251:

stone on the board is never a disadvantage in Y. Y is a complete and perfect information game in which no draw can be conceived, so there is a winning strategy for one player. The second player has no winning strategy so the first player has one. It is nevertheless possible for the first player to lose by making a sufficiently bad move, since although that stone has value, it may have significantly less value than the second move—an important consideration for understanding the nature of the pie rule.

168:

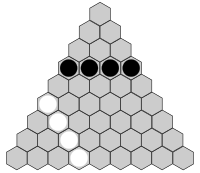

three "sides" (each 1/3 the circumference of the hemisphere), the distance from the "north pole" of the hemisphere to the equator was 1/4 the circumference, and thus the distance ratio improved from 1/3 to 3/4. This made defending a side from a center attack much more plausible. Thus the present "official" board is essentially a geodesic dome hemisphere squashed flat into a triangle to provide this effect.

125:

190:

77:

17:

250:

can be applied. It proves that the second player has no winning strategy. The argument is that if the second player had a winning strategy, then the first player could choose a random first move and then pretend that she is the second player and apply the strategy. An important point is that an extra

163:

Y's chief criticism is that on the standard hexagonal board a player controlling center can easily reach any edge no matter what the other player does. This is because the distance from the center to an edge is only approximately 1/3 the distance along the edge from corner to corner. As a result,

167:

Schensted and Titus attacked this problem with successive versions of the game board, culminating in the present "official" board with three pentagons inserted among the hexagons. They noted that were players to play on a hemisphere rather than a plane with hexagons, with the equator divided into

132:

Schensted and Titus argue that Y is a superior game to Hex because Hex can be seen as a subset of Y. Consider a board subdivided by a line of white and black pieces into three sections. The portion of the board at the bottom-right can then be considered a 5×5 Hex board, and played identically.

258:

In practice, assuming the pie rule is in force and the official

Schensted/Titus board is being used, Y is a very well balanced game giving essentially equal chances for any two players of equal strength. The balance is achieved because the first player will intentionally make a move that is

254:

If the "pie rule" is in force, however, the second player wins, because the second player can in principle evaluate whether or not the first move is a winning move and choose to invoke the pie rule if it is (thereby effectively becoming the first player).

66:

Y is typically played on a triangular board with hexagonal spaces; the "official" Y board has three points with five-connectivity instead of six-connectivity, but it is just as playable on a regular triangle. Schensted and Titus' book

159:

Y, like Hex, yields a strong first-player advantage. The standard approach to solving this difficulty is the "pie" rule: one player chooses where the first move will go and the other player then chooses who will be the first player.

259:

sufficiently "bad" that it is not clear to the second player whether it is a winning move or a losing move. It is up to the judgement of the second player to make this difficult determination and invoke the pie rule accordingly.

84:

As in most games of this type, one player takes the part of Black and one takes the part of White; they place stones on the board one at a time, neither removing nor moving any previously placed stones. The

133:

However, this sort of artificial construction on a Y board is extremely uncommon, and the games have different enough tactics (outside of constructed situations) to be considered separate, though related.

104:

Once a player connects all three sides of the board, the game ends and that player wins. The corners count as belonging to both sides of the board to which they are adjacent.

73:

has a large number of boards for play of Y, all hand-drawn; most of them seem irregular but turn out to be topologically identical to a regular Y board.

408:

58:, and others; it is also an early member in a long line of games Schensted has developed, each game more complex but also more generalized.

365:

233:

200:

176:

It has been formally shown that Y cannot end in a draw. That is, once the board is complete there must be one and only one winner.

413:

20:

A commercially-sold Y board, featuring three pentagonal points within the hex grid, representing half of a geodesic sphere

215:

247:

211:

108:

As in most connection games, the size of the board changes the nature of the game; small boards tend towards pure

418:

69:

291:

John F. Nash. Some games and machines for playing them. RAND Corporation Report D-1164, February 2, 1952.

28:

128:

Schensted and Titus argue that Y is a superior game to Hex because Hex can be seen as a subset of Y.

361:

144:

342:

268:

140:

47:

39:

273:

51:

43:

402:

393:

124:

292:

35:

389:

31:

109:

113:

86:

76:

384:

16:

38:

in the early 1950s. The game was independently invented in 1953 by

218:. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed.

148:

143:, the next game in the series of Y-related games; after that come

123:

75:

55:

15:

101:

Players take turns placing one stone of their color on the board.

183:

164:

defending an edge against a center attack is very difficult.

305:

Hexaflexagons, Probability

Paradoxes, and the Tower of Hanoi

207:

112:

play, whereas larger boards tend to make the game more

89:can be used to mitigate any first-move advantage.

293:https://www.rand.org/pubs/documents/D1164.html

8:

329:Craige Schensted. "A Bit of History". In

358:Hex Strategy: Making the Right Connections

234:Learn how and when to remove this message

42:and Charles Titus. It is a member of the

284:

370:Schensted, Craige and Titus, Charles.

333:(Game Manual). Kadon Enterprises Inc.

320:, Volume 4A. Addison-Wesley. Page 547.

307:. Cambridge University Press. Page 87.

7:

120:Relation to other connection games

14:

80:A simple board, 8 spaces per side

188:

318:The Art of Computer Programming

409:Board games introduced in 1953

1:

214:the claims made and adding

435:

248:strategy-stealing argument

97:The rules are as follows:

414:Abstract strategy games

372:Mudcrack Y & Poly-Y

303:Martin Gardner. 2008.

137:Mudcrack Y & Poly-Y

70:Mudcrack Y & Poly-Y

129:

81:

21:

343:Y Can't End in a Draw

180:The first player wins

127:

79:

34:, first described by

19:

316:Donald Knuth. 2011.

46:family inhabited by

199:possibly contains

130:

82:

22:

356:Browne, Cameron.

244:

243:

236:

201:original research

29:abstract strategy

426:

419:Connection games

345:

340:

334:

327:

321:

314:

308:

301:

295:

289:

274:Connection games

239:

232:

228:

225:

219:

216:inline citations

192:

191:

184:

40:Craige Schensted

434:

433:

429:

428:

427:

425:

424:

423:

399:

398:

381:

348:

341:

337:

328:

324:

315:

311:

302:

298:

290:

286:

282:

265:

240:

229:

223:

220:

205:

193:

189:

182:

174:

157:

139:also describes

122:

95:

64:

44:connection game

12:

11:

5:

432:

430:

422:

421:

416:

411:

401:

400:

397:

396:

387:

380:

379:External links

377:

376:

375:

368:

347:

346:

335:

322:

309:

296:

283:

281:

278:

277:

276:

271:

264:

261:

242:

241:

196:

194:

187:

181:

178:

173:

170:

156:

153:

121:

118:

106:

105:

102:

94:

91:

63:

60:

13:

10:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

431:

420:

417:

415:

412:

410:

407:

406:

404:

395:

394:BoardGameGeek

391:

390:The Game of Y

388:

386:

383:

382:

378:

373:

369:

367:

366:1-56881-117-9

363:

359:

355:

354:

353:

352:

344:

339:

336:

332:

331:The Game of Y

326:

323:

319:

313:

310:

306:

300:

297:

294:

288:

285:

279:

275:

272:

270:

267:

266:

262:

260:

256:

252:

249:

238:

235:

227:

217:

213:

209:

203:

202:

197:This section

195:

186:

185:

179:

177:

171:

169:

165:

161:

154:

152:

150:

146:

142:

138:

134:

126:

119:

117:

115:

111:

103:

100:

99:

98:

92:

90:

88:

78:

74:

72:

71:

61:

59:

57:

53:

49:

45:

41:

37:

33:

30:

26:

18:

385:Y on HexWiki

371:

357:

351:Bibliography

350:

349:

338:

330:

325:

317:

312:

304:

299:

287:

257:

253:

245:

230:

221:

198:

175:

166:

162:

158:

136:

135:

131:

107:

96:

83:

68:

65:

24:

23:

36:John Milnor

403:Categories

280:References

208:improve it

32:board game

246:In Y the

212:verifying

155:Criticism

114:strategic

263:See also

224:May 2014

172:No draws

110:tactical

87:pie rule

62:Gameplay

52:Havannah

206:Please

364:

141:Poly-Y

27:is an

149:*Star

93:Rules

56:TwixT

362:ISBN

147:and

145:Star

392:at

269:Hex

210:by

48:Hex

405::

360:.

151:.

116:.

54:,

50:,

374:.

237:)

231:(

226:)

222:(

204:.

25:Y

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.