208:

pipelines that exist in most modern oil fields. Aircraft pilots reported that hundreds of square miles of west Texas were lit at night from the fires of thousands of gas flares, and the people in

Midland reported seeing what appeared to be a false sunrise in the east shortly after each sunset. In 1953 the Railroad Commission prohibited the wasteful practice, shutting down all wells in the field until a recovery system could be built. After a series of lawsuits and court battles, the Railroad Commission backed down, compromising with the operators by allowing them a set number of days per month during which they could pump oil and flare gas. The overall gas reserves of the field were estimated to be over two trillion cubic feet; during the peak of the early 1950s gas-flaring, over 220 million cubic feet (6,200,000 m) per day were burned.

188:

to profit in the huge oil play. Even the professional geologists could not agree on what was wrong: in

October, 1951, a convention in Midland of hundreds of engineers and petroleum geologists reached no consensus on the issues with the field, although the peculiar and irregularly fractured nature of the oil-bearing rocks seemed to be a large part of the problem. In May 1952, there were more than 1,630 Spraberry wells in the Midland basin, most recently drilled, but local enthusiasm had ended. In the following years, each operator developed its own methods of dealing with the unusual reservoir, and began to employ a technique known as "

179:

1949, when the same company drilled well Lee 2-D, which produced 319 barrels per day (50.7 m/d) – hardly a spectacular discovery, but enough to pique the interest of numerous independent operators looking for opportunity around

Midland. In 1950 and 1951, several other independent oil companies drilled productive wells separated by great distances, establishing that the formation was at least 150 miles (240 km) long, and beginning a frenzy of drilling in the region surrounding Midland.

192:" – forcing water down wells at extreme pressure, causing the rocks to fracture further, resulting in increased oil flow. This was moderately successful, and development of the Spraberry continued, albeit with greatly diminished expectations for massive output. Yet another method of fracturing the rocks to increase production was to pump a mixture of soap and kerosene, followed by a coarse-grained sand, also under intense pressure.

204:, the regulatory body which decided on well spacing and production quota, to require 80-acre (320,000 m), and then even 160-acre (0.65 km) spacing to allow each drilling site to be profitable. Many of the initial wells were abandoned in the next few years as they ran out of oil; modern enhanced recovery techniques, such as carbon dioxide injection, were not yet available.

20:

216:

period. In the 21st century, newer technologies such as carbon dioxide flooding have been used to increase production. Even with these advances, the

Spraberry retains about 90% of its original calculated reserves, largely due to the difficulty of recovery. As of 2009, there were approximately 9,000 active wells in the Spraberry Trend.

178:

The first well drilled into the formation was by

Seaboard Oil Company in 1943, on land owned by farmer Abner Spraberry in Dawson County. While the well bore showed an oil-bearing unit had been found, and hence received Spraberry's name, it did not produce commercial quantities of oil. That changed in

187:

required a well to produce 50,000 barrels (7,900 m) just to break even in the face of the low federally mandated price of $ 2.58/barrel. Local companies that had been skeptical of the

Spraberry since the beginning of the boom did not suffer the losses of the outsiders who had come in expecting

215:

technologies, such as waterflooding. In the 1970s, as the price of oil went up, drilling and production proceeded; while

Spraberry wells were never abundant producers, during periods of high prices they could provide dependable profits for oil companies, and the local economy entered its strongest

48:

in the early 1950s. The oil in the

Spraberry, however, proved difficult to recover. After about three years of enthusiastic drilling, during which most of the initially promising wells showed precipitous and mysterious production declines, the area was dubbed "the world's largest unrecoverable oil

195:

During the initial boom period the

Spraberry promoters carried out an aggressive campaign to bring in outside investment, making exorbitant claims of the potential easy profit with the vast reserves of oil. As every well drilled into the Spraberry Sands anywhere in the Midland Basin found oil, at

207:

For a period in the 1950s the abundant natural gas in the reservoir was simply flared off – burned above the wellhead – since no recovery infrastructure existed. Steel was expensive, transport costs high, and profit margins from the field were too low to allow the development of the sort of gas

199:

Using the normal 40-acre (160,000 m) spacing employed elsewhere in West Texas proved impossible on the

Spraberry; wells that close competed against each other, as yields per-acre from the difficult reservoir were dropping into the hundreds of barrels rather than the expected thousands. Oil

182:

Unfortunately for most of the speculators, investors, and outside independent oil companies, most of the newly drilled wells behaved badly; they produced oil nicely for a short time, and then production fell off sharply, with wells often failing to break even. In 1950, the cost of drilling and

196:

least initially, it seemed at first that their claims were not completely without merit. Yet their tactics were not subtle: one group of promoters from Los Angeles brought in a group of Hollywood models, and had these women photographed on the drilling rigs, working the equipment in the nude.

169:

Shaly rocks make up 87% of the Spraberry, with the oil-bearing sands and siltstones present sometimes in thin layers between them. The best-producing zone is at an average depth of 6,800 feet (2,100 m) across the entire region, which is about 150 miles (240 km) long by 70 wide.

43:

farmer who owned the land containing the 1943 discovery well. The Spraberry Trend is itself part of a larger oil-producing region known as the Spraberry-Dean Play, within the Midland Basin. Discovery and development of the field began the postwar economic boom in the nearby city of

109:

Counties. Elevations are generally between 2,500 and 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level, and the terrain varies from flat to rolling, with occasional canyons, known locally as "draws", cutting through the plateau. Drainage is to the east, via the

52:

In 2007, the U.S. Department of Energy ranked The Spraberry Trend third in the United States by total proved reserves, and seventh in total production. Estimated reserves for the entire Spraberry-Dean unit exceeded 10 billion barrels

157:

as it migrated upward from source rocks until encountering impermeable barriers, either in the internal shaly members or the overlying impermeable formation. Unlike many of the oil-bearing rocks of West Texas, however, the very low

256:

294:

Scott L. Montgomery, David S. Schechter, and John Lorenz. "Advanced Reservoir Characterization to Evaluate Carbon Dioxide Flooding, Spraberry Trend, Midland Basin, Texas." AAPG Bulletin

618:

554:

613:

31:(also known as the Spraberry Field, Spraberry Oil Field, and Spraberry Formation; sometimes erroneously written as Sprayberry) is a large oil field in the

133:

All of the Spraberry Trend oil fields produce from a single enormous sedimentary unit known as the Spraberry Sand, which consists of complexly mixed fine

39:, covering large parts of six counties, and having a total area of approximately 2,500 square miles (6,500 km). It is named for Abner Spraberry, the

623:

598:

253:

608:

603:

65:

The Spraberry Trend covers a large area – around 2,500 square miles (6,500 km) – and includes portions of two Texas geographical regions, the

125:

Aside from activities associated with oil production, transport, and storage, predominant land use in the area includes ranching and farming.

433:

413:

232:

211:

The field grew in the 1960s with the annexation of several adjacent oil pools, and overall production increased with the implementation of

543:

524:

346:

324:

528:

57:

10 m), and by the end of 1994, the field had reported a total production of 924 million barrels (146,900,000 m).

163:

32:

593:

201:

350:

145:, deposited in a deep water environment distinguished by channel systems and their associated submarine fans, all of

327:

546:

23:

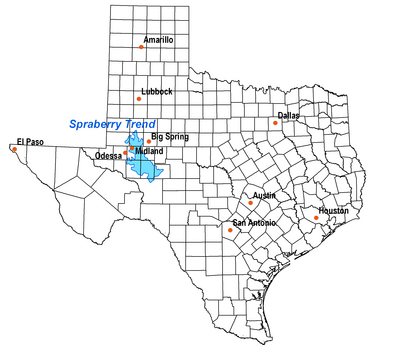

Location of the Spraberry Trend in Texas, showing major and nearby cities. Black lines are county boundaries.

86:

122:. Native vegetation includes scrub and grasslands, with trees such as cottonwoods along the watercourses.

492:

Page on the Spraberry Trend, at Harold Vance Department of Petroleum Engineering, Texas A&M University

115:

102:

212:

166:

hamper economic oil recovery. The rocks are naturally fractured, further complicating hydrocarbon flow.

106:

90:

293:

189:

98:

94:

78:

40:

360:

82:

74:

304:

154:

539:

520:

342:

320:

184:

517:

Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling, and Production, 2nd edition.

491:

260:

70:

480:

393:

271:

66:

45:

587:

111:

282:

36:

569:

556:

142:

134:

119:

159:

138:

146:

19:

150:

18:

97:

Counties, although the underlying geologic unit also touches

73:. As most often defined, the Spraberry includes portions of

272:

Spraberry-Dean Sandstone Fields: Handbook of Texas Online

481:

Spraberry-Dean Sandstone Fields: Handbook of Texas Online

394:

Spraberry-Dean Sandstone Fields: Handbook of Texas Online

200:

companies resorted to the unusual step of asking the

319:

p. 85. Multi-Science Publishing Company, Ltd. 2004.

153:, and typically pinch-out updip. Oil accumulated in

317:

Economics of Petroleum Production: Value and Worth.

16:Large oil field in the Permian Basin of West Texas

183:putting down 8,000 feet (2,400 m) of steel

339:Fundamentals of numerical reservoir simulation.

8:

538:. 2007. Texas A&M University Press .

434:1951 Time Magazine article on the Spraberry

414:1951 Time Magazine article on the Spraberry

235:1951 Time Magazine article on the Spraberry

225:

536:Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

534:Roger M. Olien, Diana Davids Hinton:

7:

619:Geography of Glasscock County, Texas

149:age. The sands are interbedded with

614:Geography of Midland County, Texas

365:. United States Geological Survey.

14:

624:Geography of Martin County, Texas

599:Geography of Reagan County, Texas

609:Geography of Upton County, Texas

604:Geography of Irion County, Texas

1:

202:Railroad Commission of Texas

502:Montgomery/Schechter/Lorenz

137:and calcareous or silicate

640:

315:Ian Lerche, Sheila North.

254:Top 100 Oil and Gas Fields

404:Olien/Hinton, pp. 100-101

444:Olien/Hinton, p. 103-104

384:Olien/Hinton, pp. 99-100

375:Olien/Hinton, pp. 99-101

283:Texas Ecological Regions

519:PennWell Books, 2001.

453:Olien/Hinton, p. 105-7

363:Permian Basin Province

24:

22:

570:31.7416°N 101.8744°W

471:Olien/Hinton, p. 106

424:Olien/Hinton, p. 101

244:Olien/Hinton, p. 103

594:Oil fields in Texas

566: /

155:stratigraphic traps

575:31.7416; -101.8744

259:2009-05-15 at the

25:

547:Google Books link

529:Google Books link

515:Hyne, Norman J.

341:Elsevier, 1977.

337:Donald Peaceman.

213:enhanced recovery

118:. The climate is

631:

581:

580:

578:

577:

576:

571:

567:

564:

563:

562:

559:

503:

500:

494:

489:

483:

478:

472:

469:

463:

460:

454:

451:

445:

442:

436:

431:

425:

422:

416:

411:

405:

402:

396:

391:

385:

382:

376:

373:

367:

361:Mahlon M. Ball,

358:

352:

335:

329:

313:

307:

305:Final Report ...

302:

296:

291:

285:

280:

274:

269:

263:

251:

245:

242:

236:

230:

56:

639:

638:

634:

633:

632:

630:

629:

628:

584:

583:

574:

572:

568:

565:

560:

557:

555:

553:

552:

512:

507:

506:

501:

497:

490:

486:

479:

475:

470:

466:

461:

457:

452:

448:

443:

439:

432:

428:

423:

419:

412:

408:

403:

399:

392:

388:

383:

379:

374:

370:

359:

355:

336:

332:

314:

310:

303:

299:

292:

288:

281:

277:

270:

266:

261:Wayback Machine

252:

248:

243:

239:

233:Time (magazine)

231:

227:

222:

190:hydrofracturing

176:

131:

71:Edwards Plateau

63:

54:

29:Spraberry Trend

17:

12:

11:

5:

637:

635:

627:

626:

621:

616:

611:

606:

601:

596:

586:

585:

550:

549:

532:

511:

508:

505:

504:

495:

484:

473:

464:

455:

446:

437:

426:

417:

406:

397:

386:

377:

368:

353:

330:

308:

297:

286:

275:

264:

246:

237:

224:

223:

221:

218:

175:

172:

130:

127:

116:Colorado River

67:Llano Estacado

62:

59:

15:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

636:

625:

622:

620:

617:

615:

612:

610:

607:

605:

602:

600:

597:

595:

592:

591:

589:

582:

579:

548:

545:

544:1-58544-606-8

541:

537:

533:

530:

526:

525:0-87814-823-X

522:

518:

514:

513:

509:

499:

496:

493:

488:

485:

482:

477:

474:

468:

465:

459:

456:

450:

447:

441:

438:

435:

430:

427:

421:

418:

415:

410:

407:

401:

398:

395:

390:

387:

381:

378:

372:

369:

366:

364:

357:

354:

351:

348:

347:0-444-41625-0

344:

340:

334:

331:

328:

326:

325:0-906522-24-2

322:

318:

312:

309:

306:

301:

298:

295:

290:

287:

284:

279:

276:

273:

268:

265:

262:

258:

255:

250:

247:

241:

238:

234:

229:

226:

219:

217:

214:

209:

205:

203:

197:

193:

191:

186:

180:

173:

171:

167:

165:

161:

156:

152:

148:

144:

140:

136:

128:

126:

123:

121:

117:

113:

108:

104:

100:

96:

92:

88:

84:

80:

76:

72:

68:

60:

58:

50:

47:

42:

41:Dawson County

38:

34:

33:Permian Basin

30:

21:

551:

535:

516:

498:

487:

476:

467:

458:

449:

440:

429:

420:

409:

400:

389:

380:

371:

362:

356:

349:. p. 131.

338:

333:

316:

311:

300:

289:

278:

267:

249:

240:

228:

210:

206:

198:

194:

181:

177:

168:

164:permeability

132:

124:

112:Concho River

64:

51:

28:

26:

573: /

561:101°52′28″W

462:USGS, p. 14

588:Categories

558:31°44′30″N

510:References

49:reserve."

37:West Texas

143:siltstone

135:sandstone

120:semi-arid

87:Glasscock

257:Archived

160:porosity

139:mudstone

103:Crockett

69:and the

174:History

147:Permian

129:Geology

114:to the

107:Andrews

91:Midland

61:Setting

46:Midland

542:

523:

345:

323:

185:casing

151:shales

105:, and

99:Dawson

95:Martin

93:, and

79:Reagan

220:Notes

83:Upton

75:Irion

540:ISBN

521:ISBN

343:ISBN

321:ISBN

162:and

141:and

53:(1.6

27:The

35:of

590::

101:,

89:,

85:,

81:,

77:,

531:)

527:(

55:×

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.