a relatively straight segment of the line, or along a

1336:

125:

in the mid-19th

Century significantly changed the production of maps and their labels, enabling the addition of printed type to maps using stamps, but map lettering still required a great deal of skill; this remained the state of the art until the development of

484:, the direction the characters are aligned, is used much more commonly with type than with map symbols. The most common reason to have text not be horizontal is to follow linear features, and sometimes elongated area features (which Imhof calls "ribbon-like").

655:(character, word, or line) can aid the association of the label with long or large features, such as spreading a label to fill a country, but this comes at the expense of legibility. Most sources suggest that spacing be used sparingly, carefully, and evenly.

435:, and serves much the same purpose, to differentiate nominal variables, most often to distinguish different classes of features (city vs. river vs. mountain vs. country). In addition to the following, Bertin also includes other shape variations, such as

708:

It is slightly preferable to place the label above the line rather than below. The most commonly stated reason is that most western languages have more ascenders than descenders, so the baseline is more of a straight line to follow the shape of the

335:

In his 1962 paper, Imhof reiterated the primary importance of legibility, and added the following requirements (listed here with modern terminology); he then showed how most specific guidelines and practices are derived from these principles:

748:

and its feature association, although if absolutely necessary, aligning the label so that it starts inside and crosses the boundary once to the outside is preferable to a centered label that crosses the boundary on both

307:: this may not be as problematic as in 1929, but even modern technologies (especially computer screens) can have difficulty with the relatively small sizes of map labels, especially in colors other than solid black.

644:, horizontal text is easiest to read, and upside-down text is most difficult. When north varies from the vertical direction (such as a tilted map orientation or a projection that distorts direction), following the

524:) is often varied on maps for a variety of purposes. For example, Imhof suggests using character spacing to spread an area label over the entire area feature, but counsels against doing the same for line labels.

100:

was an essential part of the skill set of the cartographer. This did not change with the advent of printing in the 15th

Century, because the dispersed placement of the text did not lend itself to the use of

588:

meet the aims above (especially legibility and association) better than others. An understanding of what makes some placement better than others thus streamlines the process of creating an effective map.

752:

For areas with an extended shape (which Imhof calls "ribbon-like"), such as reservoirs, their labels will have stronger association if they are oriented (with a slight curve) along the main axis of the

130:

in the 1950s. The photographic platemaking process meant that type could be produced on paper in a variety of ways, producing map labels of the same quality as book text. That said, as late as 1960,

770:

programs, provide a number of options for creating, editing, and storing the hundreds or even thousands of labels in a map. Each of these has advantages and disadvantages for particular situations.

530:, whether bold, black, light, or something in between, was considered by Bertin as a value-like variable, suggesting that it has an ordinal representation and a strong influence on visual hierarchy.

600:

Between Imhof, Wood, and other sources (especially textbooks), it is possible to list dozens of label placement rules. However, dutiful reliance on such lists can be misleading. According to Wood,

912:

Imhof, Eduard, “Die

Anordnung der Namen in der Karte,” Annuaire International de Cartographie II, Orell-Füssli Verlag, Zürich, 93-129, 1962. English Translation: "Positioning Names on Maps,"

718:

For a long line, especially in a dense network (such as rivers and roads), labels can be repeated occasionally to avoid confusion and aid association. Too much repetition can be overwhelming.

459:(which Bertin likens to orientation), whether roman, italic, or oblique, is typically used like typeface to differentiate feature types. Wood mentions the common use of italics for labeling

411:

Many of the aspects of type styling can be chosen and controlled by the cartographer when designing a particular label to serve the above purposes. In this sense, they are akin to the

744:

Placing the label completely inside the area is preferable, although it can be placed completely outside if the area is very small. Having a label cross the area boundary reduced its

637:

To aid association, labels should be placed as close to the associated map symbol as possible, without touching it (which would reduce legibility and recognition of the symbol).

795:) have been adapted to the labeling problem. Today, automated label placement tools are widespread, and is found in software as varied as GI, batch map renderers such as

734:

Many, but not all, sources suggest using letter and line spacing (within reason to not damage legibility) to fill more (but not all) of the area will aid association.

556:, additional symbols attached to the text, is used differently on maps than in block text. Common decorations such as underline and strikeout are rarely used, but a

715:

Character spacing is almost universally discouraged, but some cartographers find word spacing acceptable as long as the words can be easily connected by the reader.

632:, generally following standard guidelines for point, line, and area labels. Several exceptions were made to those guidelines when the situation necessitated such.

597:

design, and their continued use in professional practice, points to their strength. After decades, only a few of Imhof's original rules have fallen out of favor.

538:, one of Bertin's original visual variables, is rarely used in type to carry information on its own, although there are exceptions, such as using red (with its

823:

platforms also have this option, but some have the additional option of storing text as a dataset, enabling the same annotation to be reused in multiple maps.

712:

Association will be strongest if the label is placed near the midpoint of the line (or evenly spaced along the line if there are multiple copies of the label).

496:) is usually used for a piece of text in a similar fashion as the map symbol it is labeling: to indicate the geographic extent of the feature, to fit into the

385:, legibility, association, and hierarchy are typically listed as the most crucial of these aims, while conflict avoidance is one of the core foundations of

451:("type shape variation" in Bertin 1980), in addition to its common use to differentiate feature type, has a major influence on the aesthetics of the map.

181:

became available, and it became easy to place text anywhere on the map. This completed the shift of skill in map typography from construction to design.

1183:. The Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge (3rd Quarter 2017 Edition), John P. Wilson (ed.). DOI: 10.22224/gistbok/2017.3.2

572:

are forms of decoration that are added to aid feature association when a label cannot be placed adjacent to the feature. Another form of decoration are

687:

Spacing is generally discouraged, especially on point labels broken into multiple lines. Being "set tight" helps the label look like a single object.

661:: when labels cross map symbols (especially those that are of high visual weight), they will be less legible, and obscure the shape and reduce the

675:

This also includes area features that are too small to label inside, in which case an exterior label treats the area symbol as a point symbol.

542:

of danger) for warnings. Instead, hue is usually used to match the text to the hue of the symbol it is labeling, strengthening its association.

564:, hiding the underlying features around a label, is often used to increase legibility where there are many features that cannot be avoided. A

1124:

1074:

292:

cartographer

Captain John G. Withycombe, in a critique of the state of map lettering, listed five essential aims of cartographic typography.

141:

A significant turning point was "Die

Anordnung der Namen in der Karte", a 1962 essay (re-published in English in 1975) by Swiss cartographer

331:: the various typefaces and styles used should work and look good together, and should produce an overall look of order and professionalism.

807:

The other option is to store the location and style of each label in the map data, just like the rest of the map; this is typically called

343:: the reader must be able to clearly connect each label to the feature it is labeling. Withycombe's contrast is an important part of this.

819:, it is stored in the map document in the same way as other geometry, allowing for manual editing of content, position, and style. Many

784:

Manually placing a large number of labels is a very time-consuming process, even in modern software; this is especially problematic in

241:," a note on the history of a building, or varying the size of city labels according to population to the size of the city symbols.

355:: labels should help to indicate the spatial extent of the features they label, as well as their distinction from other features

237:

information that cannot be directly derived from the map symbols or corroborating the symbolized information, such as "Box Lake

622:

349:: many of the above aims can be aided by placing labels so they do not overlap too many map features, especially other labels.

763:

727:

These guidelines also apply to clusters of points or small areas being labeled as a single feature, such as an island chain.

174:

138:

were still in common usage through the 1980s, encouraging a very simplistic functional style over any aesthetic character.

645:

301:: readers must be able to read the text, especially, as Withycombe states, "when superimposed upon the detail of a map."

745:

702:

662:

625:

471:("sign shape variation" in Bertin 1980) has a more ordinal sense than typeface or posture, and many cartographers use

1228:

145:, considered the greatest European cartographer of his day. Imhof analyzed the best maps he could find, such as the

194:

154:. In 2000, Clifford Wood extended Imhof's guidelines, based on the intervening 25 years of research and practice.

779:

386:

151:

791:

Since then, increasingly robust algorithms have been developed, and existing computational algorithms (such as

613:

From the various lists of placement guidelines, the following is a sample of those most commonly emphasized:

279:

the map with a particular aesthetic feel, such as using a typeface that looks playful, modern, or historical.

73:

to the present, their labeling has been dependent on the general techniques and technologies of typography.

1349:

Kakoulis, Konstantinos G., Ioannis G. Tollis (2013) "Labeling

Algorithms," Chapter 15 in R. Tamassia, ed.,

696:

Often, these guidelines are also followed for area features with a very linear shape, such as wide rivers.

106:

70:

1363:

1404:

1376:

975:

Wood, Clifford H. (2000). "A Descriptive and

Illustrated Guide for Type Placement on Small Scale Maps".

202:

189:

684:

far fewer features and labels to contend with, so placing labels in the "empty space" aids legibility.

34:

An example of a cartographic style guide for a particular institution, including typography standards.

1399:

578:, symbols attached to route numbers, usually to make them look like the signs seen along the highway.

177:, greatly increased and facilitated the more thoughtful design and use of type on maps. A wealth of

842:

812:

792:

539:

135:

42:

81:

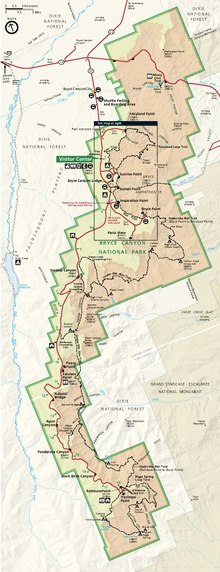

1251:

1157:

992:

493:

158:

131:

731:

All else being equal, a label location near the center of the feature will maximize association.

1197:

1120:

1070:

816:

403:

321:

162:

53:, together representing geographic features and their properties. It is also often called map

377:: "Names should not be evenly dispersed over the map, nor should names be densely clustered."

247:

features that are not shown by a distinct symbol, such as "Arabian Sea" or "Rocky

Mountains."

1279:

1243:

1209:

1149:

1044:

984:

940:

497:

368:

359:

264:

127:

85:

432:

412:

289:

170:

443:

or patterned fills, which are used less often in maps due to their effect on legibility.

767:

574:

510:

504:

420:

166:

114:

1393:

1255:

996:

593:

546:

105:. Instead, printed maps, including text, were drawn, engraved, and printed using the

17:

605:

must apply the total 'sense' of the guidelines, accepting some and rejecting others.

515:

367:

for each feature, Withycombe's contrast in lettering can be used to strengthen the

142:

102:

1247:

1180:

1115:

Slocum, Terry A.; McMaster, Robert B.; Kessler, Fritz C.; Howard, Hugh H. (2009).

785:

467:

460:

118:

97:

93:

1048:

30:

837:

416:

364:

297:

122:

66:

50:

1229:"Bertin's forgotten typographic variables and new typographic visualization"

1213:

988:

944:

146:

1283:

317:) contributes not only to aesthetic appeal, but also to the two aims above.

325:: labels for different kinds of features should themselves look different.

263:

the conceptual structure of the map as a whole, such as strengthening the

832:

738:

472:

447:

314:

178:

134:

still advised new cartographers to be skilled in freehand lettering, and

88:

map of Europe, about 1600, produced (including text) by copper engraving.

1270:

1161:

1035:

Fairbairn, D.J. (December 1993). "On the nature of cartographic text".

520:

455:

796:

1153:

1340:, IBM ILOG JViews Enterprise V8.7 Help. Accessed 18 September 2012

1198:"Classification typographique : Voulez-vous jouer avec mon A"

762:

The software that is commonly used to create maps, including both

621:

620:

402:

188:

80:

29:

1017:

Dent, Borden D.; Torguson, Jeffrey S.; Hodler, Thomas W. (2009).

741:

for area symbols, claiming that capital letters fill more space.

629:

488:

398:

198:

931:

Yoeli, Pinhas (1972). "The Logic of

Automated Map Lettering".

820:

534:

46:

463:

features, due to its curving form that suggests water flow.

313:: Withycombe points out that careful choice of "alphabet" (

1140:

Withycombe, John Gidley (May 1929). "Lettering on Maps".

150:

Imhof's guidelines mathematically, setting the stage for

1324:

IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics

1322:

Been, K., Daiches, E., Yap, C., Dynamic Map Labeling,

1272:

Assessing visual variables of cartographic text design

173:, combined with the improving design capabilities of

1300:(2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2015). 89-90.

45:, is the craft of designing and placing text on a

1069:(2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 105–108.

592:these rules, especially compared to the numerous

407:Typographic style variables commonly used in maps

1313:(2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2015). 91.

1311:GIS Cartography: A Guide to Effective Map Design

1298:GIS Cartography: A Guide to Effective Map Design

1060:

1058:

602:

1236:Cartography and Geographic Information Science

889:(2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 133–143.

862:

860:

858:

1191:

1189:

1110:

1108:

1106:

500:, or to represent some quantitative variable.

381:In subsequent literature, textbooks, and the

217:unique features, such as "The United Kingdom"

8:

1100:, 1st edition, The Guilford Press, pp.43-56.

439:(condensed, compressed, extended, etc.) and

1351:Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization

1092:

1090:

1088:

1086:

1065:Kraak, Menno-Jan; Ormeling, Ferjan (2003).

1030:

1028:

880:

878:

815:, like points, lines, and polygons, and in

1175:

1173:

1171:

1067:Cartography: Visualization of Spatial Data

1012:

1010:

1008:

1006:

970:

968:

966:

964:

962:

960:

958:

956:

954:

65:is more in line with the general usage of

1337:Introduction to automatic label placement

492:(usually measured by the block height in

284:Aims and goals of cartographic typography

871:(2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 243–263.

926:

924:

922:

908:

906:

904:

902:

900:

898:

896:

854:

96:, the text on maps was hand drawn, and

1227:Brath, Richard; Banissi, Ebad (2019).

1117:Thematic Cartography and Visualization

223:features into groups, such as "Smith

7:

1119:. Prentice Hall. pp. 202–210.

25:

431:is akin to shape in the original

1021:. McGraw-Hill. pp. 226–245.

1019:Cartography: Thematic Map Design

185:Purposes and goals of map labels

764:geographic information systems

175:Geographic information systems

1:

1248:10.1080/15230406.2018.1516572

257:action, such as "No Camping."

916:, V.2 #2 (1975), pp.128-144

811:. Text can be modeled as a

383:GIS&T Body of Knowledge

92:For most of the history of

1421:

1049:10.1179/000870493787860157

777:

737:Some cartographers prefer

396:

195:Bryce Canyon National Park

136:mechanical lettering tools

1383:, accessed 17 August 2020

1366:. Accessed 1 October 2016

1202:Communication et Langages

914:The American Cartographer

867:Robinson, Arthur (1960).

780:Automatic label placement

774:Automatic label placement

387:Automatic label placement

152:Automatic label placement

1381:ArcGIS Pro Documentation

1353:, CRC Press, pp.489-515.

1196:Bertin, Jacques (1980).

1142:The Geographical Journal

1098:Principles of Map Design

1037:The Cartographic Journal

977:The Cartographic Journal

1278:. University of Ghent.

1214:10.3406/colan.1980.1369

989:10.1179/caj.2000.37.1.5

945:10.1179/caj.1972.9.2.99

869:Elements of Cartography

758:Digital text management

723:Area (polygon) features

371:of features in the map.

210:being the most common:

161:around 1990, including

27:Text used to label maps

1309:Peterson, Gretchen N.

1296:Peterson, Gretchen N.

746:figure-ground contrast

663:figure-ground contrast

633:

607:

594:psychophysical studies

408:

206:

89:

35:

1326:, Vol. 12, No.5, 2006

885:Raisz, Erwin (1948).

624:

406:

203:National Park Service

192:

84:

33:

18:Labeling (map design)

1269:Deeb, Rasha (2015).

1179:Guidero, E. (2017).

1096:Tyner, J. A. (2010)

933:Cartographic Journal

705:version of the line.

508:between characters (

887:General Cartography

843:Cartographic design

813:Geometric primitive

793:Simulated annealing

273:the map as a whole.

113:The development of

43:cartographic design

634:

617:General guidelines

409:

347:Conflict avoidance

207:

159:Desktop publishing

132:Arthur H. Robinson

90:

49:in support of the

41:, as an aspect of

36:

1126:978-0-13-229834-6

1076:978-0-13-088890-7

817:graphics software

803:Stored annotation

163:graphics software

69:. Throughout the

16:(Redirected from

1412:

1384:

1373:

1367:

1362:GIS Dictionary,

1360:

1354:

1347:

1341:

1333:

1327:

1320:

1314:

1307:

1301:

1294:

1288:

1287:

1277:

1266:

1260:

1259:

1233:

1224:

1218:

1217:

1193:

1184:

1177:

1166:

1165:

1137:

1131:

1130:

1112:

1101:

1094:

1081:

1080:

1062:

1053:

1052:

1032:

1023:

1022:

1014:

1001:

1000:

972:

949:

948:

928:

917:

910:

891:

890:

882:

873:

872:

864:

498:visual hierarchy

433:visual variables

413:visual variables

369:Visual hierarchy

265:visual hierarchy

128:Photolithography

86:Abraham Ortelius

21:

1420:

1419:

1415:

1414:

1413:

1411:

1410:

1409:

1390:

1389:

1388:

1387:

1374:

1370:

1361:

1357:

1348:

1344:

1334:

1330:

1321:

1317:

1308:

1304:

1295:

1291:

1284:1854/LU-5938940

1275:

1268:

1267:

1263:

1231:

1226:

1225:

1221:

1195:

1194:

1187:

1178:

1169:

1154:10.2307/1784644

1139:

1138:

1134:

1127:

1114:

1113:

1104:

1095:

1084:

1077:

1064:

1063:

1056:

1034:

1033:

1026:

1016:

1015:

1004:

974:

973:

952:

930:

929:

920:

911:

894:

884:

883:

876:

866:

865:

856:

851:

829:

805:

782:

776:

760:

725:

694:

673:

619:

585:

575:highway shields

401:

395:

305:Reproducibility

290:Ordnance Survey

286:

193:In this map of

187:

171:inkjet printers

79:

71:history of maps

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

1418:

1416:

1408:

1407:

1402:

1392:

1391:

1386:

1385:

1368:

1355:

1342:

1328:

1315:

1302:

1289:

1276:(Dissertation)

1261:

1242:(2): 119–139.

1219:

1185:

1167:

1148:(5): 429–435.

1132:

1125:

1102:

1082:

1075:

1054:

1043:(2): 104–111.

1024:

1002:

950:

918:

892:

874:

853:

852:

850:

847:

846:

845:

840:

835:

828:

825:

804:

801:

778:Main article:

775:

772:

768:graphic design

759:

756:

755:

754:

750:

742:

735:

732:

724:

721:

720:

719:

716:

713:

710:

706:

693:

690:

689:

688:

685:

681:

672:

671:Point features

669:

668:

667:

656:

650:

638:

618:

615:

584:

581:

580:

579:

551:

543:

531:

525:

501:

485:

479:

478:

477:

464:

452:

421:Jacques Bertin

397:Main article:

394:

391:

379:

378:

372:

356:

350:

344:

333:

332:

326:

318:

308:

302:

285:

282:

281:

280:

277:Characterizing

274:

268:

258:

248:

242:

228:

218:

186:

183:

167:laser printers

115:Photoengraving

78:

75:

26:

24:

14:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1417:

1406:

1403:

1401:

1398:

1397:

1395:

1382:

1378:

1372:

1369:

1365:

1359:

1356:

1352:

1346:

1343:

1339:

1338:

1332:

1329:

1325:

1319:

1316:

1312:

1306:

1303:

1299:

1293:

1290:

1285:

1281:

1274:

1273:

1265:

1262:

1257:

1253:

1249:

1245:

1241:

1237:

1230:

1223:

1220:

1215:

1211:

1207:

1203:

1199:

1192:

1190:

1186:

1182:

1176:

1174:

1172:

1168:

1163:

1159:

1155:

1151:

1147:

1143:

1136:

1133:

1128:

1122:

1118:

1111:

1109:

1107:

1103:

1099:

1093:

1091:

1089:

1087:

1083:

1078:

1072:

1068:

1061:

1059:

1055:

1050:

1046:

1042:

1038:

1031:

1029:

1025:

1020:

1013:

1011:

1009:

1007:

1003:

998:

994:

990:

986:

982:

978:

971:

969:

967:

965:

963:

961:

959:

957:

955:

951:

946:

942:

939:(2): 99–108.

938:

934:

927:

925:

923:

919:

915:

909:

907:

905:

903:

901:

899:

897:

893:

888:

881:

879:

875:

870:

863:

861:

859:

855:

848:

844:

841:

839:

836:

834:

831:

830:

826:

824:

822:

818:

814:

810:

802:

800:

798:

794:

789:

787:

781:

773:

771:

769:

765:

757:

751:

747:

743:

740:

736:

733:

730:

729:

728:

722:

717:

714:

711:

707:

704:

699:

698:

697:

692:Line features

691:

686:

682:

678:

677:

676:

670:

664:

660:

657:

654:

651:

647:

643:

639:

636:

635:

631:

627:

623:

616:

614:

611:

606:

601:

598:

595:

589:

582:

577:

576:

571:

567:

563:

559:

555:

552:

549:

548:

544:

541:

537:

536:

532:

529:

526:

523:

522:

518:, and lines (

517:

513:

512:

507:

506:

502:

499:

495:

491:

490:

486:

483:

480:

474:

470:

469:

465:

462:

458:

457:

453:

450:

449:

445:

444:

442:

438:

434:

430:

427:

426:

425:

422:

418:

417:map symbology

414:

405:

400:

392:

390:

388:

384:

376:

373:

370:

366:

362:

361:

357:

354:

351:

348:

345:

342:

339:

338:

337:

330:

327:

324:

323:

319:

316:

312:

309:

306:

303:

300:

299:

295:

294:

293:

291:

283:

278:

275:

272:

269:

266:

262:

259:

256:

252:

249:

246:

243:

240:

236:

232:

229:

226:

222:

219:

216:

213:

212:

211:

204:

200:

196:

191:

184:

182:

180:

176:

172:

168:

164:

160:

155:

153:

148:

144:

139:

137:

133:

129:

124:

123:wax engraving

120:

116:

111:

108:

104:

99:

95:

87:

83:

76:

74:

72:

68:

64:

60:

56:

52:

48:

44:

40:

32:

19:

1405:Infographics

1380:

1371:

1364:'Annotation'

1358:

1350:

1345:

1335:

1331:

1323:

1318:

1310:

1305:

1297:

1292:

1271:

1264:

1239:

1235:

1222:

1208:(1): 70–75.

1205:

1201:

1145:

1141:

1135:

1116:

1097:

1066:

1040:

1036:

1018:

980:

976:

936:

932:

913:

886:

868:

808:

806:

790:

783:

761:

726:

695:

674:

659:Overprinting

658:

652:

641:

640:In terms of

612:

608:

603:

599:

590:

586:

573:

569:

565:

561:

557:

553:

545:

533:

527:

519:

509:

503:

487:

481:

466:

461:hydrographic

454:

446:

440:

436:

428:

410:

393:Type styling

382:

380:

375:Distribution

374:

358:

352:

346:

340:

334:

328:

320:

310:

304:

296:

287:

276:

270:

260:

254:

250:

244:

238:

234:

230:

224:

221:Categorizing

220:

214:

208:

157:The rise of

156:

143:Eduard Imhof

140:

112:

103:Movable type

91:

62:

58:

54:

38:

37:

1400:Cartography

983:(1): 5–18.

786:Web mapping

642:orientation

570:leader line

540:connotation

482:Orientation

419:; in fact,

363:: like the

341:Association

271:Beautifying

255:Proscribing

251:Prescribing

215:Identifying

119:Zincography

98:Calligraphy

94:Cartography

51:map symbols

1394:Categories

1377:Annotation

1181:Typography

849:References

838:Typography

809:annotation

554:Decoration

298:Legibility

261:Organizing

235:explaining

231:Describing

67:typography

63:typography

39:Typography

1256:134450553

997:129481053

649:feature).

646:graticule

583:Placement

360:Hierarchy

288:In 1929,

179:typefaces

147:Swisstopo

59:lettering

833:Toponymy

827:See also

739:All caps

709:feature.

703:smoothed

511:tracking

473:ALL CAPS

448:Typeface

322:Contrast

315:typeface

245:Locating

107:Intaglio

55:labeling

1162:1784644

653:Spacing

628:Map of

568:box or

566:callout

521:leading

505:Spacing

456:Posture

441:texture

365:symbols

329:Harmony

77:History

1375:esri,

1254:

1160:

1123:

1073:

995:

797:Mapnik

753:shape.

749:sides.

528:Weight

494:points

353:Extent

169:, and

121:, and

61:, but

1252:S2CID

1232:(PDF)

1158:JSTOR

993:S2CID

547:Value

516:words

476:Case.

437:width

311:Style

239:(dry)

1121:ISBN

1071:ISBN

766:and

630:Peru

562:mask

558:halo

489:Size

468:Case

429:Form

399:Font

225:Park

199:Utah

1280:hdl

1244:doi

1210:doi

1150:doi

1045:doi

985:doi

941:doi

821:GIS

626:CIA

560:or

535:Hue

514:),

415:of

253:or

233:or

57:or

47:map

1396::

1379:,

1250:.

1240:46

1238:.

1234:.

1206:45

1204:.

1200:.

1188:^

1170:^

1156:.

1146:73

1144:.

1105:^

1085:^

1057:^

1041:30

1039:.

1027:^

1005:^

991:.

981:37

979:.

953:^

935:.

921:^

895:^

877:^

857:^

389:.

197:,

165:,

117:,

1286:.

1282::

1258:.

1246::

1216:.

1212::

1164:.

1152::

1129:.

1079:.

1051:.

1047::

999:.

987::

947:.

943::

937:9

267:.

227:"

205:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.