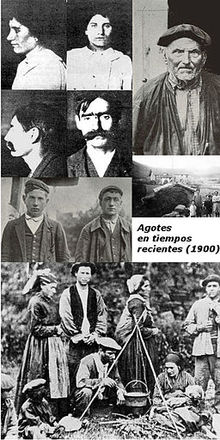

Cagots/Agotes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| Unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Spain (Basque Country and Navarre) and France (Nouvelle-Aquitaine and Occitania) | |

| Languages | |

| French, Occitan, Spanish, Basque | |

| Religion | |

| Predominately Roman Catholicism, with a minority Calvinism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Caquins, Cascarots, Occitans, Leonese |

The Cagots (pronounced [ka.ɡo]) were a persecuted minority who lived in the west of France and northern Spain: the Navarrese Pyrenees, Basque provinces, Béarn, Aragón, Gascony and Brittany. Evidence of the group exists as far back as 1000 CE. The name they were known by varied across the regions where they lived.

The origins of the Cagots remain uncertain, with various hypotheses proposed throughout history. Some theories suggest they were descendants of biblical or legendary figures cursed of God, or the descendants of medieval lepers, while others propose they were related to the Cathars or even a fallen guild of carpenters. Some suggest descent from a variety of other marginalized racial or religious groups. Despite the varied and often mythical explanations for their origins, the only consistent aspect of the Cagots was their societal exclusion and the lack of any distinct physical or cultural traits differentiating them from the general population.

The discriminatory treatment they faced included social segregation and restrictions on marriage and occupation. Despite laws and edicts from higher levels of government and religious authorities, this discrimination persisted into the 20th century.

Name

Etymology

The origins of both the term Cagots (and Agotes, Capots, Caqueux, etc.) and the Cagots themselves are uncertain. It has been suggested that they were descendants of the Visigoths defeated by Clovis I at the Battle of Vouillé, and that the name Cagot derives from caas ("dog") and the Old Occitan for Goth gòt around the 6th century. Yet in opposition to this etymology is the fact that the word cagot is first found in this form in 1542 in the works of François Rabelais. Seventeenth century French historian Pierre de Marca, in his Histoire de Béarn, propounds the reverse – that the word signifies "hunters of the Goths", and that the Cagots were descendants of the Saracens and Moors of Al-Andalus (or even Jews) after their defeat by Charles Martel, although this proposal was comprehensively refuted by the Prior of Livorno, Abbot Filippo Venuti [it] as early as 1754. Antoine Court de Gébelin derives the term cagot from the Latin caco-deus, caco meaning "false, bad, deceitful", and deus meaning "god", due to a belief that Cagots were descended from the Alans and followed Arianism.

Variations

Their name differed by province and the local language:

- In Gascony they were called Cagots, Cagous and Gafets

- In Bordeaux they were called Ladres, Cahets or Gahetz

- In the Spanish Basque country they were called Agotes, Agotak and Gafos

- In the French Basque Country the forms Agotac and Agoth were also used.

- In Anjou, Languedoc, and Armagnac they were called Capots, and Gens des Marais (marsh people)

- In Brittany they were called Cacons, Cacous (possibly from the Breton word Cacodd meaning leprous), Caquots and Cahets. They were also sometimes referred to as Kakouz, Caqueux, Caquets, Caquins, and Caquous, names of the local Caquins of Brittany due to similar low stature and discrimination in society.

- In Bigorre they were also called Graouès and Cascarots

- In Aunis, Poitou, and Saintonge they were also called Colliberts, a name taken from the former class of colliberts.

- Gésitains, or Gésites referencing Gehazi the servant of Elisha who was cursed with leprosy due to his greed. With the Parlement of Bordeaux [fr] recording descendants de la race de Giezy as an insult regularly used against Cagots. Giézitains is seen in the writings of Dominique Joseph Garat. Elizabeth Gaskell records the anglicised Gehazites in her work An Accursed Race.

- Other recorded names include Caffos, Essaurillés, Gaffots, Trangots, Caffets, Cailluands and Mézegs (most likely from the Old French mézeau meaning leper).

Previously some of these names had been viewed as being similar yet separate groups from the Cagots.

Origin

The origin of the Cagots is not known for certain, though through history many legends and hypotheses have been recorded providing potential origins and reasons for their ostracisation. The Cagots were not a distinct ethnic or religious group, but a racialised caste. They spoke the same language as the people in an area and generally kept the same religion as well, with later researchers remarking that there was no evidence to mark the Cagots as distinct from their neighbours. Their only distinguishing feature was their descent from families long identified as Cagots.

Biblical legends

Various legends placed the Cagots as originating from biblical events, including being descendants of the carpenters who made the cross that Jesus was crucified on, or being descendants of the bricklayers who built Solomon's Temple after being expelled from ancient Israel by God due to poor craftsmanship. Similarly a more detailed legend places the origins of the Cagots in Spain as being descendants of a Pyrenean master carver named Jacques, who traveled to ancient Israel via Tartessos, to cast Boaz and Jachin for Solomon's Temple. While in Israel he was distracted during the casting of Jachin by a woman, and due to the imperfection this caused in the column his descendants were cursed to suffer leprosy.

Religious origin

Another theory is that the Cagots were descendants of the Cathars, who had been persecuted for heresy in the Albigensian Crusade. With some comparisons including the use the term crestians to refer to Cagots, which evokes the name that the Cathars gave to themselves, bons crestians. A delegation by Cagots to Pope Leo X in 1514 made this claim, though the Cagots predate the Cathar heresy and the Cathar heresy was not present in Gascony and other regions where Cagots were present. The historian Daniel Hawkins suggests that perhaps this was a strategic move, as in the limpieza de sangre statutes such discrimination and persecution for those convicted of heresy expired after four generations and if this was the cause of their marginalisation, it also gave grounds for their emancipation. Others have suggested an origin as Arian Christians.

One of the earliest recorded mentions of Cagotes is in the charters of Navarre, developed around 1070. Another early mention of the Cagots is from 1288, when they appear to have been called Chretiens or Christianos. Other terms seen in use prior to the 16th century include Crestias, Chrestia, Crestiaa and Christianus, which in medieval texts became inseparable from the term leprosus, and so in Béarn became synonymous with the word leper. Thus, another theory is that the Cagots were early converts to Christianity, and that the hatred of their pagan neighbors continued after they also converted, merely for different reasons.

Medical origin

Another possible explanation of their name Chretiens or Christianos is to be found in the fact that in medieval times all lepers were known as pauperes Christi, and that, whether Visigoths or not, these Cagots were affected in the Middle Ages with a particular form of leprosy or a condition resembling it, such as psoriasis. Thus would arise the confusion between Christians and Cretins, and explain the similar restrictions placed on lepers and Cagots. Guy de Chauliac wrote in the 14th century, and Ambroise Paré wrote in 1561 of the Cagots being lepers with "beautiful faces" and skin with no signs of leprosy, describing them as "white lepers" (people afflicted with "white leprosy"). Later dermatologists believe that Paré was describing leucoderma. Early edicts apparently refer to lepers and Cagots as different categories of undesirables, With this distinction being explicit by 1593. The Parlement of Bordeaux and the Estates of Lower Navarre repeated customary prohibitions against them, with Bordeaux adding that when they were also lepers, if there still are any, they must carry clicquettes (rattles). One belief in Navarre were that the Agotes were descendants of French immigrant lepers to the region. Later English commentators supported the idea of an origin among a community of lepers due to the similarities in the treatment of Cagots in churches and the measures taken to allow lepers in England and Scotland to attend churches.

In the 1940s to 1950s blood type analysis was performed on the Cagots of Bozate [es] in Navarre. The blood type distribution showed more similarity with those observed in France among the French than those observed among the Basque. Pilar Hors uses this as support for the theory that the Cagots in Spain are descendants of French migrants, most likely from leper colonies.

Other origins

Victor de Rochas [fr] wrote that the Cagots were likely descendants of Spanish Roma from the Basque country.

In Bordeaux, where they were numerous, they were called ladres. This name has the same form as the Old French word ladre, meaning leper (ultimately derived from Latin Lazarus). It also has the same form as the Gascon word for thief (ultimately derived from Latin latrō, and cognate to the Catalan lladres and the Spanish ladrón meaning robber or looter), which is similar in meaning to the older, probably Celtic-origin Latin term bagaudae (or bagad), a possible origin of agote.

The alleged physical appearance and ethnicity of the Cagots varied wildly between legends and stories; some local legends (especially those that held to the leper theory) indicated that Cagots had blonde hair and blue eyes, while those favouring the Arab descent story said that Cagots were considerably darker. In Pío Baroja's work Las horas solitarias, he comments that Cagot residents of Bozate [es] had both individuals with "Germanic" features as well as individuals with "Romani" features, this is also supported by others who investigated the Cagots in the Basque Country, such as Philippe Veyrin [fr] who stated the "ethnic type" and names of Cagots were the same as the Basque within Navarre. Though people who set out to research the Cagots found them to be a diverse class of people in physical appearance, as diverse as the non-Cagot communities around them. One common trend was to claim that Cagots had no ears or no earlobes, or that one ear was longer than the other, with other supposed identifiers including webbed hands and/or feet, or the presence of goitres.

Graham Robb finds most of the above theories unlikely:

Nearly all the old and modern theories are unsatisfactory ... the real "mystery of the cagots" was the fact that they had no distinguishing features at all. They spoke whatever dialect was spoken in the region and their family names were not peculiar to the cagots ... The only real difference was that, after eight centuries of persecution, they tended to be more skillful and resourceful than the surrounding populations, and more likely to emigrate to America. They were feared because they were persecuted and might therefore seek revenge.

A modern hypothesis of interest is that the Cagots are the descendants of a fallen medieval guild of carpenters. This hypothesis would explain the most salient thing Cagots throughout France and Spain have in common: that is, being restricted in their choice of trade. The red webbed-foot symbol Cagots were sometimes forced to wear might have been the guild's original emblem, according to the hypothesis. There was a brief construction boom on the Way of St. James pilgrimage route in the 9th and 10th centuries; this could have brought the guild both power and suspicion. The collapse of their business would have left a scattered, yet cohesive group in the areas where Cagots are known.

Robb's guild hypothesis, alongside much of the work in his The Discovery of France, has been heavily criticised for " to understand most of the secondary works in his own bibliography" and being a "recycling of nineteenth-century myths".

For similar reasons due to their restricted trades, Delacampagne suggests a possible origin as a culturally distinct community of woodsmen who were Christianised relatively late.

Geography

Distribution

The cagots were present in France in Gascony to the Basque Country, but also in the north of Spain (in Aragon, south and north Navarre, and Asturias).

Cagots were typically required to live in separate quarters, these hamlets were called crestianies then from the 16th century cagoteries, which were often on the far outskirts of the villages. On the scale of Béarn, for example, the distribution of Cagots, often carpenters, was similar to that of other craftsmen, who were numerous mainly in the piedmont. Far from congregating in only a few places, the Cagots were scattered in over 137 villages and towns. Outside the mountains, 35 to 40% of communities had Cagots, especially the largest ones, excluding very small villages. The buildings making up the cagoteries are still present in many villages.

Toponomy

Toponymy and topography indicate that the places where the cagots were found have constant characteristics; these are gaps, generally across rivers or outside town walls, called "crestian" (and derivatives) or "place" (Laplace names are frequent) next to water points, places allocated to live and above all to practice their trades.

Toponymy also provides evidence of areas where Cagots had lived in the past. Various Street names are still in use such as Rue des cagots in the municipalities of Montgaillard and Lourdes, Impasse des cagots in Laurède, Place des cagots in Roquefort, Place des capots in Saint-Girons, and Rue des Capots in the municipalities of Mézin, Sos, Vic-Fezensac, Aire-sur-l'Adour, Eauze, and Gondrin.

In Aubiet, there is a locality called "les Mèstres". It was in this hamlet, that the cagots (Mèstres) of Aubiet lived, on the left bank of the Arrats, separated from the village by the river. In this last example, the discovery of the name of the place allowed teachers to discover the local history of the Cagots and to start educational work. Until the beginning of the 20th century, several districts of Cagots still bore the name of Charpentier ("Carpenter").

Treatment

Cagots were shunned and hated; while restrictions varied by time and place, with many discriminatory actions being codified into law in France in 1460, they were typically required to live in separate quarters. Cagots were excluded from various political and social rights.

Religious treatment

While Cagots followed the same religion as the non-Cagots who lived around them, they were subject to variety of discriminatory practices in religious rites and buildings, this included being forced to use a side entrance to churches, often an intentionally low one to force Cagots to bow and remind them of their subservient status. This practice, done for cultural rather than religious reasons, did not change even between Catholic and Huguenot areas, as shown by historian Raymond A. Mentzer, who records how even when Cagots converted from Catholicism to Calvinism they were still subject to the same discriminatory practices, including in religious rites and rituals. Cagots were expected to slip into churches quietly and congregate in the worst seats. They had their own holy water fonts set aside for Cagots, and touching the normal font was strictly forbidden. These restrictions were taken seriously; with one story collected by Elizabeth Gaskell explaining the origin of the skeleton of a hand nailed to the church door in Quimperlé, Brittany, where in the 18th century, a wealthy Cagot had his hand cut off and nailed to the church door for daring to touch the font reserved for "clean" citizens.

Treatment by governments

Cagots were not allowed to marry non-Cagots leading to forced endogamy, though in some areas in the later centuries (such as Béarn) they were able to marry non-Cagots though the non-Cagot would then be classed as a Cagot. They were not allowed to enter taverns or use public fountains. The marginalization of the Cagots began at baptism where chimes were not rung in celebration as was the case for non-Cagots and that the baptisms were held at nightfall. Within parish registries the term cagot, or its scholarly synonym gezitan, was entered. Cagots were buried in cemeteries separate from non-Cagots with reports of riots occurring if bishops tried to have the bodies moved to non-Cagot cemeteries. Commonly Cagots were not given a standard last name in registries and records but were only listed by their first name, followed by the mention "crestians" or "cagot", such as on their baptismal certificate, They were allowed to enter a church only by a special door and, during the service, a rail separated them from the other worshippers. They were forbidden from joining the priesthood. Either they were altogether forbidden to partake of the sacrament, or the Eucharist was given to them on the end of a wooden spoon, while a holy water stoup was reserved for their exclusive use. They were compelled to wear a distinctive dress to which, in some places, was attached the foot of a goose or duck (whence they were sometimes called Canards), and latterly to have a red representation of a goose's foot in fabric sewn onto their clothes. Whilst in Navarre a court ruling in 1623 required all Cagots to wear cloaks with a yellow trim to identify them as Cagots.

In Spanish territories Cagots were subject to the limpieza de sangre statutes (cleanliness of blood). These statutes established the legal discrimination, restriction of rights, and restriction of privileges of the descendants of Muslims, Jews, Romani, and Cagots.

Work

Cagots were prohibited from selling food or wine, touching food in the market, working with livestock, or entering mills. The Cagots were often restricted to craft trades including those of carpenter, masons, woodcutters, wood carvers, coopers, butcher, and rope-maker. They were also often employed as musicians in Navarre. Cagots who were involved in masonry and carpentry were often contracted to construct major public buildings, such as churches, an example being the Protestant temple of Pau [fr]. Due to association with woodworking crafts, Cagots often worked as the operators of instruments of torture and execution, as well as making the instruments themselves. Such professions may have perpetuated their social ostracisation.

Cagot women were often midwives until the 15th century. Due to social exclusion, in France the Cagots were exempt from taxation until the 18th century. By the 19th century these restrictions seem to have been lifted, but the trades continued to be practiced by Cagots, along with other trades such as weaving and blacksmithing. Because the main identifying mark of the Cagots was the restriction of their trades to a few small options, their segregation has been compared to the caste system in India, with the Cagots being compared to the Dalits.

Accusations and pseudo-medical beliefs

Few consistent reasons were given as to why Cagots were hated; accusations varied from them being cretins, lepers, heretics, cannibals, sorcerers, werewolves, sexual deviants, to actions they were accused of such as poisoning wells, or for simply being intrinsically evil. They were viewed as untouchables, with Christian Delacampagne [fr] noting how it was believed that they could cause children to fall ill by touching them or even just looking at them, being considered so pestilential that it was a crime for them to walk common roads barefooted or to drink from the same cup as non-Cagots. It was also a common belief that the Cagots gave off a foul smell. Joaquim de Santa Rosa de Viterbo [pt] recorded that many believed Cagots were born with a tail. Many Bretons believed that Cagots bled from their navel on Good Friday.

The French early psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol wrote in his 1838 works that the Cagots were a subset of "idiot", and separate from "cretins". By the middle of the 19th century, previous pseudo-medical beliefs and beliefs of them being intellectually inferior had waned and German doctors, by 1849, regarded them as “not without the ability to become useful members of society.” Though various French and British doctors were continuing to label the Cagots as a race inherently afflicted with congenital disabilities to the end of the 19th century. Daniel Tuke wrote in 1880 after visiting communities where Cagots lived, noted how local people would not subject "cretins" born to non-Cagots to living with Cagots.

The Cagots did have a culture of their own, but very little of it was written down or preserved; as a result, almost everything that is known about them relates to their persecution. The repression lasted through the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Industrial Revolution, with the prejudice fading only in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Cagot as pejorative

Philosopher Jacob Rogozinski [fr] highlights how even from as far back as the work of François Rabelais in the 16th century, the term cagot was used as a synonym for people viewed as deceitful and hypocritical. In contemporary language the term cagot has been further separated from it being the name of a distinct caste of people to being a pejorative term for any person who is "lazy" or "shameful". Similar transformations have occurred with the Spanish equivalent name agote.

Cagot allies

An appeal by the Cagots to Pope Leo X in 1514 was successful, and he published a papal bull in 1515, instructing that the Cagots be treated "with kindness, in the same way as the other believers." Still, little changed, as most local authorities ignored the bull.

The nominal though usually ineffective allies of the Cagots were the government, the educated, and the wealthy. This included Charles V who officially supported tolerance of and improvements to the lives of Cagots. It has been suggested that the odd patchwork of areas which recognized Cagots has more to do with which local governments tolerated the prejudice, and which allowed Cagots to be a normal part of society. In a study in 1683, doctors examined the Cagots and found them no different from normal citizens. Notably, they did not actually suffer from leprosy or any other disease that could clarify their exclusion from society. The parlements of Pau, Toulouse and Bordeaux were informed of the situation, and money was allocated to improve the situation of the Cagots, but the populace and local authorities resisted.

Through many of the centuries Cagots in France and Spain came under the protection and jurisdiction of the church. In 1673, the Ursúa lords of the municipality of Baztán advocated the recognition of the local Cagots as natural residents of the Baztán. Also in the 17th century Jean-Baptiste Colbert officially freed Cagots in France from their servitude to parish churches and from restrictions placed upon them, though in practicality nothing changed.

By the 18th century Cagots made up considerable portions of various settlements, such as in Baigorri where Cagots made up 10% of the population.

In 1709, the influential politician Juan de Goyeneche [es] planned and constructed the manufacturing town of Nuevo Baztán (after his native Baztan Valley in Navarre) near Madrid. He brought many Cagot settlers to Nuevo Baztán, but after some years, many returned to Navarre, unhappy with their work conditions.

In 1723 the Parlement of Bordeaux instituted a fine of 500 French livres for anyone insulting any individual as "alleged descendants of the Giezy race, and treating them as agots, cagots, gahets or ladres"; ordering that they will be admitted to general and particular assemblies, to municipal offices and honors of the church, they may even be placed in the galleries and other places of the said church where they will be treated and recognized as the other inhabitants of the places, without any distinction; as also that their children will be received in the schools and colleges of the cities, towns and villages, and will be admitted in all the Christian instructions indiscriminately.

During the French Revolution substantive steps were taken to end discrimination toward Cagots. Revolutionary authorities claimed that Cagots were no different from other citizens, and de jure discrimination generally came to an end. And while their treatment did improve compared to previous centuries, local prejudice from the non-Cagot populace persisted, though the practice began to decline. Also, during the revolution, Cagots stormed record offices and burned birth certificates in an attempt to conceal their heritage. These measures did not prove effective, as the local populace still remembered. Rhyming songs kept the names of Cagot families known.

Modern status

Kurt Tucholsky wrote in his book on the Pyrenees in 1927: "There were many in the Argelès valley, near Luchon and in the Ariège district. Today they are almost extinct, you have to search hard if you want to see them". Examples of prejudice still occurred into the 19th and 20th century, including a scandal in the village of Lescun where in the 1950s a non-Cagot woman married a Cagot man.

There was a distinct Cagot community in Navarre until the early 20th century, with the small northern village called Arizkun in Basque (or Arizcun in Spanish) being the last haven of this segregation, where the community was contained within the neighbourhood of Bozate. Between 1915 and 1920 the Ursúa noble family sold the land that Cagots had worked for the Ursúa for centuries in the area of Baztan to the Cagot families. Family names in Spain still associated with having Cagot ancestors include: Bidegain, Errotaberea, Zaldua, Maistruarena, Amorena, and Santxotena.

The Cagots no longer form a separate social class and were largely assimilated into the general population. Very little of Cagot culture still exists, as most descendants of Cagots have preferred not to be known as such.

There are two museums dedicated to the history of the Cagots, one in the neighborhood of Bozate in the town of Arizkun, Spain, the Museo Etnográfico de los Agotes (Ethnographic Museum of the Agotes), opened by the sculptor and Cagot, Xabier Santxotena [eu] in 2003, and a museum in the Château des Nestes in Arreau, France.

In 2021 and 2022 anti-vaccination and anti-vaccine passport protestors in France started wearing the red goose's foot symbol that Cagots were forced to wear, and handed out cards explaining the discrimination against the Cagots.

In media

References to Cagots as well as Cagots as characters have appeared in works throughout the past millennia. One of the earliest examples is the legend of the battle of 1373 that led to The Tribute of the Three Cows, the people of the French Valley of Barétous [fr] are said to have been led by a Cagot with four ears. References to Cagots occur semi-regularly in French literary works such as in the 1793 French play Le jugement dernier des rois, by Sylvain Maréchal. The liberated subjects of the kings of Europe provide critiques of and insult their former rulers, where they say the Spanish king has "stupidity, cagotism and despotism imprinted on his royal face". Multiple references to Cagots have appeared in the poems of the 19th century French poet Édouard Pailleron. Multiple travellers to the Pyrenees upon learning about and seeing the Cagots were inspired to write of their conditions both in fictional and non-fictional works. Such travellers included the Irish author and diplomat Thomas Colley Grattan, whose 1823 story The Cagot's Hut details the otherness he perceived in the Cagots during his travels in the French Pyrenees, detailing many of the mythical features that became folklore about the Cagots appearance. In July 1841 the German poet Heinrich Heine visited the town of Cauterets and learned of the Cagots and their discrimination by others, subsequently becoming the topic of his poem Canto XV in Atta Troll. After travelling in southern France in 1853, Elizabeth Gaskell published her non-fiction work An Accursed Race, detailing the contemporary condition of the Cagots.

More recently, the Basque director Iñaki Elizalde [eu] released a Spanish-language film titled Baztan in 2012. The film deals with a young man fighting against the discrimination he and his family have suffered for centuries due to being Cagots. There are several references to the history and persecution of the Cagots in Rachel Kushner’s novel Creation Lake.

Cagotic architecture

-

Sculpture of a "Cagot" in the Église Saint-Girons in Monein, which was built by the local cagot craftsmen in 1464.

-

Cagot houses in the Mailhòc district (wooden mallet), Saint-Savin, 1906.

-

Halle de Campan [fr] which was built by the local Cagots.

-

The interior of Halle de Campan.

-

Montaner castle, built by the Cagots, for Gaston III, Count of Foix.

-

The rue des capots, and the "porte anglaise" in Mézin, Lot-et-Garonne. The rue des capots was formerly inhabited by the Capots (Cagots) of the town.

Fonts

-

Font for Cagots in the church of Bassoues, dating from the 15th century.

-

Font for Cagots in the Église Saint-Girons in Monein, with a small sculpture of what is presumed to be a Cagot.

Doors

-

Door of the Cagots of the church of Sauveterre-de-Béarn.

-

Former door for Cagots in Bahus-Soubiran at the Church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste.

-

Door of the Cagots in La Bastide-Clairence at the Church of Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption.

-

Door for Cagots in the Church of Saint-Aubin in Saint-Aubin, Landes.

See also

- Caquins of Brittany, a derogatory term used to describe coopers and ropemakers.

- Cascarots, an ethnic group in the Spanish Basque country and the French Basque coast possibly related to the Cagots.

- Gitanos, an ethnic minority in Spain and Portugal.

- Maragato [es], an ethnic group in Spain who were also discriminated against and have unknown origins.

- Vaqueiros de alzada, a discriminated group of cowherders in Northern Spain.

- Xueta, a persecuted ethnic minority in Mallorca, often referenced in works discussing the persecution of Cagots in Spain.

Notes

- See Name Variations

- The colliberts were not restricted to the western coast of France, and were also found through the Alps and into Italy. In France records also use the names: colliberti, culvert, cuvert, cuilvert, culvert.

References

- ^ Hansson (1996).

- ^ Viterbo, Joaquim de Santa Rosa de (1856). Elucidário das palavras, termos e frases que em Portugal antigamente se usaram e que hoje regularmente se ignoram [Elucidation of the words, terms and phrases that were used in Portugal in the past and that today are regularly ignored] (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Lisbon: A. J. Fernandes Lopes. p. 64 – via Google Books.

Certas Famílias em os Reinos de Aragão, e Navarra, e Principado de Bearne, descendentes dos Godos, que sem mais culpa, que tyrannizarem os seus Maiores antigamente aquellas Provincias, são tratados com o maior desprezo, e abatimento, assim nas materias civís, como de Religião: e até dizem delles, que nascem com rabo.

[Certain Families in the Kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre, and the Principality of Bearne, descendants of the Goths, who without more guilt than their leaders formerly tyrannizing those Provinces, are treated with the greatest contempt and abasement, in civil matters as well as in Religion: and they even say that they are born with tails.] - ^ Garat, Dominique Joseph (1869). Origines Des Basques De France Et D'espagne [Origins of the Basques of France and Spain] (in French).

- ^ von Zach (1798), pp. 522–523: "4) Welches wäre nun dasjenige Volk, welches nach seiner Unterjochung nur in diesen Elenden vorhande wäre? In keinem stücke sind die Meinungen der Schriftsteller so-sehr getheilt. Einige halten sie für die Abkömmlinge der von den Römern und späterhin von den Franken unterjochen ersten Bewohner - der Gallier. Court de Gebelin in seinem Monde primitif wählt die Alanen und führt die Schlacht vom Jahr 463 an, in welcher diese mit den Visigothen überwunden wurden. Marca betrachtet sie als Überreste der von Carl Martel unter Anführung des Abdalrahman besiegten Sarazanen. Ramond in seiner Reise nach den Pyrenäen leitet sie von den Arianisch gesinnten Völkern ab, welcher unter dem Clodoveus im Jahr 507 bey Vouglé (in Campo oder Campania Vocladensi) unter der Anführung Alarichs zehn Meilen von Poitiers geschlagen, zerstreut, misshandelt, und von den Bewohnern der Loire und der Sévre mit gleicher Erbitterung und Verachtung gegen die Mündungen dieser beyden Flüsse getrieben wurden. Wer hier Recht hat, muss erst in der Folge entschieden, und ehe diess geschehen kann, die Sache noch genauer untersucht werden."

- Michel (1847), pp. 21–22, 284; Álvarez (2019); Erroll (1899); Delacampagne (1983), p. 125–127; Donkin & Diez (1864), p. 107: "called canes Gothi, cagots (Pr. câ a dog, and Got = Goth)."; von Zach (1798), p. 520: "Die erste und natürlichste Frage entsteht über den Namen. Woher die sonderbare Benennung Cagot? Scaliger's Meinung, welcher sie von Caas Goth, Canis Gothus ableitet, scheint ihren Gothischen Ursprung, welcher doch erst bewiesen werden sollte, als ausgemacht voraus zu setzen, auch scheint diese Ableitung zu künstlich und erzwungen zu seyn."

- Demonet (2021), pp. 403–413.

- ^ Chisholm (1911), p. 947.

- ^ Fayanás Escuer, Edmundo (26 March 2018). "Un pueblo maldito: los agotes de Navarra" [A cursed town: the agotes of Navarra]. Neuva Tribuna (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ British Medical Journal (1912).

- Heng (2022), p. 31–32.

- Larronde, Claude (1998). Vic-Bigorre et son patrimoine [Vic-Bigorre and its heritage] (in French). Société académique des Hautes-Pyrénées.

Il s'agit de descendants de Sarrasins qui restèrent en Gascogne après que Charles Martel eut défait Abdel-Rahman. Ils se convertirent et devinrent chrétiens.

[They are descendants of Saracens who remained in Gascony after Charles Martel had defeated Abdel-Rahman. They converted and became Christians.] - ^ Álvarez (2019).

- Hawkins (2014), p. 37.

- Venuti, Filippo (1754). Dissertations sur les anciens monumens de la ville de Bordeaux, sur les Gahets, les antiquités, et les ducs d'Aquitaine avec un traité historique sur les monoyes que les anglais ont frappées dans cette province, etc [Dissertations on the ancient monuments of the city of Bordeaux, on the Gahets (Cagots), antiquities, and the Dukes of Aquitaine with a historical treatise on the monoyes that the English struck in this province, etc.] (in French). Bordeaux. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023 – via University of Cologne.

- ^ Gébelin (1842), pp. 1182–1183.

- ^ Hawkins (2014), p. 2.

- ^ Lascorz, N. Lucía Dueso ; d'o Río Martínez, Bizén (1992). "Los agotes de Gestavi (bal de Gistau)" [The Agotes of Gestavi (Gistau Valley)]. Argensola: Revista de Ciencias Sociales del Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses (in Spanish). 106. Huesca: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses: 151–172. ISSN 0518-4088. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 376, 382.

- ^ Louis-Lande (1878), p. 429: "Les gafets ou gahets de Guyenne font leur apparition dans l'histoire vers la fin du XIIIe siècle, en même temps que les cagots. Eux aussi étaient tenus pour ladres; ils avaient à l'église une porte, une place et un bénitier réservés, et ils étaient enterrés séparément. La coutume du Mas-d'Agenais, rédigée en 1388, défend à quiconque « d'acheter, pour les vendre, bétail ou volaille de gafet ou de gafete, ni de louer gafet ou gafete pour vendanger. » La coutume de Marmande défend aux gafets d'aller pieds nus par les rues et sans un « signal » de drap rouge appliqué sur le côté, gauche de la robe, d'acheter ni de séjourner dans la ville un autre jour que le lundi; elle leur enjoint, s'ils rencontrent homme ou femme, de se mettre à l'écart autant que possible jusqu'à ce que le passant se soit éloigné."

- ^ von Zach (1798), pp. 516–517: "Man kennt sie in Bretagne unter der Benennung von Cacous oder Caqueux. Man findet sie in Aunis, vorzüglich auf der Insel Maillezais, so wie auch in La Rochelle, wo sie Coliberts gennent werden. In Guyenne und Gascogne in der Nähe von Bordeaux erscheinen sie unter dem Namen der Cahets, und halten sich in den unbewohnbarsten Morästen, Sümpfen und Heiden auf. In den beyden Navarren heissen sie Caffos, Cagotes, Agotes."

- ^ Veyrin (2011), p. 84.

- Hawkins (2014), p. 2; Hansson (1996); Tuke (1880), p. 376

- Loubès (1995); Hansson (1996); Antolini (1995); Hawkins (2014), p. 2

- ^ Winkle (1997), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Fastiggi, Robert L.; Koterski, Joseph W.; Coppa, Frank J., eds. (2010). "Cagots". New Catholic Encyclopedia Supplement. Vol. 1. Cengage Gale. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1414475882.

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 376.

- Lagneau, Gustave Simon (1870). Cagots (in French). Paris: Victor Masson et Fils. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021.

- Tuke (1880), pp. 376, 379–380.

- Michel (1847), pp. 56–58.

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 381.

- ^ Rogozinski (2024), pp. 205–206.

- ^ von Zach (1798), pp. 521: "Es fragt sich 2) gehören die Caquets oder Caqueux in Bretagne und die Cagots in Bearn, so wie Cassos in Navarra zu einem und demselben Geschlechte? Wir glauben die Frage mit Ramond bejahen zu können. Die grosse Verwandtschaft der Namen, die Ähnlichkeit ihres Zustandes, die aller Orten gleiche Verachtung, und derselbe Geist, der aus allen Verordnungen in Betreff ihrer herverleuchtet scheinen diess zu beweisen."

- ^ Veyrin (2011), p. 87.

- Bloch, Marc (1975). "The "Colliberti." A Study on the Formation of the Servile Class". Slavery and Serfdom in the Middle Ages. Translated by Beer, WilliamR. University of California Press. pp. 93–150. ISBN 978-0520017672.

- ^ Garcia Piñuela, M. (2012). "Etnia marginada, Los Agotes" [Marginalized ethnic group, the Agotes]. Mitologia (in Spanish). pp. 12–13. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023.

- ^ Gaskell (1855).

- Michel (1847), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Erroll (1899).

- Hors (1951), p. 308.

- Garate (1958), p. 521.

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 382.

- Michel (1847), pp. 166–170.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1978). The Albigensian Crusade. Faber and Faber. p. 237. ISBN 0-571-20002-8.

- Scheutz, Staffan (December 2018). "Beyond thought - the Cagots of France". La Piccioletta Barca. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020.

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 377.

- ^ Michel (1847), p. 5.

- ^ Carrasco, Bel (27 April 1979). "Los agotes, minoría, étnica española: Mesa redonda de la Asociación Madrileña de Antropología" [The agotes, Spanish ethnic minority: Round table of the Madrid Anthropology Association]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Roberts, Susanne F. (October 1993). "Des Lépreux aux Cagots: Recherches sur les Sociétés Marginales en Aquitaine Médiévale. by Françoise Bériac". Speculum. 68 (4): 1063–1065. doi:10.2307/2865504. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2865504.

- Lafont, R.; Duvernoy, J.; Roquebert, M.; Labal, P. (1982). Fayard (ed.). Les Cathares en Occitanie [The Cathars in Occitania] (in French). p. 7.

- ^ Robb (2007), p. 45.

- Hudry-Menos, Grégoire (1868). "L'Israël des Alpes ou les Vaudois du Piémont. — II. — La Croisade albigeoise et la dispersion" [The Israel of the Alps or the Vaudois of Piedmont. - II. - The Albigensian Crusade and the dispersion]. Revue des Deux Mondes (in French). Vol. 74. p. 588. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Hawkins (2014), p. 36.

- ^ Veyrin (2011), p. 85.

- Hors (1951), p. 316.

- "Cagot: Etymologie de Cagot" [Cagot: Etymology of Cagot]. Centre national de ressources textuelles et lexicales (in French). Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Louis-Lande (1878), p. 448: "La leucé attaque moins profondément l'organisme, et c'est elle que les médecins du moyen âge attribuent particulièrement aux caquots, capots et cagots, qu'ils appellent de son nom ladres blancs. Les caractères principaux en sont, suivant Guy de Chauliac, vieil auteur du XIVe siècle: « une certaine couleur vilaine qui saute aux yeux, la morphée ou teinte blafarde de la peau, etc. »"

- ^ Barzilay, Tzafrir (2022). Poisoned Wells: Accusations, Persecution, and Minorities in Medieval Europe, 1321-1422. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780812298222 – via Google Books.

- Hawkins (2014), p. 12.

- Tuke (1880), p. 384.

- Hors (1951), pp. 335–336.

- de Rochas, Victor (1876). Les Parias de France et d'Espagne (cagots et bohémiens) [The Parias of France and Spain (cagots and bohemians)] (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ da Silva (2006).

- Baroja, Pío (1982). Las horas solitarias [The lonely hours] (in Spanish). Caro Raggio Editor S.L. ISBN 9788470350665.

Cara ancha y juanetuda, esqueleto fuerte, pómulos salientes, distancia bicigomática fuerte, grandes ojos azules o verdes claros, algo oblicuos. Cráneo braquicéfalo, tez blanca, pálida y pelo castaño o rubio; no se parece en nada al vasco clásico. Es un tipo centro europeo o del norte. Hay viejos en Bozate que parecen retratos de Durero, de aire germánico. También hay otros de cara más alargada y morena que recuerdan al gitano.

[Wide, bunion face, strong skeleton, prominent cheekbones, strong bizygomatic distance, large blue or light green eyes, somewhat oblique. Brachycephalic skull, white, pale complexion and brown or blonde hair; It doesn't look anything like classic Basque. It is a central European or northern type. There are old men in Bozate who look like portraits of Dürer, with a Germanic air. There are also others with a longer and darker face that are reminiscent of the gypsy.] - Huici (1984), p. 19: "Webster rechaza la idea de que los agotes fueran un pueblo distinto del vasco, por razones lingüísticas. Según el sabio Inglés un pueblo, extranjero, que vive aislado de la sociedad que le rodea y con barreras severísimas, no ha podido olvidar totalmente su lengua ancestral. Los agotes, sin embargo, hablan el vascuence exactamente Igual que los vascos que les rodean."

- Roussel (1893), p. 149: "M. Roussel persiste à voir des descendants blonds des Goths dans les Cagots des Pyrénées. Mais ils sont en réalité très diversifiés plus souvent bruns que blonds, brachy et dolichocéphales, semblables au fond de la population où ils vivent; ls parlent la langue ou le patois du pays."

- ^ Tuke (1880), p. 379.

- Fabre, Michel (1987). Le Mystère des Cagots, race maudite des Pyrénées [The Mystery of the Cagots, cursed race of the Pyrenees] (in French). MCT. ISBN 2905521619.

- ^ Cabarrouy (1995).

- Michel (1847), pp. 50–51.

- ^ Thomas (2008).

- ^ Robb (2007), p. 46.

- Bell, David A. (13 February 2008). "Bicycle History". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Delacampagne (1983), p. 137–138.

- Antolini (1995).

- ^ Jolly (2000), p. 200: "Dans toutes les localités où les cagots étaient présents, un quartier d'habitation, dont le nom diffère pour chaque village, leur était réservé. Ce quartier est généralement situé aux marges de l'habitat et n'est pas en continuité directe avec le reste du village Quand les cagots accédaient au foncier, c'était d'abord sur les marges du terroir cultivé, à la limite du communal, sur les terrains les moins propices à l'agriculture.

- Michel (1847), p. 96.

- ^ Bériac (1987).

- Veyrin (2011), pp. 85–86.

- Tuke (1880), p. 378.

- "Les cagots à Campan" [The Cagots in Campan]. Lieux et légendes dans les Hautes-Pyrénées (in French). Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- Tuke (1880), pp. 377–378.

- "Les cagots à Montgaillard: et dans les Hautes-Pyrénées" [The Cagots in Montgaillard: and in the Hautes-Pyrénées]. Lieux et légendes dans les Hautes-Pyrénées (in French). Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Les cagots à Lourdes" [The Cagots in Lourdes]. Lieux et légendes dans les Hautes-Pyrénées (in French). Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- "Vic-Fezensac. La visite du quartier des Capots attise la curiosité des Vicois" [Vic-Fezensac. A visit to the Capots district arouses the curiosity of the people of Vicois]. La Depeche (in French). 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- "Les cagots d'Aubiet et ceux du Gers" [The Cagots of Aubiet and those of the Gers]. OCCE (in French). Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- von Zach (1798), pp. 519–520: "dass sie im J. 1460 der Gegenstand einer Beschwerde der Bearner Landstände waren, welche verlangten, dass man ihnen wegen zu besorgender Ansteckung verbiete, mit blossen Füssen zu gehen, unter Bedrohung der Strafe, dass ihnen im Betretungsfalle die Füsse mit einem Eisen sollten durchschlagen werden. Auch drangen die Stände darauf, dass sie auf ihren Kleidern ihr ehemahliges unterscheidendes Merkmahl, den Gänse - oder Aenten - Fuss fernerhin tragen sollten."

- Loubès (1995); Álvarez (2019); Kessel (2019); Guerreau & Guy (1988); Guy (1983)

- ^ "Agote: etnología e historia" [Agote: ethnology and history]. Euskomedia: Auñamendi Entziklopedia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 May 2011.

- Mentzer, Raymond A. (1996). "The Persistence of "Superstition and Idolatry" among Rural French Calvinists". Church History. 65 (2): 220–233 . doi:10.2307/3170289. JSTOR 3170289.

- Leclercq, H. (1910). "Holy Water Fonts". CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Holy Water Fonts. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023.

- Robb (2007), p. 44.

- Loubès (1995); Veyrin (2011), p. 84; Álvarez (2019); Kessel (2019); Rogozinski (2024), pp. 205–206

- Jolly (2000), p. 205: "L'étendue des aires matrimoniales et la distribution des patronymes constituent les principaux indices de la mobilité des cagots. F. Bériac relie l'extension des aires matrimoniales des cagots des différentes localités étudiées (de 20 à plus de 35 km) à l'importance et la densité relative des groupes de cagots, corrélant la recherche de conjoints lointains à l'épuisement des possibilités locales. A. Guerreau et Y. Guy, en utilisant la documentation gersoise exploitée par G. Loubès et les documents publiés par Fay pour le Béarn et la Chalosse (XVe–XVIIe s.) concluent que l'endogamie des cagots semble s'opérer au sein de trois sous-ensembles qui correspondent à ceux que distingue la terminologie à partir du XVIe siècle: agotes, cagots, capots. Au sein de chacun d'eux, les distances moyennes d'intermariage sont relativement importantes: entre 12 et 15 km en Béarn et Chalosse, plus de 30 km dans le Gers, dans une société où plus de la moitié des mariages se faisaient à l'intérieur d'un même village."

- ^ Guerreau & Guy (1988).

- ^ Kessel (2019).

- Guy (1983); Winkle (1997), pp. 39–40; Tuke (1880), p. 376; Heng (2022), p. 31–32

- Louis-Lande (1878), p. 430.

- ^ Duffy, Diane (7 August 2019). "This Month in Writing: 'An Accursed Race'". The Gaskell Society. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ von Zach (1798), p. 519: "dass sie in die Kirchen nicht anders, als durch abgesonderte Thüren hineintreten durften, und in diesen ihre eigenen Weihbecken und Stühle für sich und ihre Familie hatten."

- del Carmen Aguirre Delclaux (2008).

- Ulysse (1891); Álvarez (2019); del Carmen Aguirre Delclaux (2008); Louis-Lande (1878), p. 426: "Aussi les tenait-on prudemment à l'écart: ceux des villes étaient relégués dans un faubourg spécial où les personnes saines se lussent bien gardées de mettre les pieds et d'où ils ne pouvaient sortir eux-mêmes sans porter sur leur vêtement et bien en évidence un morceau de drap rouge taillé en patte d'oie ou de canard"

- Hors (1951), p. 311.

- Llinares, Lidia Montesinos (2013). IRALIKU'K: La confrontación de los comunales: Etnografía e historia de las relaciones de propiedad en Goizueta [IRALIKU'K: The confrontation of the communal: Ethnography and history of property relations in Goizueta] (MA) (in Spanish). p. 81.

- ^ "Los agotes en Navarra, el pueblo maldito amante de la artesanía" [The Agotes in Navarra, the cursed town that loves crafts] (in Spanish). 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Pérez (2010).

- Hawkins (2014), p. 6.

- Loubès (1995).

- Guy (1983).

- ^ Jolly (2000), p. 200: "Lors des entretiens effectués récemment par P. Antolini dans le village d'Arizcun en Navarre, il ressort que les cagots dans cette région avaient des métiers et peu de terres: charpentier, menuisier, forgeron, carrier, meunier, joueur de flûte et de tambour, chasseur, tisserand. Ils travaillaient aussi sur les terres du seigneur Ursua comme métayers, ou comme ouvriers pour les agriculteurs et leveurs du village. Vers 1915-1920, la maison Ursua vendit aux cagots les terres qu'ils travaillaient: ils sont à présent presque tous propriétaires de leurs maisons et de leurs terres, mais la majorité sont encore artisans."

- von Zach (1798), pp. 516–517: "Ausser dem Holzspalten und Zimmern sey ihnen kein anderes Handwerk erlaubt: diese beyden Beschäftigungen seyen aber eben dadurch verächtlich und ehrlos geworden."

- ^ Delacampagne (1983), p. 114–115, 124.

- Arnold-Baker, Charles (2001). The Companion to British History (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 219. ISBN 0-203-93013-4.

- Fay, Henri-Marcel (1910). Histoire de la lèpre en France. I. Lépreux et cagots du Sud-Ouest, notes historiques, médicales, philologiques, suivies de documents [History of leprosy in France. I. lepers and cagots in southwestern, medical and historical, philological, followed by documents] (in French). Paris: H. Champion. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023.

- Michel (1847), p. 185.

- Tuke (1880), p. 378–379.

- von Zach (1798), p. 515: "An der westlichen Küste dieses Landes, von St. Malo an, bis tief die Pyrenäen hinauf, befindet sich eine Classe von Manschen, welche den Indischen Parias sehr nahe kommt, und mit diesen auf gleicher Stufe der Erniedrigung steht. Sie leben in diesen Gegenden zerstreut, seit undenklichen Zeiten bis auf den heutigen Tag unter fortdauernder Herabwürdigung von Seiten ihrer mehr begünstigten Mitbürger. Sie heissen mit ihrer bekanntesten und allgemeinsten Benennung Cagots, und es bleibt zweifelhaft, ob die Heuchler ihnen, oder sie diesen ihren Namen mitgetheilt haben, obgleich das letzte mir glaublicher scheint."

- da Silva (2006), pp. 21–22.

- Tuke (1880), p. 380.

- ^ Delacampagne (1983), p. 114–115, 121–124.

- Pigeaud, Jackie (2000). "Le Pongo, l'idiot et le cagot. Quelques remarques sur la définition de l'Autre" [The Pongo, the idiot and the cagot. Some remarks on the definition of the Other]. Études littéraires [fr] (in French). 32 (1–2): 243–262. doi:10.7202/501270ar. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- Rheinische Monatsschrift für Praktische Aerzte [Rheinische monthly publication for practical doctors] (in German). Vol. 3. 1849. p. 288.

- Simms, Norman (1993). "The Cagots of Southwestern France: A Study in Structural Discrimination". Mentalities. 8 (1): 44–.

- "Tesoro de los diccionarios históricos de la lengua Española - Agote" [Treasure trove of historical dictionaries of the Spanish language - Agote]. Real Academia Española (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 May 2024.

- da Silva (2006); Loubès (1995); Pérez (2010); British Medical Journal (1912); Jolly (2000), p. 202; Veyrin (2011), p. 84

- Hors (1951), pp. 310–311.

- Michel (1847), pp. 189–192.

- Rivière-Chalan (1978), p. 7.

- Hors (1951), pp. 323–324.

- Michel (1847), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Archives départementales de la Gironde (ed.). "Inventaire des archives de la série C" [Inventory of the C-series archives]. archives.gironde.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "Die Cagots in Frankreich: (Schluß des Artikels in voriger Nummer)" [The Cagots in France: (End of article in previous number).]. Die Grenzboten: Zeitschrift für Politik, Literatur und Kunst (in German). Vol. 20. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen. 1861. pp. 423–431. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022.

- "Die Cagots in Frankreich" [The Cagots in France]. Die Grenzboten: Zeitschrift für Politik, Literatur und Kunst (in German). Vol. 20. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen. 1861. pp. 393–398. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022.

Obgleich das geseß ihnen gegen ende des vorigen jahrhunderts gleich rechte mit den übrigen bürgern gewährte, ihre sage verbefferte und sie schüßte, ist der fluch, der aus ihnen lastete, doch noch nicht gang gehoben, die berachtung, die sie bedecste, noch nicht gang gewichen und an vielen arten wird ihre unfunft noch als ein schandflect angesehen.

[Although, towards the end of the last century, the seat gave them equal rights with the other citizens, enhanced their speech and shot them, the curse that weighed on them has not yet been lifted, the disrespect that held them has not yet disappeared and in many species, their incompetence is still viewed as a shame.] - Michel (1847), p. 101.

- von Zach (1798), pp. 523–524: "Die letzten und neuesten Nachrichten schreiben sich vom J. 1787 und sind ebenfalls in Ramond's Reisen enthalten. "Ich habe, schreibt dieser Augenzeuge, einige Familien dieser Unglücklichen gesehen. Sie nähern sich unmerklich den Dörfen aus welchen sie verbannt worden. Die Seiten-Thüren, durch welche sie in die Kirchen gingen, werden unnütz. Es vermischt sich endlich ein wenig Mitleid mit der Verachtung und dem Abscheu, welchen sie einflössen. (524) Doch habe ich auch entlegene Hütten angetrossen wo diese Unglücklichen sich 'noch fürchten, vom Vururtheile misshandelt zu werden, und nur vom Mitleiden Besuche erwarten.""

- Hors (1951), pp. 339–341.

- Tucholsky, Kurt (1927). Ein Pyrenäenbuch [A book of the Pyrenees] (in German). Berlin. pp. 97–104. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jolly (2000), p. 207: "Tout le monde se plaît par contre à citer ce qui est donné pour être la dernière manifestation effective du phénomène de ségrégation: le dernier mariage « qui a fait scandale » à Lescun entre une fille de grande famille et un cagot, dans les années 1950."

- "Musée des cagots" [Museum of the Cagots]. Tourisme Midi Pyrenees (in French). Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- "Les cagots à Arreau". Les Hautes-Pyrénées et le village de Loucrup (in French). Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Ravier, Christine (31 August 2021). "Manif anti pass sanitaire en Occitanie: qui sont les "cagots"?" [Anti health pass demonstration in Occitania: who are the "cagots"?]. France 3 (in French). Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- Cantin-Galland, Antoine (25 May 2022). "Le Creusot/Autun/Chagny: France Robert (DLF) veut être « la porte-parole des méprisés du Covid »" [Le Creusot / Autun / Chagny: France Robert (DLF) wants to be "the spokesperson for the despised of the Covid"]. Le Journal de Saône-et-Loire (in French). Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- Izagirre, Ander (12 July 2007). "La palabra hecha piedra" [The word made stone]. El Diario Vasco (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Anne, Coudreuse (2016). "Insultes et théâtre de la Terreur: l'exemple du Jugement dernier des rois (1793) de Pierre-Sylvain Maréchal" [Insults and Theater of Terror: the example of the Last Judgment of Kings (1793) by Pierre-Sylvain Maréchal]. In Turpin, Frédéric (ed.). Les insultes: bilan et perspectives, théorie et actions [Insults: balance sheet and perspectives, theory and actions] (in French). Savoy Mont Blanc University. p. 34. ISBN 978-2-919732-38-8.

La critique du roi d'Espagne permet d'englober tous les Bourbons; la charge est donc très violente: «Il est bien du sang des Bourbons: voyez comme la sottise, la cagoterie et le despotisme sont empreints sur sa face royale.» Signalons qu'il existe un article «Cagot/Cagoterie/Cagotisme» dans le Dictionnaire du Père Duchesne.

[The criticism of the King of Spain makes it possible to encompass all the Bourbons; the charge is therefore very violent: "He is indeed of the blood of the Bourbons: see how stupidity, cagotism and despotism are imprinted on his royal face." Note that there is an article "Cagot/Cagoterie/Cagotisme" in the Dictionary of Father Duchesne.] - Pailleron, Édouard (2010) . Amours Et Haines [Loves and Hates] (in French). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1168078957.

- Novak, Daniel A. (2012). ""Shapeless Deformity": Monstrosity, Visibility, and Racial Masquerade in Thomas Grattan's CAGOT'S HUT (1823)". In Picart, Caroline Joan S.; Browning, John Edgar (eds.). Speaking of Monsters: A Teratological Anthology. Springer. pp. 83–96. doi:10.1057/9781137101495_9. ISBN 978-1-349-29597-5.

- Heine, Heinrich (17 February 2010) . Atta Troll. Translated by Scheffauer, Herman. Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022.

- New York: Scribner, 2024, 123-29, 141-42, 143, 171-72, 222, 329.

- "Monein". Site officiel de l'Office de tourisme de Lacq, Cœur de Béarn (in French). Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Église Saint-Girons de Monein" [Church of Saint-Girons of Monein]. Paroisse Saint-Vincent des Baïses - Monein (in French). Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Fay, Henri Marcel (1910). Champion, H. (ed.). Histoire de la lèpre en France . I. Lépreux et cagots du Sud-Ouest, notes historiques, médicales, philologiques, suivies de documents [History of leprosy in France. I. Lepers and cagots of the South-West, historical, medical, philological notes, followed by documents] (in French). Paris: Librairie ancienne Honoré Champion. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023.

- "Les cagots: un mystère en Béarn" [The cagots: a mystery in Béarn]. Site officiel de l'Office de tourisme de Lacq, Cœur de Béarn (in French). Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Sa construction au XIVème" [Its construction in the 14th century]. Les amis du château de Montaner (in French). Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Álvarez, Jorge (31 October 2019). "Agotes, the mysterious cursed race of the Basque-Navarrese Pyrenees". La Brújula Verde. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Antolini, Paola (1995). Los Agotes. Historia de una exclusión [The Agotes. History of an exclusion] (in Spanish). ISTMO, S.A. ISBN 978-8470902079.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cagots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cagots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Bériac, Françoise (1987). "Une minorité marginale du Sud-Ouest: les cagots" [A marginal minority in the South-West: the cagots]. Histoire, Économie et Société (in French). 6 (1): 17–34. doi:10.3406/hes.1987.1436. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023.

- British Medical Journal (11 May 1912). "Cagots". British Medical Journal. 1 (2680): 1091–1092. JSTOR 25297157.

- Cabarrouy, Jean-Émile (1995). "Les cagots, une race maudite dans le sud de la Gascogne: peut-on dire encore aujourd'hui que leur origin est une énigme?" [The cagots, a cursed race in the south of Gascony: can we still say today that their origin is an enigma?]. Les Cagots, Exclus et maudits des terres du sud [The Cagots, Excluded and cursed from the southern lands] (in French). J. & D. éditions. ISBN 2-84127-043-2.

- del Carmen Aguirre Delclaux, María (2008). Los agotes: El final de una maldición [The Agotes: The End of a Curse] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Madrid: Sílex ediciones [es]. ISBN 978-8477374190.

- Delacampagne, Christian (1983). L'invention du racisme: Antiquité et Moyen-Âge [The invention of racism: Antiquity and the Middle Ages]. Hors collection (in French). Paris: Fayard. doi:10.3917/fayar.delac.1983.01. ISBN 9782213011172. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023.

- Demonet, Marie-Luce (2021). "Rabelais and Language". In Renner, Bernd (ed.). A Companion to François Rabelais. Brill. pp. 402–428. ISBN 978-90-04-46023-2. ISSN 2212-3091.

- Donkin, T.C.; Diez, Friedrich (1864). An Etymological Dictionary of the Romance Languages; chiefly from the German of Friedrich Diez. Williams and Norgate.

- Erroll, Henry (August 1899). "Pariahs of Western Europe". The Cornhill Magazine. Vol. 7, no. 38. London. pp. 243–251. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Garate, Justo (1958). "Los Agotes y La Lepra" [The Agotes and Leprosy]. Boletín de la Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País (in Spanish). 14 (4): 517–530.

- Gaskell, Elizabeth (1855). An Accursed Race. Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023.

- Gébelin, Antoine Court de (1842). Dictionnaire Étymologique, Historique et Anecdotique des Proverbes et des Locutions Proverbiales de la Langue Française [Etymological, Historical and Anecdotal Dictionary of Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases of the French Language] (in French). Paris: P. Bertrand, Libraire-éditeur. pp. 1182–1183.

- Guerreau, Alain ; Guy, Yves (1988). Les cagots du Béarn [The cagots of Béarn] (in French). Minerve.

- Guy, Yves (19 February 1983). "Sur les origines possibles de la ségrégation des Cagots" [On the possible origins of the segregation of cagots] (PDF). Société française d'histoire de la médecine (in French). Centre d'Hémotypologie du C.N.R.S., C.H.U. Purpan et Institut pyrénéen d'Etudes anthropologique: 85–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2021.

- Hansson, Anders (1996). Chinese Outcasts: Discrimination and Emancipation in Late Imperial China. Brill. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-90-04-10596-6.

- Hawkins, Daniel (September 2014). 'Chimeras that degrade humanity': the cagots and discrimination (MA). Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Heng, Geraldine (2022). "Definitions and Representations of Race". In Coles, Kimberley Ann; Kim, Dorothy (eds.). A Cultural History of Race in the Renaissance and Early Modern Age. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-1350067455.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Holy Water Fonts". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Holy Water Fonts". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Hors, Pilar (1951). "Seroantropología e historia de los Agotes" [Sero-Anthropology and history of the Agotes]. Revista Príncipe de Viana (in Spanish). 44–45: 307–343.

- Huici, Rosa María Agudo (1984). "Wentworth Webster: vascófilo, fuerista y etnólogo" [Wentworth Webster: Bascophile, Fuerist and Ethnologist]. Nuevos Extractos de la Rsbap (in Spanish) (A). Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023.

- Jolly, Geneviève (2000). "Les cagots des Pyrénées: une ségrégation attestée, une mobilité mal connue" [The cagots of the Pyrenees: an attested segregation, a poorly known mobility]. Le Monde alpin et rhodanien [fr] (in French). 28 (1–3): 197–222. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023.

- Kessel, Emma Hall (2019). "Without difference, distinction, or separation": Agotes, discrimination, and belonging in Navarre, 1519–1730 (MA). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021.

- Loubès, Gilbert (1995). L'énigme des cagots [The enigma of the cagots] (in French). Bordeaux: Éditions Sud-Ouest [fr]. ISBN 978-2879016580.

- Louis-Lande, Lucien (1878). "Les Cagots et leurs congénères" [Cagots and their congeners]. Revue des deux Mondes (in French). No. 25. pp. 426–450.

- Michel, Francisque Xavier (1847). Histoire Des Races Maudites De La France Et De l'Espagne [History Of The Cursed Races Of France And Spain] (in French). Vol. 1. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022.

- Pérez, Iñaki Sanjuán (21 March 2010). "Los agotes: El pueblo maldito del valle del Baztán" [The Cagots: The cursed town of the Baztán valley]. Suite101.net (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Rivière-Chalan, Vincent Raymond (1 January 1978). La marque infâme des lépreux et des Christians sous l'ancien régime: Des cours des miracles aux cagoteries [The infamous mark of lepers and Christians under the old regime: From miracle courts to cagoteries] (in French). La Pensée Universelle. ASIN B0000E8V67. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023.

- Robb, Graham (2007). The Discovery of France: a historical geography from the Revolution to the First World War. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05973-1. OCLC 124031929.

- Rogozinski, Jacob (2024) . The Logic of Hatred: From Witch Hunts to the Terror. Translated by Razavi, Sephr. Fordham University Press.

- Roussel, Théophile (1893). "Cagots et lépreux" [Cagots and Lepers]. Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris. IVe Série (in French). 4: 148–160. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1893.5421. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023.

- da Silva, Gérard (3 December 2006). "The Cagots of Béarn: The Pariahs of France" (PDF). International Humanist News. International Humanist and Ethical Union. pp. 21–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Thomas, Sean (28 July 2008). "The Last Untouchable in Europe". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- Tuke, D. Hack (1880). "The Cagots". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 9. Wiley: 376–385. doi:10.2307/2841703. JSTOR 2841703. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022.

- Ulysse, Robert (1891). Les signes d'infamie au moyen âge: Juifs, Sarrasins, hérétiques, lépreux, cagots et filles publiques [Signs of infamy in the Middle Ages: Jews, Saracens, heretics, lepers, cagots and public girls] (in French). H. Champion. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Veyrin, Philippe (2011) . "Portraits of Basques — The Gipuzkoans — The Navarrese — The Béarnais — The Gascons — Inner Minorities — Basque Expansion". The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions. Translated by Brown, Andrew. Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada. pp. 75–92. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7.

- von Zach, Franz Xaver (March 1798). "Einige Nachrichten von den Cagots in Frankreich" [Some news of the Cagots in France]. Allgemeine geographische Ephemeriden (in German). 1 (5): 509–524. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021.

- Winkle, Stefan (1997). Kulturgeschichte der Seuchen [Cultural history of epidemics] (in German). Düsseldorf/Zürich: Artemis & Winkler. pp. 39–40. ISBN 3-933366-54-2.

Further reading

- Cordier, E. (1866). "Les Cagots des Pyrénées" [The Cagots of the Pyrenees]. Bulletin de la Société Ramond (in French): 107–119. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022.

- Descazeaux, René (2002). Les Cagots, histoire d'un secret [The Cagots, history of a secret] (in French). Pau: Princi Néguer. ISBN 2846180849.

- Kerexeta Erro, Xabier. "Agote: etnología e historia - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia" [Agote: ethnology and history - Auñamendi Basque Encyclopedia] (in Spanish). Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Marsan, Michel. l'Histoire des cagots à Hagetmau [The history of cagots in Hagetmau] (in French).

- Ricau, Osmin (1999). Histoire des Cagots [History of the Cagots] (in French). Pau: Princi Néguer. ISBN 2905007818.